- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

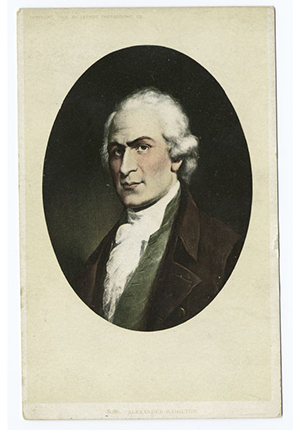

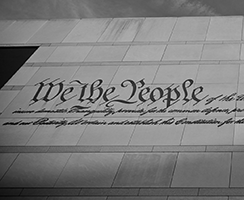

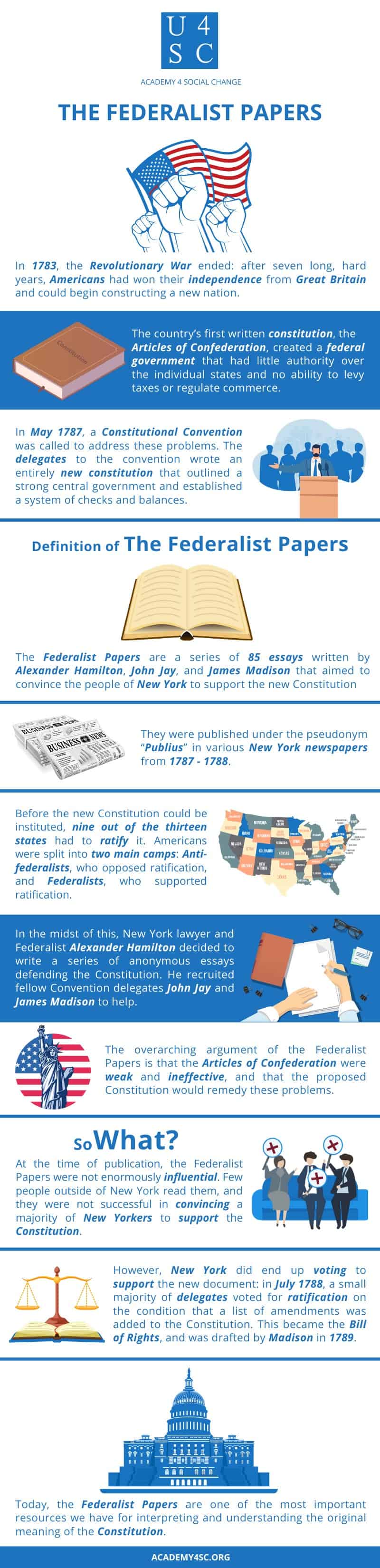

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

How Did Magna Carta Influence the U.S. Constitution?

The 13th‑century pact inspired the U.S. Founding Fathers as they wrote the documents that would shape the nation.

The Founding Fathers Feared Political Factions Would Tear the Nation Apart

The Constitution's framers viewed political parties as a necessary evil.

Checks and Balances

Separation of Powers The idea that a just and fair government must divide power between various branches did not originate at the Constitutional Convention, but has deep philosophical and historical roots. In his analysis of the government of Ancient Rome, the Greek statesman and historian Polybius identified it as a “mixed” regime with three branches: […]

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

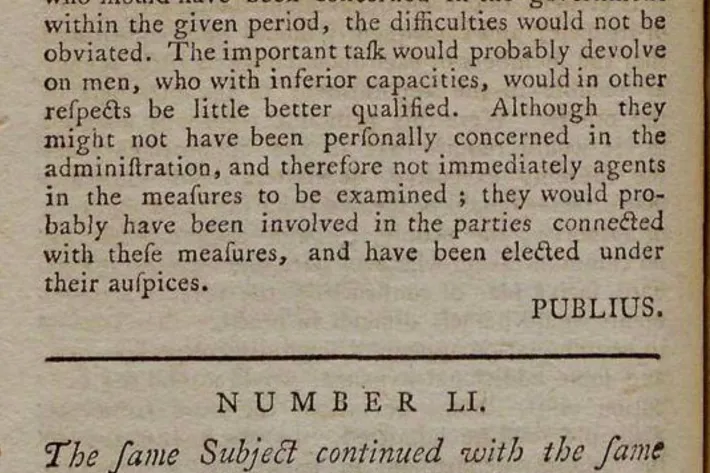

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What did James Madison accomplish?

- What was Alexander Hamilton’s early life like?

- Why is Alexander Hamilton famous?

Federalist papers

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Khan Academy - The Federalist Papers

- Digital History - Federalist Papers

- Online Library of Liberty - Quentin Taylor, “The Federalist Papers: America’s Political Classic”

- Teach Democracy - The Federalist Papers

- Social Science LibreTexts - Federalist Papers #10 and #51

- CORE - The Federalist Papers and the Constitution of the United States

- Library of Congress Research Guides - Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History

- Yale Law School - Lillian Goldman Law Library - The Avalon Project - The Federalist Papers

- University of Wisconsin–Madison - Center for the Study of the American Constitution - The Federalist Papers

- Federalist Papers - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Federalist papers - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Federalist papers , series of 85 essays on the proposed new Constitution of the United States and on the nature of republican government , published between 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay in an effort to persuade New York state voters to support ratification. Seventy-seven of the essays first appeared serially in New York newspapers, were reprinted in most other states, and were published in book form as The Federalist on May 28, 1788; the remaining eight essays appeared in New York newspapers between June 14 and August 16, 1788.

All the papers appeared over the signature “Publius,” and the authorship of some of the papers was once a matter of scholarly dispute . However, computer analysis and historical evidence has led nearly all historians to assign authorship in the following manner: Hamilton wrote numbers 1, 6–9, 11–13, 15–17, 21–36, 59–61, and 65–85; Madison , numbers 10, 14, 18–20, 37–58, and 62–63; and Jay, numbers 2–5 and 64.

The authors of the Federalist papers presented a masterly defense of the new federal system and of the major departments in the proposed central government. They also argued that the existing government under the Articles of Confederation , the country’s first constitution, was defective and that the proposed Constitution would remedy its weaknesses without endangering the liberties of the people.

