D.F.W.’s Favorite Grammarian

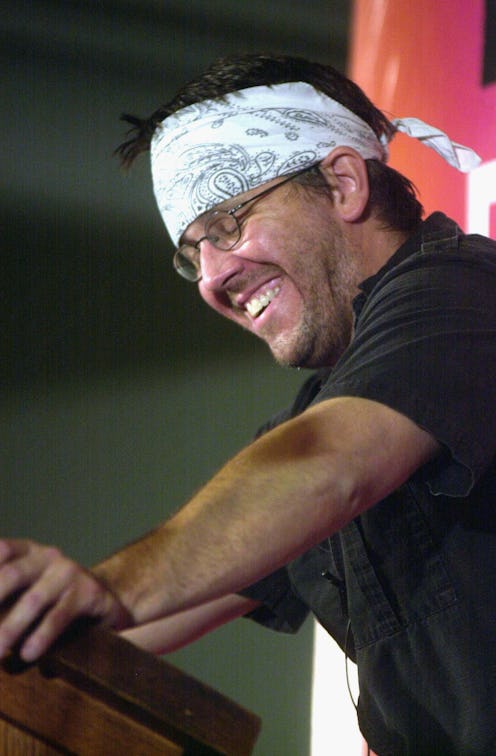

What would David Foster Wallace have made of “Quack This Way,” the recent publication of a 2006 interview he gave on grammar and usage? D.F.W. was first and foremost a writer , and one who mistrusted substituting talk for the more careful arrangements of the page. Interviews with him are full of his misgivings that questions are coming too fast and asking for answers that are too short.

Yet “Quack This Way” is the fourth posthumous publication of the impromptu oral D.F.W. First was David Lipsky’s transcription of his 1996 road trip with the writer ; next was a volume in the “ Conversations With ” series from the University Press of Mississippi, then “ The Last Interview ” (much overlap with the foregoing), and, finally, this discussion with Bryan Garner, a usage expert, conducted in a Los Angeles hotel room in 2006. An additional irony is that what D.F.W. and Garner, a professor of law at Southern Methodist University whose day job is to teach good writing to lawyers, sit down to talk about is the centrality, the permanence, the almost moral imperative to write well. And here D.F.W. is, yammering on.

For readers, I think it’s almost entirely a good thing. Our worries are not D.F.W.’s. He was a brilliant conversationalist, whose best stuff often didn’t make it to the page—our Coleridge, if you like. Ask anyone who knew him, and what they remember is his glorious, discursive, impassioned talk.

And it’s true that even in this new, slender volume, there is always something absorbing, something distinctive, some agitated motion of the inner being that is distinctly Wallace. Here he is on bad professional prose, be it by lawyers or academics:

My guess is that disciplines that are populated by smart, well-educated people who are good readers but are nevertheless characterized by crummy, turgid, verbose, abstruse, abstract, solecism-ridden prose, are usually part of a discipline where the vector of meaning—as a way to get information or opinion from me to you—versus writing, as a form of dress or speech or style … that signals that “I am a member of this group,” gets thrown off.

The interview was a byproduct of an article Wallace started in the late nineties on the grammar wars. Most writers think of grammar as uninteresting, the machine code of literature, but Wallace loved it for many reasons—because his mother did; because it was full of rules, and limits gave him pleasure; and because his mastery of the subject reminded everyone how smart he was. He was, as he would write in the piece, a SNOOT (explained in a footnote as Syntax Nudniks of Our Time). But, to his surprise (and mine, when I began researching “ Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story ”), this was an article that cost him, and into which he sank more deeply than he meant to. “Issues of usage, looked at closely even for a moment,” he wrote to Don DeLillo (whom he was always trying to impress) as he was working on it, “become issues of Everything—from neurology to politics to Aristotelian pisteis to Jaussian Kritik to stuff like etiquette and clothing fashions.” The piece bounced around to several magazines because of its length, and ultimately came out, shortened, in Harper’s in April, 2001, as “Tense Present.” (D.F.W. would reverse the cuts in “Consider the Lobster,” under the title “Authority and American Usage.”)

