- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Critical thinking arguments for beginners

Critical thinking is one of the most valuable sets of life skills you can ever have and it’s never too late to learn them. People who can think critically are better at problem solving of all kinds, whether at school or work, in ordinary daily life, and even in crises. You can practice critical thinking by working through typical arguments from premises to conclusions.

Thinking critically isn’t about following a single path to an inevitable conclusion. It’s about developing a set of powerful and versatile mental processing tools in your head and being able to apply these meaningfully to the world around you.

You need no special qualifications to become a strong critical thinker, and can’t pick it up simply from reading books about critical thinking . The only way to hone critical thinking skills is to practice critical thinking.

If you’re ready to learn more about critical thinking arguments for beginners then read on…

What is critical thinking?

Let’s first illustrate the answer to this question by taking a look at how we can think critically about potential misinformation online.

Your friend on a social media site has shared a photograph of election ballot slips apparently being tipped into a river by a postal truck driver, reportedly a supporter of a political party who will benefit from lower postal voter turnout.

Your friend is a supporter of another party and expresses outrage at the alleged law-breaking, election influencing, and reduced chances for her own party candidate. Many other friends pile in with sympathetic and equally outraged comments, or new allegations.

The temptation might be strong to accept the narrative caption which accompanies the picture, echo your friends’ emotional responses, and share the photo further. However, as a critical thinker, you should step back and ask some crucial questions first:

- Is the photo obviously manipulated? Sophisticated image alterations can now be made which won’t be spotted by the majority of non-experts. Could this be an image of a simple truck crash with ballot papers photoshopped in?

- Does your friend fact-check stories, pictures, memes etc.. before posting them online? If she has a history of posting stories which turned out to be false, it reduces her credibility in presenting the current story.

- I s there anything in the photograph which supports or undermines the claims made? If you can see that the van has a foreign registration plate, the ballot papers aren’t in English, or the date on the clock is actually several years ago, it is clear that the true story is somewhat different to the one being told.

Let’s say that your initial suspicions after asking yourself these questions are enough that you do a quick web search for the story.

Your search reveals that credible sources have already uncovered the photo as having been manipulated and spread by an online political group. It was originally a local news story about a crashed postal truck in another country five years earlier and has no relationship whatsoever to the current election in your country…

Your critical thinking helped you to avoid falling into group-think along with your friends and saved you from spreading more misinformation online. These real life type examples are are an excellent way to grasp the relevance and value of critical thinking arguments for beginners.

Now for a little of the theory. Critical thinking is a description that brings together a range of useful intellectual skills and their synergies. While there is no definitive list, there are some common key competences necessary for critical thinking :

- Conducting analysis. Being able to understand the issue in question; distinguish between relevant and irrelevant information; identify commonalities, differences and connections.

- Making inferences. Using inductive or deductive reasoning to draw out meanings; identifying assumptions; abstracting ideas; applying analogies and recognizing cause and effect relationships in order to develop theories or potential conclusions.

- Evaluating evidence. Making a judgement about whether a theory or statement is credible or correct; adjusting views and theories in the light of new data or perspectives; grasping the significance of events and information.

- Making robust decisions. Reaching sound conclusions by applying critical thinking skills to the available evidence.

To apply critical thinking in real life, you also need to possess the right attitude to problem solving, as well as the critical thinking skills themselves.

This means being automatically inclined to think critically in the face of a difficult question or problem. Being fair, open-minded, curious and free from ideology or group-think will all help to create a mindset in which critical thinking can thrive.

What are critical thinking arguments?

Let’s now look at some of the basic building blocks underpinning critical thinking arguments for beginners.

In critical thinking and logic, ‘argument’ has a particular meaning. It refers to a set of statements, consisting of one conclusion and one or more premises. The conclusion is the statement that the argument is intended to prove. The premises are the reasons offered for believing that the conclusion is true.

A critical thinking argument could use a deductive reasoning approach, an inductive reasoning approach, or both.

Deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning attempts to absolutely guarantee a conclusion’s truth through logic. If a deductive argument’s premises are true, it should be impossible for its conclusion to be false. For example:

- All humans are mortal. (Premise)

- Socrates is a human. (Premise)

- Therefore, Socrates is mortal. (Conclusion)

Inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning attempts to show that the conclusion is probably true, with each premise making the case for the conclusion stronger or weaker. For example:

- Three independent witnesses saw Max climb in through the window of the house. (Premise)

- Max’s fingerprints are on the window frame and several stolen items. (Premise)

- Max confessed to the burglary. (Premise)

- Therefore, Max committed the burglary. (Conclusion)

Do note that in either case, straight assertions, explanations or conditional sentences are not arguments.

How do I assess a critical thinking argument?

You can evaluate whether an argument is valid or invalid, sound or unsound, strong or weak .

If an argument is said to be ‘valid’, it means that it is impossible for the conclusion to be false if the premises are true. If an argument is ‘invalid’, it is possible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

An argument is ‘sound’ if it is both valid and contains only true premises. If either of these conditions isn’t met then the argument is ‘unsound’.

A deductively ‘strong’ argument is both valid and it is reasonable for the person in question to believe the premises are true. In a deductively weak argument , the person considering the premises may have good reason to doubt them.

When an argument is inductively strong, the truth of the premises makes the the truth of the conclusion probable. In contrast, in an inductively ‘weak’ argument, the truth of the premises do not make the truth of the conclusion probable.

Counterexamples

A ‘counterexample’ is a consistent story which shows that an argument can have true premises but a false conclusion, rendering it invalid.

NB A valid argument is not necessarily true, and a weak argument is not necessarily false.

All of these fundamentals can be applied both to simple practice arguments and then to more complex problems of the type you might encounter in real life.

For example:

- All unicorns are Swedish (Premise)

- My new pet is a unicorn (Premise)

- Therefore, my new pet is Swedish (Conclusion)

The premises here are both false – unicorns do not exist, and I therefore cannot own one as a pet. However, if they were true, then the conclusion would be true. What we have here is a valid argument, but not a sound one, nor a strong one.

How can I practice critical thinking arguments for beginners?

Now that you have the basic tools and concepts for putting together a critical thinking argument, you can look out for real life examples to practice with.

News stories

Look at the headlines covering stories in TV, online or paper news. Do you agree that the facts of the story are credible and constitute premises strong enough to justify the headline drawn from them?

Social media

Critically examine stories and claims shared by friends and contacts online. Ask yourself whether the evidence presented is credible and justifies the claims being made.

Corporate statements

Evaluate claims made by big corporations in public statements and annual reports alongside their actions and impacts. For example, if a major oil company claims that it is working to combat climate change, how strong, valid and sound are their arguments?

Conclusion…

Whatever your starting point, we hope this article has set you on the road to becoming a critical thinker, and that these developing skills might open new doors at school, at work or in other areas of life. The world needs more critical thinking at all levels and your contribution might one day be valuable.

You may also like

10 modern day thought leaders on critical thinking

Critical thinking is a vital skill that enables individuals to analyze, evaluate, and interpret information effectively. In today’s dynamic environment, it has […]

Divergent vs Convergent Thinking – What are They and How are They Different?

They say that necessity is the mother of invention but without a dash of creativity and clear thinking, innovation would stall out […]

5 Activities that Will Teach Children about Critical Thinking

Teaching your children to dig deeper and solve problems with a higher level of thinking can be tough. But as a parent, […]

Divergent Thinking Examples

You may have heard of divergent and convergent thinking. These are two different ways of coming up with solutions to problems. While […]

Pursuing Truth: A Guide to Critical Thinking

Chapter 2 arguments.

