Brainstorming

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses techniques that will help you start writing a paper and continue writing through the challenges of the revising process. Brainstorming can help you choose a topic, develop an approach to a topic, or deepen your understanding of the topic’s potential.

Introduction

If you consciously take advantage of your natural thinking processes by gathering your brain’s energies into a “storm,” you can transform these energies into written words or diagrams that will lead to lively, vibrant writing. Below you will find a brief discussion of what brainstorming is, why you might brainstorm, and suggestions for how you might brainstorm.

Whether you are starting with too much information or not enough, brainstorming can help you to put a new writing task in motion or revive a project that hasn’t reached completion. Let’s take a look at each case:

When you’ve got nothing: You might need a storm to approach when you feel “blank” about the topic, devoid of inspiration, full of anxiety about the topic, or just too tired to craft an orderly outline. In this case, brainstorming stirs up the dust, whips some air into our stilled pools of thought, and gets the breeze of inspiration moving again.

When you’ve got too much: There are times when you have too much chaos in your brain and need to bring in some conscious order. In this case, brainstorming forces the mental chaos and random thoughts to rain out onto the page, giving you some concrete words or schemas that you can then arrange according to their logical relations.

Brainstorming techniques

What follows are great ideas on how to brainstorm—ideas from professional writers, novice writers, people who would rather avoid writing, and people who spend a lot of time brainstorming about…well, how to brainstorm.

Try out several of these options and challenge yourself to vary the techniques you rely on; some techniques might suit a particular writer, academic discipline, or assignment better than others. If the technique you try first doesn’t seem to help you, move right along and try some others.

Freewriting

When you freewrite, you let your thoughts flow as they will, putting pen to paper and writing down whatever comes into your mind. You don’t judge the quality of what you write and you don’t worry about style or any surface-level issues, like spelling, grammar, or punctuation. If you can’t think of what to say, you write that down—really. The advantage of this technique is that you free up your internal critic and allow yourself to write things you might not write if you were being too self-conscious.

When you freewrite you can set a time limit (“I’ll write for 15 minutes!”) and even use a kitchen timer or alarm clock or you can set a space limit (“I’ll write until I fill four full notebook pages, no matter what tries to interrupt me!”) and just write until you reach that goal. You might do this on the computer or on paper, and you can even try it with your eyes shut or the monitor off, which encourages speed and freedom of thought.

The crucial point is that you keep on writing even if you believe you are saying nothing. Word must follow word, no matter the relevance. Your freewriting might even look like this:

“This paper is supposed to be on the politics of tobacco production but even though I went to all the lectures and read the book I can’t think of what to say and I’ve felt this way for four minutes now and I have 11 minutes left and I wonder if I’ll keep thinking nothing during every minute but I’m not sure if it matters that I am babbling and I don’t know what else to say about this topic and it is rainy today and I never noticed the number of cracks in that wall before and those cracks remind me of the walls in my grandfather’s study and he smoked and he farmed and I wonder why he didn’t farm tobacco…”

When you’re done with your set number of minutes or have reached your page goal, read back over the text. Yes, there will be a lot of filler and unusable thoughts but there also will be little gems, discoveries, and insights. When you find these gems, highlight them or cut and paste them into your draft or onto an “ideas” sheet so you can use them in your paper. Even if you don’t find any diamonds in there, you will have either quieted some of the noisy chaos or greased the writing gears so that you can now face the assigned paper topic.

Break down the topic into levels

Once you have a course assignment in front of you, you might brainstorm:

- the general topic, like “The relationship between tropical fruits and colonial powers”

- a specific subtopic or required question, like “How did the availability of multiple tropical fruits influence competition amongst colonial powers trading from the larger Caribbean islands during the 19th century?”

- a single term or phrase that you sense you’re overusing in the paper. For example: If you see that you’ve written “increased the competition” about a dozen times in your “tropical fruits” paper, you could brainstorm variations on the phrase itself or on each of the main terms: “increased” and “competition.”

Listing/bulleting

In this technique you jot down lists of words or phrases under a particular topic. You can base your list on:

- the general topic

- one or more words from your particular thesis claim

- a word or idea that is the complete opposite of your original word or idea.

For example, if your general assignment is to write about the changes in inventions over time, and your specific thesis claims that “the 20th century presented a large number of inventions to advance US society by improving upon the status of 19th-century society,” you could brainstorm two different lists to ensure you are covering the topic thoroughly and that your thesis will be easy to prove.

The first list might be based on your thesis; you would jot down as many 20th-century inventions as you could, as long as you know of their positive effects on society. The second list might be based on the opposite claim, and you would instead jot down inventions that you associate with a decline in that society’s quality. You could do the same two lists for 19th-century inventions and then compare the evidence from all four lists.

Using multiple lists will help you to gather more perspective on the topic and ensure that, sure enough, your thesis is solid as a rock, or, …uh oh, your thesis is full of holes and you’d better alter your claim to one you can prove.

3 perspectives

Looking at something from different perspectives helps you see it more completely—or at least in a completely different way, sort of like laying on the floor makes your desk look very different to you. To use this strategy, answer the questions for each of the three perspectives, then look for interesting relationships or mismatches you can explore:

- Describe it: Describe your subject in detail. What is your topic? What are its components? What are its interesting and distinguishing features? What are its puzzles? Distinguish your subject from those that are similar to it. How is your subject unlike others?

- Trace it: What is the history of your subject? How has it changed over time? Why? What are the significant events that have influenced your subject?

- Map it: What is your subject related to? What is it influenced by? How? What does it influence? How? Who has a stake in your topic? Why? What fields do you draw on for the study of your subject? Why? How has your subject been approached by others? How is their work related to yours?

