- October 23 First notes, lasting impressions

- October 23 “Finish what we started”

- October 23 Down to a science

- October 19 Red Cross carving competition

- October 10 All-new boys' volleyball team created

Three Penny Press

Students spend three times longer on homework than average, survey reveals

Sonya Kulkarni and Pallavi Gorantla | Jan 9, 2022

Graphic by Sonya Kulkarni

The National Education Association and the National Parent Teacher Association have suggested that a healthy number of hours that students should be spending can be determined by the “10-minute rule.” This means that each grade level should have a maximum homework time incrementing by 10 minutes depending on their grade level (for instance, ninth-graders would have 90 minutes of homework, 10th-graders should have 100 minutes, and so on).

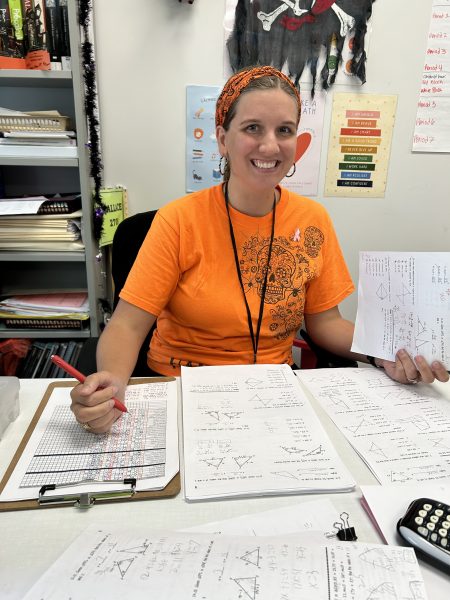

As ‘finals week’ rapidly approaches, students not only devote effort to attaining their desired exam scores but make a last attempt to keep or change the grade they have for semester one by making up homework assignments.

High schoolers reported doing an average of 2.7 hours of homework per weeknight, according to a study by the Washington Post from 2018 to 2020 of over 50,000 individuals. A survey of approximately 200 Bellaire High School students revealed that some students spend over three times this number.

The demographics of this survey included 34 freshmen, 43 sophomores, 54 juniors and 54 seniors on average.

When asked how many hours students spent on homework in a day on average, answers ranged from zero to more than nine with an average of about four hours. In contrast, polled students said that about one hour of homework would constitute a healthy number of hours.

Junior Claire Zhang said she feels academically pressured in her AP schedule, but not necessarily by the classes.

“The class environment in AP classes can feel pressuring because everyone is always working hard and it makes it difficult to keep up sometimes.” Zhang said.

A total of 93 students reported that the minimum grade they would be satisfied with receiving in a class would be an A. This was followed by 81 students, who responded that a B would be the minimum acceptable grade. 19 students responded with a C and four responded with a D.

“I am happy with the classes I take, but sometimes it can be very stressful to try to keep up,” freshman Allyson Nguyen said. “I feel academically pressured to keep an A in my classes.”

Up to 152 students said that grades are extremely important to them, while 32 said they generally are more apathetic about their academic performance.

Last year, nine valedictorians graduated from Bellaire. They each achieved a grade point average of 5.0. HISD has never seen this amount of valedictorians in one school, and as of now there are 14 valedictorians.

“I feel that it does degrade the title of valedictorian because as long as a student knows how to plan their schedule accordingly and make good grades in the classes, then anyone can be valedictorian,” Zhang said.

Bellaire offers classes like physical education and health in the summer. These summer classes allow students to skip the 4.0 class and not put it on their transcript. Some electives also have a 5.0 grade point average like debate.

Close to 200 students were polled about Bellaire having multiple valedictorians. They primarily answered that they were in favor of Bellaire having multiple valedictorians, which has recently attracted significant acclaim .

Senior Katherine Chen is one of the 14 valedictorians graduating this year and said that she views the class of 2022 as having an extraordinary amount of extremely hardworking individuals.

“I think it was expected since freshman year since most of us knew about the others and were just focused on doing our personal best,” Chen said.

Chen said that each valedictorian achieved the honor on their own and deserves it.

“I’m honestly very happy for the other valedictorians and happy that Bellaire is such a good school,” Chen said. “I don’t feel any less special with 13 other valedictorians.”

Nguyen said that having multiple valedictorians shows just how competitive the school is.

“It’s impressive, yet scary to think about competing against my classmates,” Nguyen said.

Offering 30 AP classes and boasting a significant number of merit-based scholars Bellaire can be considered a competitive school.

“I feel academically challenged but not pressured,” Chen said. “Every class I take helps push me beyond my comfort zone but is not too much to handle.”

Students have the opportunity to have off-periods if they’ve met all their credits and are able to maintain a high level of academic performance. But for freshmen like Nguyen, off periods are considered a privilege. Nguyen said she usually has an hour to five hours worth of work everyday.

“Depending on the day, there can be a lot of work, especially with extra curriculars,” Nguyen said. “Although, I am a freshman, so I feel like it’s not as bad in comparison to higher grades.”

According to the survey of Bellaire students, when asked to evaluate their agreement with the statement “students who get better grades tend to be smarter overall than students who get worse grades,” responders largely disagreed.

Zhang said that for students on the cusp of applying to college, it can sometimes be hard to ignore the mental pressure to attain good grades.

“As a junior, it’s really easy to get extremely anxious about your GPA,” Zhang said. “It’s also a very common but toxic practice to determine your self-worth through your grades but I think that we just need to remember that our mental health should also come first. Sometimes, it’s just not the right day for everyone and one test doesn’t determine our smartness.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bellaire High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Down to a science

He’s just a freshman

Coming full circle: Teaching where it all began

HUMANS OF BELLAIRE – Audrey Cheng

Flipping the script

First notes, lasting impressions

“Finish what we started”

Red Cross carving competition

All-new boys’ volleyball team created

Comments (9).

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Anonymous • Jul 16, 2024 at 3:27 pm

didnt realy help

Anonymous • Nov 21, 2023 at 10:32 am

It’s not really helping me understand how much.

josh • May 9, 2023 at 9:58 am

Kassie • May 6, 2022 at 12:29 pm

Im using this for an English report. This is great because on of my sources needed to be from another student. Homework drives me insane. Im glad this is very updated too!!

Kaylee Swaim • Jan 25, 2023 at 9:21 pm

I am also using this for an English report. I have to do an argumentative essay about banning homework in schools and this helps sooo much!

Izzy McAvaney • Mar 15, 2023 at 6:43 pm

I am ALSO using this for an English report on cutting down school days, homework drives me insane!!

luke • Oct 24, 2024 at 9:29 am

I am also using this for an English report. I am making an argumentative essay and this site has helped me complete the essay.

E. Elliott • Apr 25, 2022 at 6:42 pm

I’m from Louisiana and am actually using this for an English Essay thanks for the information it was very informative.