Wallace’s inquiry centered on Garner’s “A Dictionary of Modern American Usage,” a new entry in the ongoing national battle to communicate without seeming like a fool, a yokel, or a toff. The guide included perennial bugaboos like—or do I mean “such as”?—whether it was O.K. to end a sentence with a preposition (yes, fine) and the admissibility of split infinitives (depends on how many words separate the actual verb and its bereft partner). But for Wallace, the essay also became a way to insert himself into the language wars—and thus into the question of American democracy. Were grammarians supposed to proscribe and prescribe, or just describe? Was usage king or subject? D.F.W. found Garner the ideal mix of instructor and explainer, a teacher with the true credentials of the modest and informed, an authority “not in an autocratic but a technocratic sense.” With a certain self- and subject-mockery, he piled on the encomia. “ADMAU,” he wrote, was “as good as Follett’s…and the handful of other great American usage guides of the century.” Garner he declared “a genius.”

A year later, in 2002, the two met for lunch at Biaggi’s, a Wallace haunt on Veterans Parkway in Bloomington. (Wallace brought his parents.) They exchanged book recommendations; Garner suggested the nineteenth-century critic and grammar authority Richard Grant White, while Wallace proffered his high-lit triad of DeLillo, Gass, and Gaddis. I reached the itinerant professor by phone the other day in a D.C. hotel room—he is on the road two hundred days a year with his Sisyphean mission—and he told me that he and Wallace hadn’t met again until the interview four years afterward, but that they had exchanged letters in the interim. They also each took pleasure in noting the other’s grammatical errors. “That’s the thing about usage,” Garner told me, in his careful way. “When you write copiously, we are all fallible.” He acknowledged that he had started the Gass novel that D.F.W. had recommended—he was not sure of the title—but had not finished it. Nor had he read “Infinite Jest.” “My impression is that it is a book that a lot of people start and don’t finish,” he said levelly. He added that Wallace knew, and didn’t mind. The friendship between the grammar-minded writer and the writing-minded grammarian was the sort that Wallace liked: close, but not too close.

Which may be why, in 2006, Wallace agreed to a videotaped hotel-room interview. Five years had passed since “Tense Present,” during which time D.F.W. had gone from a so-so school, Illinois State University, to a fancy one, Pomona College, and still he spent his days correcting students who mixed up “nauseous” and “nauseated” and struggled to write clearly. He was also on his third president in a row who mangled his grammar, a situation that bothered him acutely. Garner mentioned to me that the Wallace who presented himself at the Hilton Checkers hotel lacked some of the élan of the Wallace of his earlier acquaintance. It’s possible that, in this interim, he began to lose his appetite for a fight that began with his mother’s battles against supermarkets and their “Express Lane Ten Items or Less” signs. Late in the interview, he bursts out to Garner:

And people like you and me, we just don’t have our finger on the pulse anymore. What people are looking for is not the kind of stuff we’re talking about. You’ll want to cut this out [of the interview]. I don’t say that to my students because my line with them is still, “Look, you’re at this elite school, you’re going to end up in the professions…Right? You need to quack this way…. But the truth is that between sophisticated advertising and national-level politics, I am at a loss as to what people’s use of language is now meant to convey and connote to the receiver.”

D.T. Max is the author of “ Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace ,” newly out in paperback.

Illustration by Philip Burke.

8 David Foster Wallace Essays You Can Read Online

If you've talked to me for more than five minutes, you probably know that I'm a huge fan of author and essayist David Foster Wallace . In my opinion, he's one of the most fascinating writers and thinkers that has ever lived, and he possessed an almost supernatural ability to articulate the human experience.

Listen, you don't have to be a pretentious white dude to fall for DFW. I know that stigma is out there, but it's just not true. David Foster Wallace's writing will appeal to anyone who likes to think deeply about the human experience. He really likes to dig into the meat of a moment — from describing state fair roller coaster rides to examining the mind of a detoxing addict. His explorations of the human consciousness are incredibly astute, and I've always felt as thought DFW was actually mapping out my own consciousness.

Contrary to what some may think, the way to become a DFW fan is not to immediately read Infinite Jest . I love Infinite Jest. It's one of my favorite books of all-time. But it is also over 1,000 pages long and extremely difficult to read. It took me seven months to read it for the first time. That's a lot to ask of yourself as a reader.

My recommendation is to start with David Foster Wallace's essays . They are pure gold. I discovered DFW when I was in college, and I would spend hours skiving off my homework to read anything I could get my hands on. Most of what I read I got for free on the Internet.

So, here's your guide to David Foster Wallace on the web. Once you've blown through these, pick up a copy of Consider the Lobster or A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again .

1. "This is Water" Commencement Speech

Technically this is a speech, but it will seriously revolutionize the way you think about the world and how you interact with it. You can listen to Wallace deliver it at Kenyon College , or you can read this transcript . Or, hey, do both.