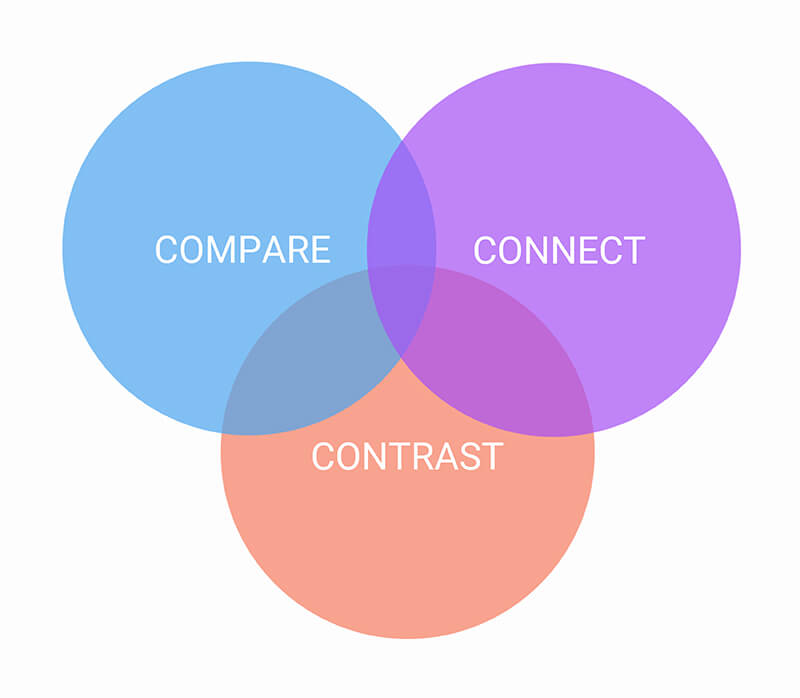

Cubing enables you to consider your topic from six different directions; just as a cube is six-sided, your cubing brainstorming will result in six “sides” or approaches to the topic. Take a sheet of paper, consider your topic, and respond to these six commands:

- Describe it.

- Compare it.

- Associate it.

- Analyze it.

- Argue for and against it.

Look over what you’ve written. Do any of the responses suggest anything new about your topic? What interactions do you notice among the “sides”? That is, do you see patterns repeating, or a theme emerging that you could use to approach the topic or draft a thesis? Does one side seem particularly fruitful in getting your brain moving? Could that one side help you draft your thesis statement? Use this technique in a way that serves your topic. It should, at least, give you a broader awareness of the topic’s complexities, if not a sharper focus on what you will do with it.

In this technique, complete the following sentence:

____________________ is/was/are/were like _____________________.

In the first blank put one of the terms or concepts your paper centers on. Then try to brainstorm as many answers as possible for the second blank, writing them down as you come up with them.

After you have produced a list of options, look over your ideas. What kinds of ideas come forward? What patterns or associations do you find?

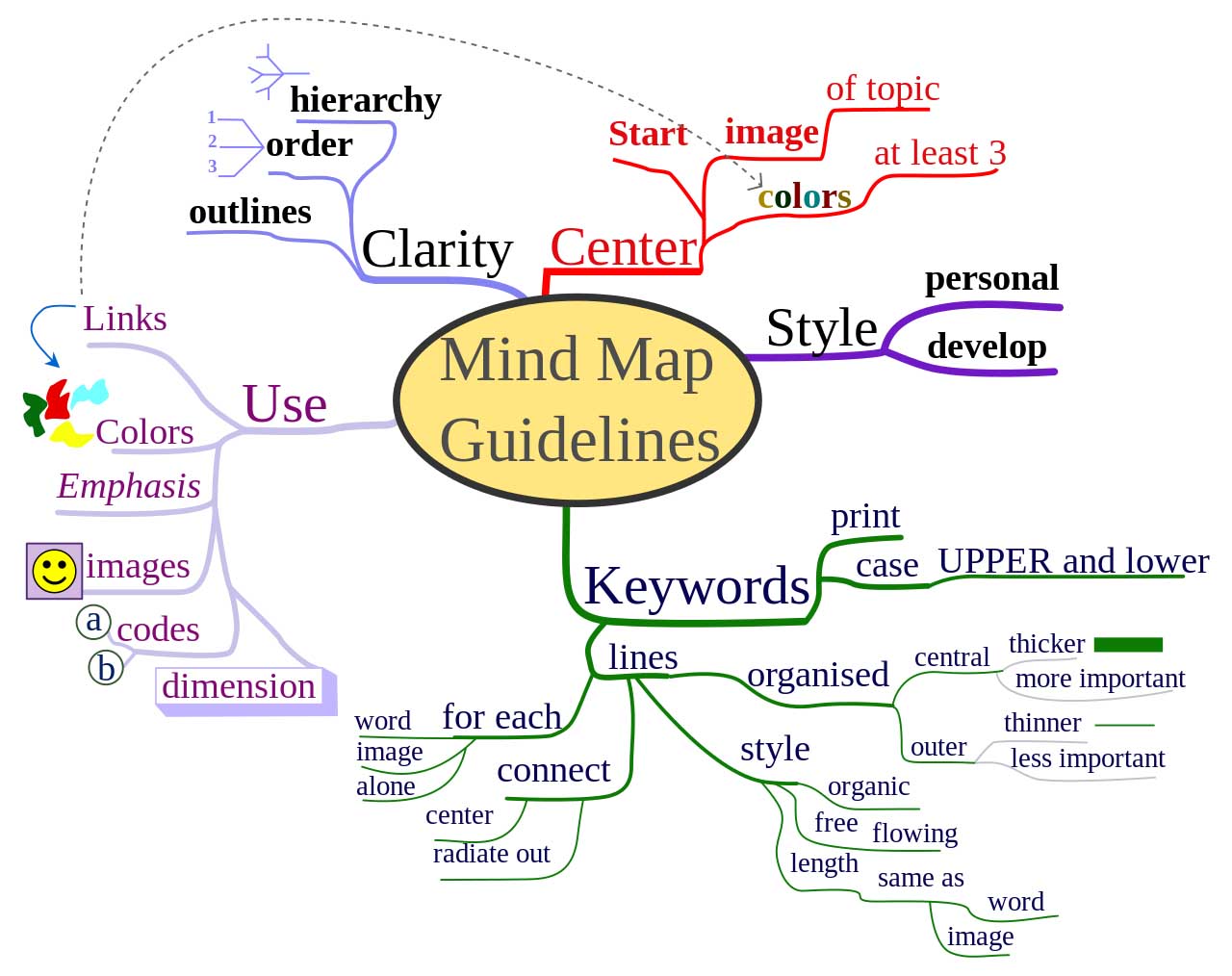

Clustering/mapping/webbing:

The general idea:

This technique has three (or more) different names, according to how you describe the activity itself or what the end product looks like. In short, you will write a lot of different terms and phrases onto a sheet of paper in a random fashion and later go back to link the words together into a sort of “map” or “web” that forms groups from the separate parts. Allow yourself to start with chaos. After the chaos subsides, you will be able to create some order out of it.

To really let yourself go in this brainstorming technique, use a large piece of paper or tape two pieces together. You could also use a blackboard if you are working with a group of people. This big vertical space allows all members room to “storm” at the same time, but you might have to copy down the results onto paper later. If you don’t have big paper at the moment, don’t worry. You can do this on an 8 ½ by 11 as well. Watch our short videos on webbing , drawing relationships , and color coding for demonstrations.