Nabila Wilson • Jan 10, 2022 at 6:56 pm

Interesting with the polls! I didn’t realize about 14 valedictorians, that’s crazy.

- Our Process

WORLDMETRICS.ORG REPORT 2024

Time Spent On Homework Statistics: Insights into Student Workloads

Insights into homework habits reveal academic pressures and stress faced by students. Discover more inside!

Collector: Alexander Eser

Published: 7/23/2024

Statistic 1

- Homework time is often linked to academic achievement, with students who spend more time on homework generally earning higher grades.

Statistic 2

- 40% of students have reported experiencing physical health problems due to the amount of time spent on homework.

Statistic 3

- The homework gap refers to disparities in access to resources needed to complete homework, affecting up to 12 million students in the US.

Statistic 4

- Students in South Korea spend an average of 2.9 hours per day on homework, the highest in the world.

Statistic 5

- Students in Finland, known for its strong education system, have much shorter school days and less homework compared to other countries.

Statistic 6

- Although homework time varies by country, the global average time spent on homework is approximately 4.9 hours per week.

Statistic 7

- The US ranks 17th in the world for the amount of time students spend on homework.

Statistic 8

- Students spend more time on homework in countries with high levels of achievement pressure, such as South Korea and Japan.

Statistic 9

- International comparisons show that time spent on homework is not a direct indicator of academic success, with factors like teaching quality also playing a significant role.

Statistic 10

- 55% of parents are concerned about the amount of homework their children have.

Statistic 11

- 67% of parents report that they help their children with homework, spending an average of 1 hour per week assisting.

Statistic 12

- Students with parents who are highly involved in homework tend to spend more time on assignments.

Statistic 13

- A study found that 1 in 5 students feel overwhelmed by the amount of homework they have.

Statistic 14

- 78% of teachers believe that students are assigned too much homework.

Statistic 15

- The amount of time spent on homework is a common source of stress for students, with 72% reporting feeling stressed about it.

Statistic 16

- 35% of students in the US report having too much homework to juggle with their other commitments.

Statistic 17

- 82% of students admit to cheating on homework assignments at least once.

Statistic 18

- African American students tend to spend more time on homework than their white counterparts, often due to systemic inequalities in education.

Statistic 19

- 65% of students report that the amount of homework they receive is too much.

Statistic 20

- 20% of students report that homework is a major source of family conflict.

Statistic 21

- 32% of students say they don't have enough time for interests outside of school due to the amount of homework they receive.

Statistic 22

- 50% of students believe that homework is not relevant to their learning.

Statistic 23

- In a survey, 72% of students said they multitask while doing homework, which can reduce the effectiveness of study time.

Statistic 24

- 22% of students say that they often feel too tired to do homework after a long school day.

Statistic 25

- Over 30% of students report feeling anxious about not completing homework assignments on time.

Statistic 26

- On average, high school students spend about 6.8 hours per week on homework.

Statistic 27

- Students in grades 6-8 typically spend 1-2 hours on homework per night.

Statistic 28

- 27% of high school students report spending 3 or more hours on homework per night.

Statistic 29

- About 25% of students across all grade levels report spending 10 hours or more on homework per week.

Statistic 30

- The average time spent on homework per week increases as students progress through high school, with seniors spending the most time.

Statistic 31

- 45% of college students report spending 11 hours or more on homework per week.

Statistic 32

- On weekends, high school students spend an average of 3.7 hours on homework.

Statistic 33

- Students in affluent communities tend to have more homework, with high-achieving students spending an average of 17.5 hours per week.

Statistic 34

- The average time spent on homework in the US has been increasing steadily over the past decade.

Statistic 35

- High school students in Japan spend an average of 3 hours per weekday on homework.

Statistic 36

- Students in China have some of the longest school days in the world, spending an average of 3 hours per day on homework.

Statistic 37

- Students in Singapore have some of the highest academic achievement in the world, with an average of 9.4 hours per week spent on homework.

Statistic 38

- Meeting the recommended 10-minute per grade level of daily homework can result in students spending anywhere from 10-120 minutes per day on homework.

Statistic 39

- Homework load tends to peak in the middle school years, with students spending an average of 2-3 hours per day on homework.

Statistic 40

- The National Education Association and the National Parent-Teacher Association recommend a 10-minute per grade level homework guideline.

Our Reports have been cited by:

- • On average, high school students spend about 6.8 hours per week on homework.

- • Students in grades 6-8 typically spend 1-2 hours on homework per night.

- • 27% of high school students report spending 3 or more hours on homework per night.

- • About 25% of students across all grade levels report spending 10 hours or more on homework per week.

- • The average time spent on homework per week increases as students progress through high school, with seniors spending the most time.

- • 45% of college students report spending 11 hours or more on homework per week.

- • Students in South Korea spend an average of 2.9 hours per day on homework, the highest in the world.

- • On weekends, high school students spend an average of 3.7 hours on homework.

- • A study found that 1 in 5 students feel overwhelmed by the amount of homework they have.

- • Students in affluent communities tend to have more homework, with high-achieving students spending an average of 17.5 hours per week.

- • 78% of teachers believe that students are assigned too much homework.

- • The amount of time spent on homework is a common source of stress for students, with 72% reporting feeling stressed about it.

- • 35% of students in the US report having too much homework to juggle with their other commitments.

- • 55% of parents are concerned about the amount of homework their children have.

- • The average time spent on homework in the US has been increasing steadily over the past decade.

Time flies when youre avoiding homework like the plague, but for many students, hitting the books is just part of the weekly grind. According to recent statistics, high school students are putting in an average of 6.8 hours per week on homework, with seniors leading the charge. But dont be fooled by the seemingly manageable numbers – a whopping 27% of high schoolers admit to clocking in 3 or more hours per night, while 45% of college students are burning the midnight oil for 11 hours or more weekly. As students around the world juggle textbooks and stress, from South Koreas daily homework marathons to Finlands more relaxed approach, one thing remains clear: the homework struggle is real, folks.

Impact of homework on student well-being

Interpretation.

In the ever-evolving saga of student life, the correlation between time spent on homework and academic success continues to reign supreme, like an old-school king holding court in a digital age. However, lurking beneath this kingdom of textbooks and highlighters lies a dark underbelly of physical woes, with 40% of students falling victim to the treacherous grip of health problems brought on by the relentless pursuit of knowledge through homework. As if that wasn't enough drama for one scholarly epic, the homework gap emerges as a formidable foe, casting its shadow over 12 million students in the US who are left grappling with disparities in essential resources, painting a poignant picture of inequality in the whimsical world of academic adventures.

