- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- See Success Stories

- Access Free Resources

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

Identifying a Research Problem: A Step-by-Step Guide

The first and perhaps most important step in the research process is identifying a research problem. This step sets the foundation for all subsequent research activities and largely determines the success of your scholarly work.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the steps involved in identifying a research problem, from understanding its essence to employing advanced strategies for refinement.

Key Takeaways

- Remember: Grasping the definition and importance of a research problem isn't just a step—it's crucial for your academic success.

- Exploring various sources, like literature reviews and expert consultations, can guide you in formulating a solid research problem.

- A clear problem statement, aligned research objectives, and well-defined questions are crucial for a focused study.

- Evaluating the feasibility and potential impact of a research problem ensures its relevance and scope.

- Advanced strategies, including interdisciplinary approaches and technology utilization, can enhance the identification and refinement of research problems.

Understanding the Essence of Identifying a Research Problem

Defining the research problem.

A research problem is the focal point of any academic inquiry. It is a concise and well-defined statement that outlines the specific issue or question that the research aims to address. This research problem usually sets the tone for the entire study and provides you, the researcher, with a clear purpose and a clear direction on how to go about conducting your research.

Importance in Academic Research

It also demonstrates the significance of your research and its potential to contribute new knowledge to the existing body of literature in the world. A compelling research problem not only captivates the attention of your peers but also lays the foundation for impactful and meaningful research outcomes.

Initial Steps to Identification

To identify a research problem, you need a systematic approach and a deep understanding of the subject area. Below are some steps to guide you in this process:

- Conduct a thorough literature review to understand what has been studied before.

- Identify gaps in the existing research that could form the basis of your study.

- Consult with academic mentors to refine your ideas and approach.

Exploring Sources for Research Problem Identification

Literature review.

When you embark on the journey of identifying a research problem, a thorough literature review is indispensable. This process involves scrutinizing existing research to find literature gaps and unexplored areas that could form the basis of your research. It's crucial to analyze recent studies, seminal works, and review articles to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the topic.

Existing Theories and Frameworks

The exploration of existing theories and frameworks provides a solid foundation for developing a research problem. By understanding the established models and theories, you can identify inconsistencies or areas lacking in depth which might offer fruitful avenues for research.

Consultation with Academic Mentors

Engaging with academic mentors is vital in shaping a well-defined research problem. Their expertise can guide you through the complexities of your field, offering insights into feasible research questions and helping you refine your focus. This interaction often leads to the identification of unique and significant research opportunities that align with current academic and industry trends.

Formulating the Research Problem

Crafting a clear problem statement.

To effectively address your research problem, start by crafting a clear problem statement . This involves succinctly describing who is affected by the problem, why it is important, and how your research will contribute to solving it. Ensure your problem statement is concise and specific to guide the entire research process.

Setting Research Objectives

Setting clear research objectives is crucial for maintaining focus throughout your study. These objectives should directly align with the problem statement and guide your research activities. Consider using a bulleted list to outline your main objectives:

- Understand the underlying factors contributing to the problem

- Explore potential solutions

- Evaluate the effectiveness of proposed solutions

Determining Research Questions

The formulation of precise research questions is a pivotal step in defining the scope and direction of your study. These questions should be directly derived from your research objectives and designed to be answerable through your chosen research methods. Crafting well-defined research questions will help you maintain a clear focus and avoid common pitfalls in the research process.

How to Evaluate the Scope and Relevance of Your Research Problem

Feasibility assessment.

Before you finalize a research problem, it is crucial to assess its feasibility. Consider the availability of resources, time, and expertise required to conduct the research. Evaluate potential constraints and determine if the research problem can be realistically tackled within the given limitations.

Significance to the Field

Ask yourself: Does my research problem have a clear and direct impact on my field? How will it contribute to advancing knowledge? It should aim to contribute to existing knowledge and address a real-world issue that is relevant to your academic discipline.

Potential Impact on Existing Knowledge

The potential impact of your research problem on existing knowledge cannot be understated. It should challenge, extend, or refine current understanding in a meaningful way. Consider how your research can add value to the existing body of work and potentially lead to significant advancements in your field.

Techniques for Refining the Research Problem

Narrowing down the focus.

To effectively refine your research problem, start by narrowing down the focus . This involves pinpointing the specific aspects of your topic that are most significant and ensuring that your research problem is not too broad. This targeted approach helps in identifying knowledge gaps and formulating more precise research questions.

Incorporating Feedback

Feedback is crucial in the refinement process. Engage with academic mentors, peers, and experts in your field to gather insights and suggestions. This collaborative feedback can lead to significant improvements in your research problem, making it more robust and relevant.

Iterative Refinement Process

Refinement should be seen as an iterative process, where you continuously refine and revise your research problem based on new information and feedback. This approach ensures that your research problem remains aligned with current trends and academic standards, ultimately enhancing its feasibility and relevance.

Challenges in Identifying a Research Problem

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

Identifying a research problem can be fraught with common pitfalls such as selecting a topic that is too broad or too narrow. To avoid these, you should conduct a thorough literature review and seek feedback from peers and mentors. This proactive approach ensures that your research question is both relevant and manageable.