2. "Consider the Lobster"

This is a classic. When he goes to the Maine Lobster Festival to do a report for Gourmet , DFW ends up taking his readers along for a deep, cerebral ride. Asking questions like "Do lobsters feel pain?" Wallace turns the whole celebration into a profound breakdown on the meaning of consciousness. (Don't forget to read the footnotes!)

2. "Ticket to the Fair"

Another episode of Wallace turning journalism into something more. Harper 's sent DFW to report on the state fair, and he emerged with this masterpiece. The Harper's subtitle says it all: "Wherein our reporter gorges himself on corn dogs, gapes at terrifying rides, savors the odor of pigs, exchanges unpleasantries with tattooed carnies, and admires the loveliness of cows."

3. "Federer as Religious Experience"

DFW was obviously obsessed with tennis, but you don't have to like or know anything about the sport to be drawn in by his writing. In this essay, originally published in the sports section of The New York Times , Wallace delivers a profile on Roger Federer that soon turns into a discussion of beauty with regard to athleticism. It's hypnotizing to read.

4. "Shipping Out: On the (nearly lethal) comforts of a luxury cruise"

Later published as "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again" in the collection of the same name, this essay is the result of Harper's sending Wallace on a luxury cruise. Wallace describes how the cruise sends him into a depressive spiral, detailing the oddities that make up the strange atmosphere of an environment designed for ultimate "fun."

5. "E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction"

This is definitely in the running for my favorite DFW essay. (It's so hard to choose.) Fiction writers! Television! Voyeurism! Loneliness! Basically everything I love comes together in this piece as Wallace dives into a deep exploration of how humans find ways to look at each other. Though it's a little long, it's endlessly fascinating.

6. "String Theory"

"You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it's hard."

Originally published in Esquire , this article takes you deep into the intricate world of professional tennis. Wallace uses tennis (and specifically tennis player Michael Joyce) as a vehicle to explore the ideas of success, identity, and what it means to be a professional athlete.

7. "9/11: The View from the Midwest"

Written in the days following 9/11, this article details DFW and his community's struggle to come to terms with the attack.

8. "Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars Over Usage "

If you're a language nerd like me, you'll really dig this one. A self-proclaimed "snoot" about grammar, Wallace dives into the world of dictionaries, exploring all of the implications of how language is used, how we understand and define grammar, and how the "Democratic Spirit" fits into the tumultuous realms of English.

Images: cocoparisienne /Pixabay; werner22brigette /Pixabay; StartupStockPhotos /Pixabay; PublicDomainPIctures /Pixabay

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Ransom Center Magazine

April 26, 2011 , Filed Under: Exhibitions + Events

In the galleries: David Foster Wallace’s affinity for grammar and usage

David Foster Wallace, who was regarded by many as the best writer of his generation, was a talented essayist who was commissioned by several publications, from Harper’s and The Atlantic Monthly to Rolling Stone and Gourmet , to write on topics as disparate as a luxury cruise, tennis, the Illinois State Fair, and the first presidential campaign of John McCain.

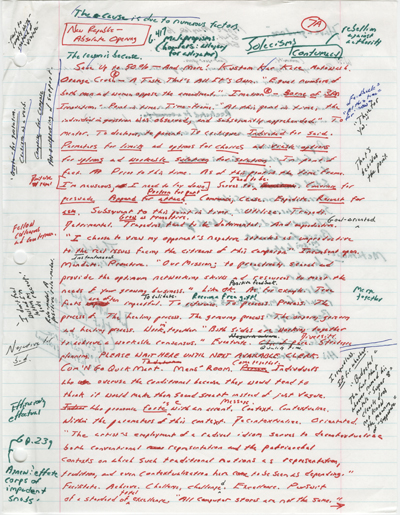

Wallace, whose affinity for and comprehension of the rules of grammar and usage were widely known, published an essay entitled “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars over Usage” in Harper’s in April 2001. An early draft of his essay can be seen in the Ransom Center’s current exhibition, Culture Unbound: Collecting in the Twenty-First Century . The draft is a veritable rainbow, covered in red, black, blue, and green ink. Wallace notes his argument at the bottom of the page: “Language & grammar are the distinctive human attainment. They make possible almost everything we value as human (and beyond: ‘In the beginning was the Word). Facility with language… may be one of our responsibilities (like care of the earth, decency to our fellows).”

David Foster Wallace’s affinity for grammar is also seen in his library, which includes a number of books related to language, usage, and writing. One of his books about the history of the English language is underlined extensively throughout by Wallace. On one page, Wallace highlights with an exclamation point the following text: “[The average person] is likely to forget that writing is only a conventional device for recording sounds and that language is primarily speech.”

It seems that none of Wallace’s books were safe from his inquiring pen. Wallace deeply admired novelist Don DeLillo. His library includes more than a dozen books by DeLillo, whose influence on Wallace can be seen in Wallace’s extensive handwritten notes about the novels and DeLillo’s writing style. On a page of DeLillo’s 1982 novel, The Names , Wallace writes with his red and green pens: “D doesn’t use commas between independent clauses—only uses ‘and.’ See p. 19. Why? It gives narrative a more oral quality—We never hear this comma.”

About Courtney Reed

© Harry Ransom Center 2024

Web Accessibility · Web Privacy

RANSOM CENTER MAGAZINE

- Books + Manuscripts

- Conservation

- Digital Collections

- Exhibitions + Events

- Photography

- Research + Teaching

- Theatre + Performing Arts

- Print Edition

Subscribe to our newsletter

25 great articles and essays by david foster wallace, life and love, this is water, hail the returning dragon, clothed in new fire, words and writing, tense present, deciderization 2007, laughing with kafka, the nature of the fun, fictional futures and the conspicuously young, e unibus pluram: television and u.s. fiction, what words really mean, films, music and the media, david lynch keeps his head, signifying rappers, big red son, see also..., 150 great articles and essays.

Shipping Out

Ticket to the fair, consider the lobster, the string theory, federer as religious experience, tennis, trigonometry, tornadoes, the weasel, twelve monkeys and the shrub, 9/11: the view from the midwest, just asking, a supposedly fun thing i'll never do again, consider the lobster and other essays.

About The Electric Typewriter We search the net to bring you the best nonfiction, articles, essays and journalism

The Definitively Non-Standard English of David Foster Wallace

Article sidebar, main article content.

In his essay “Tense Present,” David Foster Wallace claims that Bryan Garner’s A Dictionary of Modern American Usage is effective because Garner effaces his individuality from the argument: upon finishing ADMAU , the reader has no idea whether Garner is “black or white, gay or straight, Democrat or Dittohead” (57). To Wallace, Garner’s ethical appeal derives from the fact that he does not seem to exist at all, and he doesn’t let his personality get in the way of his argument. But while Wallace claims that Garner is a “genius” (57), he deliberately departs from Garner’s anonymous writing style. In fact, Wallace flaunts his authorial voice, and by the end of the essay the reader is well acquainted with the author. This begs the question: if Wallace so admires Garner’s impersonal approach, why does he appeal to his reader with such different rhetoric?

Indeed, David Foster Wallace shares an awful lot about his past and present life. From the author’s endless digressions, we know that Wallace is a SNOOT, his family’s nickname for a usage fanatic “whose idea of Sunday fun is to look for mistakes in Safire’s column’s prose itself” (41). We know that Wallace, like his mother, is an English teacher. We know that Wallace is the product of a “nuclear family,” his mother being “a SNOOT of the most rabid and intractable sort” and his father being the sort of guy who just “rolled his eyes and drove” while his neurotic family members hollered SNOOT-y songs from the back seat (41). We know that Wallace was the kind of kid who actually wrote these songs, and the kind of kid who actually knew what the word “solecism” means.

In fact, David Foster Wallace seems to go out of his way to share snippets of his Grammar Geek past. This show-and-tell attitude is in complete opposition to Garner’s more anonymous strategy, which can lead the reader to believe that if Garner is a genius, then Wallace must be a nincompoop for projecting himself onto his argument.

But David Foster Wallace does not always write as David Foster Wallace, the Rural Midwestern and SNOOT-y English professor, might be expected to write. He makes liberal use of unconventional words, acronyms, and abbreviations as well as the irregular capitalization of nouns (“SNOOT,” “ ADMAU ,” and “Computer Nerd,” just to name a few) (41). Lexicographic jargon, such as “1-P pronoun,” and extensive footnotes imitate academic prose, and yet within those very same footnotes Wallace has no reservation in bandying about words like “wacko” (51) and “total idiot” (53). Childish speech (such as the “plus” in “ plus also the ‘uncomfortable’ part” and the “sort of” in “it was sort of our family’s version of ‘100 Bottles . . . Wall’”) sits alongside obscure foreign imports such as à clef and Sprachgefühl (41). In fact, David Foster Wallace’s essay uses as many different writing styles as there are dialects of Standard English.

Wallace’s prose has far more character than Garner’s. Indeed, “Tense Present” is appealing precisely because the author’s voice is so pronounced. Thus, what at first appears to be a raving review of Garner’s dictionary becomes an ironic criticism of Garner’s bland but perfect Standard English. Real people don’t speak Garner’s Standard English; real people must be either “black or white, gay or straight, Democrat or Dittohead” (57), and these character traits define how they speak, write, and interact with others. Even though Wallace seems to be defending the existence of Standard English, the vivacity of his prose undercuts his argument. Wallace’s English is not Standard: it is unique among the myriad other dialects spoken around the globe. Thus, he is arguing for diversity in the English language, not against it.

The examples given above prove that Wallace’s writing style is not limited to a single, Standard English voice. The reader hears not only the author’s SNOOT-y English but also Rural Midwestern English, Academic English, Political English, Colloquial English, Simple English, and a never-ending laundry list of variations, permutations, and combinations thereof. Wallace argues that English is a diverse, living language, and its speakers are not limited to educated WASPs, and its written usage is not limited to lexicographic dissertations. English (unlike, for example, Latin, which was deployed as an upper-class trait) is truly democratic because it is used every day in countless contexts by people from all walks of life.

Wallace does not directly broach the issue of the diversity of English in his essay. In this way, Wallace is like Garner in that “his argumentative strategy is totally brilliant and totally sneaky, and part of both qualities is that it usually doesn’t seem like there’s even an argument going on at all” (57). David Foster Wallace lets his words speak for themselves. Even in an essay praising the merits of Standard English, he manages to display the versatility and flexibility of the English language without uttering a word on the subject. His specifically non-Standard choice of words proves that other forms of English can be just as persuasive as Standard English.

Even more brilliant and sneaky is that this undercover rhetoric only reinforces Wallace’s ostensible argument. The fact that individual words define (and support) Wallace’s position vis-à-vis the English language is undeniable proof in favor of Wallace’s fundamental thesis: that words do have power, that language does matter, and that English usage is in fact a political issue. If words have the power to convince, then they also have the power to manipulate, to sway, to incite into action. Anything this powerful is by definition a social concern, and so what does or does not go into the dictionary is an issue of the utmost social, political, and democratic importance.

WORKS CITED

Wallace, David Foster. “Tense Present.” Harper’s Magazine 1 Apr. 2001: 39–58. Print.

Jack Klempay

JACK KLEMPAY 'CC15 is studying Russian Literature and Mathematics. A native of Missoula, Montana, he is an avid reader, writer, and musician. Outside of class, Jack plays cello in Columbia’s chamber, klezmer, and bluegrass ensembles.

Article Details

The Nature of the Fun: David Foster Wallace on Why Writers Write

By maria popova.

After offering an extended and rather gory metaphor for the writer’s creative output and a Zen parable about unpredictability, he gets to the meat of things:

In the beginning, when you first start out trying to write fiction, the whole endeavor’s about fun. You don’t expect anybody else to read it. You’re writing almost wholly to get yourself off. To enable your own fantasies and deviant logics and to escape or transform parts of yourself you don’t like. And it works – and it’s terrific fun. Then, if you have good luck and people seem to like what you do, and you actually start to get paid for it, and get to see your stuff professionally typeset and bound and blurbed and reviewed and even (once) being read on the a.m. subway by a pretty girl you don’t even know it seems to make it even more fun. For a while. Then things start to get complicated and confusing, not to mention scary. Now you feel like you’re writing for other people, or at least you hope so. You’re no longer writing just to get yourself off, which — since any kind of masturbation is lonely and hollow — is probably good. But what replaces the onanistic motive? You’ve found you very much enjoy having your writing liked by people, and you find you’re extremely keen to have people like the new stuff you’re doing. The motive of pure personal starts to get supplanted by the motive of being liked, of having pretty people you don’t know like you and admire you and think you’re a good writer. Onanism gives way to attempted seduction, as a motive. Now, attempted seduction is hard work, and its fun is offset by a terrible fear of rejection. Whatever “ego” means, your ego has now gotten into the game. Or maybe “vanity” is a better word. Because you notice that a good deal of your writing has now become basically showing off, trying to get people to think you’re good. This is understandable. You have a great deal of yourself on the line, writing — your vanity is at stake. You discover a tricky thing about fiction writing; a certain amount of vanity is necessary to be able to do it all, but any vanity above that certain amount is lethal.