International comparisons of homework time

In the grand race of education, it seems each country has its own strategy when it comes to the homework hustle. South Korea is sprinting ahead with an impressive 2.9 hours per day of homework, while Finland takes a leisurely stroll with shorter school days and less homework, confidently striding on its strong education system reputation. Meanwhile, the global average of 4.9 hours per week keeps everyone in check, showing that sometimes slow and steady wins the race. The US, cruising in at 17th place, seems content with its homework pace. As the pressure mounts in countries like South Korea and Japan, it's clear that academic success is not just a marathon of homework hours but a complex relay of teaching quality and student support. So, whether you're zooming through assignments or taking a scenic route, remember that the true finish line is where knowledge meets understanding, not just where your homework stack ends.

Parental involvement in homework

In a world where parental involvement in homework is both praised and feared, these statistics reveal a tangled web of concern and assistance. With over half of parents worrying about the homework load, it seems that the battle between academics and family time is very much present in households. And yet, amidst the chaos, there is a bright spot of unity as two-thirds of parents roll up their sleeves and dive into the sea of equations and essays, clocking in an average of an hour per week. It's a delicate dance where parental support can either lighten the load or inadvertently add weight to the backpacks of the diligent scholars of tomorrow.

Student perceptions and feelings about homework

Amidst the homework chaos, these statistics paint a picture of a system teetering on the edge of overload. From overwhelmed students to burdened teachers, the common thread of stress weaves through the fabric of education. As the scales tip toward exhaustion and cheating becomes a tempting shortcut, it's clear that the homework battle is taking a toll. While some juggle homework with a deft hand, others find themselves drowning in assignments that seem to have little relevance. As students strive to balance academics with personal lives, the shadow of systemic inequalities looms large, highlighting the stark disparities in educational experiences. In this swirling maelstrom of deadlines and conflicts, perhaps it's time to reconsider the purpose and impact of homework, lest we lose sight of the true essence of learning amidst the chaos of completion.

Time spent on homework by grade level

In the ongoing academic battle of brains versus textbooks, the battlefield of homework is where the skirmish rages on. From the skirmish of middle school to the all-out assault of high school, students worldwide are clocking in impressive hours at the academic coalface. As the numbers stack up, it’s clear that the homework war knows no bounds, with students from all corners of the globe putting in the overtime. But as they juggle assignments and essays, one thing remains constant: the struggle is real, the workload is heavy, and the battle cry for education echoes across continents.

livescience.com

blog.act.org

journalistsresource.org

collegexpress.com

pewresearch.org

nytimes.com

parenting.com

brookings.edu

washingtonpost.com

psychologytoday.com

civicscience.com

nces.ed.gov

eurasiareview.com

straitstimes.com

understood.org

kidshealth.org

nimh.nih.gov

ourworldindata.org

scholastic.com

journals.sagepub.com

edutopia.org

nbcnews.com

sleepfoundation.org

oecd-forum.org

11 Surprising Homework Statistics, Facts & Data

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

The age-old question of whether homework is good or bad for students is unanswerable because there are so many “ it depends ” factors.

For example, it depends on the age of the child, the type of homework being assigned, and even the child’s needs.

There are also many conflicting reports on whether homework is good or bad. This is a topic that largely relies on data interpretation for the researcher to come to their conclusions.

To cut through some of the fog, below I’ve outlined some great homework statistics that can help us understand the effects of homework on children.

Homework Statistics List

1. 45% of parents think homework is too easy for their children.

A study by the Center for American Progress found that parents are almost twice as likely to believe their children’s homework is too easy than to disagree with that statement.

Here are the figures for math homework:

- 46% of parents think their child’s math homework is too easy.

- 25% of parents think their child’s math homework is not too easy.

- 29% of parents offered no opinion.

Here are the figures for language arts homework:

- 44% of parents think their child’s language arts homework is too easy.

- 28% of parents think their child’s language arts homework is not too easy.

- 28% of parents offered no opinion.

These findings are based on online surveys of 372 parents of school-aged children conducted in 2018.

2. 93% of Fourth Grade Children Worldwide are Assigned Homework

The prestigious worldwide math assessment Trends in International Maths and Science Study (TIMSS) took a survey of worldwide homework trends in 2007. Their study concluded that 93% of fourth-grade children are regularly assigned homework, while just 7% never or rarely have homework assigned.

3. 17% of Teens Regularly Miss Homework due to Lack of High-Speed Internet Access

A 2018 Pew Research poll of 743 US teens found that 17%, or almost 2 in every 5 students, regularly struggled to complete homework because they didn’t have reliable access to the internet.

This figure rose to 25% of Black American teens and 24% of teens whose families have an income of less than $30,000 per year.

4. Parents Spend 6.7 Hours Per Week on their Children’s Homework

A 2018 study of 27,500 parents around the world found that the average amount of time parents spend on homework with their child is 6.7 hours per week. Furthermore, 25% of parents spend more than 7 hours per week on their child’s homework.

American parents spend slightly below average at 6.2 hours per week, while Indian parents spend 12 hours per week and Japanese parents spend 2.6 hours per week.

5. Students in High-Performing High Schools Spend on Average 3.1 Hours per night Doing Homework

A study by Galloway, Conner & Pope (2013) conducted a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California.

Across these high-performing schools, students self-reported that they did 3.1 hours per night of homework.

Graduates from those schools also ended up going on to college 93% of the time.

6. One to Two Hours is the Optimal Duration for Homework

A 2012 peer-reviewed study in the High School Journal found that students who conducted between one and two hours achieved higher results in tests than any other group.

However, the authors were quick to highlight that this “t is an oversimplification of a much more complex problem.” I’m inclined to agree. The greater variable is likely the quality of the homework than time spent on it.

Nevertheless, one result was unequivocal: that some homework is better than none at all : “students who complete any amount of homework earn higher test scores than their peers who do not complete homework.”

7. 74% of Teens cite Homework as a Source of Stress

A study by the Better Sleep Council found that homework is a source of stress for 74% of students. Only school grades, at 75%, rated higher in the study.

That figure rises for girls, with 80% of girls citing homework as a source of stress.

Similarly, the study by Galloway, Conner & Pope (2013) found that 56% of students cite homework as a “primary stressor” in their lives.

8. US Teens Spend more than 15 Hours per Week on Homework

The same study by the Better Sleep Council also found that US teens spend over 2 hours per school night on homework, and overall this added up to over 15 hours per week.

Surprisingly, 4% of US teens say they do more than 6 hours of homework per night. That’s almost as much homework as there are hours in the school day.

The only activity that teens self-reported as doing more than homework was engaging in electronics, which included using phones, playing video games, and watching TV.

9. The 10-Minute Rule

The National Education Association (USA) endorses the concept of doing 10 minutes of homework per night per grade.

For example, if you are in 3rd grade, you should do 30 minutes of homework per night. If you are in 4th grade, you should do 40 minutes of homework per night.