Dealing with Ambiguity

Ambiguity in defining the research problem can lead to significant challenges down the line. Ensure clarity by operationalizing variables and explicitly stating the research objectives. This clarity will guide your entire research process, making it more structured and focused.

Balancing Novelty and Practicality

While it's important to address a novel issue in your research, practicality should not be overlooked. A research problem should not only contribute new knowledge but also be feasible and have clear implications. Balancing these aspects often requires iterative refinement and consultation with academic mentors to align your research with real-world applications.

Advanced Strategies for Identifying a Research Problem

Interdisciplinary approaches.

Embrace the power of interdisciplinary approaches to uncover unique and comprehensive research problems. By integrating knowledge from various disciplines, you can address complex issues that single-field studies might overlook. This method not only broadens the scope of your research but also enhances its applicability and depth.

Utilizing Technology and Data Analytics

Leverage technology and data analytics to refine and identify research problems with precision. Advanced tools like machine learning and big data analysis can reveal patterns and insights that traditional methods might miss. This approach is particularly useful in fields where large datasets are involved, or where real-time data integration can lead to more dynamic research outcomes.

Engaging with Industry and Community Needs

Focus on the needs of industry and community to ensure your research is not only academically sound but also practically relevant. Engaging with real-world problems can provide a rich source of research questions that are directly applicable and beneficial to society. This strategy not only enhances the relevance of your research but also increases its potential for impact.

Dive into the world of academic success with our 'Advanced Strategies for Identifying a Research Problem' at Research Rebels. Our expertly crafted guides and action plans are designed to simplify your thesis journey, transforming complex academic challenges into manageable tasks. Don't wait to take control of your academic future. Visit our website now to learn more and claim your special offer!

Struggling to Navigate the Complexities of Identifying a Research Problem?

- Quickly identify valuable research gaps.

- Develop clear and impactful problem statements.

- Align your research objectives with precise, answerable questions.

- Streamline your research planning process, saving time and reducing stress.

Ready to take control of your research journey? Get the Research Proposal Compass now and lay the groundwork for academic success.

In conclusion, identifying a research problem is a foundational step in the academic research process that requires careful consideration and systematic approach. This guide has outlined the essential steps involved, from understanding the context and reviewing existing literature to formulating clear research questions. By adhering to these guidelines, researchers can ensure that their studies are grounded in a well-defined problem, enhancing the relevance and impact of their findings. It is crucial for scholars to approach this task with rigor and critical thinking to contribute meaningfully to the body of knowledge in their respective fields.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a research problem.

A research problem is a specific issue, inconsistency, or gap in knowledge that needs to be addressed through scientific inquiry. It forms the foundation of a research study, guiding the research questions, methodology, and analysis.

Why is identifying a research problem important?

Identifying a research problem is crucial as it determines the direction and scope of the study. It helps researchers focus their inquiry, formulate hypotheses, and contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

How do I identify a suitable research problem?

To identify a suitable research problem, start with a thorough literature review to understand existing research and identify gaps. Consult with academic mentors, and consider relevance, feasibility, and your own interests.

What are some common pitfalls in identifying a research problem?

Common pitfalls include choosing a problem that is too broad or too narrow, not aligning with existing literature, lack of originality, and failing to consider the practical implications and feasibility of the study.

Can technology help in identifying a research problem?

Yes, technology and data analytics can aid in identifying research problems by providing access to a vast amount of data, revealing patterns and trends that might not be visible otherwise. Tools like digital libraries and research databases are particularly useful.

How can I refine my research problem?

Refine your research problem by narrowing its focus, seeking feedback from peers and mentors, and continually reviewing and adjusting the problem statement based on new information and insights gained during preliminary research.

Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics: A Fun and Informative Guide

Unlocking the Power of Data: A Review of 'Essentials of Modern Business Statistics with Microsoft Excel'

Discovering Statistics Using SAS: A Comprehensive Review

Why AI is the Key to Unlocking Your Full Research Potential

Master’s Thesis Research Overload? How to Find the Best Sources—Fast

Abstract vs. Introduction: Which One Sets the Tone for Your Thesis?

Thesis Action Plan

- Rebels Blog

- Blog Articles

- Affiliate Program

- Terms and Conditions

- Payment and Shipping Terms

- Privacy Policy

- Return Policy

© 2024 Research Rebels, All rights reserved.

Your cart is currently empty.

The Research Problem & Statement

I f you’re new to academic research, you’re bound to encounter the concept of a “ research problem ” or “ problem statement ” fairly early in your learning journey. Having a good research problem is essential, as it provides a foundation for developing high-quality research, from relatively small research papers to a full-length PhD dissertations and theses.

In this post, we’ll unpack what a research problem is and how it’s related to a problem statement . We’ll also share some examples and provide a step-by-step process you can follow to identify and evaluate study-worthy research problems for your own project.

Overview: Research Problem 101

What is a research problem.

- What is a problem statement?

Where do research problems come from?