As a general treatise on republican government, the Federalist papers are distinguished for their comprehensive analysis of the means by which the ideals of justice , the general welfare , and the rights of individuals could be realized. The authors assumed that people’s primary political motive is self-interest and that people—whether acting individually or collectively—are selfish and only imperfectly rational. The establishment of a republican form of government would not of itself provide protection against such characteristics: the representatives of the people might betray their trust; one segment of the population might oppress another; and both the representatives and the public might give way to passion or caprice . The possibility of good government, they argued, lay in the crafting of political institutions that would compensate for deficiencies in both reason and virtue in the ordinary conduct of politics. This theme was predominant in late 18th-century political thought in America and accounts in part for the elaborate system of checks and balances that was devised in the Constitution.

The authors of the Federalist papers argued against the decentralization of political authority under the Articles of Confederation. They worried, for example, that national commercial interests suffered from intransigent economic conflicts between states and that federal weakness undermined American diplomatic efforts abroad. Broadly, they argued that the government’s impotence under the Articles of Confederation obstructed America’s emergence as a powerful commercial empire.

The authors were also critical of the power assumed by state legislatures under the Articles of Confederation—and of the characters of the people serving in those assemblies. In the authors’ view, the farmers and artisans who rose to power in postrevolutionary America were too beholden to narrow economic and regional interests to serve the broader public good. Of particular concern to the authors was the passage by state legislatures of pro-debtor legislation and paper money laws that threatened creditors’ property rights . Unlike most Americans of the period, who typically worried about the conspiracies of the elite few against the liberties of the people, the authors were concerned about tyrannical legislative majorities threatening the rights of propertied minorities. The Articles of Confederation, in their view, had provided no safeguards against the vices of the people themselves, and the American Revolution’s enthusiasm for liberty had diminished popular appreciation of the need for good governance. The Federalist papers presented the 1786–87 insurrection of debtor farmers in western Massachusetts— Shays’s Rebellion —as a symptom of this broader crisis.

The authors of the Federalist papers argued for an increase in the “energy” of the federal government to respond to this crisis. However, the national government’s increased power would have to be based in republican principles and retain a federal distribution of power; there would be no return to monarchical rule or consolidation of central authority.

In one of the most notable essays, “Federalist 10,” Madison rejected the then common belief that republican government was possible only for small states. He argued that stability, liberty, and justice were more likely to be achieved in a large area with a numerous and heterogeneous population. Although frequently interpreted as an attack on majority rule, the essay is in reality a defense of both social, economic, and cultural pluralism and of a composite majority formed by compromise and conciliation. Decision by such a majority, rather than by a monistic one, would be more likely to accord with the proper ends of government. This distinction between a proper and an improper majority typifies the fundamental philosophy of the Federalist papers; republican institutions, including the principle of majority rule, were not considered good in themselves but were good because they constituted the best means for the pursuit of justice and the preservation of liberty.

The Federalist Papers

Appearing in New York newspapers as the New York Ratification Convention met in Poughkeepsie, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison wrote as Publius and addressed the citizens of New York through the Federalist Papers. These essays subsequently circulated and were reprinted throughout the states as the Ratification process unfolded in other states. Initially appearing as individual items in several New York newspapers, all eighty-five essays were eventually combined and published as The Federalist . Click here to view a chronology of the Printing and Reprintings of The Federalist .

Considerable debate has surrounded these essays since their publication. Many suggest they represent the best exposition of the Constitution to date. Their conceptual design would affirm this view. Others contend that they were mere propaganda to allay fears of the opposition to the Constitution. Regardless, they are often included in the canon of the world’s great political writings. A complete introduction exploring the purpose, authorship, circulation, and reactions to The Federalist can be found here.

General Introduction

- No. 1 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 27 October 1787

Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence

- No. 2 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 31 October 1787

- No. 3 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 3 November 1787

- No. 4 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 7 November 1787

- No. 5 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 10 November 1787

Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States

- No. 6 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 14 November 1787

- No. 7 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 17 November 1787

- No. 8 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 20 November 1787

- No. 9 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 21 November 1787

The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection

- No. 10 (Madison) New York Daily Advertiser , 22 November 1787

The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy

- No. 11 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 24 November 1787

The Utility of the Union in Respect to Revenue

- No. 12 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 27 November 1787

Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government

- No. 13 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 28 November 1787

Objections to the Proposed Constitution from Extent of Territory Answered

- No. 14 (Madison) New York Packet , 30 November 1787

The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union

- No. 15 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 1 December 1787

- No. 16 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 4 December 1787

- No. 17 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 5 December 1787

- No. 18 (Madison with Hamilton) New York Packet , 7 December 1787

- No. 19 (Madison with Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 8 December 1787

- No. 20 (Madison with Hamilton) New York Packet , 11 December 1787

- No. 21 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 12 December 1787

- No. 22 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 14 December 1787

The Necessity of Energetic Government to Preserve of the Union

- No. 23 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 18 December 1787

Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered

- No. 24 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 19 December 1787

- No. 25 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 21 December 1787

Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense

- No. 26 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 22 December 1787

- No. 27 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 25 December 1787

- No. 28 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 26 December 1787

Concerning the Militia

- No. 29 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 9 January 1788

Concerning the General Power of Taxation

- No. 30 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 28 December 1787

- No. 31 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 1 January 1788

- Nos. 32–33 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 2 January 1788

- No. 34 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 4 January 1788

- No. 35 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 5 January 1788

- No. 36 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 8 January 1788

The Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government

- No. 37 (Madison) New York Daily Advertiser , 11 January 1788

- No. 38 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 12 January 1788

The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles

- No. 39 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 16 January 1788

The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined

- No. 40 (Madison) New York Packet , 18 January 1788

General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution

- No. 41 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 19 January 1788

- No. 42 (Madison) New York Packet , 22 January 1788

- No. 43 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 23 January 1788

Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States

- No. 44 (Madison) New York Packet , 25 January 1788

Alleged Danger from the Powers of the Union to the State Governments

- No. 45 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 26 January 1788

Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared

- No. 46 (Madison) New York Packet , 29 January 1788

Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Powers

- No. 47 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 30 January 1788

Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated

- No. 48 (Madison) New York Packet , 1 February 1788

Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government

- No. 49 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 2 February 1788

Periodic Appeals to the People Considered

- No. 50 (Madison) New York Packet , 5 February 1788

Structure of Government Must Furnish Proper Checks and Balances

- No. 51 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 6 February 1788

The House of Representatives

- No. 52 (Madison?) New York Packet , 8 February 1788

- No. 53 (Madison or Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 9 February 1788