However, this ‘rule’ appears not to be based in sound research. Nevertheless, it is true that homework benefits (no matter the quality of the homework) will likely wane after 2 hours (120 minutes) per night, which would be the NEA guidelines’ peak in grade 12.

10. 21.9% of Parents are Too Busy for their Children’s Homework

An online poll of nearly 300 parents found that 21.9% are too busy to review their children’s homework. On top of this, 31.6% of parents do not look at their children’s homework because their children do not want their help. For these parents, their children’s unwillingness to accept their support is a key source of frustration.

11. 46.5% of Parents find Homework too Hard

The same online poll of parents of children from grades 1 to 12 also found that many parents struggle to help their children with homework because parents find it confusing themselves. Unfortunately, the study did not ask the age of the students so more data is required here to get a full picture of the issue.

Get a Pdf of this article for class

Enjoy subscriber-only access to this article’s pdf

Interpreting the Data

Unfortunately, homework is one of those topics that can be interpreted by different people pursuing differing agendas. All studies of homework have a wide range of variables, such as:

- What age were the children in the study?

- What was the homework they were assigned?

- What tools were available to them?

- What were the cultural attitudes to homework and how did they impact the study?

- Is the study replicable?

The more questions we ask about the data, the more we realize that it’s hard to come to firm conclusions about the pros and cons of homework .

Furthermore, questions about the opportunity cost of homework remain. Even if homework is good for children’s test scores, is it worthwhile if the children consequently do less exercise or experience more stress?

Thus, this ends up becoming a largely qualitative exercise. If parents and teachers zoom in on an individual child’s needs, they’ll be able to more effectively understand how much homework a child needs as well as the type of homework they should be assigned.

Related: Funny Homework Excuses

The debate over whether homework should be banned will not be resolved with these homework statistics. But, these facts and figures can help you to pursue a position in a school debate on the topic – and with that, I hope your debate goes well and you develop some great debating skills!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How Much Homework Is Too Much for Our Teens?

Here's what educators and parents can do to help kids find the right balance between school and home.

Does Your Teen Have Too Much Homework?

Today’s teens are under a lot of pressure.

They're under pressure to succeed, to win, to be the best and to get into the top colleges. With so much pressure, is it any wonder today’s youth report being under as much stress as their parents? In fact, during the school year, teens say they experience stress levels higher than those reported by adults, according to a previous American Psychological Association "Stress in America" survey.

Odds are if you ask a teen what's got them so worked up, the subject of school will come up. School can cause a lot of stress, which can lead to other serious problems, like sleep deprivation . According to the National Sleep Foundation, teens need between eight and 10 hours of sleep each night, but only 15 percent are even getting close to that amount. During the school week, most teens only get about six hours of zzz’s a night, and some of that sleep deficit may be attributed to homework.

When it comes to school, many adults would rather not trade places with a teen. Think about it. They get up at the crack of dawn and get on the bus when it’s pitch dark outside. They put in a full day sitting in hours of classes (sometimes four to seven different classes daily), only to get more work dumped on them to do at home. To top it off, many kids have after-school obligations, such as extracurricular activities including clubs and sports , and some have to work. After a long day, they finally get home to do even more work – schoolwork.

[Read: What Parents Should Know About Teen Depression .]

Homework is not only a source of stress for students, but it can also be a hassle for parents. If you are the parent of a kid who strives to be “perfect," then you know all too well how much time your child spends making sure every bit of homework is complete, even if it means pulling an all-nighter. On the flip side, if you’re the parent of a child who decided that school ends when the last bell rings, then you know how exhausting that homework tug-of-war can be. And heaven forbid if you’re that parent who is at their wit's end because your child excels on tests and quizzes but fails to turn in assignments. The woes of academics can go well beyond the confines of the school building and right into the home.

This is the time of year when many students and parents feel the burden of the academic load. Following spring break, many schools across the nation head into the final stretch of the year. As a result, some teachers increase the amount of homework they give. The assignments aren’t punishment, although to students and parents who are having to constantly stay on top of their kids' schoolwork, they can sure seem that way.

From a teacher’s perspective, the assignments are meant to help students better understand the course content and prepare for upcoming exams. Some schools have state-mandated end of grade or final tests. In those states these tests can account for 20 percent of a student’s final grade. So teachers want to make sure that they cover the entire curriculum before that exam. Aside from state-mandated tests, some high school students are enrolled in advanced placement or international baccalaureate college-level courses that have final tests given a month or more before the end of the term. In order to cover all of the content, teachers must maintain an accelerated pace. All of this means more out of class assignments.

Given the challenges kids face, there are a few questions parents and educators should consider:

Is homework necessary?

Many teens may give a quick "no" to this question, but the verdict is still out. Research supports both sides of the argument. Personally, I would say, yes, some homework is necessary, but it must be purposeful. If it’s busy work, then it’s a waste of time. Homework should be a supplemental teaching tool. Too often, some youth go home completely lost as they haven’t grasped concepts covered in class and they may become frustrated and overwhelmed.

For a parent who has been in this situation, you know how frustrating this can be, especially if it’s a subject that you haven’t encountered in a while. Homework can serve a purpose such as improving grades, increasing test scores and instilling a good work ethic. Purposeful homework can come in the form of individualizing assignments based on students’ needs or helping students practice newly acquired skills.

Homework should not be used to extend class time to cover more material. If your child is constantly coming home having to learn the material before doing the assignments, then it’s time to contact the teacher and set up a conference. Listen when kids express their concerns (like if they say they're expected to know concepts not taught in class) as they will provide clues about what’s happening or not happening in the classroom. Plus, getting to the root of the problem can help with keeping the peace at home too, as an irritable and grumpy teen can disrupt harmonious family dynamics .

[Read: What Makes Teens 'Most Likely to Succeed?' ]

How much is too much?

According to the National PTA and the National Education Association, students should only be doing about 10 minutes of homework per night per grade level. But teens are doing a lot more than that, according to a poll of high school students by the organization Statistic Brain . In that poll teens reported spending, on average, more than three hours on homework each school night, with 11th graders spending more time on homework than any other grade level. By contrast, some polls have shown that U.S. high school students report doing about seven hours of homework per week.

Much of a student's workload boils down to the courses they take (such as advanced or college prep classes), the teaching philosophy of educators and the student’s commitment to doing the work. Regardless, research has shown that doing more than two hours of homework per night does not benefit high school students. Having lots of homework to do every day makes it difficult for teens to have any downtime , let alone family time .

How do we respond to students' needs?

As an educator and parent, I can honestly say that oftentimes there is a mismatch in what teachers perceive as only taking 15 minutes and what really takes 45 minutes to complete. If you too find this to be the case, then reach out to your child's teacher and find out why the assignments are taking longer than anticipated for your child to complete.

Also, ask the teacher about whether faculty communicate regularly with one another about large upcoming assignments. Whether it’s setting up a shared school-wide assignment calendar or collaborating across curriculums during faculty meetings, educators need to discuss upcoming tests and projects, so students don’t end up with lots of assignments all competing for their attention and time at once. Inevitably, a student is going to get slammed occasionally, but if they have good rapport with their teachers, they will feel comfortable enough to reach out and see if alternative options are available. And as a parent, you can encourage your kid to have that dialogue with the teacher.

Often teens would rather blend into the class than stand out. That’s unfortunate because research has shown time and time again that positive teacher-student relationships are strong predictors of student engagement and achievement. By and large, most teachers appreciate students advocating for themselves and will go the extra mile to help them out.

Can there be a balance between home and school?

Students can strike a balance between school and home, but parents will have to help them find it. They need your guidance to learn how to better manage their time, get organized and prioritize tasks, which are all important life skills. Equally important is developing good study habits. Some students may need tutoring or coaching to help them learn new material or how to take notes and study. Also, don’t forget the importance of parent-teacher communication. Most educators want nothing more than for their students to succeed in their courses.

Learning should be fun, not mundane and cumbersome. Homework should only be given if its purposeful and in moderation. Equally important to homework is engaging in activities, socializing with friends and spending time with the family.

[See: 10 Concerns Parents Have About Their Kids' Health .]

Most adults don’t work a full-time job and then go home and do three more hours of work, and neither should your child. It's not easy learning to balance everything, especially if you're a teen. If your child is spending several hours on homework each night, don't hesitate to reach out to teachers and, if need be, school officials. Collectively, we can all work together to help our children de-stress and find the right balance between school and home.

12 Questions You Should Ask Your Kids at Dinner

Tags: parenting , family , family health , teens , education , high school , stress

Most Popular

Best Hospitals

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health ».

Your Health

A guide to nutrition and wellness from the health team at U.S. News & World Report.

You May Also Like

Moderating pandemic news consumption.

Victor G. Carrion, M.D. June 8, 2020

Helping Young People Gain Resilience

Nancy Willard May 18, 2020

Keep Kids on Track With Reading During the Pandemic

Ashley Johnson and Tom Dillon May 14, 2020

Pandemic and Summer Education

Nancy Willard May 12, 2020

Trauma and Childhood Regression

Dr. Gail Saltz May 8, 2020

The Sandwich Generation and the Pandemic

Laurie Wolk May 6, 2020

Adapting to an Evolving Pandemic

Laurie Wolk May 1, 2020

Picky Eating During Quarantine

Jill Castle May 1, 2020

Baby Care During the Pandemic

Dr. Natasha Burgert April 29, 2020

Co-Parenting During the Pandemic

Ron Deal April 24, 2020

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School’s In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

The way U.S. teens spend their time is changing, but differences between boys and girls persist

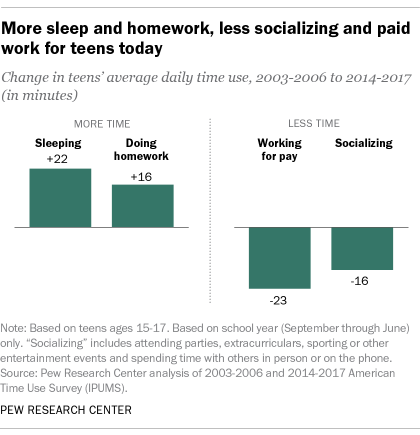

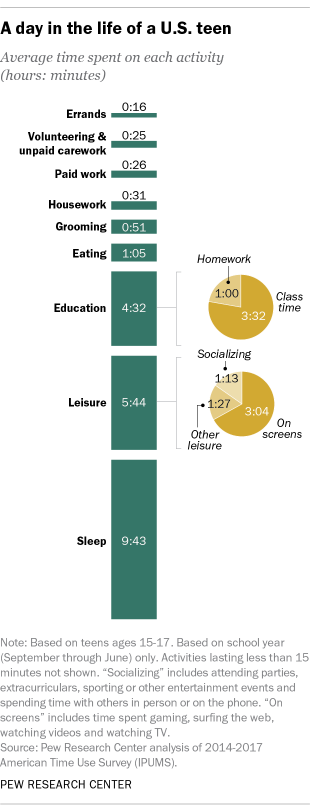

Teens today are spending their time differently than they did a decade ago. They’re devoting more time to sleep and homework, and less time to paid work and socializing. But what has not changed are the differences between teen boys and girls in time spent on leisure, grooming, homework, housework and errands, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Overall, teens (ages 15 to 17) spend an hour a day, on average, doing homework during the school year, up from 44 minutes a day about a decade ago and 30 minutes in the mid-1990s.

Teens are also getting more shut-eye than they did in the past. They are clocking an average of over nine and a half hours of sleep a night, an increase of 22 minutes compared with teens a decade ago and almost an hour more than those in the mid-1990s. Sleep patterns fluctuate quite a bit – on weekends, teens average about 11 hours, while on weekdays they typically get just over nine hours a night. (While these findings are derived from time diaries in which respondents record the amount of time they slept on the prior night, results from other types of surveys suggest teens are getting fewer hours of sleep .)

Teens now enjoy more than five and a half hours of leisure a day (5 hours, 44 minutes). The biggest chunk of teens’ daily leisure time is spent on screens: 3 hours and 4 minutes on average. This figure, which can include time spent gaming, surfing the web, watching videos and watching TV, has held steady over the past decade. On weekends, screen time increases to almost four hours a day (3 hours, 53 minutes), and on weekdays teens are spending 2 hours and 44 minutes on screens.

Time spent playing sports has held steady at around 45 minutes, as has the time teens spend in other types of leisure such as shopping for clothes, listening to music and reading for pleasure.

Time spent by teens in other leisure activities has declined. Over the past decade, the time spent socializing – including attending parties, extracurriculars, sporting or other entertainment events as well as spending time with others in person or on the phone – has dropped by 16 minutes, to 1 hour and 13 minutes a day.

Teens also are spending less time on paid work during the school year than their predecessors: 26 minutes a day, on average, compared with 49 minutes about a decade ago and 57 minutes in the mid-1990s. Much of this decline reflects the fact that teens are less likely to work today than in the past; among employed teens, the amount of time spent working is not much different now than it was around 2005.