Here, Wallace echoes Vonnegut, who famously advised , “Write to please just one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.” Indeed, this lusting after prestige and approval is a familiar detractor of creative purpose in any endeavor. Wallace goes on:

At some point you find that 90% of the stuff you’re writing is motivated and informed by an overwhelming need to be liked. This results in shitty fiction. And the shitty work must get fed to the wastebasket, less because of any sort of artistic integrity than simply because shitty work will cause you to be disliked. At this point in the evolution of writerly fun, the very thing that’s always motivated you to write is now also what’s motivating you to feed your writing to the wastebasket. This is a paradox and a kind of double-bind, and it can keep you stuck inside yourself for months or even years, during which period you wail and gnash and rue your bad luck and wonder bitterly where all the fun of the thing could have gone.

He adds to literary history’s most famous insights on the relationship between truth and fiction :

The smart thing to say, I think, is that the way out of this bind is to work your way somehow back to your original motivation — fun. And, if you can find your way back to fun, you will find that the hideously unfortunate double-bind of the late vain period turns out really to have been good luck for you. Because the fun you work back to has been transfigured by the extreme unpleasantness of vanity and fear, an unpleasantness you’re now so anxious to avoid that the fun you rediscover is a way fuller and more large-hearted kind of fun. It has something to do with Work as Play. Or with the discovery that disciplined fun is more than impulsive or hedonistic fun. Or with figuring out that not all paradoxes have to be paralyzing. Under fun’s new administration, writing fiction becomes a way to go deep inside yourself and illuminate precisely the stuff you don’t want to see or let anyone else see, and this stuff usually turns out (paradoxically) to be precisely the stuff all writers and readers everywhere share and respond to, feel. Fiction becomes a weird way to countenance yourself and to tell the truth instead of being a way to escape yourself or present yourself in a way you figure you will be maximally likable. This process is complicated and confusing and scary, and also hard work, but it turns out to be the best fun there is.

He concludes on a Bradbury-like note:

The fact that you can now sustain the fun of writing only by confronting the very same unfun parts of yourself you’d first used writing to avoid or disguise is another paradox, but this one isn’t any kind of bind at all. What it is is a gift, a kind of miracle, and compared to it the rewards of strangers’ affection is as dust, lint.

Both Flesh and Not is excellent in its entirety and just as quietly, unflinchingly soul-stirring as “The Nature of the Fun.”

— Published November 6, 2012 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/11/06/the-nature-of-fun-david-foster-wallace/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books creativity david foster wallace psychology writing, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

For David Foster Wallace, grammar was a way to insert himself into the language wars, and into the question of democracy.

BY DAVID FOSTER WALLACE Davw. ... DiscUssed in this essay: A Dictiorlary of Modem American Usage, by Bryan A, Garner, Oxford University Press, 1998. 723 pages. $35. .

A self-proclaimed "snoot" about grammar, Wallace dives into the world of dictionaries, exploring all of the implications of how language is used, how we understand and define grammar, and how...

Wallace argues that one of the most important points of awareness, and one of the most shocking to aspiring writers, can be summed up thusly: “I am not, in and of myself, interesting to a reader. If I want to seem interesting, work has to be done in order to make myself interesting.”.

David Foster Wallace, whose affinity for and comprehension of the rules of grammar and usage were widely known, published an essay entitled “Tense Present: Democracy, English, and the Wars over Usage” in Harper’s in April 2001.

Descriptivists and English-Ed specialists counter that grammar and usage have been abandoned because scientific research proved that studying SWE grammar and usage simply doesn't help make kids...

Perhaps the finest review of an English usage dictionary - this classic essay touches on everything from race bias in academia and the evolution of language to the pros and cons on non-standard English.

In fact, David Foster Wallace’s essay uses as many different writing styles as there are dialects of Standard English. Wallace’s prose has far more character than Garner’s. Indeed, “Tense Present” is appealing precisely because the author’s voice is so pronounced.

Conversations with David Foster Wallace is revelational in its entirety. Complement it with his timeless wisdom on why writers write, the original audio of that mythic Kenyon commencement speech, and Wallace’s animated advice on ambition.

Among the anthology’s finest is an essay titled “The Nature of the Fun” — a meditation on why writers write, encrusted in Wallace’s signature blend of self-conscious despondency, even more self-conscious optimism, and overwhelming self-awareness.