The fundamental tool of the critical thinker is the argument. For a good example of what we are not talking about, consider a bit from a famous sketch by Monty Python’s Flying Circus : 3

2.1 Identifying Arguments

People often use “argument” to refer to a dispute or quarrel between people. In critical thinking, an argument is defined as

A set of statements, one of which is the conclusion and the others are the premises.

There are three important things to remember here:

- Arguments contain statements.

- They have a conclusion.

- They have at least one premise

Arguments contain statements, or declarative sentences. Statements, unlike questions or commands, have a truth value. Statements assert that the world is a particular way; questions do not. For example, if someone asked you what you did after dinner yesterday evening, you wouldn’t accuse them of lying. When the world is the way that the statement says that it is, we say that the statement is true. If the statement is not true, it is false.

One of the statements in the argument is called the conclusion. The conclusion is the statement that is intended to be proved. Consider the following argument:

Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I. Susan did well in Calculus I. So, Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Here the conclusion is that Susan should do well in Calculus II. The other two sentences are premises. Premises are the reasons offered for believing that the conclusion is true.

2.1.1 Standard Form

Now, to make the argument easier to evaluate, we will put it into what is called “standard form.” To put an argument in standard form, write each premise on a separate, numbered line. Draw a line underneath the last premise, the write the conclusion underneath the line.

- Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I.

- Susan did well in Calculus I.

- Susan should do well in Calculus II.

Now that we have the argument in standard form, we can talk about premise 1, premise 2, and all clearly be referring to the same thing.

2.1.2 Indicator Words

Unfortunately, when people present arguments, they rarely put them in standard form. So, we have to decide which statement is intended to be the conclusion, and which are the premises. Don’t make the mistake of assuming that the conclusion comes at the end. The conclusion is often at the beginning of the passage, but could even be in the middle. A better way to identify premises and conclusions is to look for indicator words. Indicator words are words that signal that statement following the indicator is a premise or conclusion. The example above used a common indicator word for a conclusion, ‘so.’ The other common conclusion indicator, as you can probably guess, is ‘therefore.’ This table lists the indicator words you might encounter.

Each argument will likely use only one indicator word or phrase. When the conlusion is at the end, it will generally be preceded by a conclusion indicator. Everything else, then, is a premise. When the conclusion comes at the beginning, the next sentence will usually be introduced by a premise indicator. All of the following sentences will also be premises.

For example, here’s our previous argument rewritten to use a premise indicator:

Susan should do well in Calculus II, because Calculus II will be no harder than Calculus I, and Susan did well in Calculus I.

Sometimes, an argument will contain no indicator words at all. In that case, the best thing to do is to determine which of the premises would logically follow from the others. If there is one, then it is the conclusion. Here is an example:

Spot is a mammal. All dogs are mammals, and Spot is a dog.

The first sentence logically follows from the others, so it is the conclusion. When using this method, we are forced to assume that the person giving the argument is rational and logical, which might not be true.

2.1.3 Non-Arguments

One thing that complicates our task of identifying arguments is that there are many passages that, although they look like arguments, are not arguments. The most common types are:

- Explanations

- Mere asssertions

- Conditional statements

- Loosely connected statements

Explanations can be tricky, because they often use one of our indicator words. Consider this passage:

Abraham Lincoln died because he was shot.

If this were an argument, then the conclusion would be that Abraham Lincoln died, since the other statement is introduced by a premise indicator. If this is an argument, though, it’s a strange one. Do you really think that someone would be trying to prove that Abraham Lincoln died? Surely everyone knows that he is dead. On the other hand, there might be people who don’t know how he died. This passage does not attempt to prove that something is true, but instead attempts to explain why it is true. To determine if a passage is an explanation or an argument, first find the statement that looks like the conclusion. Next, ask yourself if everyone likely already believes that statement to be true. If the answer to that question is yes, then the passage is an explanation.

Mere assertions are obviously not arguments. If a professor tells you simply that you will not get an A in her course this semester, she has not given you an argument. This is because she hasn’t given you any reasons to believe that the statement is true. If there are no premises, then there is no argument.

Conditional statements are sentences that have the form “If…, then….” A conditional statement asserts that if something is true, then something else would be true also. For example, imagine you are told, “If you have the winning lottery ticket, then you will win ten million dollars.” What is being claimed to be true, that you have the winning lottery ticket, or that you will win ten million dollars? Neither. The only thing claimed is the entire conditional. Conditionals can be premises, and they can be conclusions. They can be parts of arguments, but that cannot, on their own, be arguments themselves.

Finally, consider this passage:

I woke up this morning, then took a shower and got dressed. After breakfast, I worked on chapter 2 of the critical thinking text. I then took a break and drank some more coffee….

This might be a description of my day, but it’s not an argument. There’s nothing in the passage that plays the role of a premise or a conclusion. The passage doesn’t attempt to prove anything. Remember that arguments need a conclusion, there must be something that is the statement to be proved. Lacking that, it simply isn’t an argument, no matter how much it looks like one.

2.2 Evaluating Arguments

The first step in evaluating an argument is to determine what kind of argument it is. We initially categorize arguments as either deductive or inductive, defined roughly in terms of their goals. In deductive arguments, the truth of the premises is intended to absolutely establish the truth of the conclusion. For inductive arguments, the truth of the premises is only intended to establish the probable truth of the conclusion. We’ll focus on deductive arguments first, then examine inductive arguments in later chapters.

Once we have established that an argument is deductive, we then ask if it is valid. To say that an argument is valid is to claim that there is a very special logical relationship between the premises and the conclusion, such that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Another way to state this is

An argument is valid if and only if it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

An argument is invalid if and only if it is not valid.

Note that claiming that an argument is valid is not the same as claiming that it has a true conclusion, nor is it to claim that the argument has true premises. Claiming that an argument is valid is claiming nothing more that the premises, if they were true , would be enough to make the conclusion true. For example, is the following argument valid or not?

- If pigs fly, then an increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

- An increase in the minimum wage will be approved next term.

The argument is indeed valid. If the two premises were true, then the conclusion would have to be true also. What about this argument?

- All dogs are mammals

- Spot is a mammal.

- Spot is a dog.

In this case, both of the premises are true and the conclusion is true. The question to ask, though, is whether the premises absolutely guarantee that the conclusion is true. The answer here is no. The two premises could be true and the conclusion false if Spot were a cat, whale, etc.

Neither of these arguments are good. The second fails because it is invalid. The two premises don’t prove that the conclusion is true. The first argument is valid, however. So, the premises would prove that the conclusion is true, if those premises were themselves true. Unfortunately, (or fortunately, I guess, considering what would be dropping from the sky) pigs don’t fly.

These examples give us two important ways that deductive arguments can fail. The can fail because they are invalid, or because they have at least one false premise. Of course, these are not mutually exclusive, an argument can be both invalid and have a false premise.

If the argument is valid, and has all true premises, then it is a sound argument. Sound arguments always have true conclusions.

A deductively valid argument with all true premises.

Inductive arguments are never valid, since the premises only establish the probable truth of the conclusion. So, we evaluate inductive arguments according to their strength. A strong inductive argument is one in which the truth of the premises really do make the conclusion probably true. An argument is weak if the truth of the premises fail to establish the probable truth of the conclusion.

There is a significant difference between valid/invalid and strong/weak. If an argument is not valid, then it is invalid. The two categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive. There can be no such thing as an argument being more valid than another valid argument. Validity is all or nothing. Inductive strength, however, is on a continuum. A strong inductive argument can be made stronger with the addition of another premise. More evidence can raise the probability of the conclusion. A valid argument cannot be made more valid with an additional premise. Why not? If the argument is valid, then the premises were enough to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion. Adding another premise won’t give any more guarantee of truth than was already there. If it could, then the guarantee wasn’t absolute before, and the original argument wasn’t valid in the first place.

2.3 Counterexamples

One way to prove an argument to be invalid is to use a counterexample. A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises are true and the conclusion false. Consider the argument above:

By pointing out that Spot could have been a cat, I have told a story in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is false.

Here’s another one:

- If it is raining, then the sidewalks are wet.

- The sidewalks are wet.

- It is raining.

The sprinklers might have been on. If so, then the sidewalks would be wet, even if it weren’t raining.

Counterexamples can be very useful for demonstrating invalidity. Keep in mind, though, that validity can never be proved with the counterexample method. If the argument is valid, then it will be impossible to give a counterexample to it. If you can’t come up with a counterexample, however, that does not prove the argument to be valid. It may only mean that you’re not creative enough.

- An argument is a set of statements; one is the conclusion, the rest are premises.

- The conclusion is the statement that the argument is trying to prove.

- The premises are the reasons offered for believing the conclusion to be true.

- Explanations, conditional sentences, and mere assertions are not arguments.

- Deductive reasoning attempts to absolutely guarantee the truth of the conclusion.

- Inductive reasoning attempts to show that the conclusion is probably true.

- In a valid argument, it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

- In an invalid argument, it is possible for the premises to be true and the conclusion false.

- A sound argument is valid and has all true premises.

- An inductively strong argument is one in which the truth of the premises makes the the truth of the conclusion probable.

- An inductively weak argument is one in which the truth of the premises do not make the conclusion probably true.

- A counterexample is a consistent story in which the premises of an argument are true and the conclusion is false. Counterexamples can be used to prove that arguments are deductively invalid.

( Cleese and Chapman 1980 ) . ↩︎

2 Logic and the Study of Arguments

If we want to study how we ought to reason (normative) we should start by looking at the primary way that we do reason (descriptive): through the use of arguments. In order to develop a theory of good reasoning, we will start with an account of what an argument is and then proceed to talk about what constitutes a “good” argument.

I. Arguments

- Arguments are a set of statements (premises and conclusion).

- The premises provide evidence, reasons, and grounds for the conclusion.

- The conclusion is what is being argued for.

- An argument attempts to draw some logical connection between the premises and the conclusion.

- And in doing so, the argument expresses an inference: a process of reasoning from the truth of the premises to the truth of the conclusion.

Example : The world will end on August 6, 2045. I know this because my dad told me so and my dad is smart.

In this instance, the conclusion is the first sentence (“The world will end…”); the premises (however dubious) are revealed in the second sentence (“I know this because…”).

II. Statements

Conclusions and premises are articulated in the form of statements . Statements are sentences that can be determined to possess or lack truth. Some examples of true-or-false statements can be found below. (Notice that while some statements are categorically true or false, others may or may not be true depending on when they are made or who is making them.)

Examples of sentences that are statements:

- It is below 40°F outside.

- Oklahoma is north of Texas.

- The Denver Broncos will make it to the Super Bowl.

- Russell Westbrook is the best point guard in the league.

- I like broccoli.

- I shouldn’t eat French fries.

- Time travel is possible.

- If time travel is possible, then you can be your own father or mother.

However, there are many sentences that cannot so easily be determined to be true or false. For this reason, these sentences identified below are not considered statements.

- Questions: “What time is it?”

- Commands: “Do your homework.”

- Requests: “Please clean the kitchen.”

- Proposals: “Let’s go to the museum tomorrow.”

Question: Why are arguments only made up of statements?

First, we only believe statements . It doesn’t make sense to talk about believing questions, commands, requests or proposals. Contrast sentences on the left that are not statements with sentences on the right that are statements:

It would be non-sensical to say that we believe the non-statements (e.g. “I believe what time is it?”). But it makes perfect sense to say that we believe the statements (e.g. “I believe the time is 11 a.m.”). If conclusions are the statements being argued for, then they are also ideas we are being persuaded to believe. Therefore, only statements can be conclusions.

Second, only statements can provide reasons to believe.

- Q: Why should I believe that it is 11:00 a.m.? A: Because the clock says it is 11a.m.

- Q: Why should I believe that we are going to the museum tomorrow? A: Because today we are making plans to go.

Sentences that cannot be true or false cannot provide reasons to believe. So, if premises are meant to provide reasons to believe, then only statements can be premises.

III. Representing Arguments

As we concern ourselves with arguments, we will want to represent our arguments in some way, indicating which statements are the premises and which statement is the conclusion. We shall represent arguments in two ways. For both ways, we will number the premises.

In order to identify the conclusion, we will either label the conclusion with a (c) or (conclusion). Or we will mark the conclusion with the ∴ symbol

Example Argument:

There will be a war in the next year. I know this because there has been a massive buildup in weapons. And every time there is a massive buildup in weapons, there is a war. My guru said the world will end on August 6, 2045.

- There has been a massive buildup in weapons.

- Every time there has been a massive buildup in weapons, there is a war.

(c) There will be a war in the next year.

∴ There will be a war in the next year.

Of course, arguments do not come labeled as such. And so we must be able to look at a passage and identify whether the passage contains an argument and if it does, we should also be identify which statements are the premises and which statement is the conclusion. This is harder than you might think!

There is no argument here. There is no statement being argued for. There are no statements being used as reasons to believe. This is simply a report of information.

The following are also not arguments:

Advice: Be good to your friends; your friends will be good to you.

Warnings: No lifeguard on duty. Be careful.

Associated claims: Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to the dark side.

When you have an argument, the passage will express some process of reasoning. There will be statements presented that serve to help the speaker building a case for the conclusion.

IV. How to L ook for A rguments [1]

How do we identify arguments in real life? There are no easy, mechanical rules, and we usually have to rely on the context in order to determine which are the premises and the conclusions. But sometimes the job can be made easier by the presence of certain premise or conclusion indicators. For example, if a person makes a statement, and then adds “this is because …,” then it is quite likely that the first statement is presented as a conclusion, supported by the statements that come afterward. Other words in English that might be used to indicate the premises to follow include:

- firstly, secondly, …

- for, as, after all

- assuming that, in view of the fact that

- follows from, as shown / indicated by

- may be inferred / deduced / derived from

Of course whether such words are used to indicate premises or not depends on the context. For example, “since” has a very different function in a statement like “I have been here since noon,” unlike “X is an even number since X is divisible by 4.” In the first instance (“since noon”) “since” means “from.” In the second instance, “since” means “because.”

Conclusions, on the other hand, are often preceded by words like:

- therefore, so, it follows that

- hence, consequently

- suggests / proves / demonstrates that

- entails, implies

Here are some examples of passages that do not contain arguments.

1. When people sweat a lot they tend to drink more water. [Just a single statement, not enough to make an argument.]

2. Once upon a time there was a prince and a princess. They lived happily together and one day they decided to have a baby. But the baby grew up to be a nasty and cruel person and they regret it very much. [A chronological description of facts composed of statements but no premise or conclusion.]

3. Can you come to the meeting tomorrow? [A question that does not contain an argument.]

Do these passages contain arguments? If so, what are their conclusions?

- Cutting the interest rate will have no effect on the stock market this time around, as people have been expecting a rate cut all along. This factor has already been reflected in the market.

- So it is raining heavily and this building might collapse. But I don’t really care.

- Virgin would then dominate the rail system. Is that something the government should worry about? Not necessarily. The industry is regulated, and one powerful company might at least offer a more coherent schedule of services than the present arrangement has produced. The reason the industry was broken up into more than 100 companies at privatization was not operational, but political: the Conservative government thought it would thus be harder to renationalize (The Economist 12/16/2000).

- Bill will pay the ransom. After all, he loves his wife and children and would do everything to save them.

- All of Russia’s problems of human rights and democracy come back to three things: the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. None works as well as it should. Parliament passes laws in a hurry, and has neither the ability nor the will to call high officials to account. State officials abuse human rights (either on their own, or on orders from on high) and work with remarkable slowness and disorganization. The courts almost completely fail in their role as the ultimate safeguard of freedom and order (The Economist 11/25/2000).

- Most mornings, Park Chang Woo arrives at a train station in central Seoul, South Korea’s capital. But he is not commuter. He is unemployed and goes there to kill time. Around him, dozens of jobless people pass their days drinking soju, a local version of vodka. For the moment, middle-aged Mr. Park would rather read a newspaper. He used to be a bricklayer for a small construction company in Pusan, a southern port city. But three years ago the country’s financial crisis cost him that job, so he came to Seoul, leaving his wife and two children behind. Still looking for work, he has little hope of going home any time soon (The Economist 11/25/2000).

- For a long time, astronomers suspected that Europa, one of Jupiter’s many moons, might harbour a watery ocean beneath its ice-covered surface. They were right. Now the technique used earlier this year to demonstrate the existence of the Europan ocean has been employed to detect an ocean on another Jovian satellite, Ganymede, according to work announced at the recent American Geo-physical Union meeting in San Francisco (The Economist 12/16/2000).

- There are no hard numbers, but the evidence from Asia’s expatriate community is unequivocal. Three years after its handover from Britain to China, Hong Kong is unlearning English. The city’s gweilos (Cantonese for “ghost men”) must go to ever greater lengths to catch the oldest taxi driver available to maximize their chances of comprehension. Hotel managers are complaining that they can no longer find enough English-speakers to act as receptionists. Departing tourists, polled at the airport, voice growing frustration at not being understood (The Economist 1/20/2001).

V. Evaluating Arguments

Q: What does it mean for an argument to be good? What are the different ways in which arguments can be good? Good arguments:

- Are persuasive.

- Have premises that provide good evidence for the conclusion.

- Contain premises that are true.

- Reach a true conclusion.

- Provide the audience good reasons for accepting the conclusion.

The focus of logic is primarily about one type of goodness: The logical relationship between premises and conclusion.

An argument is good in this sense if the premises provide good evidence for the conclusion. But what does it mean for premises to provide good evidence? We need some new concepts to capture this idea of premises providing good logical support. In order to do so, we will first need to distinguish between two types of argument.

VI. Two Types of Arguments

The two main types of arguments are called deductive and inductive arguments. We differentiate them in terms of the type of support that the premises are meant to provide for the conclusion.

Deductive Arguments are arguments in which the premises are meant to provide conclusive logical support for the conclusion.

1. All humans are mortal

2. Socrates is a human.

∴ Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

1. No student in this class will fail.

2. Mary is a student in this class.

∴ Therefore, Mary will not fail.

1. A intersects lines B and C.

2. Lines A and B form a 90-degree angle

3. Lines A and C form a 90-degree angle.

∴ B and C are parallel lines.

Inductive arguments are, by their very nature, risky arguments.

Arguments in which premises provide probable support for the conclusion.

Statistical Examples:

1. Ten percent of all customers in this restaurant order soda.

2. John is a customer.

∴ John will not order Soda..

1. Some students work on campus.

2. Bill is a student.

∴ Bill works on campus.

1. Vegas has the Carolina Panthers as a six-point favorite for the super bowl.

∴ Carolina will win the Super Bowl.

VII. Good Deductive Arguments

The First Type of Goodness: Premises play their function – they provide conclusive logical support.

Deductive and inductive arguments have different aims. Deductive argument attempt to provide conclusive support or reasons; inductive argument attempt to provide probable reasons or support. So we must evaluate these two types of arguments.

Deductive arguments attempt to be valid.

To put validity in another way: if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true.

It is very important to note that validity has nothing to do with whether or not the premises are, in fact, true and whether or not the conclusion is in fact true; it merely has to do with a certain conditional claim. If the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true.

Q: What does this mean?

- The validity of an argument does not depend upon the actual world. Rather, it depends upon the world described by the premises.

- First, consider the world described by the premises. In this world, is it logically possible for the conclusion to be false? That is, can you even imagine a world in which the conclusion is false?

Reflection Questions:

- If you cannot, then why not?

- If you can, then provide an example of a valid argument.

You should convince yourself that validity is not just about the actual truth or falsity of the premises and conclusion. Rather, validity only has to do with a certain logical relationship between the truth of the premise and the truth of the conclusion. So the only possible combination that is ruled out by a valid argument is a set of true premises and false conclusion.

Let’s go back to example #1. Here are the premises:

1. All humans are mortal.

If both of these premises are true, then every human that we find must be a mortal. And this means, that it must be the case that if Socrates is a human, that Socrates is mortal.

Reflection Questions about Invalid Arguments:

- Can you have an invalid argument with a true premise?

- Can you have an invalid argument with true premises and a true conclusion?

The s econd type of goodness for deductive arguments: The premises provide us the right reasons to accept the conclusion.

Soundness V ersus V alidity:

Our original argument is a sound one:

∴ Socrates is mortal.

Question: Can a sound argument have a false conclusion?

VIII. From Deductive Arguments to Inductive Arguments

Question: What happens if we mix around the premises and conclusion?

2. Socrates is mortal.

∴ Socrates is a human.

1. Socrates is mortal

∴ All humans are mortal.

Are these valid deductive arguments?

NO, but they are common inductive arguments.

Other examples :

Suppose that there are two opaque glass jars with different color marbles in them.

1. All the marbles in jar #1 are blue.

2. This marble is blue.

∴ This marble came from jar #1.

1. This marble came from jar #2.

2. This marble is red.

∴ All the marbles in jar #2 are red.

While this is a very risky argument, what if we drew 100 marbles from jar #2 and found that they were all red? Would this affect the second argument’s validity?

IX. Inductive Arguments:

The aim of an inductive argument is different from the aim of deductive argument because the type of reasons we are trying to provide are different. Therefore, the function of the premises is different in deductive and inductive arguments. And again, we can split up goodness into two types when considering inductive arguments:

- The premises provide the right logical support.

- The premises provide the right type of reason.

Logical S upport:

Remember that for inductive arguments, the premises are intended to provide probable support for the conclusion. Thus, we shall begin by discussing a fairly rough, coarse-grained way of talking about probable support by introducing the notions of strong and weak inductive arguments.

A strong inductive argument:

- The vast majority of Europeans speak at least two languages.

- Sam is a European.

∴ Sam speaks two languages.

Weak inductive argument:

- This quarter is a fair coin.

∴ Therefore, the next coin flip will land heads.

- At least one dog in this town has rabies.

- Fido is a dog that lives in this town.

∴ Fido has rabies.

The R ight T ype of R easons. As we noted above, the right type of reasons are true statements. So what happens when we get an inductive argument that is good in the first sense (right type of logical support) and good in the second sense (the right type of reasons)? Corresponding to the notion of soundness for deductive arguments, we call inductive arguments that are good in both senses cogent arguments.

- With which of the following types of premises and conclusions can you have a strong inductive argument?

- With which of the following types of premises and conclusions can you have a cogent inductive argument?

X. Steps for Evaluating Arguments:

- Read a passage and assess whether or not it contains an argument.

- If it does contain an argument, then identify the conclusion and premises.

- If yes, then assess it for soundness.

- If not, then treat it as an inductive argument (step 3).

- If the inductive argument is strong, then is it cogent?

XI. Evaluating Real – World Arguments

An important part of evaluating arguments is not to represent the arguments of others in a deliberately weak way.

For example, suppose that I state the following:

All humans are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.

Is this valid? Not as it stands. But clearly, I believe that Socrates is a human being. Or I thought that was assumed in the conversation. That premise was clearly an implicit one.

So one of the things we can do in the evaluation of argument is to take an argument as it is stated, and represent it in a way such that it is a valid deductive argument or a strong inductive one. In doing so, we are making explicit what one would have to assume to provide a good argument (in the sense that the premises provide good – conclusive or probable – reason to accept the conclusion).

The teacher’s policy on extra credit was unfair because Sally was the only person to have a chance at receiving extra credit.

- Sally was the only person to have a chance at receiving extra credit.

- The teacher’s policy on extra credit is fair only if everyone gets a chance to receive extra credit.

Therefore, the teacher’s policy on extra credit was unfair.

Valid argument

Sally didn’t train very hard so she didn’t win the race.

- Sally didn’t train very hard.

- If you don’t train hard, you won’t win the race.

Therefore, Sally didn’t win the race.

Strong (not valid):

- If you won the race, you trained hard.

- Those who don’t train hard are likely not to win.

Therefore, Sally didn’t win.

Ordinary workers receive worker’s compensation benefits if they suffer an on-the-job injury. However, universities have no obligations to pay similar compensation to student athletes if they are hurt while playing sports. So, universities are not doing what they should.

- Ordinary workers receive worker’s compensation benefits if they suffer an on-the-job injury that prevents them working.

- Student athletes are just like ordinary workers except that their job is to play sports.

- So if student athletes are injured while playing sports, they should also be provided worker’s compensation benefits.

- Universities have no obligations to provide injured student athletes compensation.

Therefore, universities are not doing what they should.

Deductively valid argument

If Obama couldn’t implement a single-payer healthcare system in his first term as president, then the next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

- Obama couldn’t implement a single-payer healthcare system.

- In Obama’s first term as president, both the House and Senate were under Democratic control.

- The next president will either be dealing with the Republican-controlled house and senate or at best, a split legislature.

- Obama’s first term as president will be much easier than the next president’s term in terms of passing legislation.

Therefore, the next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

Strong inductive argument

Sam is weaker than John. Sam is slower than John. So Sam’s time on the obstacle will be slower than John’s.

- Sam is weaker than John.

- Sam is slower than John.

- A person’s strength and speed inversely correlate with their time on the obstacle course.

Therefore, Sam’s time will be slower than John’s.

XII. Diagramming Arguments

All the arguments we’ve dealt with – except for the last two – have been fairly simple in that the premises always provided direct support for the conclusion. But in many arguments, such as the last one, there are often arguments within arguments.

Obama example :

- The next president will either be dealing with the Republican controlled house and senate or at best, a split legislature.

∴ The next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

It’s clear that premises #2 and #3 are used in support of #4. And #1 in combination with #4 provides support for the conclusion.

When we diagram arguments, the aim is to represent the logical relationships between premises and conclusion. More specifically, we want to identify what each premise supports and how.

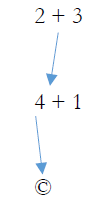

This represents that 2+3 together provide support for 4

This represents that 4+1 together provide support for 5

When we say that 2+3 together or 4+1 together support some statement, we mean that the logical support of these statements are dependent upon each other. Without the other, these statements would not provide evidence for the conclusion. In order to identify when statements are dependent upon one another, we simply underline the set that are logically dependent upon one another for their evidential support. Every argument has a single conclusion, which the premises support; therefore, every argument diagram should point to the conclusion (c).

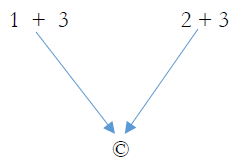

Sam Example:

- Sam is less flexible than John.

- A person’s strength and flexibility inversely correlate with their time on the obstacle course.

∴ Therefore, Sam’s time will be slower than John’s.

In some cases, different sets of premises provide evidence for the conclusion independently of one another. In the argument above, there are two logically independent arguments for the conclusion that Sam’s time will be slower than John’s. That Sam is weaker than John and that being weaker correlates with a slower time provide evidence for the conclusion that Sam will be slower than John. Completely independent of this argument is the fact that Sam is less flexible and that being less flexible corresponds with a slower time. The diagram above represent these logical relations by showing that #1 and #3 dependently provide support for #4. Independent of that argument, #2 and #3 also dependently provide support for #4. Therefore, there are two logically independent sets of premises that provide support for the conclusion.

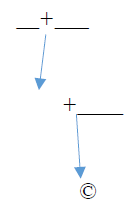

Try diagramming the following argument for yourself. The structure of the argument has been provided below:

- All humans are mortal

- Socrates is human

- So Socrates is mortal.

- If you feed a mortal person poison, he will die.

∴ Therefore, Socrates has been fed poison, so he will die.

- This section is taken from http://philosophy.hku.hk/think/ and is in use under creative commons license. Some modifications have been made to the original content. ↵

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Brian Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Structure and Function of Argument: Introduction to Critical Thinking

Explore the underlying structures of everyday arguments and develop the tools to communicate effectively..

You will build a toolkit to engage in more constructive conversations and to actively listen to better understand others’ points of view.

What You'll Learn

Life is full of arguments—you encounter them everyday in your social and professional circles. From casually discussing what to have for dinner tonight with your family to passionately debating the best candidate to vote for in the upcoming election, arguments are a method to better educate ourselves and understand others.

All arguments share an underlying mapping structure that backs a main claim with supporting reasons, sometimes including counterpoints to anticipated objections. In order to present an argument that will clearly communicate your perspective, you must first understand the basic structure of any argument and develop your logic and critical thinking skills.

In Structure and Function of Argument: Introduction to Critical Thinking, you will engage in dynamic practice exercises to develop the ability to recognize, analyze, and construct arguments you encounter on a daily basis. You will consider the structure of an argument, focusing on the underlying organization of claims and reasoning. You will determine if the reasons support the author or speaker’s main claim, build well-constructed responses, and grow your overall English language skills. You will also test your listening skills by recognizing how things like logical fallacies, conflicting points of view, and controversial subjects can impact effective communication.

Using a tool called “argument mapping,” you will visually diagram the structure of an argument to identify how reasons connect and function in an argument. You will then apply your learnings and test your own arguments using this tool – allowing you to gauge the overall quality of your arguments and take steps to make them stronger.

By the end of the course, you will have built a toolkit to engage in more constructive conversations and to actively listen to better understand others’ points of view.

The course will be delivered via edX and connect learners around the world. By the end of the course, participants will be able to:

- Explore the shape and structures of arguments you encounter daily, helping improve your overall communication and English language skills.

- Learn how to visually map an argument, analyzing, evaluating, and optimizing the strength of your argument along the way.

- Become a better listener by seeking to understand others’ perspectives and engaging in respectful discussion and disagreement.

- Experiment with philosophical thought experiments to build your argumentation skills.

- Build the tools to improve your logical reasoning and emotional intelligence by understanding how conflict and tension can impact communication.

- Improve your ability to think critically, seek to understand underlying assumptions, and identify biases – allowing you to create more compassionate, compelling, and convincing arguments.

- Learn how to regulate your emotional response to differing points of view, expressing genuine curiosity and inquisitiveness as a means to learn from the other party.

Your Instructor

Edward J. Hall is the Norman E. Vuilleumier Professor of Philosophy at Harvard University and works on a range of topics in metaphysics and epistemology that overlap with philosophy of science. He believes that philosophical discourse always goes better if the parties involved resolutely avoid any “burden-shifting” maneuvers, and that teaching always goes better if you bring cookies.

Aidan Kestigian, Ph.D. is an Associate of the Department of Philosophy at Harvard University and the Vice President for ThinkerAnalytix (TA), an education non-profit organization. TA programs are designed to help move learning and working communities from discord to discourse by building reasoning and communication skills. Aidan received her Ph.D. in Logic, Computation, and Methodology from Carnegie Mellon University in 2018, and taught logic and ethics to college students for a decade before and during her time at TA.

Nate Otey is the Lead Curriculum Consultant for ThinkerAnalytix and received his undergraduate degree in Philosophy and Mathematics from Harvard College, where he fell in love with teaching. He then served as a Fellow in the Harvard Department of Philosophy, where he led the development of ThinkerAnalytix curriculum and partnerships. He currently teaches at Boston Trinity Academy.

Ways to take this course

When you enroll in this course, you will have the option of pursuing a Verified Certificate or Auditing the Course.

A Verified Certificate costs $209 and provides unlimited access to full course materials, activities, tests, and forums. At the end of the course, learners who earn a passing grade can receive a certificate.

Alternatively, learners can Audit the course for free and have access to select course material, activities, tests, and forums. Please note that this track does not offer a certificate for learners who earn a passing grade.

Related Courses

Rhetoric: the art of persuasive writing and public speaking.

This course is an introduction to the theory and practice of rhetoric, the art of persuasive writing and speech. In it, learners will learn to construct and defend compelling arguments, an essential skill in many settings.

The Path to Happiness: What Chinese Philosophy Teaches us about the Good Life

Join Harvard professor Michael Puett to explore ancient Chinese philosophy to challenge assumptions of what it means to be happy and live a meaningful life.

Taught by lauded Harvard professor Michael Sandel, Justice explores critical analysis of classical and contemporary theories of justice, including discussion of present-day applications.

Wrestling with Philosophy

Official Website for Amitabha Palmer

Critical Thinking: Defining an Argument, Premises, and Conclusions

Defining an Argument Argument: vas is das? For most of us when we hear the word ‘argument’ we think of something we’d rather avoid. As it is commonly understood, an argument involves some sort of unpleasant confrontation (well, maybe not always unpleasant–it can feel pretty good when you win!). While this is one notion of ‘argument,’ it’s (generally) not what the term refers to in philosophy. In philosophy what we mean by argument is “ a set of reasons offered in support of a claim.” An argument, in this narrower sense, also generally implies some sort of structure . For now we’ll ignore the more particular structural aspects and focus on the two primary elements that make up an argument: premises and conclusions. Lets talk about conclusions first because their definition is pretty simple. A conclusion is the final assertion that is supported with evidence and reasons. What’s important is the relationship between premises and conclusions. The premises are independent reasons and evidence that support the conclusion. In an argument, the conclusion should follow from the premises. Lets consider a simple example: Reason (1): Everyone thought Miley Cyrus’ performance was a travesty. Reason (2): Some people thought her performance was offensive. Conclusion: Therefore, some people thought her performance was both a travesty and offensive. Notice that so long as we accept reason 1 and reason 2 as true, then we must also accept the conclusion. This is what we mean by “the conclusion ‘follows’ from the premises.” Lets examine premises a little more closely. A premise is any reason or evidence that supports the conclusion of the argument. In the context of arguments we can use ‘reasons’, ‘evidence’, and ‘premises’ interchangeably. For example, if my conclusion is that dogs are better pets than cats, I might offer the following reasons: (P1) dogs are generally more affectionate than cats and (P2) dogs are more responsive to their owners’ commands than cats. From my two premises, I infer my conclusion that (C) dogs are better pets than cats.

Lets return to the definition of an argument. Notice that in the definition, I’ve said that arguments are a set of reasons. While this isn’t always true, generally, a good argument will generally have more than one premise. Heuristics for Identifying Premises and Conclusions Now that we know what each concept is, lets look at how to identify each one as we might encounter them “in nature” (e.g., in an article, in a conversation, in a meme, in a homework exercise, etc…). First I’ll explain each heuristic, then I’ll apply them to some examples. Identifying conclusions: The easiest way to go about decomposing arguments is to first try to find the conclusion. This is a good strategy because there is usually only one conclusion so, if we can identify it, it means the rest of the passage are premises. For this reason, most of the heuristics focus on finding the conclusion. Heuristic 1: Look for the most controversial statement in the argument. The conclusion will generally be the most controversial statement in the argument. If you think about it, this makes sense. Typically arguments proceed by moving from assertions (i.e., premises) the audience agrees with then showing how these assertions imply something that the audience might not have previously agreed with. Heuristic 2: The conclusion is usually a statement that takes a position on an issue . By implication, the premises will be reasons that support the position on the issue (i.e., the conclusion). A good way to apply this heuristic is to ask “what is the arguer trying to get me to believe?”. The answer to this question is generally going to be the conclusion. Heuristic 3: The conclusion is usually ( but not always ) the first or last statement of the argument. Heuristic 4: The “because” test. Use this method you’re having trouble figuring which of 2 statements is the conclusion. The “because” test helps you figure out which statement is supporting which. Recall that the premise(s) always supports the conclusion. This method is best explained by using an example. Suppose you encounter an argument that goes something like this: It’s a good idea to eat lots of amazonian jungle fruit. It tastes delicious. Also, lots of facebook posts say that it cures cancer Suppose you’re having trouble deciding what the conclusion it. You’ve eliminated “it tastes delicious” as a candidate but you still have to choose between “it’s a good idea to eat lots of amazonian jungle fruit” and “lots of facebook posts say that it cures cancer”. To use the because test, read one statement after the other but insert the word “because” between the two and see what makes more sense. Lets try the two possibilities: A: It’s a good idea to eat lots of amazonian jungle fruit because lots of facebook posts say that it cures cancer. B: Lots of facebook posts say that amazonian jungle fruit cures cancer because it’s a good idea to eat lots of it. Which makes more sense? Which is providing support for which? The answer is A. Lots of facebook posts saying something is a reason (i.e. premise) to believe that it’s a good idea to eat amazonian jungle fruit–despite the fact that it’s not a very good reason… Identifying the Premises Heuristic 1: Identifying the premises once you’ve identified the conclusion is cake. Whatever isn’t contained in the conclusion is either a premise or “filler” (i.e., not relevant to the argument). We will explore the distinguishing between filler and relevant premises a bit later, so don’t worry about that distinction for now. Example 1 Gun availability should be regulated. Put simply, if your fellow citizens have easy access to guns, they’re more likely to kill you than if they don’t have access. Interestingly, this turned out to be true not just for the twenty-six developed countries analyzed, but on a State-to-State level too. http://listverse.com/2013/04/21/10-arguments-for-gun-control/

Ok, lets try heuristic #1. What’s the most controversial statement? For most Americans, it is probably that “gun availability should be regulated.” This is probably the conclusion. Just for fun lets try out the other heuristics. Heuristic #2 says we should find a statement that takes a position on an issue. Hmmm… the issue seems to be gun control, and the arguer takes a position. Both heuristics converge on “gun availability should be regulated.” Heuristic #3 says the conclusion will usually be the first or last statement. Guess what? Same result as the other heuristics. Heuristic #4. A: Gun availability should be regulated because people with easy access to guns are more likely to kill you. Or B: People with easy access to guns are more likely to kill you because gun availability should be regulated. A is the winner. The conclusion in this argument is well established. It follows that what’s left over are premises (support for the conclusion): (P1) If your fellow citizens have easy access to guns, they’re more likely to kill you than if they don’t have access. (P2) Studies show that P1 is true, not just for the twenty-six developed countries analyzed, but on a State-to-State level too. (C) G un availability should be regulated. Example 2 If you make gun ownership a crime, then only criminals will have guns. This means only “bad” guys would have guns, while good people would by definition be at a disadvantage. Gun control is a bad idea. Heuristic #1: What’s the most controversial statement? Probably “gun control is a bad idea.” Heuristic #2: Which statement takes a position on an issue? “Gun control is a bad idea.” Heuristic #3: “Gun control is a bad idea” is last and also passed heuristic 1 and 2. Probably a good bet as the conclusion. Heuristic #4: A: If you make gun ownership a crime, then only criminals will have guns because gun control is a bad idea.

B: Gun control is a bad idea because if you make gun ownership a crime, then only criminals will have guns.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Published by philosophami

Philosopher, judoka, coach, traveller, hiker, dancer, and dog-lover. View all posts by philosophami

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better by

Get full access to An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better and 60K+ other titles, with a free 10-day trial of O'Reilly.

There are also live events, courses curated by job role, and more.

IDENTIFYING ARGUMENTS

8.1 WHAT IS AN ARGUMENT?

In ordinary usage, an argument is often taken to be a somewhat heated dispute between people. But in logic and critical thinking, an argument is a list of statements, one of which is the conclusion and the others are the premises or assumptions of the argument. An example:

It is raining.

So you should bring an umbrella.

In this argument, the first statement is the premise and the second one the conclusion. The premises of an argument are offered as reasons for accepting the conclusion. It is therefore irrational to accept an argument as a good one and yet refuse to accept the conclusion. Giving reasons is a central part of critical thinking. It is not the same as simply expressing an opinion. If you say “that dress looks nice,” you are only expressing an opinion. But if you say “that dress looks nice because the design is very elegant,” then it would be an argument indeed. Dogmatic people tend to make assertions without giving arguments. When they cannot defend themselves, they often resort to responses such as “this is a matter of opinion,” “this is just what you think,” or “I have the right to believe whatever I want.”

The ability to construct, identify, and evaluate arguments is a crucial part of critical thinking. Giving good arguments helps us convince other people, and improve our presentation and debating skills. More important, using arguments to support our beliefs with reasons is likely to help us discover the ...

Get An Introduction to Critical Thinking and Creativity: Think More, Think Better now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.

Don’t leave empty-handed

Get Mark Richards’s Software Architecture Patterns ebook to better understand how to design components—and how they should interact.

It’s yours, free.

Check it out now on O’Reilly

Dive in for free with a 10-day trial of the O’Reilly learning platform—then explore all the other resources our members count on to build skills and solve problems every day.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8 Arguments and Critical Thinking

J. anthony blair, introduction [1].

This chapter discusses two different conceptions of argument, and then discusses the role of arguments in critical thinking. It is followed by a chapter in which David Hitchcock carefully analyses one common concept of an argument.

1. Two meanings of ‘argument’

The word ‘argument’ is used in a great many ways. Any thorough understanding of arguments requires understanding ‘argument’ in each of its senses or uses. These may be divided into two large groupings: arguments had or engaged in , and arguments made or used . I begin with the former.

1.1 A n ‘a rgument’ as something two parties have with each othe r, something they get into, the kind of ‘argument’ one has in mind in de scribing two people as “arguing all the time ”

For many people outside academia or the practice of law, an argument is a quarrel . It is usually a verbal quarrel, but it doesn’t have to use words. If dishes are flying or people are glaring at each other in angry silence, it can still be an argument. What makes a quarrel an argument is that it involves a communication between two or more parties (however dysfunctional the communication may be) in which the parties disagree and in which that disagreement and reasons, actual or alleged, motivating it are expressed—usually in words or other communicative gestures.

Quarrels are emotional. The participants experience and express emotions, although that feature is not exclusive to arguments that are quarrels. People can and do argue emotionally, and (or) when inspired by strong emotions, when they are not quarrelling. Heated arguments are not necessarily quarrels; but quarrels tend to be heated.

What makes quarrels emotional in some cases is that at least one party experiences the disagreement as representing some sort of personal attack, and so experiences his or her ego or sense of self-worth as being threatened. Fear is a reaction to a perceived threat, and anger is a way of coping with fear and also with embarrassment and shame. In other cases, the argument about the ostensible disagreement is a reminder of or a pretext for airing another, deeper grievance. Jealousy and resentment fuel quarrels. Traces of ego-involvement often surface even in what are supposed to be more civilized argumentative exchanges, such as scholarly disputes. Quarrels tend not to be efficient ways of resolving the disagreements that gives rise to them because the subject of a disagreement changes as the emotional attacks escalate or because the quarrel was often not really about that ostensible disagreement in the first place.

In teaching that ‘argument’ has different senses, it is misleading to leave the impression (as many textbooks do) that quarrels are the only species of argument of this genus. In fact they are just one instance of a large class of arguments in this sense of extended, expressed, disagreements between or among two or more parties.

A dispute is an argument in this sense that need not be a quarrel. It is a disagreement between usually two parties about the legality, or morality, or the propriety on some other basis, of a particular act or policy. It can be engaged in a civil way by the disputants or their proxies (e.g., their spokespersons or their lawyers). Sometimes only the disputing parties settle their difference; sometimes a third party such as a mediator, arbitrator or judge is called in to impose a settlement.

A debate is another argument of this general kind. Debates are more or less formalized or regimented verbal exchanges between parties who might disagree, but in any case who take up opposing sides on an issue. Procedural rules that govern turn-taking, time available for each turn, and topics that may be addressed are agreed to when political opponents debate one another. Strict and precise rules of order govern who may speak, who must be addressed, sometimes time limits for interventions, in parliamentary or congressional debates in political decision-making bodies, or in formal intercollegiate competitive debates. Usually the “opponent” directly addressed in the debate is not the party that each speaker is trying to influence, so although the expressed goal is to “win” the debate, winning does not entail getting the opponent to concede. Instead, it calls for convincing an on-looking party or audience—the judge of the debate or the jury in a courtroom or the television audience or the press or the electorate as a whole—of the superior merits of one’s case for the opinion being argued for in the debate.

To be distinguished from a debate and a dispute by such factors as scale is a controversy . Think of such issues as the abortion controversy, the climate change controversy, the same-sex marriage controversy, the LGBT rights controversy, the animal rights controversy. The participants are many—often millions. The issues are complex and there are many disputes about details involved, including sometimes even formal debates between representatives of different sides. Typically there is a range of positions, and there might be several different sides each with positions that vary one from another. A controversy typically occurs over an extended period of time, often years and sometime decades long. But an entire controversy can be called an argument, as in, “the argument over climate change.” Controversies tend to be unregulated, unlike debates but like quarrels, although they need not be particularly angry even when they are emotional. Like quarrels, and unlike debates, the conditions under which controversies occur, including any constraints on them, are shaped by the participants.

Somewhere among quarrels, debates and controversies lie the theoretical arguments that theorists in academic disciplines engage in, in academic journals and scholarly monographs. In such arguments theorists take positions, sometimes siding with others and sometimes standing alone, and they argue back and forth about which theoretical position is the correct one. In a related type of argument, just two people argue back and forth about what is the correct position on some issue (including meta-level arguments about what is the correct way to frame the issue in the first place).

The stakes don’t have to be theories and the participants don’t have to be academics. Friends argue about which team will win the championship, where the best fishing spot is located, or what titles to select for the book club. Family members argue about how to spend their income, what school to send the children to, or whether a child is old enough to go on a date without a chaperone. Co-workers argue about the best way to do a job, whether to change service providers, whether to introduce a new product line, and so on. These arguments are usually amicable, whether or not they settle the question in dispute.

All of these kinds of “argument” in this sense of the term—quarrels, friendly disputes, arguments at work, professional arguments about theoretical positions, formal or informal debates, and various kinds of controversy—share several features.

- They involve communications between or among two or more people. Something initiates the communication, and either something ends it or there are ways for participants to join and to exit the conversation. They entail turn-taking (less or more regimented), each side addressing the other side and in turn construing and assessing what the other has to say in reply and formulating and communicating a response to the replies of the other side. And, obviously, they involve the expression, usually verbal, of theses and of reasons for them or against alternatives and criticisms.

- They have a telos or aim, although there seems to be no single end in mind for all of them or even for each of them. In a quarrel the goal might be to have one’s point of view prevail, to get one’s way, but it might instead (or in addition) be to humiliate the other person or to save one’s own self-respect. Some quarrels—think of the ongoing bickering between some long-married spouses—seem to be a way for two people to communicate, merely to acknowledge one another. In a debate, each side seeks to “win,” which can mean different things in different contexts ( cf. a collegiate debate vs. a debate between candidates in an election vs. a parliamentary debate). Some arguments seemed designed to convince the other to give up his position or accept the interlocutor’s position, or to get the other to act in some way or to adopt some policy. Some have the more modest goal of getting a new issue recognized for future deliberation and debate. Still others are clearly aimed not at changing anyone’s mind but at reinforcing or entrenching a point of view already held (as is usually the case with religious sermons or with political speeches to the party faithful). Some are intended to establish or to demonstrate the truth or reasonableness of some position or recommendation and (perhaps) also to get others to “see” that the truth has been established. Some seem designed to maintain disagreement, as when representatives of competing political parties argue with one another.

- All these various kinds of argument are more or less extended, both in the sense that they occur over time, sometimes long stretches of time, and also in the sense that they typically involved many steps: extensive and complex support for a point of view and critique of its alternatives.

- In nearly every case, the participants give reasons for the claims they make and they expect the other participants in the argument to give reasons for their claims. This is even a feature of quarrels, at least at the outset, although such arguments can deteriorate into name-calling and worse. (Notice that even the “yes you did; no I didn’t;…; did; didn’t” sequence of the Monty Python “Having an argument” skit breaks down and a reason is sought.)

The kinds of argument listed so far are all versions of having an argument (see Daniel J. O’Keefe, 1977, 1982). Some might think that this is not the sense of ‘argument’ that is pertinent to critical thinking instruction, but such arguments are the habitat of the kinds of argument that critical thinkers need to be able to identify, analyze and evaluate.

1.2 An argument a s something a person makes (or constructs, invents, borrows) consisting of purported reasons alleged to suggest, or support or prove a point and that is used for some purpose such as to persuade someone of some claim, to justify someone in maintaining the position claimed, or to test a claim .

When people have arguments—when they engage in one or another of the activities of arguing described above—one of the things they routinely do is present or allege or offer reasons in support of the claims that they advance, defend, challenge, dispute, question, or consider. That is, in having “arguments,” we typically make and use “arguments.” The latter obviously have to be arguments in different sense from the former. They are often called “reason-claim” complexes. If arguments that someone has had constitute a type of communication or communicative activity, arguments that someone has made or used are actual or potential contributions to such activities. Reason-claim complexes are typically made and used when engaged in an argument in the first sense, trying to convince someone of your point of view during a disagreement or dispute with them. Here is a list of some of the many definitions found in textbooks of ‘argument’ in this second sense.

“… here [the word ‘argument’] … is used in the … logical sense of giving reasons for or against some claim.” Understanding Arguments, Robert Fogelin and Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, 6th ed., p. 1. “Thus an argument is a discourse that contains at least two statements, one of which is asserted to be a reason for the other.” Monroe Beardsley, Practical Logic, p. 9. “An argument is a set of claims a person puts forward in an attempt to show that some further claim is rationally acceptable.” Trudy Govier. A Practical Study of Arguments, 5th ed., p. 3. An argument is “a set of clams some of which are presented as reasons for accepting some further claim.” Alec Fisher, Critical Thinking, An Introduction, p. 235. Argument: “A conclusion about an issue that is supported by reasons.” Sherry Diestler, Becoming a Critical Thinker, 4th ed., p. 403. “ Argument: An attempt to support a conclusion by giving reasons for it.” Robert Ennis, Critical Thinking, p. 396. “Argument – A form of thinking in which certain statements (reasons) are offered in support of another statement (conclusion).” John Chaffee, Thinking Critically, p. 415 “When we use the word argument in this book we mean a message which attempts to establish a statement as true or worthy of belief on the basis of other statements.” James B. Freeman, Thinking Logically, p. 20 “Argument. A sequence of propositions intended to establish the truth of one of the propositions.” Richard Feldman, Reason and Argument, p. 447. “Arguments consist of conclusions and reasons for them, called ‘premises’.” Wayne Grennan, Argument Evaluation, p. 5. Argument: “A set of claims, one of which, the conclusion is supported by [i.e., is supposed to provide a reason for] one or more of the other claims. Reason in the Balance, Sharon Bailin & Mark Battersby, p. 41.

These are not all compatible, and most of them define ‘argument’ using other terms—‘reasons’, ‘claims’, ‘propositions’, ‘statements’, ‘premises’ and ‘conclusions’—that are in no less need of definition than it is. In the next chapter, David Hitchcock offers a careful analysis of this concept of an argument.