The Apportionment of Members Among the States

- No. 54 (Madison) New York Packet , 12 February 1788

The Total Number of the House of Representatives

- No. 55 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 13 February 1788

- No. 56 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 16 February 1788

The Alleged Tendency of the Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many

- No. 57 (Madison?) New York Packet , 19 February 1788

Objection That the Numbers Will Not Be Augmented as Population Increases

- No. 58 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 20 February 1788

Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members

- No. 59 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 22 February 1788

- No. 60 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 23 February 1788

- No. 61 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 26 February 1788

- No. 62 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 27 February 1788

- No. 63 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 1 March 1788

- No. 64 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 5 March 1788

- No. 65 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 7 March 1788

Objections to the Power of the Senate to Set as a Court for Impeachments

- No. 66 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 8 March 1788

The Executive Department

- No. 67 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 11 March 1788

The Mode of Electing the President

- No. 68 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 12 March 1788

The Real Character of the Executive

- No. 69 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 14 March 1788

The Executive Department Further Considered

- No. 70 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 15 March 1788

The Duration in Office of the Executive

- No. 71 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 18 March 1788

Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered

- No. 72 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 19 March 1788

Provision for The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power

- No. 73 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 21 March 1788

The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power

- No. 74 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 25 March 1788

The Treaty Making Power of the Executive

- No. 75 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 26 March 1788

The Appointing Power of the Executive

- No. 76 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 1 April 1788

Appointing Power and Other Powers of the Executive Considered

- No. 77 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 2 April 1788

The Judiciary Department

- No. 78 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

- No. 79 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Powers of the Judiciary

- No. 80 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority

- No. 81 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Judiciary Continued

- No. 82 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury

- No. 83 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered

- No. 84 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

Concluding Remarks

- No. 85 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Federalist Papers (1787-1788)

Federalist papers.

After the Constitution was completed during the summer of 1787, the work of ratifying it (or approving it) began. As the Constitution itself required, 3/4ths of the states would have to approve the new Constitution before it would go into effect for those ratifying states.

The Constitution granted the national government more power than under the Articles of Confederation . Many Americans were concerned that the national government with its new powers, as well as the new division of power between the central and state governments, would threaten liberty.

What are the Federalist Papers?

In order to help convince their fellow Americans of their view that the Constitution would not threaten freedom, Federalist Paper authors, James Madison , Alexander Hamilton , and John Jay teamed up in 1788 to write a series of essays in defense of the Constitution. The essays, which appeared in newspapers addressed to the people of the state of New York, are known as the Federalist Papers. They are regarded as one of the most authoritative sources on the meaning of the Constitution, including constitutional principles such as checks and balances, federalism, and separation of powers.

Federalist Papers Collection

Federalist and anti-federalist playlist.

Related Resources

Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Federalist or Anti-Federalist? Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. We look forward to exploring this important debate with you! One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification […]

Federalist No. 1 Excerpts Annotated

Federalist 10

Written by James Madison, this essay defended the form of republican government proposed by the Constitution. Critics of the Constitution argued that the proposed federal government was too large and would be unresponsive to the people.

Primary Source: Federalist No. 26

Primary Source: Federalist No. 33

Handout E: Excerpts from Federalist No. 39, James Madison (1788)

Primary Source: Excerpts from Federalist No. 44

Handout B: Excerpts from Federalist No 10, 51, 55, and 57

Handout I: Excerpts of Federalist No. 57

Primary Source: Federalist No. 39

Primary Source: Madison – Excerpts from Federalist No. 47 (1788)

Federalist 51

In this Federalist Paper, James Madison explains and defends the checks and balances system in the Constitution. Each branch of government is framed so that its power checks the power of the other two branches; additionally, each branch of government is dependent on the people, who are the source of legitimate authority.

Handout A: Excerpts from Federalist No 62

Primary Source: Excerpts from Federalist No. 63

Federalist 70

In this Federalist Paper, Alexander Hamilton argues for a strong executive leader, as provided for by the Constitution, as opposed to the weak executive under the Articles of Confederation. He asserts, “energy in the executive is the leading character in the definition of good government.

Primary Source: Federalist No. 78 Excerpts Annotated

Primary Source: Federalist No. 84 Excerpts Annotated

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

- Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

- Election Teaching Resources

Constitution 101 With Khan Academy

Explore our new course that empowers students to learn the constitution at their own pace..

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, federalist 1 (1787).