How to do it:

- Take your sheet(s) of paper and write your main topic in the center, using a word or two or three.

- Moving out from the center and filling in the open space any way you are driven to fill it, start to write down, fast, as many related concepts or terms as you can associate with the central topic. Jot them quickly, move into another space, jot some more down, move to another blank, and just keep moving around and jotting. If you run out of similar concepts, jot down opposites, jot down things that are only slightly related, or jot down your grandpa’s name, but try to keep moving and associating. Don’t worry about the (lack of) sense of what you write, for you can chose to keep or toss out these ideas when the activity is over.

- Once the storm has subsided and you are faced with a hail of terms and phrases, you can start to cluster. Circle terms that seem related and then draw a line connecting the circles. Find some more and circle them and draw more lines to connect them with what you think is closely related. When you run out of terms that associate, start with another term. Look for concepts and terms that might relate to that term. Circle them and then link them with a connecting line. Continue this process until you have found all the associated terms. Some of the terms might end up uncircled, but these “loners” can also be useful to you. (Note: You can use different colored pens/pencils/chalk for this part, if you like. If that’s not possible, try to vary the kind of line you use to encircle the topics; use a wavy line, a straight line, a dashed line, a dotted line, a zigzaggy line, etc. in order to see what goes with what.)

- There! When you stand back and survey your work, you should see a set of clusters, or a big web, or a sort of map: hence the names for this activity. At this point you can start to form conclusions about how to approach your topic. There are about as many possible results to this activity as there are stars in the night sky, so what you do from here will depend on your particular results. Let’s take an example or two in order to illustrate how you might form some logical relationships between the clusters and loners you’ve decided to keep. At the end of the day, what you do with the particular “map” or “cluster set” or “web” that you produce depends on what you need. What does this map or web tell you to do? Explore an option or two and get your draft going!

Relationship between the parts

In this technique, begin by writing the following pairs of terms on opposite margins of one sheet of paper:

Looking over these four groups of pairs, start to fill in your ideas below each heading. Keep going down through as many levels as you can. Now, look at the various parts that comprise the parts of your whole concept. What sorts of conclusions can you draw according to the patterns, or lack of patterns, that you see? For a related strategy, watch our short video on drawing relationships .

Journalistic questions

In this technique you would use the “big six” questions that journalists rely on to thoroughly research a story. The six are: Who?, What?, When?, Where?, Why?, and How?. Write each question word on a sheet of paper, leaving space between them. Then, write out some sentences or phrases in answer, as they fit your particular topic. You might also record yourself or use speech-to-text if you’d rather talk out your ideas.

Now look over your batch of responses. Do you see that you have more to say about one or two of the questions? Or, are your answers for each question pretty well balanced in depth and content? Was there one question that you had absolutely no answer for? How might this awareness help you to decide how to frame your thesis claim or to organize your paper? Or, how might it reveal what you must work on further, doing library research or interviews or further note-taking?

For example, if your answers reveal that you know a lot more about “where” and “why” something happened than you know about “what” and “when,” how could you use this lack of balance to direct your research or to shape your paper? How might you organize your paper so that it emphasizes the known versus the unknown aspects of evidence in the field of study? What else might you do with your results?

Thinking outside the box

Even when you are writing within a particular academic discipline, you can take advantage of your semesters of experience in other courses from other departments. Let’s say you are writing a paper for an English course. You could ask yourself, “Hmmm, if I were writing about this very same topic in a biology course or using this term in a history course, how might I see or understand it differently? Are there varying definitions for this concept within, say, philosophy or physics, that might encourage me to think about this term from a new, richer point of view?”

For example, when discussing “culture” in your English, communications, or cultural studies course, you could incorporate the definition of “culture” that is frequently used in the biological sciences. Remember those little Petri dishes from your lab experiments in high school? Those dishes are used to “culture” substances for bacterial growth and analysis, right? How might it help you write your paper if you thought of “culture” as a medium upon which certain things will grow, will develop in new ways or will even flourish beyond expectations, but upon which the growth of other things might be retarded, significantly altered, or stopped altogether?

Using charts or shapes

If you are more visually inclined, you might create charts, graphs, or tables in lieu of word lists or phrases as you try to shape or explore an idea. You could use the same phrases or words that are central to your topic and try different ways to arrange them spatially, say in a graph, on a grid, or in a table or chart. You might even try the trusty old flow chart. The important thing here is to get out of the realm of words alone and see how different spatial representations might help you see the relationships among your ideas. If you can’t imagine the shape of a chart at first, just put down the words on the page and then draw lines between or around them. Or think of a shape. Do your ideas most easily form a triangle? square? umbrella? Can you put some ideas in parallel formation? In a line?

Consider purpose and audience

Think about the parts of communication involved in any writing or speaking act: purpose and audience.

What is your purpose?

What are you trying to do? What verb captures your intent? Are you trying to inform? Convince? Describe? Each purpose will lead you to a different set of information and help you shape material to include and exclude in a draft. Write about why you are writing this draft in this form. For more tips on figuring out the purpose of your assignment, see our handout on understanding assignments .

Who is your audience?

Who are you communicating with beyond the grader? What does that audience need to know? What do they already know? What information does that audience need first, second, third? Write about who you are writing to and what they need. For more on audience, see our handout on audience .

Dictionaries, thesauruses, encyclopedias

When all else fails…this is a tried and true method, loved for centuries by writers of all stripe. Visit the library reference areas or stop by the Writing Center to browse various dictionaries, thesauruses (or other guide books and reference texts), encyclopedias or surf their online counterparts. Sometimes these basic steps are the best ones. It is almost guaranteed that you’ll learn several things you did not know.

If you’re looking at a hard copy reference, turn to your most important terms and see what sort of variety you find in the definitions. The obscure or archaic definition might help you to appreciate the term’s breadth or realize how much its meaning has changed as the language changed. Could that realization be built into your paper somehow?

If you go to online sources, use their own search functions to find your key terms and see what suggestions they offer. For example, if you plug “good” into a thesaurus search, you will be given 14 different entries. Whew! If you were analyzing the film Good Will Hunting, imagine how you could enrich your paper by addressed the six or seven ways that “good” could be interpreted according to how the scenes, lighting, editing, music, etc., emphasized various aspects of “good.”

An encyclopedia is sometimes a valuable resource if you need to clarify facts, get quick background, or get a broader context for an event or item. If you are stuck because you have a vague sense of a seemingly important issue, do a quick check with this reference and you may be able to move forward with your ideas.

Armed with a full quiver of brainstorming techniques and facing sheets of jotted ideas, bulleted subtopics, or spidery webs relating to your paper, what do you do now?