- How to find a suitable research problem

- Key takeaways

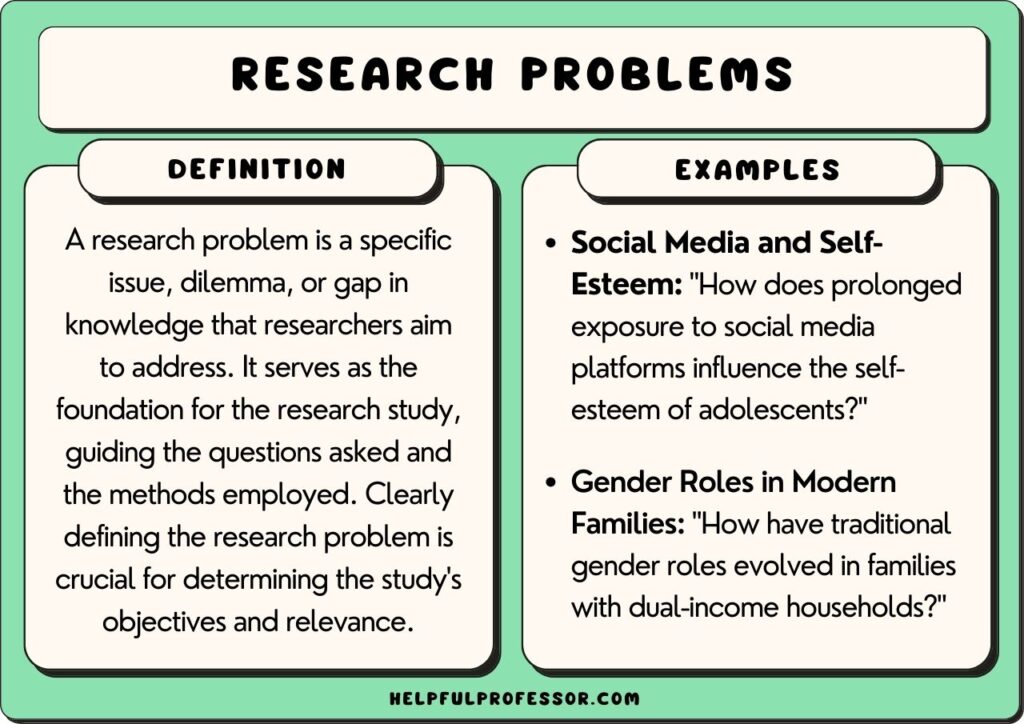

A research problem is, at the simplest level, the core issue that a study will try to solve or (at least) examine. In other words, it’s an explicit declaration about the problem that your dissertation, thesis or research paper will address. More technically, it identifies the research gap that the study will attempt to fill (more on that later).

Let’s look at an example to make the research problem a little more tangible.

To justify a hypothetical study, you might argue that there’s currently a lack of research regarding the challenges experienced by first-generation college students when writing their dissertations [ PROBLEM ] . As a result, these students struggle to successfully complete their dissertations, leading to higher-than-average dropout rates [ CONSEQUENCE ]. Therefore, your study will aim to address this lack of research – i.e., this research problem [ SOLUTION ].

A research problem can be theoretical in nature, focusing on an area of academic research that is lacking in some way. Alternatively, a research problem can be more applied in nature, focused on finding a practical solution to an established problem within an industry or an organisation. In other words, theoretical research problems are motivated by the desire to grow the overall body of knowledge , while applied research problems are motivated by the need to find practical solutions to current real-world problems (such as the one in the example above).

As you can probably see, the research problem acts as the driving force behind any study , as it directly shapes the research aims, objectives and research questions , as well as the research approach. Therefore, it’s really important to develop a very clearly articulated research problem before you even start your research proposal . A vague research problem will lead to unfocused, potentially conflicting research aims, objectives and research questions .

What is a research problem statement?

As the name suggests, a problem statement (within a research context, at least) is an explicit statement that clearly and concisely articulates the specific research problem your study will address. While your research problem can span over multiple paragraphs, your problem statement should be brief , ideally no longer than one paragraph . Importantly, it must clearly state what the problem is (whether theoretical or practical in nature) and how the study will address it.

Here’s an example of a statement of the problem in a research context:

Rural communities across Ghana lack access to clean water, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses and infant mortality. Despite this, there is little research investigating the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects within the Ghanaian context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of such projects in improving access to clean water and reducing rates of waterborne illnesses in these communities.

As you can see, this problem statement clearly and concisely identifies the issue that needs to be addressed (i.e., a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects) and the research question that the study aims to answer (i.e., are community-led water supply projects effective in reducing waterborne illnesses?), all within one short paragraph.

Need a helping hand?

Wherever there is a lack of well-established and agreed-upon academic literature , there is an opportunity for research problems to arise, since there is a paucity of (credible) knowledge. In other words, research problems are derived from research gaps . These gaps can arise from various sources, including the emergence of new frontiers or new contexts, as well as disagreements within the existing research.

Let’s look at each of these scenarios:

New frontiers – new technologies, discoveries or breakthroughs can open up entirely new frontiers where there is very little existing research, thereby creating fresh research gaps. For example, as generative AI technology became accessible to the general public in 2023, the full implications and knock-on effects of this were (or perhaps, still are) largely unknown and therefore present multiple avenues for researchers to explore.

New contexts – very often, existing research tends to be concentrated on specific contexts and geographies. Therefore, even within well-studied fields, there is often a lack of research within niche contexts. For example, just because a study finds certain results within a western context doesn’t mean that it would necessarily find the same within an eastern context. If there’s reason to believe that results may vary across these geographies, a potential research gap emerges.