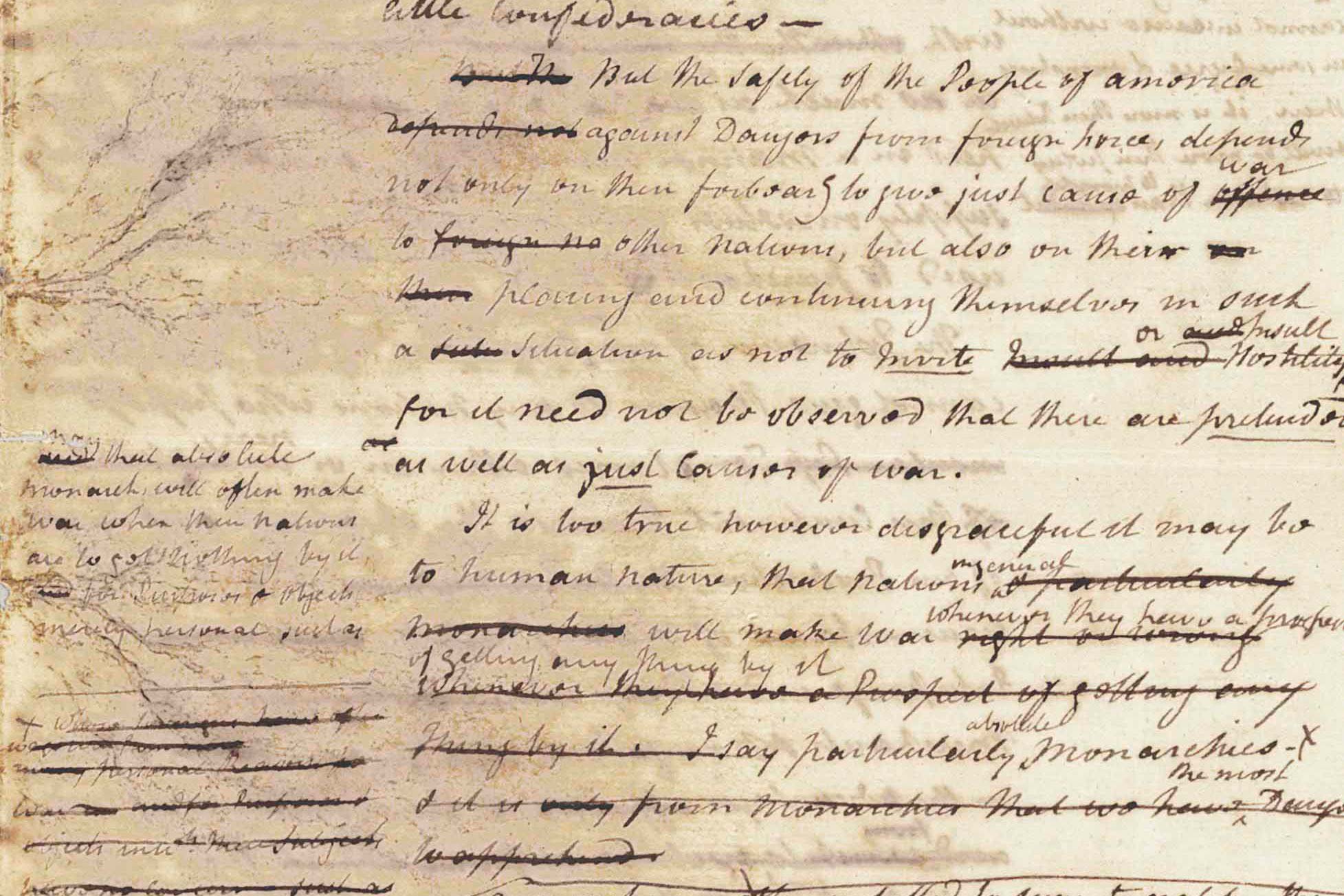

Alexander Hamilton | 1787

On October 27, 1787, Alexander Hamilton published the opening essay of The Federalist Papers — Federalist 1 . The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays printed in newspapers to persuade the American people (and especially Hamilton’s fellow New Yorkers) to support ratification of the new Constitution. These essays were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay—with all three authors writing under the pen name “Publius.” On September 17, 1787, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had signed the new U.S. Constitution. This new Constitution was the Framers’ proposal for a new national government. But it was only that—a proposal. The Framers left the question of ratification—whether to say “yes” or “no” to the new Constitution—to the American people. In the Framers’ view, only the American people themselves had the authority to tear up the previous framework of government—the Articles of Confederation—and establish a new one. The ratification process itself embodied one of the Constitution’s core principles: popular sovereignty, or the idea that all political power is derived from the consent of “We the People.” In Federalist 1, Hamilton captured this vision well, framing the stakes of the battle over ratification. In this opening essay, Hamilton called on the American people to “deliberate on a new Constitution” and prove to the world that they were capable of choosing a government based on “reflection and choice,” not “accident and force.”

Selected by

The National Constitution Center

AFTER an unequivocal experience of the inefficiency of the subsisting federal government, you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution for the United States of America. The subject speaks its own importance; comprehending in its consequences nothing less than the existence of the UNION, the safety and welfare of the parts of which it is composed, the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind. This idea will add the inducements of philanthropy to those of patriotism, to heighten the solicitude which all considerate and good men must feel for the event. Happy will it be if our choice should be directed by a judicious estimate of our true interests, unperplexed and unbiased by considerations not connected with the public good. But this is a thing more ardently to be wished than seriously to be expected. The plan offered to our deliberations affects too many particular interests, innovates upon too many local institutions, not to involve in its discussion a variety of objects foreign to its merits, and of views, passions and prejudices little favorable to the discovery of truth.

Among the most formidable of the obstacles which the new Constitution will have to encounter may readily be distinguished the obvious interest of a certain class of men in every State to resist all changes which may hazard a diminution of the power, emolument, and consequence of the offices they hold under the State establishments; and the perverted ambition of another class of men, who will either hope to aggrandize themselves by the confusions of their country, or will flatter themselves with fairer prospects of elevation from the subdivision of the empire into several partial confederacies than from its union under one government.

It is not, however, my design to dwell upon observations of this nature. I am well aware that it would be disingenuous to resolve indiscriminately the opposition of any set of men (merely because their situations might subject them to suspicion) into interested or ambitious views. Candor will oblige us to admit that even such men may be actuated by upright intentions; and it cannot be doubted that much of the opposition which has made its appearance, or may hereafter make its appearance, will spring from sources, blameless at least, if not respectable—the honest errors of minds led astray by preconceived jealousies and fears. So numerous indeed and so powerful are the causes which serve to give a false bias to the judgment, that we, upon many occasions, see wise and good men on the wrong as well as on the right side of questions of the first magnitude to society. This circumstance, if duly attended to, would furnish a lesson of moderation to those who are ever so much persuaded of their being in the right in any controversy. And a further reason for caution, in this respect, might be drawn from the reflection that we are not always sure that those who advocate the truth are influenced by purer principles than their antagonists. Ambition, avarice, personal animosity, party opposition, and many other motives not more laudable than these, are apt to operate as well upon those who support as those who oppose the right side of a question. Were there not even these inducements to moderation, nothing could be more ill-judged than that intolerant spirit which has, at all times, characterized political parties. For in politics, as in religion, it is equally absurd to aim at making proselytes by fire and sword. Heresies in either can rarely be cured by persecution.

And yet, however just these sentiments will be allowed to be, we have already sufficient indications that it will happen in this as in all former cases of great national discussion. A torrent of angry and malignant passions will be let loose. To judge from the conduct of the opposite parties, we shall be led to conclude that they will mutually hope to evince the justness of their opinions, and to increase the number of their converts by the loudness of their declamations and the bitterness of their invectives. An enlightened zeal for the energy and efficiency of government will be stigmatized as the offspring of a temper fond of despotic power and hostile to the principles of liberty. An over-scrupulous jealousy of danger to the rights of the people, which is more commonly the fault of the head than of the heart, will be represented as mere pretense and artifice, the stale bait for popularity at the expense of the public good. It will be forgotten, on the one hand, that jealousy is the usual concomitant of love, and that the noble enthusiasm of liberty is apt to be infected with a spirit of narrow and illiberal distrust. On the other hand, it will be equally forgotten that the vigor of government is essential to the security of liberty; that, in the contemplation of a sound and well-informed judgment, their interest can never be separated; and that a dangerous ambition more often lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people than under the forbidden appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government. History will teach us that the former has been found a much more certain road to the introduction of despotism than the latter, and that of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants. . . .