Take the next step and start to write your first draft, or fill in those gaps you’ve been brainstorming about to complete your “almost ready” paper. If you’re a fan of outlining, prepare one that incorporates as much of your brainstorming data as seems logical to you. If you’re not a fan, don’t make one. Instead, start to write out some larger chunks (large groups of sentences or full paragraphs) to expand upon your smaller clusters and phrases. Keep building from there into larger sections of your paper. You don’t have to start at the beginning of the draft. Start writing the section that comes together most easily. You can always go back to write the introduction later.

We also have helpful handouts on some of the next steps in your writing process, such as reorganizing drafts and argument .

Remember, once you’ve begun the paper, you can stop and try another brainstorming technique whenever you feel stuck. Keep the energy moving and try several techniques to find what suits you or the particular project you are working on.

How can technology help?

Need some help brainstorming? Different digital tools can help with a variety of brainstorming strategies:

Look for a text editor that has a focus mode or that is designed to promote free writing (for examples, check out FocusWriter, OmmWriter, WriteRoom, Writer the Internet Typewriter, or Cold Turkey). Eliminating visual distractions on your screen can help you free write for designated periods of time. By eliminating visual distractions on your screen, these tools help you focus on free writing for designated periods of time. If you use Microsoft Word, you might even try “Focus Mode” under the “View” tab.

Clustering/mapping. Websites and applications like Mindomo , TheBrain , and Miro allow you to create concept maps and graphic organizers. These applications often include the following features:

- Connect links, embed documents and media, and integrate notes in your concept maps

- Access your maps across devices

- Search across maps for keywords

- Convert maps into checklists and outlines

- Export maps to other file formats

Testimonials

Check out what other students and writers have tried!

Papers as Puzzles : A UNC student demonstrates a brainstorming strategy for getting started on a paper.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Allen, Roberta, and Marcia Mascolini. 1997. The Process of Writing: Composing Through Critical Thinking . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Cameron, Julia. 2002. The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity . New York: Putnam.

Goldberg, Natalie. 2005. Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within , rev. ed. Boston: Shambhala.

Rosen, Leonard J. and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

University of Richmond. n.d. “Main Page.” Writer’s Web. Accessed June 14, 2019. http://writing2.richmond.edu/writing/wweb.html .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Module 6: The Writing Process

Brainstorming and freewriting, learning objectives.

- Explain how brainstorming and freewriting can help you start writing

Chances are you have learned about brainstorming in your other English courses. If not, then maybe you make lists or charts to help you make a decision in your life. Perhaps you have worked a job where you had to solve a problem with your coworkers so you listed ideas that helped you get started. When you writing in college, it’s helpful to get some ideas down before you write. As you begin thinking about a topic, before you begin your official draft, you write down ideas and concepts associated with your assignment to develop your ideas. This is a critical step in helping to shape and organize your paper. Brainstorming and freewriting are two great ways to get started.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming allows you to quickly generate a large number of ideas. You can brainstorm with others or you can brainstorm by yourself, which sometimes turns into freewriting. To effectively brainstorm, write down whatever ideas come to mind. The key is to not place judgment on what you wrote. Don’t worry about whether it sounds smart or if it directly connects to your topic. To brainstorm, let your thoughts about a specific topic flow, and list those thoughts without stopping or judging if what you are writing about is any good.

Let’s take a look at an easy example. Say you are being asked to write an essay about squirrels, and you’re not particularly sure what you would like to write about since you’ve never thought too much about the squirrels in your yard. The goal is to get down as many thoughts as possible in order to answer a question.

Example: What do I know about squirrels?

- How to get them out of the garden

- Squirrel traps

- Repellents for squirrels

- Types of squirrels

- How to get rid of them humanely (without killing)

- Brown vs. black vs. red squirrels

- Flying squirrels

- What they eat

- Different types of play

- Training squirrels

- Hunting squirrels

- Squirrels and cats

- Squirrels and dogs

- How they nest

- Build nests in the same place each year

So, what happens once you’ve brainstormed a topic? Look over the list. Are there items that group together? Are there items that catch your interest as a thinker, researcher, and writer—items you want to know more about? Are there items that seem unrelated or not useful? Use your list as a starting place; it creates ideas for you, as a writer, to work with in your paper. If you look closely at this list, do you see topics that could be grouped together?

Sometimes it works better to write down each idea on a separate piece of paper. Some people like to type their ideas. The most important part of this process is to be curious about your topic.

It also helps to ask yourself some brainstorming questions:

- What am I interested in? What do I care about?

- What do I know that I could teach others?

- What would I like to change about this issue?

In order to capture more of your thoughts, you may want to brainstorm a few times until you have enough ideas to start writing.

Brainstorming Assignment Example

Imagine you are in a class. Your instructor says you will have to write a paper on your favorite freetime activity , and that you must also persuade your reader to try it.

- ice skating

- writing poetry

- playing the piano

- swimming lessons

Let’s think of another example. How about the common situation in which the instructor wants you to write about “something you care about” or an “issue you have” ?

- An example of something small that’s irritating could be people you live with who leave trails of toothpaste by the sink and never clean up after themselves. A personal example can be useful as a bridge to a larger issue that will be your topic—in this case it could be community living and personal responsibility.

- In academic writing with a less personal slant, the source of irritation is often another writer/theorist with whom you disagree. Your “irritation” then would lead to an effective piece about why you have a better conception of what’s really going on.

- A less direct version of this would be a writer/theorist who makes some good points but lacks something in his/her argument that you can add to the “conversation.”

Maybe you already have a method that works for you and it looks nothing like this process. Do you answer the brainstorming questions with your process?

Freewriting

Freewriting is just what it says—writing freely, whatever comes into your mind, without caring about spelling, punctuation, etc. It’s a way to free up your thoughts, help you know where your interests lie, and get your fingers moving on the keyboard (and this physical act can be a way to get your thoughts flowing).

Try a series of timed freewritings. Set a timer for five minutes. The object is to keep your fingers moving constantly and write down whatever thoughts come into your head during that time. If you can’t think of anything to say on your topic, keep writing what comes to mind. Thinking about what you need at the grocery store? Write that down. Thinking about what you need to do for your math class? Write that down too. Stop when the timer rings. Shake out your hands, wait awhile, and then do more timed freewriting. After you have a set of five or so freewritings, review them to see if you’ve come back to certain topics, or whether you recorded some ideas that might be the basis for a piece of writing.