Disagreements – within many areas of existing research, there are (quite naturally) conflicting views between researchers, where each side presents strong points that pull in opposing directions. In such cases, it’s still somewhat uncertain as to which viewpoint (if any) is more accurate. As a result, there is room for further research in an attempt to “settle” the debate.

Of course, many other potential scenarios can give rise to research gaps, and consequently, research problems, but these common ones are a useful starting point. If you’re interested in research gaps, you can learn more here .

How to find a research problem

Given that research problems flow from research gaps , finding a strong research problem for your research project means that you’ll need to first identify a clear research gap. Below, we’ll present a four-step process to help you find and evaluate potential research problems.

If you’ve read our other articles about finding a research topic , you’ll find the process below very familiar as the research problem is the foundation of any study . In other words, finding a research problem is much the same as finding a research topic.

Step 1 – Identify your area of interest

Naturally, the starting point is to first identify a general area of interest . Chances are you already have something in mind, but if not, have a look at past dissertations and theses within your institution to get some inspiration. These present a goldmine of information as they’ll not only give you ideas for your own research, but they’ll also help you see exactly what the norms and expectations are for these types of projects.

At this stage, you don’t need to get super specific. The objective is simply to identify a couple of potential research areas that interest you. For example, if you’re undertaking research as part of a business degree, you may be interested in social media marketing strategies for small businesses, leadership strategies for multinational companies, etc.

Depending on the type of project you’re undertaking, there may also be restrictions or requirements regarding what topic areas you’re allowed to investigate, what type of methodology you can utilise, etc. So, be sure to first familiarise yourself with your institution’s specific requirements and keep these front of mind as you explore potential research ideas.

Step 2 – Review the literature and develop a shortlist

Once you’ve decided on an area that interests you, it’s time to sink your teeth into the literature . In other words, you’ll need to familiarise yourself with the existing research regarding your interest area. Google Scholar is a good starting point for this, as you can simply enter a few keywords and quickly get a feel for what’s out there. Keep an eye out for recent literature reviews and systematic review-type journal articles, as these will provide a good overview of the current state of research.

At this stage, you don’t need to read every journal article from start to finish . A good strategy is to pay attention to the abstract, intro and conclusion , as together these provide a snapshot of the key takeaways. As you work your way through the literature, keep an eye out for what’s missing – in other words, what questions does the current research not answer adequately (or at all)? Importantly, pay attention to the section titled “ further research is needed ”, typically found towards the very end of each journal article. This section will specifically outline potential research gaps that you can explore, based on the current state of knowledge (provided the article you’re looking at is recent).

Take the time to engage with the literature and develop a big-picture understanding of the current state of knowledge. Reviewing the literature takes time and is an iterative process , but it’s an essential part of the research process, so don’t cut corners at this stage.

As you work through the review process, take note of any potential research gaps that are of interest to you. From there, develop a shortlist of potential research gaps (and resultant research problems) – ideally 3 – 5 options that interest you.

Step 3 – Evaluate your potential options

Once you’ve developed your shortlist, you’ll need to evaluate your options to identify a winner. There are many potential evaluation criteria that you can use, but we’ll outline three common ones here: value, practicality and personal appeal.

Value – a good research problem needs to create value when successfully addressed. Ask yourself:

- Who will this study benefit (e.g., practitioners, researchers, academia)?

- How will it benefit them specifically?

- How much will it benefit them?

Practicality – a good research problem needs to be manageable in light of your resources. Ask yourself:

- What data will I need access to?

- What knowledge and skills will I need to undertake the analysis?

- What equipment or software will I need to process and/or analyse the data?

- How much time will I need?

- What costs might I incur?

Personal appeal – a research project is a commitment, so the research problem that you choose needs to be genuinely attractive and interesting to you. Ask yourself:

- How appealing is the prospect of solving this research problem (on a scale of 1 – 10)?

- Why, specifically, is it attractive (or unattractive) to me?

- Does the research align with my longer-term goals (e.g., career goals, educational path, etc)?

Depending on how many potential options you have, you may want to consider creating a spreadsheet where you numerically rate each of the options in terms of these criteria. Remember to also include any criteria specified by your institution . From there, tally up the numbers and pick a winner.

Step 4 – Craft your problem statement

Once you’ve selected your research problem, the final step is to craft a problem statement. Remember, your problem statement needs to be a concise outline of what the core issue is and how your study will address it. Aim to fit this within one paragraph – don’t waffle on. Have a look at the problem statement example we mentioned earlier if you need some inspiration.

Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- A research problem is an explanation of the issue that your study will try to solve. This explanation needs to highlight the problem , the consequence and the solution or response.

- A problem statement is a clear and concise summary of the research problem , typically contained within one paragraph.

- Research problems emerge from research gaps , which themselves can emerge from multiple potential sources, including new frontiers, new contexts or disagreements within the existing literature.

- To find a research problem, you need to first identify your area of interest , then review the literature and develop a shortlist, after which you’ll evaluate your options, select a winner and craft a problem statement .