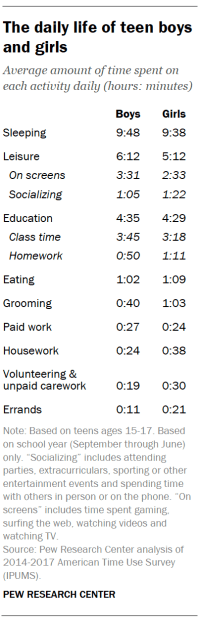

While the way teens overall spend their time has changed in a number of ways, persistent gender differences in time use remain. Teen boys are spending an average of about six hours a day in leisure time, compared with roughly five hours a day for girls – driven largely by the fact that boys are spending about an hour (58 minutes) more a day than girls engaged in screen time. Boys also spend more time playing sports: 59 minutes vs. 33 minutes for girls.

On the flip side, girls spend 10 more minutes a day, on average, shopping for items such as clothes or going to the mall (15 minutes vs. 5 minutes).

Teen girls also spend more time than boys on grooming activities, such as bathing, getting dressed, getting haircuts, and other activities related to their hygiene and appearance. Girls spend an average of about an hour a day on these types of tasks (1 hour, 3 minutes); boys spend 40 minutes on them.

Girls also devote 21 more minutes a day to homework than boys do – 71 minutes vs. 50 minutes, on average, during the school year. This pattern has held steady over the past decade, as the amount of time spent on homework has risen equally for boys and girls.

When it comes to the amount of time spent on housework, the differences between boys and girls reflect gender dynamics that are also evident among adults . Teenage girls spend 38 minutes a day, on average, helping around the house during the school year, compared with 24 minutes a day for boys. The bulk of this gap is driven by the fact that girls spend more than twice as much time cleaning up and preparing food as boys do (29 minutes vs. 12 minutes). There are not significant differences in the amount of time boys and girls spend on home maintenance and lawn care.

Girls also spend more time running errands, such as shopping for groceries (21 minutes vs. 11 minutes for boys).

In addition to these differences in how they spend their time, the way boys and girls feel about their day also differs in some key ways. A new survey by Pew Research Center of teens ages 13 to 17 finds that 36% of girls say they feel tense or nervous about their day every or almost every day; 23% of boys say the same. At the same time, girls are more likely than boys to say they get excited daily or almost daily by something they study in school (33% vs. 21%). And while similar shares of boys and girls say they feel a lot of pressure to get good grades, be involved in extracurricular activities or fit in socially, girls are more likely than boys to say they face a lot of pressure to look good (35% vs. 23%).

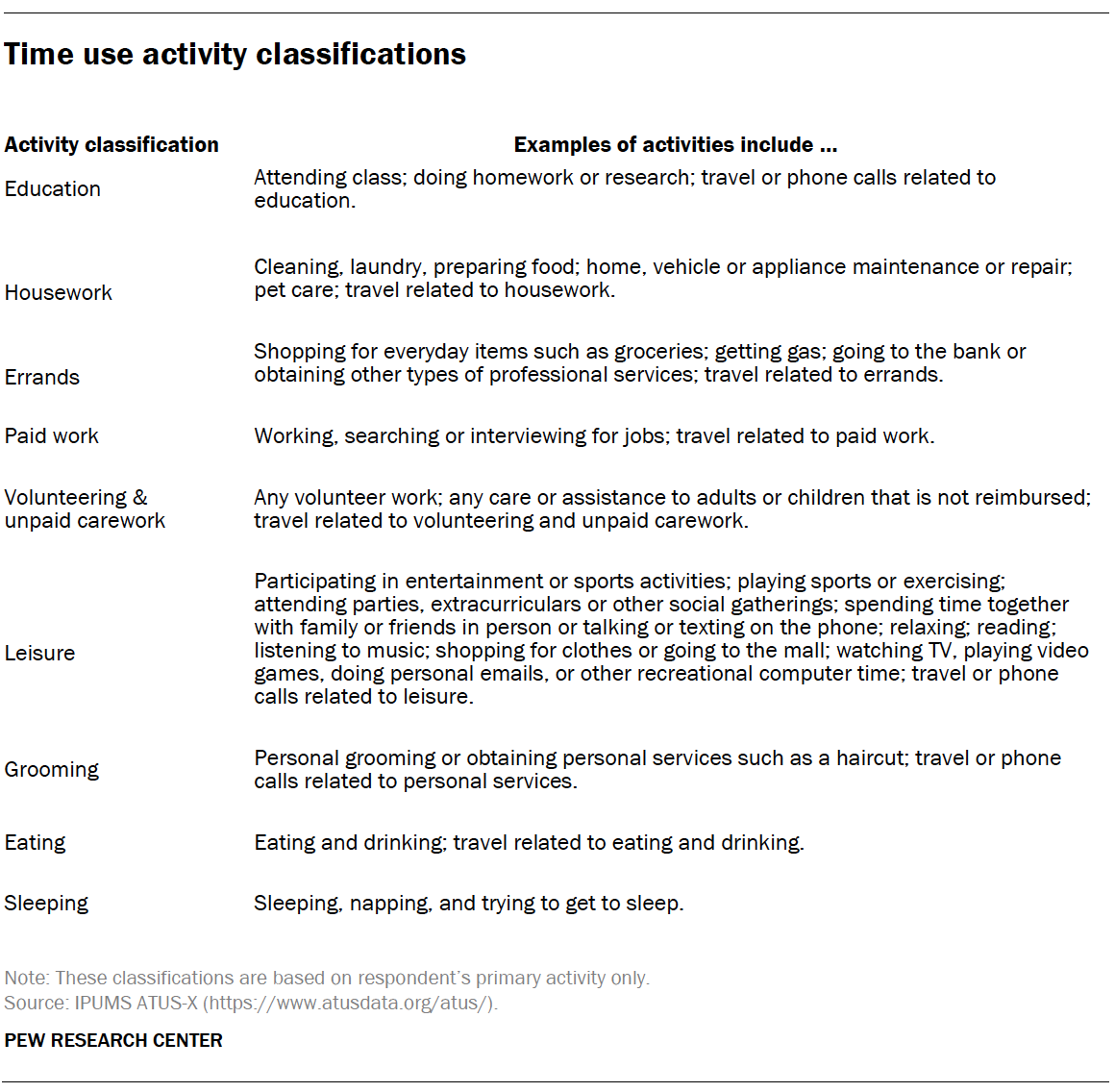

This analysis is based primarily on time diary data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which has been sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and annually conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau since 2003. The ATUS produces a nationally representative sample of respondents, drawn from the Current Population Survey.

Most of the analyses are based on respondents in the 2003-2006 and the 2014-2017 ATUS samples (referred to in the text as “2005” and “2015”). Data regarding time use in the mid-1990s is based on 1992-1994 data from the American Heritage Time Use Survey (AHTUS). For all time points, multiple years of data were combined in order to increase sample size. Because time use among teens can vary so much between the summer and the school year, only data for September through June are used for these analyses. Although focused on the school year, the data also reflect time use during school holidays, such as spring break.