Freewriting Example

Here’s a sample freewrite that could yield a number of topics for writing:

I don’t think this is useful or helpful in any way. This is stupid, stupid, stupid. I’m looking out of my window and it’s the end of may and I can see that white cotton stuff flying around in the air, from the trees. One of my aunts was always allergic to that stuff when it started flying around in the spring. Don’t know offhand what type of tree that comes from. That aunt is now 94 years old and is in a nursing home for a while after she had a bad episode. She seems to have one now every spring. It’s like that old tree cotton triggers something in her body. Allergies. Spring. Trying to get the flowers to grow but one of the neighbors who is also in his 90s keeps feeding the squirrels and they come and dig up everyone’s flowerbed to store their peanuts. Plant the flowers and within thirty minutes there’s a peanut there. Wonder if anyone has grown peanut bushes yet?

Don’t know . . . know . . .I really need to buy pesto for tonight’s dinner.

Possible topics from this freewrite:

- Allergy causes

- Allergies on the rise in the U.S.

- Consequences of humanizing wild animals

- Squirrel behavior patterns and feeding habits

- Growing your own food

- Brainstorming. Authored by : Marianne Botos, Lynn McClelland, Stephanie Polliard, Pamela Osback . Located at : https://pvccenglish.files.wordpress.com/2010/09/eng-101-inside-pages-proof2-no-pro.pdf . Project : Horse of a Different Color: English Composition and Rhetoric . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Brainstorming. Provided by : Excelsior College OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/prewriting-strategies/prewriting-strategies-brainstorming/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Freewriting. Provided by : Excelsior OWL. Located at : https://owl.excelsior.edu/writing-process/prewriting-strategies/prewriting-strategies-freewriting/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Enroll & Pay

- Jayhawk GPS

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Prewriting Strategies

Five useful strategies.

Pre-writing strategies use writing to generate and clarify ideas. While many writers have traditionally created outlines before beginning writing, there are several other effective prewriting activities. We often call these prewriting strategies “brainstorming techniques.” Five useful strategies are listing, clustering, freewriting, looping, and asking the six journalists' questions. These strategies help you with both your invention and organization of ideas, and they can aid you in developing topics for your writing.

Listing is a process of producing a lot of information within a short time by generating some broad ideas and then building on those associations for more detail with a bullet point list. Listing is particularly useful if your starting topic is very broad, and you need to narrow it down.

- Jot down all the possible terms that emerge from the general topic you are working on. This procedure works especially well if you work in a team. All team members can generate ideas, with one member acting as scribe. Do not worry about editing or throwing out what might not be a good idea. Simply write down as many possibilities as you can.

- Group the items that you have listed according to arrangements that make sense to you. Are things thematically related?

- Give each group a label. Now you have a narrower topic with possible points of development.

- Write a sentence about the label you have given the group of ideas. Now you have a topic sentence or possibly a thesis statement .

Clustering, also called mind mapping or idea mapping, is a strategy that allows you to explore the relationships between ideas.

- Put the subject in the center of a page. Circle or underline it.

- As you think of other ideas, write them on the page surrounding the central idea. Link the new ideas to the central circle with lines.

- As you think of ideas that relate to the new ideas, add to those in the same way.

The result will look like a web on your page. Locate clusters of interest to you, and use the terms you attached to the key ideas as departure points for your paper.

Clustering is especially useful in determining the relationship between ideas. You will be able to distinguish how the ideas fit together, especially where there is an abundance of ideas. Clustering your ideas lets you see them visually in a different way, so that you can more readily understand possible directions your paper may take.

Freewriting

Freewriting is a process of generating a lot of information by writing non-stop in full sentences for a predetermined amount of time. It allows you to focus on a specific topic but forces you to write so quickly that you are unable to edit any of your ideas.

- Freewrite on the assignment or general topic for five to ten minutes non-stop. Force yourself to continue writing even if nothing specific comes to mind (so you could end up writing “I don’t know what to write about” over and over until an idea pops into your head. This is okay; the important thing is that you do not stop writing). This freewriting will include many ideas; at this point, generating ideas is what is important, not the grammar or the spelling.

- After you have finished freewriting, look back over what you have written and highlight the most prominent and interesting ideas; then you can begin all over again, with a tighter focus (see looping). You will narrow your topic and, in the process, you will generate several relevant points about the topic.

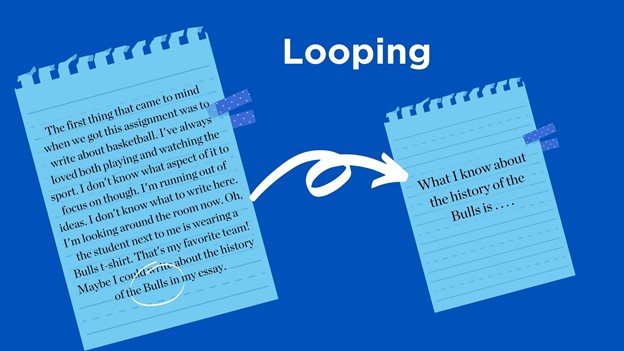

Looping is a freewriting technique that allows you to focus your ideas continually while trying to discover a writing topic. After you freewrite for the first time, identify a key thought or idea in your writing, and begin to freewrite again, with that idea as your starting point. You will loop one 5-10 minute freewriting after another, so you have a sequence of freewritings, each more specific than the last. The same rules that apply to freewriting apply to looping: write quickly, do not edit, and do not stop.

Loop your freewriting as many times as necessary, circling another interesting topic, idea, phrase, or sentence each time. When you have finished four or five rounds of looping, you will begin to have specific information that indicates what you are thinking about a particular topic. You may even have the basis for a tentative thesis or an improved idea for an approach to your assignment when you have finished.

The Journalists' Questions

Journalists traditionally ask six questions when they are writing assignments that are broken down into five W's and one H: Who? , What? , Where? , When? , Why? , and How? You can use these questions to explore the topic you are writing about for an assignment. A key to using the journalists' questions is to make them flexible enough to account for the specific details of your topic. For instance, if your topic is the rise and fall of the Puget Sound tides and its effect on salmon spawning, you may have very little to say about Who if your focus does not account for human involvement. On the other hand, some topics may be heavy on the Who , especially if human involvement is a crucial part of the topic.

The journalists' questions are a powerful way to develop a great deal of information about a topic very quickly. Learning to ask the appropriate questions about a topic takes practice, however. At times during writing an assignment, you may wish to go back and ask the journalists' questions again to clarify important points that may be getting lost in your planning and drafting.

Possible generic questions you can ask using the six journalists' questions follow:

- Who? Who are the participants? Who is affected? Who are the primary actors? Who are the secondary actors?

- What? What is the topic? What is the significance of the topic? What is the basic problem? What are the issues related to that problem?