You Might Also Like:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Dissertation While Working: A How-To Guide

Struggling to balance your dissertation with a full-time job and family? Learn practical strategies to achieve success.

How To Review & Understand Academic Literature Quickly

Learn how to fast-track your literature review by reading with intention and clarity. Dr E and Amy Murdock explain how.

Dissertation Writing Services: Far Worse Than You Think

Thinking about using a dissertation or thesis writing service? You might want to reconsider that move. Here’s what you need to know.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

I APPRECIATE YOUR CONCISE AND MIND-CAPTIVATING INSIGHTS ON THE STATEMENT OF PROBLEMS. PLEASE I STILL NEED SOME SAMPLES RELATED TO SUICIDES.

Very pleased and appreciate clear information.

Your videos and information have been a life saver for me throughout my dissertation journey. I wish I’d discovered them sooner. Thank you!

Very interesting. Thank you. Please I need a PhD topic in climate change in relation to health.

Your posts have provided a clear, easy to understand, motivating literature, mainly when these topics tend to be considered “boring” in some careers.

Thank you, but i am requesting for a topic in records management

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

45 Research Problem Examples & Inspiration

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A research problem is an issue of concern that is the catalyst for your research. It demonstrates why the research problem needs to take place in the first place.

Generally, you will write your research problem as a clear, concise, and focused statement that identifies an issue or gap in current knowledge that requires investigation.

The problem will likely also guide the direction and purpose of a study. Depending on the problem, you will identify a suitable methodology that will help address the problem and bring solutions to light.

Research Problem Examples

In the following examples, I’ll present some problems worth addressing, and some suggested theoretical frameworks and research methodologies that might fit with the study. Note, however, that these aren’t the only ways to approach the problems. Keep an open mind and consult with your dissertation supervisor!

Psychology Problems

1. Social Media and Self-Esteem: “How does prolonged exposure to social media platforms influence the self-esteem of adolescents?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Comparison Theory

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking adolescents’ social media usage and self-esteem measures over time, combined with qualitative interviews.

2. Sleep and Cognitive Performance: “How does sleep quality and duration impact cognitive performance in adults?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Psychology

- Methodology : Experimental design with controlled sleep conditions, followed by cognitive tests. Participant sleep patterns can also be monitored using actigraphy.

3. Childhood Trauma and Adult Relationships: “How does unresolved childhood trauma influence attachment styles and relationship dynamics in adulthood?

- Theoretical Framework : Attachment Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of attachment styles with qualitative in-depth interviews exploring past trauma and current relationship dynamics.

4. Mindfulness and Stress Reduction: “How effective is mindfulness meditation in reducing perceived stress and physiological markers of stress in working professionals?”

- Theoretical Framework : Humanist Psychology

- Methodology : Randomized controlled trial comparing a group practicing mindfulness meditation to a control group, measuring both self-reported stress and physiological markers (e.g., cortisol levels).

5. Implicit Bias and Decision Making: “To what extent do implicit biases influence decision-making processes in hiring practices?

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design using Implicit Association Tests (IAT) to measure implicit biases, followed by simulated hiring tasks to observe decision-making behaviors.

6. Emotional Regulation and Academic Performance: “How does the ability to regulate emotions impact academic performance in college students?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Theory of Emotion

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys measuring emotional regulation strategies, combined with academic performance metrics (e.g., GPA).

7. Nature Exposure and Mental Well-being: “Does regular exposure to natural environments improve mental well-being and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression?”

- Theoretical Framework : Biophilia Hypothesis

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing mental health measures of individuals with regular nature exposure to those without, possibly using ecological momentary assessment for real-time data collection.

8. Video Games and Cognitive Skills: “How do action video games influence cognitive skills such as attention, spatial reasoning, and problem-solving?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cognitive Load Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design with pre- and post-tests, comparing cognitive skills of participants before and after a period of action video game play.

9. Parenting Styles and Child Resilience: “How do different parenting styles influence the development of resilience in children facing adversities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Baumrind’s Parenting Styles Inventory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of resilience and parenting styles with qualitative interviews exploring children’s experiences and perceptions.

10. Memory and Aging: “How does the aging process impact episodic memory , and what strategies can mitigate age-related memory decline?

- Theoretical Framework : Information Processing Theory

- Methodology : Cross-sectional study comparing episodic memory performance across different age groups, combined with interventions like memory training or mnemonic strategies to assess potential improvements.

Education Problems

11. Equity and Access : “How do socioeconomic factors influence students’ access to quality education, and what interventions can bridge the gap?

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Pedagogy

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative data on student outcomes with qualitative interviews and focus groups with students, parents, and educators.

12. Digital Divide : How does the lack of access to technology and the internet affect remote learning outcomes, and how can this divide be addressed?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Construction of Technology Theory

- Methodology : Survey research to gather data on access to technology, followed by case studies in selected areas.

13. Teacher Efficacy : “What factors contribute to teacher self-efficacy, and how does it impact student achievement?”

- Theoretical Framework : Bandura’s Self-Efficacy Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys to measure teacher self-efficacy, combined with qualitative interviews to explore factors affecting it.

14. Curriculum Relevance : “How can curricula be made more relevant to diverse student populations, incorporating cultural and local contexts?”