These time diaries track in detail how Americans spend their time, focusing on each respondent’s primary activity (i.e., the main thing they were doing) sequentially for the prior day, including the start and end times for each activity.

All data were accessed via the ATUS-X website made available through IPUMS .

- Age & Generations

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Generation Z

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

Gretchen Livingston is a former senior researcher focusing on fertility and family demographics at Pew Research Center .

5 facts about student loans

U.s. adults under 30 have different foreign policy priorities than older adults, across asia, respect for elders is seen as necessary to be ‘truly’ buddhist, teens and video games today, as biden and trump seek reelection, who are the oldest – and youngest – current world leaders, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Analyzing ‘the homework gap’ among high school students

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, michael hansen and michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies diana quintero diana quintero former senior research analyst, brown center on education policy - the brookings institution, ph.d. student - vanderbilt university.

August 10, 2017

Researchers have struggled for decades to identify a causal, or even correlational, relationship between time spent in school and improved learning outcomes for students. Some studies have focused on the length of a school year while others have focused on hours in a day and others on hours in the week .

In this blog post, we will look at time spent outside of school–specifically time spent doing homework–among different racial and socio-economic groups. We will use data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) to shed light on those differences and then attempt to explain those gaps, using ATUS data and other evidence.

What we know about out-of-school time

Measuring the relationship between out-of-school time and outcomes like test scores can be difficult. Researchers are primarily confounded by an inability to determine what compels students to choose homework during their time off over other activities. Are those who spend more time on homework just extra motivated? Or are they struggling students who need to work harder to keep up? What role do social expectations from parents or peers play?

Previous studies have examined the impact of this outside time use on educational outcomes for students. A 2007 study using data from Berea College in Kentucky identified a causal relationship between hours spent studying and a student’s academic performance through an interesting measure. The researchers took advantage of randomly assigned college roommates, paying attention to those who came to campus with a video game console in tow. They hypothesized students randomly assigned to a roommate without a video game console would study more, since all other factors remained equal. That hypothesis held up, and that group also received significantly higher grades, demonstrating the causal relationship.

Other research has relied on data collected through the American Time Use Survey, a study of how Americans spend their time, and shown the existence of a gender gap and a parental education gap in homework time. Other studies have looked at the relationship between holding a job and student’s time use in discretionary activities , like sleep, media consumption, and time spent on homework. We are curious about out-of-school differences in homework time by race and income.

Descriptive statistics of time use

We began with a general sample of 2,575 full-time high school students between the ages of 15 and 18 from the ATUS, restricting the sample to their answers about time spent on homework during weekdays and school months (September to May). Among all high school students surveyed (those that reported completing their homework and those that did not), the time allocated to complete homework amounted to less than an hour per day, despite the fact that high school teachers report they assign an average of 3.5 hours of homework per day.

To explore racial or income-based differences, in Figure 1, we plot the minutes that students reporting spending on homework separately by their racial/ethnic group and family income. We observed a time gap between racial groups, with Asian students spending the most time on homework (nearly two hours a day). Similarly, we observe a time gap by the students’ family income.

We can also use ATUS data to isolate when students do homework by race and by income. In Figure 2, we plot the percentage of high school students in each racial and income group doing homework by the time of day. Percentages remain low during the school day and then expectedly increase when students get home, with more Asian students doing more homework and working later into the night than other racial groups. Low-income students reported doing less homework per hour than their non-low-income peers.

Initial attempts to explain the homework gap

We hypothesized that these racial and income-based time gaps could potentially be explained by other factors, like work, time spent caring for others, and parental education. We tested these hypotheses by separating groups based on particular characteristics and comparing the average number of minutes per day spent on homework amongst the comparison groups.

Students who work predictably reported spending less time on educational activities, so if working disproportionately affected particular racial or income groups, then work could help explain the time gap. Students who worked allocated on average 20 minutes less for homework than their counterparts who did not work. Though low-income students worked more hours than their peers, they largely maintained a similar level of homework time by reducing their leisure or extracurricular activities. Therefore, the time gap on homework changed only slightly with the inclusion of work as a factor.

We also incorporated time spent taking care of others in the household. Though a greater percentage of low-income students take care of other household members, we found that this does not have a statistically significant effect on homework because students reduce leisure, rather than homework, in an attempt to help their families. Therefore, this variable again does not explain the time gaps.

Finally, we considered parental education, since parents with more education have been shown to encourage their children to value school more and have the resources to ensure homework is completed more easily. Our analysis showed students with at least one parent with any post-secondary degree (associate or above) reported spending more time on homework than their counterparts whose parents do not hold a degree; however, gaps by race still existed, even holding parental education constant. Turning to income levels, we found that parental education is more correlated with homework time among low-income students, reducing the time gap between income groups to only eight minutes.

Societal explanations

Our analysis of ATUS could not fully explain this gap in time spent on homework, especially among racial groups. Instead, we believe that viewing homework as an outcome of the culture of the school and the expectations of teachers, rather than an outcome of a student’s effort, may provide some reasons for its persistence.

Many studies, including recent research , have shown that teachers perceive students of color as academically inferior to their white peers. A 2016 study by Seth Gershenson et al. showed that this expectations gap can also depend on the race of the teacher. In a country where minority students make up nearly half of all public school students, yet minority teachers comprise just 18 percent of the teacher workforce, these differences in expectations matter.

Students of color are also less likely to attend high schools that offer advanced courses (including Advanced Placement courses) that would likely assign more homework, and thus access to rigorous courses may partially explain the gaps as well.

Research shows a similar, if less well-documented, gap by income, with teachers reporting lower expectations and dimmer futures for their low-income students. Low-income students and students of color may be assigned less homework based on lower expectations for their success, thus preventing them from learning as much and creating a self-fulfilling prophecy .

In conclusion, these analyses of time use revealed a substantial gap in homework by race and by income group that could not be entirely explained by work, taking care of others, or parental education. Additionally, differences in educational achievement, especially as measured on standardized tests, have been well-documented by race and by income . These gaps deserve our attention, but we should be wary of blaming disadvantaged groups. Time use is an outcome reflecting multiple factors, not simply motivation, and a greater understanding of that should help raise expectations–and therefore, educational achievement–all around.

Sarah Novicoff contributed to this post.

Related Content

Michael Hansen, Diana Quintero

October 5, 2016

Sarah Novicoff, Matthew A. Kraft

November 15, 2022

September 10, 2015

K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Catherine Mata

October 21, 2024

Dick Startz

October 17, 2024

Mary Burns, Rebecca Winthrop, Michael Trucano, Natasha Luther

October 15, 2024

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Your content has been saved!

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

Students Spend More Time on Homework but Teachers Say It's Worth It

Time spent on homework has increased in recent years, but educators say that's because the assignments have also changed.

Students Spending More Time on Homework

iStockphoto

High school students get assigned up to 17.5 hours of homework per week, according to a survey of 1,000 teachers.