- Where? Where does the activity take place? Where does the problem or issue have its source? At what place is the cause or effect of the problem most visible?

- When? When is the issue most apparent? (in the past? present? future?) When did the issue or problem develop? What historical forces helped shape the problem or issue and at what point in time will the problem or issue culminate in a crisis? When is action needed to address the issue or problem?

- Why? Why did the issue or problem arise? Why is it (your topic) an issue or problem at all? Why did the issue or problem develop in the way that it did?

- How? How is the issue or problem significant? How can it be addressed? How does it affect the participants? How can the issue or problem be resolved?

Take 10% OFF— Expires in h m s Use code save10u during checkout.

Chat with us

- Live Chat Talk to a specialist

- Self-service options

- Search FAQs Fast answers, no waiting

- Ultius 101 New client? Click here

- Messenger

International support numbers

For reference only, subject to Terms and Fair Use policies.

- How it Works

Learn more about us

- Future writers

- Explore further

Ultius Blog

What is the purpose of freewriting during the research process.

Select network

Knowing how and where to begin writing a research paper can often be quite intimidating. For many students and professionals, freewriting is practice that helps writers overcome that pesky obstacle called writer’s block .

In this blog, we’ll talk about what exactly freewriting is, its purpose during the research process, why it’s important, how to “freewrite”, as well as some final tips for getting the most out of freewriting.

When it’s all said and done, you will be equipped with the know-how of doing your own freewriting. If you don’t have the time to learn about (or do) freewriting, we strongly recommend you read our how-to guide to learn what is speedwriting (it’s just as useful).

The purpose and importance of freewriting

What is freewriting.

Have you ever prepared for a workout by stretching, or gotten ready for a dinner party by browsing your favorite cookbook? Freewriting is a similar process. It’s essentially a way of preparing to write a research paper. During freewriting, one writes continuously for a certain amount of time without editing or analyzing what comes out. Peter Elbrow originally created the technique ( also known as loop writing ) during the 1970s as a means to overcome writer’s block and help one’s ideas flow easily onto paper.

Freewriting is a technique developed by Peter Elbow that helps you achieve a state of controlled creativity by jotting down ideas on paper and then connecting those ideas (much like a mind map).

Writers in many different fields use freewriting as a strategy to improve their writing efficiency and overcome blocks. For instance, nurses may use freewriting to write reports, research papers, evaluate experiments, or map ideas for clinical improvement plans.

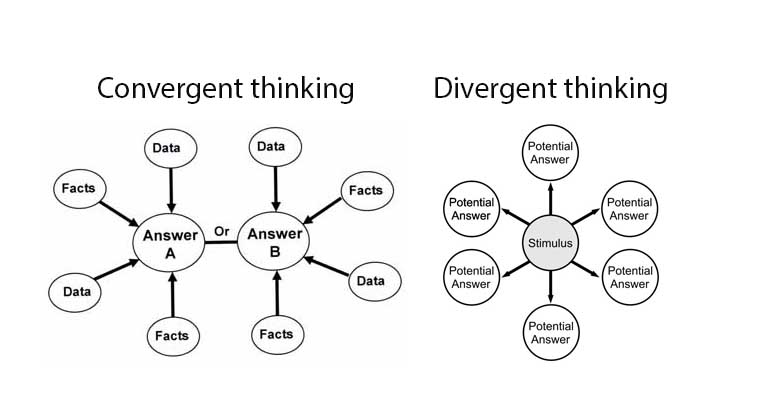

Either way, freewriting stimulates the part of your brain that is involved with divergent thinking , or thinking related to creative problem solving and ideas outside of the topic you are focused on.

Divergent thinking is a useful exercise for the freewriting process because it stimulates creativity.

Psychologists may use freewriting to clarify thoughts and feelings. Additionally, poets and artists often use freewriting as the first step in making their ideas tangible. Whatever your field of study, freewriting is an excellent tool that can assist professional and scholarly research.

What’s the purpose of freewriting?

This strategy of allowing ideas to continuously flow onto the paper without editing or analyzing theme is especially helpful when conducting a large amount of research. For instance, if you’re conducting a research project on current communication barriers and issues in current nursing practice ( click here to read a sample nursing paper), you may have read up to ten or fifteen articles about communication and nursing.

But, after reading these articles, what’s the next step ? This is where freewriting comes in.

During the process, you’ll allow yourself to write for, let’s say, 15 minutes, without stopping. During that time you’ll write down everything that comes to mind about what you’ve just read. The result is a stream of ideas and thoughts you’ve gathered from your research, that you can evaluate and organize later. The purpose is simply to put your thoughts down on paper about what you’ve just read.

After you have conducted your research, give yourself 15 minutes to jot down notes and ideas that come into your head. Don’t worry about organization or handwriting (just make sure it’s legible).

Finally, freewriting is important because the good ideas you will get will result an a final paper or essay that stands out from the crowd (because of your original thinking).

Freewriting as a form of mind mapping

Freewriting, therefore, is a kind of mind mapping, where you are allowed to visualize and brainstorm without thinking about order, structure, and the formalities of completed work.

Going through the process of freewriting and mind mapping will allow you to better organize your thoughts later during the research process.

Why is Freewriting Important?

Nothing’s more discouraging as a student, or a professional writer, than staring at a blank screen, searching for the right words. Many writers struggle with writer’s block. If you can identify, you’re not alone, and freewriting is an effective way to overcome writer’s block (like choosing to use paper writing services from Ultius ). It basically works by separating our writing process from our internal “critic,” so that we can write without over-analyzing our ideas, (which otherwise stops the writing flow).

Here are some other ways freewriting can assist the research process:

Besides being beneficial for your final written product, freewriting during research is a tactic that great writers use. Forgetting to freewrite during the research process is a mistake that professional essay writers never make .

When to use freewriting as part of your research process

Getting your ideas onto paper by letting them flow in a free-form method (freewriting) can be particularly helpful if you’re writing an exceptionally lengthy research paper (or an entire dissertation ), or embarking on an extensive research project.

It doesn’t matter what step you are in during the research process, freewriting can always help.

Carrying out a research process can be tricky, especially if the paper is longer.

Stuck with research? Consider buying your research proposal from an expert writer.

The more extensive and in-depth a project is, often the more difficult it can be to extract the topics and themes you’d like to write about, let alone organize and synthesize those ideas into an outline. In cases like this, freewriting acts as a catalyst to transfer your mental ideas to paper (or Google Docs ) so that you can see and rearrange them later in a way that makes sense to you.