- Theoretical Framework : Sociocultural Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of curricula, combined with focus groups with students and teachers.

15. Special Education : “What are the most effective instructional strategies for students with specific learning disabilities?

- Theoretical Framework : Social Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional strategies, with pre- and post-tests to measure student achievement.

16. Dropout Rates : “What factors contribute to high school dropout rates, and what interventions can help retain students?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking students over time, combined with interviews with dropouts.

17. Bilingual Education : “How does bilingual education impact cognitive development and academic achievement?

- Methodology : Comparative study of students in bilingual vs. monolingual programs, using standardized tests and qualitative interviews.

18. Classroom Management: “What reward strategies are most effective in managing diverse classrooms and promoting a positive learning environment?

- Theoretical Framework : Behaviorism (e.g., Skinner’s Operant Conditioning)

- Methodology : Observational research in classrooms , combined with teacher interviews.

19. Standardized Testing : “How do standardized tests affect student motivation, learning, and curriculum design?”

- Theoretical Framework : Critical Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative analysis of test scores and student outcomes, combined with qualitative interviews with educators and students.

20. STEM Education : “What methods can be employed to increase interest and proficiency in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) fields among underrepresented student groups?”

- Theoretical Framework : Constructivist Learning Theory

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing different instructional methods, with pre- and post-tests.

21. Social-Emotional Learning : “How can social-emotional learning be effectively integrated into the curriculum, and what are its impacts on student well-being and academic outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Goleman’s Emotional Intelligence Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of student well-being with qualitative interviews.

22. Parental Involvement : “How does parental involvement influence student achievement, and what strategies can schools use to increase it?”

- Theoretical Framework : Reggio Emilia’s Model (Community Engagement Focus)

- Methodology : Survey research with parents and teachers, combined with case studies in selected schools.

23. Early Childhood Education : “What are the long-term impacts of quality early childhood education on academic and life outcomes?”

- Theoretical Framework : Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

- Methodology : Longitudinal study comparing students with and without early childhood education, combined with observational research.

24. Teacher Training and Professional Development : “How can teacher training programs be improved to address the evolving needs of the 21st-century classroom?”

- Theoretical Framework : Adult Learning Theory (Andragogy)

- Methodology : Pre- and post-assessments of teacher competencies, combined with focus groups.

25. Educational Technology : “How can technology be effectively integrated into the classroom to enhance learning, and what are the potential drawbacks or challenges?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing classrooms with and without specific technologies, combined with teacher and student interviews.

Sociology Problems

26. Urbanization and Social Ties: “How does rapid urbanization impact the strength and nature of social ties in communities?”

- Theoretical Framework : Structural Functionalism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on social ties with qualitative interviews in urbanizing areas.

27. Gender Roles in Modern Families: “How have traditional gender roles evolved in families with dual-income households?”

- Theoretical Framework : Gender Schema Theory

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with dual-income families, combined with historical data analysis.

28. Social Media and Collective Behavior: “How does social media influence collective behaviors and the formation of social movements?”

- Theoretical Framework : Emergent Norm Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of social media platforms, combined with quantitative surveys on participation in social movements.

29. Education and Social Mobility: “To what extent does access to quality education influence social mobility in socioeconomically diverse settings?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking educational access and subsequent socioeconomic status, combined with qualitative interviews.

30. Religion and Social Cohesion: “How do religious beliefs and practices contribute to social cohesion in multicultural societies?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys on religious beliefs and perceptions of social cohesion, combined with ethnographic studies.

31. Consumer Culture and Identity Formation: “How does consumer culture influence individual identity formation and personal values?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Identity Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining content analysis of advertising with qualitative interviews on identity and values.

32. Migration and Cultural Assimilation: “How do migrants negotiate cultural assimilation and preservation of their original cultural identities in their host countries?”

- Theoretical Framework : Post-Structuralism

- Methodology : Qualitative interviews with migrants, combined with observational studies in multicultural communities.

33. Social Networks and Mental Health: “How do social networks, both online and offline, impact mental health and well-being?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Network Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social network characteristics and mental health metrics, combined with qualitative interviews.

34. Crime, Deviance, and Social Control: “How do societal norms and values shape definitions of crime and deviance, and how are these definitions enforced?”

- Theoretical Framework : Labeling Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of legal documents and media, combined with ethnographic studies in diverse communities.

35. Technology and Social Interaction: “How has the proliferation of digital technology influenced face-to-face social interactions and community building?”

- Theoretical Framework : Technological Determinism

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on technology use with qualitative observations of social interactions in various settings.

Nursing Problems

36. Patient Communication and Recovery: “How does effective nurse-patient communication influence patient recovery rates and overall satisfaction with care?”

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing patient satisfaction and recovery metrics, combined with observational studies on nurse-patient interactions.

37. Stress Management in Nursing: “What are the primary sources of occupational stress for nurses, and how can they be effectively managed to prevent burnout?”

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative measures of stress and burnout with qualitative interviews exploring personal experiences and coping mechanisms.

38. Hand Hygiene Compliance: “How effective are different interventions in improving hand hygiene compliance among nursing staff, and what are the barriers to consistent hand hygiene?”

- Methodology : Experimental design comparing hand hygiene rates before and after specific interventions, combined with focus groups to understand barriers.