Although students nowadays are spending significantly more time on homework assignments – sometimes up to 17.5 hours each week – the type and quality of the assignments have changed to better capture critical thinking skills and higher levels of learning, according to a recent survey of teachers conducted by the University of Phoenix College of Education.

The survey of 1,000 K-12 teachers found, among other things, that high school teachers on average assign about 3.5 hours of homework each week. For high school students who typically have five classes with different teachers, that could mean as much as 17.5 hours each week. By comparison, the survey found middle school teachers assign about 3.2 hours of homework each week and kindergarten through fifth grade teachers assign about 2.9 hours each week.

[ READ : Standardized Testing Debate Should Focus on Local School Districts, Report Says ]

By comparison, a 2011 study from the National Center for Education Statistics found high school students reported spending an average of 6.8 hours of homework per week, while a 1994 report from the National Center for Education Statistics – reviewing trends in data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress – found 39 percent of 17-year-olds said they did at least one hour of homework each day.

"What has changed is not necessarily the magic number of how many hours they’re doing per night, but it’s the quality of the homework," says Ashley Norris, assistant dean of the university's college of education. Part of that shift in recent years, she says, may come from more schools implementing the Common Core State Standards, which are intended to put more of an emphasis on critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

"You see a change from teachers … giving, really, busy work … to where they’re actually creating long-term projects that students have to manage outside of the classroom, or reading, where they read and come back into the classroom and share their findings," Norris says. "It's not just about rote memorization, because we know that doesn't stick."

For younger students, having more meaningful homework assignments can help build time-management skills, as well as enhance parent-child interaction, Norris says. But the bigger connection for high school students, she says, is doing assignments outside of the classroom that get them interested in a career path.

[ MORE : How Virtual Games Can Help Struggling Students Learn ]

Moving forward, as more schools dive into more time-consuming – but Norris says more meaningful – assignments, there may be a greater shift in the number of schools utilizing the "flipped classroom" method, in which students watch a lesson or lecture at home online, and bring their questions to the classroom to work with their peers while the teacher is present to help facilitate any problems that arise.

"This is already happening in the classrooms. And I think that idea, this whole idea where homework is this applied learning that goes outside the boundaries of a classroom – what can we use that actual class time for?" Norris says "To come back and collaborate on learning, learn from each other, maybe critique our own [work] and share those experiences."

Join the Conversation

Tags: K-12 education , education , Common Core , teachers

America 2024

U.S. News Decision Points

Your trusted source for the latest news delivered weekdays from the team at U.S. News and World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

The Best Cartoons on Donald Trump

Oct. 24, 2024, at 11:50 a.m.

Joe Biden Behind The Scenes

Oct. 15, 2024

The GOP’s Cases Against the ‘24 Vote

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton Oct. 24, 2024

He Said, She Said: Flagging Fascism

Laura Mannweiler Oct. 24, 2024

The Military Leaders Against Trump

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton Oct. 23, 2024

Has Trump Hit the Wall?

Laura Mannweiler Oct. 23, 2024

Harris’ Closing Media Blitz

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder Oct. 23, 2024

Fed: Economy Steady, Job Market Balanced

Tim Smart Oct. 23, 2024

He Said, She Said: Election Mythmaking

How Much Homework Do American Kids Do?

Various factors, from the race of the student to the number of years a teacher has been in the classroom, affect a child's homework load.

![how many hours do students spend on homework a day [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_Post.jpg)

In his Atlantic essay , Karl Taro Greenfeld laments his 13-year-old daughter's heavy homework load. As an eighth grader at a New York middle school, Greenfeld’s daughter averaged about three hours of homework per night and adopted mantras like “memorization, not rationalization” to help her get it all done. Tales of the homework-burdened American student have become common, but are these stories the exception or the rule?

A 2007 Metlife study found that 45 percent of students in grades three to 12 spend more than an hour a night doing homework, including the six percent of students who report spending more than three hours a night on their homework. In the 2002-2003 school year, a study out of the University of Michigan found that American students ages six through 17 spent three hours and 38 minutes per week doing homework.

A range of factors plays into how much homework each individual student gets:

Older students do more homework than their younger counterparts.

This one is fairly obvious: The National Education Association recommends that homework time increase by ten minutes per year in school. (e.g., A third grader would have 30 minutes of homework, while a seventh grader would have 70 minutes).

Studies have found that schools tend to roughly follow these guidelines: The University of Michigan found that students ages six to eight spend 29 minutes doing homework per night while 15- to 17-year-old students spend 50 minutes doing homework. The Metlife study also found that 50 percent of students in grades seven to 12 spent more than an hour a night on homework, while 37 percent of students in grades three to six spent an hour or more on their homework per night. The National Center for Educational Statistics found that high school students who do homework outside of school average 6.8 hours of homework per week.

![how many hours do students spend on homework a day [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_MetlifeGraph.jpg)

Race plays a role in how much homework students do.

Asian students spend 3.5 more hours on average doing homework per week than their white peers. However, only 59 percent of Asian students’ parents check that homework is done, while 75.6 percent of Hispanic students’ parents and 83.1 percent of black students’ parents check.

![how many hours do students spend on homework a day [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_NCESGraph.jpg)

Teachers with less experience assign more homework.

The Metlife study found that 14 percent of teachers with zero to five years of teaching experience assigned more than an hour of homework per night, while only six percent of teachers with 21 or more years of teaching experience assigned over an hour of homework.

![how many hours do students spend on homework a day [IMAGE DESCRIPTION]](https://cdn.theatlantic.com/assets/media/img/posts/Ryan_Homework_GraphTeachers.jpg)

Math classes have homework the most frequently.

The Metlife study found that 70 percent of students in grades three to 12 had at least one homework assignment in math. Sixty-two percent had at least one homework assignment in a language arts class (English, reading, spelling, or creative writing courses) and 42 percent had at least one in a science class.

Regardless of how much homework kids are actually doing every night, most parents and teachers are happy with the way things are: 60 percent of parents think that their children have the “right amount of homework,” and 73 percent of teachers think their school assigns the right amount of homework.

Students, however, are not necessarily on board: 38 percent of students in grades seven through 12 and 28 percent of students in grades three through six report being “very often/often” stressed out by their homework.

About the Author

More Stories

Are 'Tiger Moms' Better Than Cool Moms?

This Is What the New SAT Will Be Like

How Much Homework is Too Much?

When redesigning a course or putting together a new course, faculty often struggle with how much homework and readings to assign. Too little homework and students might not be prepared for the class sessions or be able to adequately practice basic skills or produce sufficient in-depth work to properly master the learning goals of the course. Too much and some students may feel overwhelmed and find it difficult to keep up or have to sacrifice work in other courses.