Freewriting can also be incredibly beneficial if you’re having trouble understanding how different components of research relate to one another. Through the free-flow process, you’ll end up jotting down ideas that may seem unrelated at first. But, when you go back and re-read your freewriting, you’ll be able to more easily identify common themes.

Finally, freewriting can even be helpful when you’re further along in the research process. For instance, if you’ve already created an outline ( see an example of an outline ) but you’re struggling to “fill in the blanks,” so to speak, by writing the actual paragraphs of your paper, start by freewriting.

Simply freewrite any paragraph of the outline you’re struggling with, using the subtopic of the outline as your thought trigger and flow-writing guide. This will also help you overcome writer’s block. When you’re done, you’ll be able to go back and organize your freewriting into a paragraph that makes sense by omitting what doesn’t belong. Next, you’ll be able to edit and restructure what relates.

How to freewrite during the research process

Like any anything, the more one practices freewriting, the easier it becomes. The chart below outlines a basic step-by-step process, to get you started:

Keeping your hand moving (or your fingers typing), as mentioned in step five, is usually the most difficult step. However, it’s also the most important part, since it’s crucial in order to overcome writer’s block.

If you’re struggling to keep writing, think back to the thoughts that flooded your mind as you were reading your research. Even if you repeat a word or phrase, or write something that seems altogether unrelated to your research, that’s ok.

The purpose of freewriting isn’t to produce an organized discussion. Rather, it’s to subconsciously (and consciously) train your mind and hands to keep moving together to produce a free flow of ideas. The objective of freewriting is to remove any blocks (like fear and self-criticism) that inhibit the writing or research process .

Examples of freewriting (what it looks like)

Sometimes it’s helpful to see examples before starting a new process. If you’ve never freewritten before, seeing writing examples can provide a sense of permission and clarity about what freewriting may look like, which helps overcome self-doubt and fear, both of which hinder your free-flowing process.

The length of your freewriting will usually vary depending on how long you allow yourself to freewrite for. If you do a five-minute freewriting session, you may only have a paragraph or two of writing. If you freewrite for 15 or 20 minutes, you may have a few pages, depending on how fast you write.

There is no right or wrong length to freewriting. When you’re starting out, it’s sometimes easier to start with shorter freewriting sessions, which are generally less intimidating.

If you complete a short freewriting session, you’ll likely feel a sense of accomplishment. This will give you more confidence to embark on a longer session the next time. The longer you allow yourself to free write for, the more ideas that will likely emerge from the process.

Here’s a sample of what freewriting may look like, based on reading three research articles related to professional communication issues in nursing practice. Remember, in freewriting, nothing is edited, so it’s ok if there’s spelling and grammatical errors, or incomplete sentences in this stage of the process.

Freewriting session on communication in nursing research:

“Nurses feel silenced. Ethical challenges result from communication issues, some nurses don’t feel heard…patients need good communication to feel cared for…. Care communication care communication is essential to quality care, it’s important for everyone involved to understand what good communication means and its value. It’s also critical for ethical issues to be understood… patients need to be heard, it’s important to think about confidentiality so that communicating doesn’t breach bpra privacy patient privacy…. Education can help nurses communicate better. It’s not just nurses who need to be educated. It’s also patients and all stakeholders like administrators. A lot of studies have been done that have found better communication helps hospitals be more productive and efficient and have higher ratings. Nurses need to feel heard and appreciated to do their best work.”

1. Kourkouta, L., & Papathanasiou, I. V. (2014). Communication in Nursing Practice. Materia Socio-Medica, 26(1), 65–67. http://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2014.26.65-67 2. Norouzinia, R., Aghabarari, M., Shiri, M., Karimi, M., & Samami, E. (2016). Communication Barriers Perceived by Nurses and Patients. Global Journal of Health Science, 8(6), 65–74. http://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p65 3. Rushton, C. H., & Stutzer, K. (2015). Addressing 21st Century Nursing Ethics: Implications for Critical Care Nurses. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 26(2), 173–176. http://doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0000000000000083

As the example above shows, don’t worry about spelling, grammar, or structure. Just get the ideas out.

Bringing it all together—freewriting, research, outline, then writing

Now that you have seen what freewriting looks like, what’s next? Now it’s time to bring it all together by narrowing your important ideas down and moving them to your outline. The goal is, after all, to use freewriting to help with your research process.

It’s a good point to remember that not all of your freewriting thoughts are going to be useful for the next steps. That’s perfectly OK.

By following the steps provided in the brainstorming infographic, you will be well on your way to mastering the difficult research portion of your project. Additionally, when you are done with it you will clearly know what the purpose of freewriting is during the research process, and why it’s essential to do it.

Final tips on your freewriting experience before/after the research process

The above how-to steps of freewriting provide a great foundation for any writer looking to use freewriting to speed, improve, and clarify their research process. But, there are also a few extra tips that can help you get the most out of your freewriting process.

Check out the checklist below to maximize your success:

- 1. Define your topic: Having a clear vision of your research topic will not only guide you in reading the most related empirical articles, but it will also guide your freewriting process, so that the ideas naturally flowing from your mind onto the paper, connecting what you’ve read to your topic.

- 2. Notice what stands out: If you’re having trouble keeping your pen moving (or your fingers typing) during your timed freewriting session, keep directing your thoughts to what stood out to you from the research you conducted—even if you have to repeat ideas, that’s ok! Remember, the idea is to keep writing.

- 3. Let go of your critic: When it comes to writing, we all have a critic. And it’s important to remember that there’s a time and place for that critic (like when we’re proof reading our final draft). However, the critic is not our friend while we’re conducting the freewriting/research process, trying to overcome writer’s block. So, say goodbye to your internal critic. Don’t analyze. Just let your ideas flow, uninhibited.

- 4. Practice, practice, practice! Remember, it’s not always easy the first time, so if freewriting seems unnatural, or awkward, it’s ok. But, the more you do it, the more comfortable you’ll become with it. Plus, the more you’ll develop your own method that works most efficiently for you. Don’t worry if it’s not “perfect” the first time.

Finally, don’t be afraid to ask for help. Great writers all learn and gain inspiration from mentors, peers and instructors, at some point. If you’re feeling stuck and unsure of what steps to take next, help is as easy as a call, email, or text away. Ultius can help you with the freewriting process through our writing or editing services (by connecting you with a writer).

Thanks for reading and good luck!

https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/what-is-the-purpose-of-freewriting-during-the-research-process.html

- Chicago Style

Ultius, Inc. "What Is the Purpose of Freewriting During the Research Process?." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. Ultius Blog, 02 Nov. 2018. https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/what-is-the-purpose-of-freewriting-during-the-research-process.html

Copied to clipboard

Click here for more help with MLA citations.

Ultius, Inc. (2018, November 02). What Is the Purpose of Freewriting During the Research Process?. Retrieved from Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services, https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/what-is-the-purpose-of-freewriting-during-the-research-process.html

Click here for more help with APA citations.

Ultius, Inc. "What Is the Purpose of Freewriting During the Research Process?." Ultius | Custom Writing and Editing Services. November 02, 2018 https://www.ultius.com/ultius-blog/entry/what-is-the-purpose-of-freewriting-during-the-research-process.html.

Click here for more help with CMS citations.

Click here for more help with Turabian citations.

Ultius is the trusted provider of content solutions and matches customers with highly qualified writers for sample writing, academic editing, and business writing.

Tested Daily

Click to Verify

About The Author

This post was written by Ultius.

- Writer Options

- Custom Writing

- Business Documents

- Support Desk

- +1-800-405-2972

- Submit bug report

- A+ BBB Rating!

Ultius is the trusted provider of content solutions for consumers around the world. Connect with great American writers and get 24/7 support.

© 2024 Ultius, Inc.

- Refund & Cancellation Policy

Free Money For College!

Yeah. You read that right —We're giving away free scholarship money! Our next drawing will be held soon.

Our next winner will receive over $500 in funds. Funds can be used for tuition, books, housing, and/or other school expenses. Apply today for your chance to win!

* We will never share your email with third party advertisers or send you spam.

** By providing my email address, I am consenting to reasonable communications from Ultius regarding the promotion.

Past winner

- Name Samantha M.

- From Pepperdine University '22

- Studies Psychology

- Won $2,000.00

- Award SEED Scholarship

- Awarded Sep. 5, 2018

Thanks for filling that out.

Check your inbox for an email about the scholarship and how to apply.

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening

Brainstorming

“It is better to have enough ideas for some of them to be wrong, than to always be right by having no ideas at all.” —Edward de Bono

Most people have been taught how to brainstorm, but review these instructions to make sure you understand all aspects of it.

- Don’t write in complete sentences, just words and phrases, and don’t worry about grammar or even spelling;

- Again, do NOT judge or skip any idea, no matter how silly or crazy it may initially seem; you can decide later which ones are useful and which are not, but if you judge now, you may miss a great idea or connection;

- Do this for 15, 20, or (if you’re on a roll) even 30 minutes–basically until you think you have enough material to start organizing or, if needed, doing research.

Below is a sample brainstorm for an argument/research paper on the need for a defense shield around the earth:

Photo: “Brainstorm” ©2007 Jonathan Aguila

Account Options

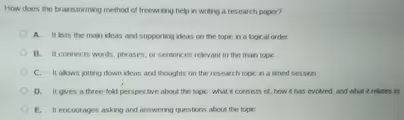

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? A. It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. B. It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. C. It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session. D. It gives a three-fold perspective about the topic: what it consists of, how it has evolved, and what it relates to E. It encourages asking and answering questions about the topic.

Gauth ai solution, super gauth ai.

Freewriting helps in writing a research paper by allowing the writer to jot down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session and encouraging asking and answering questions about the topic

Explanation

The brainstorming method of freewriting helps in writing a research paper by: C. Allowing jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session E. Encouraging asking and answering questions about the topic

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Freewriting, a writing strategy developed by Peter Elbow in 1973, is similar to brainstorming but is written in sentence and paragraph form without stopping. ... DO keep going for 15 or 20 minutes or until you feel you have enough to start to build your paper or research on. NOTE: In Peter Elbow's original formulation of freewriting, designed ...

Freewriting. Freewriting, a term coined by writing teacher Peter Elbow in the 1970s, is similar to brainstorming but is done in sentence and paragraph form and thus increases the flow of ideas and reduces the chance that you'll accidentally censor a good idea: Do NOT judge or skip any idea or word that comes to your mind, no matter if it is ...

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? ... Lennox is doing Internet research for a paper about cell phone use while driving. Lennox wants to prove that driving while using a cell phone is dangerous. ... Jodie is writing a report on health insurance in the United States. As a reference, she's using an ...

How to do it: Take your sheet (s) of paper and write your main topic in the center, using a word or two or three. Moving out from the center and filling in the open space any way you are driven to fill it, start to write down, fast, as many related concepts or terms as you can associate with the central topic.

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? a.) It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. b.) It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. c.) It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session. d.)

Brainstorming. Brainstorming allows you to quickly generate a large number of ideas. You can brainstorm with others or you can brainstorm by yourself, which sometimes turns into freewriting. To effectively brainstorm, write down whatever ideas come to mind. The key is to not place judgment on what you wrote.

We often call these prewriting strategies "brainstorming techniques.". Five useful strategies are listing, clustering, freewriting, looping, and asking the six journalists' questions. These strategies help you with both your invention and organization of ideas, and they can aid you in developing topics for your writing.

a technique for generating ideas for a piece of writing; it involves writing anything that comes to mind for a set period of time. "blank-page jitters". if you write on a computer, try prewriting in different ways: on paper and on the computer. Some writers feel they produce better work if they prewrite by hand and only later transfer their ...

30 people found it helpful. profile. deniserobyn. brainstorming helps you figure out the things you want to write. It also helps you figure out what order you want to put it in. Advertisement.

Freewriting is a technique developed by Peter Elbow that helps you achieve a state of controlled creativity by jotting down ideas on paper and then connecting those ideas (much like a mind map). Writers in many different fields use freewriting as a strategy to improve their writing efficiency and overcome blocks.

Most people have been taught how to brainstorm, but review these instructions to make sure you understand all aspects of it. Make a list (or list s) of every idea you can think of about your subject; Don't write in complete sentences, just words and phrases, and don't worry about grammar or even spelling;

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session.

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? 1 It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. 2 It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. 3 It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session. 4 It gives a three-fold ...

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? APA style and resources are also addressed. You may have heard teachers refer to this stage as pre-writing.

Find step-by-step solutions and your answer to the following textbook question: How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? a) It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. b) It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. c) It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed ...

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? A. It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. B. It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. C. It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session. D.

Answer. Brainstorming is thinking of idea's and organizing them into subtopics. This can help organize the research paper so that you know what you're ready to write about. Without the brainstorming method, you'll wander into other topics and might forget what you think is crucial to inform the readers about.

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? 1 It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. 2 It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. 3 It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session.

How does the brainstorming method of freewriting help in writing a research paper? A. It lists the main ideas and supporting ideas on the topic in a logical order. B. It connects words, phrases, or sentences relevant to the main topic. C. It allows jotting down ideas and thoughts on the research topic in a timed session. D.