39. Nurse-Patient Ratios and Patient Outcomes: “How do nurse-patient ratios impact patient outcomes, including recovery rates, complications, and hospital readmissions?”

- Methodology : Quantitative study analyzing patient outcomes in relation to staffing levels, possibly using retrospective chart reviews.

40. Continuing Education and Clinical Competence: “How does regular continuing education influence clinical competence and confidence among nurses?”

- Methodology : Longitudinal study tracking nurses’ clinical skills and confidence over time as they engage in continuing education, combined with patient outcome measures to assess potential impacts on care quality.

Communication Studies Problems

41. Media Representation and Public Perception: “How does media representation of minority groups influence public perceptions and biases?”

- Theoretical Framework : Cultivation Theory

- Methodology : Content analysis of media representations combined with quantitative surveys assessing public perceptions and attitudes.

42. Digital Communication and Relationship Building: “How has the rise of digital communication platforms impacted the way individuals build and maintain personal relationships?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Penetration Theory

- Methodology : Mixed methods, combining quantitative surveys on digital communication habits with qualitative interviews exploring personal relationship dynamics.

43. Crisis Communication Effectiveness: “What strategies are most effective in managing public relations during organizational crises, and how do they influence public trust?”

- Theoretical Framework : Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT)

- Methodology : Case study analysis of past organizational crises, assessing communication strategies used and subsequent public trust metrics.

44. Nonverbal Cues in Virtual Communication: “How do nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions and gestures, influence message interpretation in virtual communication platforms?”

- Theoretical Framework : Social Semiotics

- Methodology : Experimental design using video conferencing tools, analyzing participants’ interpretations of messages with varying nonverbal cues.

45. Influence of Social Media on Political Engagement: “How does exposure to political content on social media platforms influence individuals’ political engagement and activism?”

- Theoretical Framework : Uses and Gratifications Theory

- Methodology : Quantitative surveys assessing social media habits and political engagement levels, combined with content analysis of political posts on popular platforms.

Before you Go: Tips and Tricks for Writing a Research Problem

This is an incredibly stressful time for research students. The research problem is going to lock you into a specific line of inquiry for the rest of your studies.

So, here’s what I tend to suggest to my students:

- Start with something you find intellectually stimulating – Too many students choose projects because they think it hasn’t been studies or they’ve found a research gap. Don’t over-estimate the importance of finding a research gap. There are gaps in every line of inquiry. For now, just find a topic you think you can really sink your teeth into and will enjoy learning about.

- Take 5 ideas to your supervisor – Approach your research supervisor, professor, lecturer, TA, our course leader with 5 research problem ideas and run each by them. The supervisor will have valuable insights that you didn’t consider that will help you narrow-down and refine your problem even more.

- Trust your supervisor – The supervisor-student relationship is often very strained and stressful. While of course this is your project, your supervisor knows the internal politics and conventions of academic research. The depth of knowledge about how to navigate academia and get you out the other end with your degree is invaluable. Don’t underestimate their advice.

I’ve got a full article on all my tips and tricks for doing research projects right here – I recommend reading it:

- 9 Tips on How to Choose a Dissertation Topic

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- QUICK LINKS

- How to enroll

- Career services

How to Identify an Appropriate Research Problem

By Mansureh Kebritchi, Ph.D.

A research problem is the heart of the study. It is a clear, definite statement of the area of concern or investigation and is backed by evidence (Bryman, 2007). It drives the research questions and processes and provides the framework for understanding the research findings. To begin, you will need to know where to look for your research problem and how to evaluate when a research problem for success.

Where to Find a Research Problem

Ideas for research problems tend to come from two sources: real life and the scholarly arena. First, identifying a research problem can be as simple as observing the complications and issues in your local workplace. You may encounter ongoing issues on a daily basis in your workplace or observe your colleagues struggle with major issues or questions in your field. These ongoing obstacles and issues in the workplace can be the catalyst for developing a research problem.

Alternatively, research problems can be identified by reviewing recent literature, reports, or databases in your field. Often the section on “recommendations for future studies” provided at the end of journal articles or doctoral dissertations suggests potential research problems. In addition, major reports and databases in the field may reveal findings or data-based facts that call for additional investigation or suggest potential issues to be addressed. Looking at what theories need to be tested is another opportunity to develop a research problem.

How to Evaluate a Research Problem

Once you find your potential research problem, you will need to evaluate the problem and ensure that it is appropriate for research. A research problem is deemed appropriate when it is supported by the literature and considered significant, timely, novel, specific, and researchable. Stronger research problems are more likely to succeed in publication, presentation, and application.

Supported by the Literature

Your research problem should be relevant to the field and supported by a number of recent peer-reviewed studies in the field. Even if you identify the problem based on the recommendation of one journal article or dissertation, you will still need to conduct a literature search and ensure that other researchers support the problem and the need for conducting research to further address the problem.

Significant

Your research problem should have a positive impact on the field. The impact can be practical, in the form of direct application of the results in the field, or conceptual, where the work advances the field by filling a knowledge gap.