It may perhaps be thought superfluous to offer arguments to prove the utility of the UNION, a point, no doubt, deeply engraved on the hearts of the great body of the people in every State, and one, which it may be imagined, has no adversaries. But the fact is, that we already hear it whispered in the private circles of those who oppose the new Constitution, that the thirteen States are of too great extent for any general system, and that we must of necessity resort to separate confederacies of distinct portions of the whole. This doctrine will, in all probability, be gradually propagated, till it has votaries enough to countenance an open avowal of it. For nothing can be more evident, to those who are able to take an enlarged view of the subject, than the alternative of an adoption of the new Constitution or a dismemberment of the Union. It will therefore be of use to begin by examining the advantages of that Union, the certain evils, and the probable dangers, to which every State will be exposed from its dissolution. This shall accordingly constitute the subject of my next address.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

Federalist No. 51, 1788

The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, 1788 (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

The Federalist , often called The Federalist Papers, is a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison between October 1787 and May 1788. The essays were published anonymously, under the pen name “Publius,” primarily in two New York State newspapers: the New York Packet and the Independent Journal . The main purpose of the series was to urge the citizens of New York to support ratification of the proposed US Constitution. Significantly, the essays explain particular provisions of the Constitution in detail. It is for this reason, and because Hamilton and Madison were members of the Constitutional Convention, that the Federalist Papers are often used to help modern readers understand the intentions of those who drafted the Constitution. Federalist No. 51 was written by James Madison and published in February 1788. This essay addresses the need for checks and balances and advocates a separation of powers, suggesting that the government be divided into separate branches.

Federalist No. 51, February 8, 1788

The same Subject continued with the same View, and concluded

TO WHAT expedient, then, shall we finally resort for maintaining in practice the necessary partition of power among the several departments, as laid down in the constitution? The only answer that can be given is, that as all these exterior provisions are found to be inadequate, the defect must be supplied, by so contriving the interior structure of the government as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places. Without presuming to undertake a full development of this important idea, I will hazard a few general observations, which may perhaps place it in a clearer light, and enable us to form a more correct judgment of the principles and structure of the government planned by the convention.

In order to lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent, is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty, it is evident that each department should have a will of its own; and consequently should be so constituted that the members of each should have as little agency as possible in the appointment of the members of the others. Were this principle rigorously adhered to, it would require that all the appointments for the supreme executive, legislative, and judiciary magistracies should be drawn from the same fountain of authority, the people, through channels, having no communication whatever with one another. Perhaps such a plan of constructing the several departments would be less difficult in practice than it may in contemplation appear. Some difficulties, however, and some additional expense would attend the execution of it. Some deviations, therefore from the principle must be admitted. In the constitution of the judiciary department in particular, it might be inexpedient to insist rigorously on the principle; first, because peculiar qualifications being essential in the members, the primary consideration ought to be to select that mode of choice, which best secures these qualifications; secondly, because the permanent tenure by which the appointments are held in that department, must soon destroy all sense of dependence on the authority conferring them.

It is equally evident that the members of each department should be as little dependent as possible on those of the others, for the emoluments annexed to their offices. Were the executive magistrate, or the judges, not independent of the legislature in this particular, their independence in every other, would be merely nominal. But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department, the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions. This policy of supplying by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power; where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the State. But it is not possible to give to each department an equal power of self-defense. In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates. The remedy for this inconveniency is, to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them by different modes of election and different principles of action, as little connected with each other, as the nature of their common functions, and their common dependence on the society, will admit. It may even be necessary to guard against dangerous encroachments by still further precautions. As the weight of the legislative authority requires that it should be thus divided, the weakness of the executive may require, on the other hand, that it should be fortified.

An absolute negative, on the legislature, appears at first view to be the natural defense with which the executive magistrate should be armed. But perhaps it would be neither altogether safe, nor alone sufficient. On ordinary occasions, it might not be exerted with the requisite firmness; and on extraordinary occasions it might be perfidiously abused. May not this defect of an absolute negative be supplied by some qualified connection between this weaker department, and the weaker branch of the stronger department, by which the latter may be led to support the constitutional rights of the former, without being too much detached from the rights of its own department? If the principles on which these observations are founded be just, as I persuade myself they are, and they be applied as a criterion to the several state constitutions, and to the federal constitution it will be found that if the latter does not perfectly correspond with them, the former are infinitely less able to bear such a test.

There are, moreover, two considerations particularly applicable to the federal system of America, which place that system in a very interesting point of view. First. In a single republic, all the power surrendered by the people, is submitted to the administration of a single government; and the usurpations are guarded against by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments. In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself. Second. It is of great importance in a republic, not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers; but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part. Different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens. If a majority be united by a common interest, the rights of the minority will be insecure.

There are but two methods of providing against this evil: The one by creating a will in the community independent of the majority, that is, of the society itself; the other, by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens, as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole very improbable, if not impracticable. The first method prevails in all governments possessing an hereditary or self-appointed authority. This at best is but a precarious security; because a power independent of the society may as well espouse the unjust views of the major, as the rightful interests of the minor party, and may possibly be turned against both parties. The second method will be exemplified in the federal republic of the United States. Whilst all authority in it will be derived from, and dependent on the society, the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.

In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other, in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government. This view of the subject must particularly recommend a proper federal system to all the sincere and considerate friends of republican government; Since it shows that in exact proportion as the territory of the union may be formed into more circumscribed confederacies, or states, oppressive combinations of a majority will be facilitated, the best security under the republican forms, for the rights of every class of citizens, will be diminished; and consequently, the stability and independence of some member of the government, the only other security must be proportionately increased. Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been, and ever will be pursued, until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign, as in a state of nature where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger; And as in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves; so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradually induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful.

It can be little doubted that if the State of Rhode Island was separated from the confederacy, and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits, would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities, that some power altogether independent of the people would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good: Whilst there being thus less danger to a minor from the will of a major party, there must be less pretext, also, to provide for the security of the former, by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the latter; or in other words, a will independent of the society itself. It is no less certain than it is important, notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained, that the larger the society, provided it lie within a practicable sphere, the more duly capable it will be of self-government. And happily for the republican cause, the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the federal principle.

Source: James Madison, “Federalist No. 51,” The Federalist , New York, 1788, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC01551.

Plan Your Visit

- Things to Do

- Where to Eat

- Hours & Directions

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility

- Washington, D.C. Metro Area

- Guest Policies

- Historic Area

- Distillery & Gristmill

- Virtual Tour

George Washington

- French & Indian War

- Revolutionary War

- Constitution

- First President

- Martha Washington

- Native Americans

Preservation

- Collections

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association

- Restoration Projects

- Preserving the View

- Preservation Timeline

- For Teachers

- Primary Source Collections

- Secondary Sources

- Educational Events

- Interactive Tools

- Videos and Podcasts

- Hands on History at Home

Washington Library

- Catalogs and Digital Resources

- Research Fellowships

- The Papers of George Washington

- Library Events & Programs

- Leadership Institute

- Center for Digital History

- George Washington Prize

- About the Library

- Back to Main menu

- Colonial Music Institute

- Past Projects

- Digital Exhibits

- Digital Encyclopedia

- About the Encyclopedia

- Contributors

- George Washington Presidential Library

Estate Hours

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

u_turn_left Directions & Parking

Federalist Papers

George Washington was sent draft versions of the first seven essays on November 18, 1787 by James Madison, who revealed to Washington that he was one of the anonymous writers. Washington agreed to secretly transmit the drafts to his in-law David Stuart in Richmond, Virginia so the essays could be more widely published and distributed. Washington explained in a letter to David Humphreys that the ratification of the Constitution would depend heavily "on literary abilities, & the recommendation of it by good pens," and his efforts to proliferate the Federalist Papers reflected this feeling. 1

Washington was skeptical of Constitutional opponents, known as Anti-Federalists, believing that they were either misguided or seeking personal gain. He believed strongly in the goals of the Constitution and saw The Federalist Papers and similar publications as crucial to the process of bolstering support for its ratification. Washington described such publications as "have thrown new lights upon the science of Government, they have given the rights of man a full and fair discussion, and have explained them in so clear and forcible a manner as cannot fail to make a lasting impression upon those who read the best publications of the subject, and particularly the pieces under the signature of Publius." 2

Although Washington made few direct contributions to the text of the new Constitution and never officially joined the Federalist Party, he profoundly supported the philosophy behind the Constitution and was an ardent supporter of its ratification.

The philosophical influence of the Enlightenment factored significantly in the essays, as the writers sought to establish a balance between centralized political power and individual liberty. Although the writers sought to build support for the Constitution, Madison, Hamilton, and Jay did not see their work as a treatise, per se, but rather as an on-going attempt to make sense of a new form of government.

The Federalist Paper s represented only one facet in an on-going debate about what the newly forming government in America should look like and how it would govern. Although it is uncertain precisely how much The Federalist Papers affected the ratification of the Constitution, they were considered by many at the time—and continue to be considered—one of the greatest works of American political philosophy.

Adam Meehan The University of Arizona

Notes: 1. "George Washington to David Humphreys, 10 October 1787," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 657.

2. "George Washington to John Armstrong, 25 April 1788," in George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel (New York: Library of America, 1997), 672.

Bibliography: Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life . New York: Penguin, 2010.

Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of The Federalist . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Furtwangler, Albert. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984.

George Washington, Writings , ed. John Rhodehamel. New York: Library of America, 1997.

U.S. Constitution.net

Federalist papers and the constitution.

During the late 1780s, the United States faced significant challenges with its initial governing framework, the Articles of Confederation. These issues prompted the creation of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays aimed at advocating for a stronger central government under the newly proposed Constitution. This article will examine the purpose, key arguments, and lasting impact of these influential writings.

Background and Purpose of the Federalist Papers

The Articles of Confederation, though a pioneer effort, left Congress without the power to tax or regulate interstate commerce, making it difficult to pay off Revolutionary War debts and curb internal squabbles among states.

In May 1787, America's brightest political minds convened in Philadelphia and created the Constitution—a document establishing a robust central government with legislative, executive, and judicial branches. However, before it could take effect, the Constitution needed ratification from nine of the thirteen states, facing opposition from critics known as Anti-Federalists.

The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay under the pseudonym "Publius," aimed to calm fears and win support for the Constitution. Hamilton initiated the project, recruiting Madison and Jay to contribute. Madison drafted substantial portions of the Constitution and provided detailed defenses, while Jay, despite health issues, also contributed essays.

The Federalist Papers systematically dismantled the opposition's arguments and explained the Constitution's provisions in detail. They gained national attention, were reprinted in newspapers across the country, and eventually collated into two volumes for broader distribution.

Hamilton emphasized the necessity of a central authority with the power to tax and enforce laws, citing specific failures under the Articles like the inability to generate revenue or maintain public order. Jay addressed the need for unity and the inadequacies of confederation in foreign diplomacy.

The Federalist Papers provided the framework needed to understand and eventually ratify the Constitution, remaining essential reading for anyone interested in the foundations of the American political system.

Key Arguments in the Federalist Papers

Among the key arguments presented in the Federalist Papers, three themes stand out:

- The need for a stronger central government

- The importance of checks and balances

- The dangers of factionalism

Federalist No. 23 , written by Alexander Hamilton, argued for a robust central government, citing the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton contended that empowering the central government with the means to enforce laws and collect taxes was essential for the Union's survival and prosperity.

In Federalist No. 51 , James Madison addressed the principle of checks and balances, arguing that the structure of the new government would prevent any single branch from usurping unrestrained power. Each branch—executive, legislative, and judicial—would have the means and motivation to check the power of the others, safeguarding liberty.

Federalist No. 10 , also by Madison, delved into the dangers posed by factions—groups united by a common interest adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the community. Madison acknowledged that factions are inherent within any free society and cannot be eliminated without destroying liberty. He argued that a well-constructed Union would break and control the violence of faction by filtering their influence through a large republic.

Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 brought the concept of judicial review to the forefront, establishing the judiciary as a guardian of the Constitution and essential for interpreting laws and checking the actions of the legislature and executive branches. 1

The Federalist Papers meticulously dismantled Anti-Federalist criticisms and showcased how the proposed system would create a stable and balanced government capable of both governing effectively and protecting individual rights. These essays remain seminal works for understanding the underpinnings of the United States Constitution and the brilliance of the Founding Fathers.

Analysis of Federalist 10 and Federalist 51

Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 are two of the most influential essays within the Federalist Papers, elucidating fundamental principles that continue to support the American political system. They were carefully crafted to address the concerns of Anti-Federalists who feared that the new Constitution might pave the way for tyranny and undermine individual liberties.

In Federalist 10 , James Madison addresses the inherent dangers posed by factions. He argues that a large republic is the best defense against their menace, as it becomes increasingly challenging for any single faction to dominate in a sprawling and diverse nation. The proposed Constitution provides a systemic safeguard against factionalism by implementing a representative form of government, where elected representatives act as a filtering mechanism.

Federalist 51 further elaborates on how the structure of the new government ensures the protection of individual rights through a system of checks and balances. Madison supports the division of government into three coequal branches, each equipped with sufficient autonomy and authority to check the others. He asserts that ambition must be made to counteract ambition, emphasizing that the self-interest of individuals within each branch would serve as a natural check on the others. 2

Madison also delves into the need for a bicameral legislature, comprising the House of Representatives and the Senate. This dual structure aims to balance the demands of the majority with the necessity of protecting minority rights, thereby preventing majoritarian tyranny.

Together, Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 form a comprehensive blueprint for a resilient and balanced government. Madison's insights address both the internal and external mechanisms necessary to guard against tyranny and preserve individual liberties. These essays speak to the enduring principles that have guided the American republic since its inception, proving the timeless wisdom of the Founding Fathers and the genius of the American Constitution.

Impact and Legacy of the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers had an immediate and profound impact on the ratification debates, particularly in New York, where opposition to the Constitution was fierce and vocal. Alexander Hamilton, a native of New York, understood the weight of these objections and recognized that New York's support was crucial for the Constitution's success, given the state's economic influence and strategic location. The essays were carefully crafted to address New Yorkers' specific concerns and to persuade undecided delegates.

The comprehensive detail and logical rigor of the Federalist Papers succeeded in swaying public opinion. They systematically addressed Anti-Federalist critiques, such as the fear that a strong central government would trample individual liberties. Hamilton, Madison, and Jay argued for the necessity of a powerful, yet balanced federal system, capable of uniting the states and ensuring both national security and economic stability.

In New York, the Federalist essays began appearing in newspapers in late 1787 and continued into 1788. Despite opposition, especially from influential Anti-Federalists like Governor George Clinton, the arguments laid out by "Publius" played a critical role in turning the tide. They provided Federalists with a potent arsenal of arguments to counter Anti-Federalists at the state's ratification convention. When the time came to vote, the persuasive power of the essays contributed significantly to New York's eventual decision to ratify the Constitution by a narrow margin.

The impact of the Federalist Papers extends far beyond New York. They influenced debates across the fledgling nation, helping to build momentum towards the required nine-state ratification. Their detailed exposition of the Constitution's provisions and the philosophic principles underlying them offered critical insights for citizens and delegates in other states. The essays became indispensable tools in the broader national dialogue about what kind of government the United States should have, guiding the country towards ratification.

The long-term significance of the Federalist Papers in American political thought and constitutional interpretation is substantial. Over the centuries, they have become foundational texts for understanding the intentions of the Framers. Jurists, scholars, and lawmakers have turned to these essays for guidance on interpreting the Constitution's provisions, shaping American constitutional law. Judges, including the justices of the Supreme Court, have frequently cited these essays in landmark rulings to elucidate the Framers' intent.

The Federalist Papers have profoundly influenced the development of American political theory, contributing to discussions about federalism, republicanism, and the balance between liberty and order. Madison's arguments in Federalist No. 10 have become keystones in the study of pluralism and the mechanisms by which diverse interests can coexist within a unified political system.

The essays laid the groundwork for ongoing debates about the role of the federal government, the balance of power among its branches, and the preservation of individual liberties. They provided intellectual support for later expansions of constitutional rights through amendments and judicial interpretations.

Their legacy also includes a robust defense of judicial review and the judiciary's role as a guardian of the Constitution. Hamilton's Federalist No. 78 provided a compelling argument for judicial independence, which has been a cornerstone in maintaining the rule of law and protecting constitutional principles against transient political pressures.

The Federalist Papers were crucial in the ratification of the Constitution, particularly in the contentious atmosphere of New York's debates. Their immediate effect was to facilitate the acceptance of the new governing framework. In the long term, their meticulously argued positions have provided a lasting blueprint for constitutional interpretation, influencing American political thought and practical governance for over two centuries. The essays stand as a testament to the foresight and philosophical acumen of the Founding Fathers, continuing to illuminate the enduring principles of the United States Constitution.

- History , History of United States

The Federalist Papers: In Defense of the Constitution

In 1783, the Revolutionary War ended: after seven long, hard years, Americans had won their independence from Great Britain and could begin constructing a new nation. This, however, proved to be no easy feat. The country’s first written constitution, the Articles of Confederation, created a federal government that had little authority over the individual states and no ability to levy taxes or regulate commerce. Many believed this government was inefficient and ineffective, and in May 1787 a Constitutional Convention was called to address these problems. Instead of simply editing the Articles, however, the delegates to the convention wrote an entirely new constitution that outlined a strong central government and established a system of checks and balances.

Explanation

Before this document could become the new constitution of the country, nine out of the thirteen states had to ratify, or approve, it. The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays that attempted to convince the people of New York to support the proposed Constitution.

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison that aimed to convince the people of New York to support the new Constitution. They were published under the pseudonym “Publius” in various New York newspapers from 1787 - 1788.

The History

Before the new Constitution could be instituted, nine out of the thirteen states had to ratify it. Americans were split into two main camps: Anti-federalists, who opposed ratification and worried that giving the federal government more power would make it susceptible to tyranny, and Federalists, who supported ratification. New York was a hub of anti-federalist sentiment: many Anti-federalists published articles in New York newspapers arguing that the proposed Constitution gave Congress too much power and would threaten American citizens’ hard-won freedoms.

In the midst of this, New York lawyer and Federalist Alexander Hamilton decided to write a series of anonymous essays defending the Constitution. He recruited fellow Convention delegates John Jay and James Madison to help. Plagued by rheumatism, John Jay wrote only five essays, while Madison penned 29 and Hamilton authored 51.

The overarching argument of the Federalist Papers is that the Articles of Confederation were weak and ineffective, and that the proposed Constitution would remedy these problems by creating a stronger federal government without threatening the rights and freedoms of American citizens.

The first group of essays explains that under the system set by the Articles, the federal government was too decentralized for America to be a strong international presence or effectively address internal rebellions. Subsequent sections defend the proposed Constitution, including a group of essays devoted to the importance of the federal government’s power to levy taxes. Another large portion of the essays provides a comprehensive overview of the new structure of government proposed by the Constitution, including the system of checks and balances.

Some of the essays are more famous than others. One of the most influential was Federalist 10, written by Madison, which argues against the idea that republican governments, or governments in which political authority comes from the people, can only be successful in small countries. Madison argues that, in fact, larger countries are more conducive to successful republican governments because they are more heterogeneous and better able to balance the competing interests of different factions. Another particularly famous essay, Federalist 51, details the importance of checks and balances, arguing that this system protects against tyranny similar to what Americans suffered at the hands of the British. “You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to control itself,” Madison wrote, explaining that since both individuals and governments are fallible and prone to mistakes, a government must have checks on its power.

At the time of publication, the Federalist Papers were not enormously influential. Few people outside of New York read them, and they were not successful in convincing a majority of New Yorkers to support the Constitution; the state sent more Anti-federalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention. However, New York did end up voting to support the new document: in July 1788, a small majority of delegates voted for ratification on the condition that a list of amendments detailing additional rights was added to the Constitution. This list became the Bill of Rights, and was drafted by Madison in 1789.

Today, the Federalist Papers are one of the most important resources we have for interpreting and understanding the original meaning of the Constitution. The essays provide a comprehensive explanation of the principles and structure of government laid out in the Constitution, and have been cited in Supreme Court cases for centuries. In 1803, for instance, the Supreme Court cited Federalist 78 in its decision in Marbury v Madison, which affirmed judicial review, or the power of federal courts to determine if a statute is unconstitutional. In the years since, the Court has cited the essays dozens of times in a variety of decisions, and it will undoubtedly continue to do so, demonstrating the importance of the Federalist Papers to the country today.

Think Further

- What are some other documents that were used to convince the American public of something during the Revolutionary War period? How do they compare to the Federalist Papers ?

- Why do you think the authors of the Federalist Papers used a pseudonym?

- How might the country look different today if the Constitution had not been ratified?

Teacher Resources

Sign up for our educators newsletter to learn about new content!

Educators Newsletter Email * If you are human, leave this field blank. Sign Up

Get updated about new videos!

Newsletter Email * If you are human, leave this field blank. Sign Up

Infographic

This gave students an opportunity to watch a video to identify key factors in our judicial system, then even followed up with a brief research to demonstrate how this case, which is seemingly non-impactful on the contemporary student, connect to them in a meaningful way

This is a great product. I have used it over and over again. It is well laid out and suits the needs of my students. I really appreciate all the time put into making this product and thank you for sharing.

Appreciate this resource; adding it to my collection for use in AP US Government.

I thoroughly enjoyed this lesson plan and so do my students. It is always nice when I don't have to write my own lesson plan

Sign up to receive our monthly newsletter!

- Academy 4SC

- Educators 4SC

- Leaders 4SC

- Students 4SC

- Research 4SC

Accountability

Navigation menu

Personal tools.

- View source

- View history

- Encyclopedia Home

- Alphabetical List of Entries

- Topical List

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers originated as a series of articles in a New York newspaper in 1787–88. Published anonymously under the pen name of “Publius,” they were written primarily for instrumental political purposes: to promote ratification of the Constitution and defend it against its critics.

Initiated by Alexander Hamilton , the series came to eighty-five articles, the majority by Hamilton himself, twenty-six by James Madison , and five by John Jay. The Federalist was the title under which Hamilton collected the papers for publication as a book.

Despite their polemical origin, the papers are widely viewed as the best work of political philosophy produced in the United States, and as the best expositions of the Constitution to be found amidst all the ratification debates. They are frequently cited for discerning the meaning of the Constitution and the intentions of the founders, although Hamilton’s papers are not always reliable as an exposition of his views: in The Federalist , Hamilton took care to avoid coming out clearly with his views on either the inadequacies of the Constitution or the potentiality for using it dynamically. Instead, he expressed himself indirectly, arguing that the only real danger would arise from the potential weaknesses of the central government under the Constitution , not from its potentialities for greater strength as charged by its opponents. Despite this, The Federalist can be and frequently has been referred to for its exposition of Hamilton’s position on executive authority, judicial review, and other institutional aspects of the Constitution.

The Federalist Papers are also admired abroad—sometimes more than in the United States. Hamilton is held in high esteem abroad: while in America his realist style is received with suspicion of undemocratic intentions, abroad it is taken as a reassurance of solidity, and it is the Jeffersonian idealist style that is received with suspicion of hidden intentions. The Federalist Papers are studied by jurists and legal scholars and cited for writing other countries’ constitutions. In this capacity they have played a significant role in the spread of federal, democratic, and constitutional governments around the world.

- 1 MODERN FEDERATION AS EXPOUNDED BY THE FEDERALIST

- 2 AMBIGUITIES OF COORDINATE FEDERALISM IN THE FEDERALIST

- 3 USE AND ABUSE OF THE FEDERALIST

- 4.1 Ira Straus

MODERN FEDERATION AS EXPOUNDED BY THE FEDERALIST

The Federalist Papers defended a new form of federalism : what it called “federation” as differentiated from “confederation.” There were precursors for this usage; The Federalist Papers solidified it. All subsequent federalism has been influenced by the example of “federation” in the United States; indeed, the success of it in the United States has led to its being known as “modern federation” in contrast to “classical confederation.” In its basic structures and principles, it has served as the model for most subsequent federal unions, as well as for the reform of older confederacies such as Switzerland.

The main distinguishing characteristics of the model of modern federation, elucidated and defended by The Federalist Papers , are as follows:

1. The federal government’s most important figures, the legislative, are elected largely by the individual citizens, rather than being primarily selected by the governments of member states as in confederation.

2. Conversely, federal law applies directly to individuals, through federal courts and agencies, rather than to member states as in confederation.