Your research problem should be related to the current needs in the field and well-suited for the present status of the issues in your field. Explore what topics are being covered in current journals in the field. Look at calls from relevant disciplinary organizations. Review your research center agenda and focused topics. For example, the topics of the Research Labs at the Center for Educational and Instructional Technology Research including critical thinking, social media and cultural competency, diversity, and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) in higher education are representative of the current timely topics in the field of education. Identifying a current question in the field and supporting the problem with recent literature can justify the problem's timeliness.

Your research problem should be original and unique. It should seek to address a gap in our knowledge or application. An exhaustive review of the literature can help you identify whether the problem has already been addressed with your particular sample and/or context. Talking to experts in the research area can illuminate a problem. Replication of an existing study warrants a discussion of value elsewhere, but the novelty can be found in determining if an already-resolved problem holds in a new sample and/or context.

Specific and Clear

Your research problem should be specific enough to set the direction of the study, raise research question(s), and determine an appropriate research method and design. Vague research problems may not be useful to specify the direction of the study or develop research questions.

Researchable

Research problems are solved through the scientific method. This means researchability, or feasibility of the problem, is more important than all of the above characteristics. You as the researcher should be able to solve the problem with your abilities and available research methods, designs, research sites, resources, and timeframe. If a research problem retains all of the aforementioned characteristics but it is not researchable, it may not be an appropriate research problem.

References and More Information

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite, clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduces the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Places the topic into a particular context . It defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provides the framework for reporting the results. It indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social and behavioral sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice in a meaningful way.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, understood, and accurately reported],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social and behavioral sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE: A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then be placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary. From this, assume the position of a researcher to explore how a personal experience could be examined as a topic of investigation with outcomes [findings] applicable to others.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where a lack of evidence exists in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people].

NOTE: Authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it. However, simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies [i.e., difference of opinion] and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of a complex research project and realize that you do not have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose a research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be addressed. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. The questions should also relate to each other in some meaningful way . Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community fifty miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community fifty miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Oct 24, 2024 10:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Research Problem

Definition:

Research problem is a specific and well-defined issue or question that a researcher seeks to investigate through research. It is the starting point of any research project, as it sets the direction, scope, and purpose of the study.

Types of Research Problems

Types of Research Problems are as follows:

Descriptive problems

These problems involve describing or documenting a particular phenomenon, event, or situation. For example, a researcher might investigate the demographics of a particular population, such as their age, gender, income, and education.

Exploratory problems

These problems are designed to explore a particular topic or issue in depth, often with the goal of generating new ideas or hypotheses. For example, a researcher might explore the factors that contribute to job satisfaction among employees in a particular industry.

Explanatory Problems

These problems seek to explain why a particular phenomenon or event occurs, and they typically involve testing hypotheses or theories. For example, a researcher might investigate the relationship between exercise and mental health, with the goal of determining whether exercise has a causal effect on mental health.

Predictive Problems

These problems involve making predictions or forecasts about future events or trends. For example, a researcher might investigate the factors that predict future success in a particular field or industry.

Evaluative Problems

These problems involve assessing the effectiveness of a particular intervention, program, or policy. For example, a researcher might evaluate the impact of a new teaching method on student learning outcomes.

How to Define a Research Problem

Defining a research problem involves identifying a specific question or issue that a researcher seeks to address through a research study. Here are the steps to follow when defining a research problem:

- Identify a broad research topic : Start by identifying a broad topic that you are interested in researching. This could be based on your personal interests, observations, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Conduct a literature review : Once you have identified a broad topic, conduct a thorough literature review to identify the current state of knowledge in the field. This will help you identify gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research that can be addressed through your study.

- Refine the research question: Based on the gaps or inconsistencies identified in the literature review, refine your research question to a specific, clear, and well-defined problem statement. Your research question should be feasible, relevant, and important to the field of study.

- Develop a hypothesis: Based on the research question, develop a hypothesis that states the expected relationship between variables.

- Define the scope and limitations: Clearly define the scope and limitations of your research problem. This will help you focus your study and ensure that your research objectives are achievable.

- Get feedback: Get feedback from your advisor or colleagues to ensure that your research problem is clear, feasible, and relevant to the field of study.

Components of a Research Problem

The components of a research problem typically include the following:

- Topic : The general subject or area of interest that the research will explore.

- Research Question : A clear and specific question that the research seeks to answer or investigate.

- Objective : A statement that describes the purpose of the research, what it aims to achieve, and the expected outcomes.

- Hypothesis : An educated guess or prediction about the relationship between variables, which is tested during the research.

- Variables : The factors or elements that are being studied, measured, or manipulated in the research.

- Methodology : The overall approach and methods that will be used to conduct the research.

- Scope and Limitations : A description of the boundaries and parameters of the research, including what will be included and excluded, and any potential constraints or limitations.

- Significance: A statement that explains the potential value or impact of the research, its contribution to the field of study, and how it will add to the existing knowledge.

Research Problem Examples

Following are some Research Problem Examples:

Research Problem Examples in Psychology are as follows:

- Exploring the impact of social media on adolescent mental health.

- Investigating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating anxiety disorders.

- Studying the impact of prenatal stress on child development outcomes.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to addiction and relapse in substance abuse treatment.

- Examining the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships.

Research Problem Examples in Sociology are as follows: