How to Write About Coronavirus in a College Essay

Students can share how they navigated life during the coronavirus pandemic in a full-length essay or an optional supplement.

Writing About COVID-19 in College Essays

Getty Images

Experts say students should be honest and not limit themselves to merely their experiences with the pandemic.

The global impact of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus, means colleges and prospective students alike are in for an admissions cycle like no other. Both face unprecedented challenges and questions as they grapple with their respective futures amid the ongoing fallout of the pandemic.

Colleges must examine applicants without the aid of standardized test scores for many – a factor that prompted many schools to go test-optional for now . Even grades, a significant component of a college application, may be hard to interpret with some high schools adopting pass-fail classes last spring due to the pandemic. Major college admissions factors are suddenly skewed.

"I can't help but think other (admissions) factors are going to matter more," says Ethan Sawyer, founder of the College Essay Guy, a website that offers free and paid essay-writing resources.

College essays and letters of recommendation , Sawyer says, are likely to carry more weight than ever in this admissions cycle. And many essays will likely focus on how the pandemic shaped students' lives throughout an often tumultuous 2020.

But before writing a college essay focused on the coronavirus, students should explore whether it's the best topic for them.

Writing About COVID-19 for a College Application

Much of daily life has been colored by the coronavirus. Virtual learning is the norm at many colleges and high schools, many extracurriculars have vanished and social lives have stalled for students complying with measures to stop the spread of COVID-19.

"For some young people, the pandemic took away what they envisioned as their senior year," says Robert Alexander, dean of admissions, financial aid and enrollment management at the University of Rochester in New York. "Maybe that's a spot on a varsity athletic team or the lead role in the fall play. And it's OK for them to mourn what should have been and what they feel like they lost, but more important is how are they making the most of the opportunities they do have?"

That question, Alexander says, is what colleges want answered if students choose to address COVID-19 in their college essay.

But the question of whether a student should write about the coronavirus is tricky. The answer depends largely on the student.

"In general, I don't think students should write about COVID-19 in their main personal statement for their application," Robin Miller, master college admissions counselor at IvyWise, a college counseling company, wrote in an email.

"Certainly, there may be exceptions to this based on a student's individual experience, but since the personal essay is the main place in the application where the student can really allow their voice to be heard and share insight into who they are as an individual, there are likely many other topics they can choose to write about that are more distinctive and unique than COVID-19," Miller says.

Opinions among admissions experts vary on whether to write about the likely popular topic of the pandemic.

"If your essay communicates something positive, unique, and compelling about you in an interesting and eloquent way, go for it," Carolyn Pippen, principal college admissions counselor at IvyWise, wrote in an email. She adds that students shouldn't be dissuaded from writing about a topic merely because it's common, noting that "topics are bound to repeat, no matter how hard we try to avoid it."

Above all, she urges honesty.

"If your experience within the context of the pandemic has been truly unique, then write about that experience, and the standing out will take care of itself," Pippen says. "If your experience has been generally the same as most other students in your context, then trying to find a unique angle can easily cross the line into exploiting a tragedy, or at least appearing as though you have."

But focusing entirely on the pandemic can limit a student to a single story and narrow who they are in an application, Sawyer says. "There are so many wonderful possibilities for what you can say about yourself outside of your experience within the pandemic."

He notes that passions, strengths, career interests and personal identity are among the multitude of essay topic options available to applicants and encourages them to probe their values to help determine the topic that matters most to them – and write about it.

That doesn't mean the pandemic experience has to be ignored if applicants feel the need to write about it.

Writing About Coronavirus in Main and Supplemental Essays

Students can choose to write a full-length college essay on the coronavirus or summarize their experience in a shorter form.

To help students explain how the pandemic affected them, The Common App has added an optional section to address this topic. Applicants have 250 words to describe their pandemic experience and the personal and academic impact of COVID-19.

"That's not a trick question, and there's no right or wrong answer," Alexander says. Colleges want to know, he adds, how students navigated the pandemic, how they prioritized their time, what responsibilities they took on and what they learned along the way.

If students can distill all of the above information into 250 words, there's likely no need to write about it in a full-length college essay, experts say. And applicants whose lives were not heavily altered by the pandemic may even choose to skip the optional COVID-19 question.

"This space is best used to discuss hardship and/or significant challenges that the student and/or the student's family experienced as a result of COVID-19 and how they have responded to those difficulties," Miller notes. Using the section to acknowledge a lack of impact, she adds, "could be perceived as trite and lacking insight, despite the good intentions of the applicant."

To guard against this lack of awareness, Sawyer encourages students to tap someone they trust to review their writing , whether it's the 250-word Common App response or the full-length essay.

Experts tend to agree that the short-form approach to this as an essay topic works better, but there are exceptions. And if a student does have a coronavirus story that he or she feels must be told, Alexander encourages the writer to be authentic in the essay.

"My advice for an essay about COVID-19 is the same as my advice about an essay for any topic – and that is, don't write what you think we want to read or hear," Alexander says. "Write what really changed you and that story that now is yours and yours alone to tell."

Sawyer urges students to ask themselves, "What's the sentence that only I can write?" He also encourages students to remember that the pandemic is only a chapter of their lives and not the whole book.

Miller, who cautions against writing a full-length essay on the coronavirus, says that if students choose to do so they should have a conversation with their high school counselor about whether that's the right move. And if students choose to proceed with COVID-19 as a topic, she says they need to be clear, detailed and insightful about what they learned and how they adapted along the way.

"Approaching the essay in this manner will provide important balance while demonstrating personal growth and vulnerability," Miller says.

Pippen encourages students to remember that they are in an unprecedented time for college admissions.

"It is important to keep in mind with all of these (admission) factors that no colleges have ever had to consider them this way in the selection process, if at all," Pippen says. "They have had very little time to calibrate their evaluations of different application components within their offices, let alone across institutions. This means that colleges will all be handling the admissions process a little bit differently, and their approaches may even evolve over the course of the admissions cycle."

Searching for a college? Get our complete rankings of Best Colleges.

10 Ways to Discover College Essay Ideas

Tags: students , colleges , college admissions , college applications , college search , Coronavirus

2025 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

What to know about opt.

Anayat Durrani Oct. 24, 2024

We Can Help Struggling College Students

Brian Bridges Oct. 23, 2024

Colleges That Enroll the Most Transfers

Cole Claybourn Oct. 22, 2024

What Not to Wear on Halloween in College

Sarah Wood Oct. 22, 2024

Best Value Out-of-State Public Schools

Decide Whether to Retake the GMAT

Anna Fiorino Oct. 21, 2024

Colleges With Cheap Out-of-State Tuition

Cole Claybourn Oct. 21, 2024

See Average Student Loan Debt Change

Sarah Wood Oct. 21, 2024

How to Study Real Estate Online

Anayat Durrani Oct. 16, 2024

Backing Out of Early Decision

Sarah Wood Oct. 16, 2024

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- About This Blog

- Official PLOS Blog

- EveryONE Blog

- Speaking of Medicine

- PLOS Biologue

- Absolutely Maybe

- DNA Science

- PLOS ECR Community

- All Models Are Wrong

- About PLOS Blogs

Writing a thesis during a pandemic: 4 Lessons

As I enter the last 2 months of my PhD and prepare to hand in my thesis (as you read this I will be editing my final draft) it’s hard not to reflect on the ups and downs of the last 4 years. These last few months have been the hardest; I have been forced to piece together 3 chapters using half-finished data and fill in the gaps as best I can. Thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic I lost a total of 6 months of lab time and during the last 10 months, I have only had partial access to the lab. All of this has been mentally taxing, and I know I’m not the only one who has suffered.

As I reflect on my time as a PhD student I can’t help but evaluate how I think I performed and handled events. As I write up my thesis and do some self-reflection there are a few ideas that keep cropping up, and make me think “I wish I had known that earlier.” Even so I can’t help but think that even if someone had told me these things earlier I wouldn’t have listened; sometimes you have to live through something to learn from it. Either way, to those who are either just starting their PhD or are starting to write their own thesis, here are some tips that writing my thesis has taught me.

95% of things are out of your control

The pandemic put a stop to lots of things; weddings were postponed, visits with family cancelled, and, worst of all, mourning loved ones was put on hold. In the modern age we like to imagine we have control over the world – in reality, we still control very little of what happens to us. During any PhD, unforeseen circumstances will prevent you from doing what you planned; broken equipment, unreliable collaborators, or a shortage of key materials – and that’s on a good day. At the start of my PhD, I assumed I would control what went into my thesis and how good the final product would be. Then comes a global pandemic that halts my ability to gather data (no lab = no experiments). It’s hard to accept but fortune has a habit of doing what it wants. This means it’s up to you to focus on the little you do control. Get upset and angry but then, once that initial reaction passes, figure out what you control and where you can put your energy so it can actually make an impact.

Be the tortoise, not the hare

Writing can be an incredibly dull process, especially in science. You might spend 2 hours reading publications from the last decade only to write two sentences. It can feel like wading through quicksand. The trick is not to put too much pressure on yourself; easier said than done, I know. But when you’re writing any large body of work (the average PhD thesis is 100+ pages) you have to accept that you can’t cram it all in the week before the deadline. Instead, set small goals and set them early. The goal isn’t to write a 100-page masterpiece, the goal is to write 100 words today for 3 months. When we first went into lockdown this was the goal I set for myself. Some days I wrote more, but I always made sure that I wrote 100 words a day. Any progress is progress, no matter how small. Find a goal you can achieve each day and do it.

Guard your time

When the lab eventually reopened (at 50% capacity) writing fell to the bottom of my priority list. It was replaced with lab time, experimental planning, and data analysis. I have realised that this was a huge mistake and I was ignoring my own advice; rather than doing a little every day I did no writing for weeks. As my deadline began to loom closer I realised I needed to re-dedicate time each day to writing. I had to say to push back against my supervisor who wanted me in the lab all day every day that “I’m going to be spending less time in the lab, so I can spend more time writing – sorry.” If you have a thesis to submit writing is as much a priority as lab work. Set some time aside each day or each week, whatever works for you, and spend it dedicated to writing.

Never underestimate the power of editing

Anyone can write words on a page, but telling a good story – that is a challenge. If you want your writing to be more than just words on a page then editing is your best friend. Some people will say the only important part of a thesis is the data. But if the story around the data, how you got it, what it means, why it’s important, is bad then what use is the data? That’s what a thesis does – tells your examiners the story of your PhD. To make that story the best it can be you’re going to need to do a lot of editing, not just for spelling and grammar, but getting the flow and structure right. This has been especially important for me; thanks to the pandemic my data is a bit thin so I need to make sure the story I tell is impressive. As a rule I try to accomplish two full edits of any work I write, depending on time. I also recommend getting friends and family to read your work (you may need to bribe them if they hate science) to spot any obvious mistakes that you will no doubt have missed.

These are just some of the ideas that I have kept in mind when writing up my thesis over the last few months. I hope there is something here you can use when it’s your turn to write up (and hopefully you won’t be doing it during a global pandemic).

Photo by Edwin Hooper on Unsplash under Unsplash License

Steve is currently a member of the EPSRC CDT in Advanced Therapeutics and Nanomedicines at the University of Nottingham. He uses bioelectronics to design new treatments and diagnostic devices. When he's away from the lab he can usually be found lost in the woods or up a mountain. Twitter: @Steve_Gibney

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email for the next time I comment.

Bachelor student, Master student, PhD-student. All education within academia rely on supervisors to be able to step in and lead when students…

In the ever-evolving landscape of academic research, the role of artificial intelligence has undergone a dramatic transformation. Not too long ago, the…

My personal opinion of a professional dilemma Calculations show that only 2–4 % of the global population are flying. Academics from all over…

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The dissertation journey during the COVID-19 pandemic: Crisis or opportunity?

Emmanuel k opoku, li-hsin chen, sam y permadi.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2021 May 15; Revised 2022 Jan 27; Accepted 2022 Feb 17; Issue date 2022 Jun.

Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information website. Elsevier hereby grants permission to make all its COVID-19-related research that is available on the COVID-19 resource centre - including this research content - immediately available in PubMed Central and other publicly funded repositories, such as the WHO COVID database with rights for unrestricted research re-use and analyses in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the COVID-19 resource centre remains active.

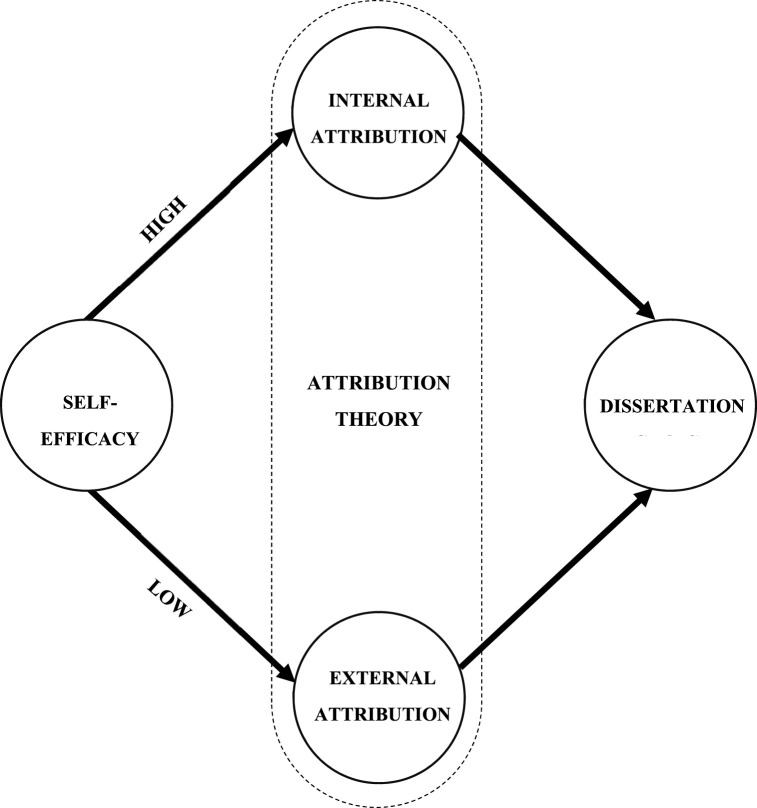

Despite dissertation's significance in enhancing the quality of scholarly outputs in tourism and hospitality fields, insufficient research investigates the challenges and disruptions students experience amidst a public health crisis. This study aims to fill the research gaps and integrate attribution and self-efficacy theories to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic influences students' decision-making and behaviours during the dissertation writing process. Qualitative exploration with 15 graduate students was conducted. The results indicate that adjustment of data collection approaches was the most shared external challenge, while students' religious background and desire for publishing COVID related topics were primary internal motivations.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic, Dissertation writing, Attribution theory, Self-efficacy theory

1. Introduction

Dissertation writing is an essential part of academic life for graduate students ( Yusuf, 2018 ). By writing the dissertation, students can build research skills to analyse new data and generate innovative concepts to inform future scientific studies ( Fadhly et al., 2018 ; Keshavarz & Shekari, 2020 ). Therefore, scholars in higher education are dedicated to guiding students to complete impactful dissertations. Duffy et al. (2018) note that thesis advisors can empower students to explore novel ideas and identify new products or services for the tourism and hospitality industry beyond the traditional contribution of extending the existing research literature. Namely, the intriguing ideas proposed in students’ dissertations will eventually enrich and diversify the literature in the tourism and hospitality academia. Furthermore, the process of identifying impactful ideas will prepare students for a successful career either as a researcher or practitioner.

However, dissertation writing can be a challenging experience for both native and non-native writers. Students are sometimes confused about the characteristics of the dissertation or the expectations from the academics and practitioners ( Bitchener et al., 2010 ). A graduate student has to make numerous decisions during the dissertation writing journey. To successfully guide the students through this complicated writing journey, thesis advisors need to understand the factors influencing students' writing motivation and decision-making process. Previous studies have suggested these influential factors can be broadly classified into external sources (e.g., advisor/supervisor's influence, trends in the field, or publishability of the topic) and internal sources (e.g., researcher's background or researcher interest; Fadhly et al., 2018 ; I'Anson & Smith, 2004 ; Keshavarz & Shekari, 2020 ). Despite this classification, the discussions related to the impacts of macro-environments, such as socio-cultural trends, economic conditions, or ecology and physical environments, on students' dissertation writing are extremely lacking. Since the time background and the world situation when writing a dissertation are also critical factors influencing students' writing goals, more research should be done to broaden students' dissertation writing experiences.

The COVID-19 pandemic has immensely impacted global education, students' learning, and research activities. According to Dwivedi et al. (2020) , the COVID-19 pandemic has affected international higher education leading to the closure of schools to control the spread of the virus. Meanwhile, Alvarado et al. (2021) found that the global health crises have seriously disrupted doctoral students' Dissertations in Practice (DiP). Specifically, students must learn new methodologies and adjust the research settings and sampling techniques because of virtual-only approaches. Some have to find new topics and research questions since the original one cannot be investigated during the quarantine period. However, students may turn this current crisis into an opportunity as they build a shared community and support each other's private and academic lives. Apparently, the crisis can result in a stronger bond of friendship, and this may generate more collaborative research projects in the future.

As mentioned earlier, some studies have tried to identify factors influencing students' dissertation writing journey, albeit lack considerations related to the effects of macro-environments. Given the severe impacts of COVID-19 on the macro-environments of global higher education and the tourism industry, this study aims to fill the research gap and explore how a public health crisis may influence graduate students' dissertation writing, especially in the field of tourism and hospitality. Specifically, this study utilizes attribution and self-efficacy theory as the research framework to examine the internal and external factors that influenced graduate students' dissertation journey amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (see Fig. 1 ). The use of attribution and self-efficacy theory is appropriate in the current study because both explain how people make sense of society, influences of others, their decision-making process and behaviours. Although some may argue these theories are outdated, many scholars have used them to explain students' behaviours and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Xu et al. (2021) found that social capital and learning support positively influence students' self-efficacy, employability and well-being amidst the crisis. Meanwhile, Lassoued et al. (2020) used attribution theory to explore the university professors and their students' learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that both groups attributed the problems to reaching high quality in distance learning to students' weak motivation to understand abstract concepts in the absence of in-person interaction.

The theoretical framework.

Understanding the lived experience of students would enable stakeholders in tourism and hospitality education to deeply comprehend the plight and predicaments of students face and the innovate ways to mitigate those challenges amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, this study utilizes a qualitative approach to explore the impacts of internal and extremal factors on the dissertation writing process. The study was set in the context of an international graduate hospitality and tourism program in Taiwan known for its diverse student body. The research question that guides such qualitative exploration is: How have external and internal factors influenced graduate students’ dissertation writing journey during the COVID-19 pandemic?

This study is timely and critical considering the uncertainties that characterize pandemics which aggravates the already perplexities that associate dissertation writing. It throws light on factors that are susceptible to pandemic tendencies and factors that are resilient to crisis. The findings of this study would provide insights into how crises affect academia and suggest effective ways for higher educational institutions, academicians, and other key stakeholders to forge proactive solutions for future occurrences. Especially, higher education institutions would be well-positioned and informed on areas to train students and faculty members to ameliorate the impacts associated with pandemics.

2. Literature review

2.1. covid-19 and its impacts on educational activities.

Public health crises have ramifications for educational behaviour and choices; this is especially true of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most countries and institutions of higher education are still battling with the consequences suffered from the COVID-19 pandemic. Not surprisingly, there has been a tsunami of studies on the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Dwivedi et al., 2020 ; Manzano-Leon et al., 2021 ; Alam & Parvin, 2021 ). Assessing these studies, we found that although there are substantial extant studies on the negative implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, limited studies have also emphasised the positive side of the pandemic on education. For example, Dwivedi et al. (2020) concluded that the COVID-19 had revealed the necessity of online teaching in higher educational institutions. For they observed that at Loughborough, though face-to-face teaching is practised, one cannot relegate online teaching as some students will be unable to return to campus due to border closures. Thus, faculty members have to convert existing material to the online format. Furthermore, Manzano-Leon et al. (2021) also pointed out that the COVID-19 has allowed students to interact with their peers beyond traditional education. They pinpointed that playful learning strategies such as escape rooms enable students to interact well. Alam and Parvin (2021) also underscored students who studied during the COVID-19 pandemic performed better academically than those before. This finding suggests that online education is supposedly more active than face-to-face mode.

Apart from these positive implications aforementioned, most studies have emphasised the negative impacts of COVID-19 on education. Dwivedi et al. (2020) reviewed how the global higher education sector has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. It caused the closure of schools, national lockdowns and social distancing, and a proliferation of online teaching. COVID-19 forced both teachers and students to work and study remotely from home. According to Dhawan (2020) , the rapid deployment of online learning to protect students, faculty, communities, societies, and nations affected academic life. Online learning seemed like a panacea in the face of COVID-19's severe symptoms; however, the switch to online also brought several challenges for teachers and students. Lall and Singh (2020) noted that disadvantages of online learning include the absence of co-curricular activities and students' lack of association with friends at school. Many studies have also confirmed the pandemic's adverse effects on students' mental health, emotional wellbeing, and academic performance ( Bao, 2020 ; de Oliveira Araújo et al., 2020 ).

Despite the pandemic has caused numerous difficulties for many educational institutions, scholars and educators have risen to the challenges and tried to plan effective strategies to mitigate such stressing circumstances. For example, to respond the needs of a better understanding of students' social-emotional competencies for coping the COVID-19 outbreak, Hadar et al. (2020) utilized the VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, ambiguous) framework to analyse teachers and students' struggles. Each element of VUCA is defined as follows:

Volatility: the speed and magnitude of the crisis;

Uncertainty: the unpredictability of events during the crisis;

Complexity: the confounding events during the crisis;

Ambiguity: the confusing and mixed meanings during the crisis.

This analysis and conceptualization of crises help to explain some of the students’ concerns on mental health, emotional wellbeing, and academic performance ( Bao, 2020 ; de Oliveira Araújo et al., 2020 ).

The pandemic also exacerbated existing challenges facing students and universities across the globe. According to Rose-Redwood et al. (2020) , the COVID-19 endangered the career prospects of both students and scholars. University partnerships with the arts sector, community service, and non-governmental organizations also suffered. The tourism and hospitality (academic) field faced unique challenges in light of COVID-19 without exception. Forms of tourism such as over-tourism and cruise tourism were temporarily unobservable, and most pre-crisis studies and forecast data were no longer relevant ( Bausch et al., 2021 ). Consequently, many empirical and longitudinal studies were halted due to the incomparability of data. Even though many studies have been conducted to explore the impacts of the COVID pandemic on educational activities, none of these studies has addressed how this public health crisis has affected graduate students’ dissertation journey. Therefore, the present research is needed to fill the gaps in the mainstream literature.

2.2. Attribution theory and self-efficacy

The current study employs attribution theory and self-efficacy to understand graduate students' dissertation writing journeys. Attribution theory explains how individuals interpret behavioural outcomes ( Weiner, 2006 ) and has been used in education and crisis management ( Abraham et al., 2020 ; Sanders et al., 2020 ). For example, Chen and Wu (2021) used attribution theory to understand the effects of attributing students' academic achievements to giftedness. They found that attributing students' academic success to giftedness had a positive indirect relationship with their academic achievement through self-regulated learning and negative learning emotions. However, attribution theory has been criticised for its inability to explain a person's behaviour comprehensively. This is well enunciated by Bandura (1986) that attribution theory does not necessarily describe all influential factors related to a person's behaviour. Instead, it provides in-depth accounts of one's self-efficacy. Hence, scholars have advocated the need for integrating self-efficacy into attribution theory ( Hattie et al., 2020 ).

Self-efficacy is closely related to attribution theory. Extant studies have investigated the essence of self-efficacy in education and its role on students' achievements ( Bartimote-Aufflick et al., 2016 ; Hendricks, 2016 ). For instance, in their educational research and implications for music, Hendricks (2016) found that teachers can empower students' ability and achievement through positive self-efficacy beliefs. This is achieved through Bandura's (1986) theoretical four sources of self-efficacy: vicarious experience, verbal/social persuasion, enactive mastery experience, and physiological and affective states. The current study integrates attribution theory and self-efficacy as the research framework to provide intellectual rigour and reasons underlined students' decision-making during their dissertation journey.

2.3. Internal and external factors that influence dissertation writing processes

This study considered both internal and external factors affecting graduate students' dissertation journeys in line with attribution theory. Internal factors are actions or behaviours within an individual's control ( LaBelle & Martin, 2014 ; Weiner, 2006 ). Many studies have evolved and attributed dissertation topic selection to internal considerations. For instance, I'Anson and Smith's (2004) study found that personal interest and student ability were essential for undergraduate students' thesis topic selection. Keshavarz and Shekari (2020) also found that personal interest is the primary motivation for choosing a specific thesis topic. In another study focused on undergraduate students at the English department, Husin and Nurbayani (2017) revealed that students' language proficiency was a dominant internal factor for their dissertation choice decisions.

On the other hand, external factors are forces beyond an individual's control ( LaBelle & Martin, 2014 ). Similar to internal factors, there is an avalanche of studies that have evolved and uncovered external factors that characterize students' dissertation decisions in the pre-COVID period (e.g., de Kleijn et al., 2012 ; Huin; Nurbayani, 2017 ; Keshavarz & Shekari, 2020 ; Pemberton, 2012 ; Shu et al., 2016; Sverdlik et al., 2018 ). For instance, de Kleijn et al. (2012) found that supervisor influence is critical in the student dissertation writing process. They further revealed that an acceptable relationship between supervisor and student leads to a higher and quality outcome; however, a high level of influence could lead to low satisfaction. Meanwhile, Pemberton (2012) delved into the extent teachers influence students in their dissertation process and especially topic selection. This study further underlined that most supervisors assist students to select topics that will sustain their interest and competence level. Unlike previous research, Keshavarz and Shekari (2020) found that research operability or feasibility was a critical external factor that informed students' dissertation decisions. In other words, practicality and usefulness are essential in determining the dissertation choices.

These studies above show how internal and external factors may determine students' dissertation decisions. Despite those studies providing valuable knowledge to broaden our understanding of which factors may play significant role in students' dissertation journeys, most of their focus was on undergraduate students and was conducted before COVID-19. Given that the learning experiences among graduate and undergraduate students as well as before and during the pandemic may differ significantly, there is a need to investigate what specific external and internal factors underline graduate students’ dissertation decisions during the COVID-19. Are those factors different from or similar to previous findings?

3. Methodology

Previous studies have disproportionately employed quantitative approaches to examine students' dissertation topic choice (e.g., Keshavarz & Shekari, 2020 ). Although the quantitative method can aid the researcher to investigate focal phenomena among larger samples and generalize the results, it has also been criticized for the lack of in-depth analysis or does not allow respondents to share their lived experiences. Given the rapid evolution and uncertainty linked with the COVID-19 pandemic, the contextual and social factors may drive individuals to respond to such challenges differently. Therefore, efforts toward analyzing individual experiences during the public health crisis are necessary to tailor individual needs and local educational policy implementation ( Tremblay et al., 2021 ). Accordingly, the current study adopts a qualitative approach grounded in the interpretivism paradigm to explore the factors affecting graduate students’ dissertation research activities and understand the in-depth meaning of writing a dissertation.

3.1. Data collection

Since statistical representation is not the aim of qualitative research, the purposive sampling instead of probability sampling technique was used for this study ( Holloway & Wheeler, 2002 ). Graduate students who were composing their dissertation and could demonstrate a clear understanding on the issues under study are selected as the target research subjects. To gain a rich data, the sample selection in the current study considers background, dissertation writing status, and nationality to ensure a diversified data set ( Ritchie et al., 2014 ). Data was collected from graduate students in Taiwan who were currently writing their dissertations. Taiwan was chosen as the research site because the pandemic initially had a minor impact on Taiwan than on other economically developed countries ( Wang et al., 2020 ). In the first year (2019–2020) of their study, the graduate students could conduct their research projects without any restrictions. Therefore, traditional data collections and research processes, such as face-to-face interview techniques or onsite questionnaire distributions were generally taught and implemented in Taiwanese universities at that time. However, in their second year of the graduate program (2021), the COVID-19 cases surged, and the government identified some domestic infection clusters in Taiwan. Thus, the ministry of education ordered universities to suspend in-person instruction and move to online classes from home as part of a national level 3 COVID-19 alert. Many graduate students have to modify their data collection plan and learn different software to overcome the challenges of new and stricter rules. As they have experienced the sudden and unexpected change caused by the COVID-19 in their dissertation writing journey, Taiwanese graduate students are deemed as suitable research participants in this research.

Following Keshavarz and Shekari (2020) , interview questions were extracted from the literature review and developed into a semi-structured guide. Semi-structured interview was employed allowing for probing and clarifying explanations. This also allowed both the interviewer and the interviewee to become co-researchers (Ritchie et al., 2005). The questions asked about internal, and external factors influencing dissertation writing (including topic selection and methodology) during COVID-19. Specifically, students were asked how they chose their dissertation topic, how they felt COVID-19 had impacted their dissertation, and what significant events influenced their academic choices during the pandemic. Before each interview, the purpose of the study was explained and respondents provided informed consent. All the interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed.

Interviews, lasting about 50–60 min, were conducted with 15 graduate students as data saturation was achieved after analysing 15 interviews. The saturation was confirmed by the repetition of statements like, “personal interest motivated me”, “my supervisor guided me to select a topic”, and “I changed my data collection procedure to online”.

3.2. Data analysis and trustworthiness

Before the formal interview, two educational experts who are familiar with qualitative research were solicited to validate the wording, semantics, and meanings of the interview questions. Then, a pilot test was conducted with three graduate students to check the clarity of the expression for every interview question and revise potentially confusing phrasing. Validity and trustworthiness were also achieved through the use of asking follow-up questions. The transcripts of formal interviews were analysed using Atlas.ti 9. Qualitative themes were developed following open, selective, and axial coding procedures ( Corbin & Strauss, 1990 ). Finally, the relationships among themes and codes were identified, facilitating the research findings and discussions.

In order to prevent biases from affecting the findings of the study, series of procedures were undertaken following previous qualitative research. First, multiple quotations from respondents underlined the research findings which meant the respondents' true perspectives and expressions were represented. Moreover, the analyses were done independently and there was peer checking among the authors. There was also member checking where themes found were redirected to respondents for verification. In addition, external validation of the themes was done by asking other graduate students who share similar characteristics for comparability assessment to make the findings transferable.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. profile of respondents.

Respondents were purposively drawn from diverse backgrounds (including nationality, gender, and programs) to enrich the research findings. The sample includes graduate students who began dissertation writing in Taiwan during the COVID-19 pandemic period. The majority of the respondents are female and from South East Asia. Table 1 provides background information of these interviewees.

Background information of study respondents.

4.2. Internal factors

As Table 2 depicts, the themes ascertained from the data analysis were categorised according to internal and external factors which underpin the attribution theory ( Weiner, 2006 ). In consonance with previous studies, graduate students’ dissertation writing during the pandemic was influenced by internal factors (i.e., personal interest and religious background) and external considerations (i.e., career aspirations, society improvement, language issues, supervisor influence, COVID-19 publishable topics, data collection challenges). The analyses of each factor are presented below.

Major themes and codes emerging from the data.

The most salient internal factors affecting dissertation topic selection were (1) personal interest and (2) religious background. For personal interest, respondent 1 expressed:

The first thing is that [it] comes from my interest. I'm currently working on solo female traveller [s], which is the market I want to study. So, the priority comes from my personal preference and to learn about this market no matter the external situation. I also think that this is due to how I was brought up. My parent nurtured me that way, and I love to do things independently, especially when travelling.

This finding is in line with previous studies such as Keshavarz and Shekari (2020) ; I’Anson and Smith (2004) , who emphasised the relevance of personal interest in students' dissertation decision-making. Informed by the self-efficacy and attribution theories, we found that students who attribute their decision-making on dissertation writing to internal factors (i.e., personal interest) have relatively high self-efficacy levels. As argued by Bandura (1977) , efficacy expectation is “the conviction that one can successfully execute the behaviour required to produce the outcomes” (p. 193). Namely, self-efficacy is determined by an individual's capability and ability to execute decisions independently, devoid of any external considerations. Despite the uncertainties and challenging circumstances amidst COVID-19, students who believe their ability and research skills usually adhere to their original dissertation topics and directions.

Religious consideration is another conspicuous factor informing graduate students' dissertation journey during the COVID-19 pandemic. As respondent 7 mentioned:

Islam has become my way of life. I am a Muslim. It is my daily life, so I like to research this. I was born into this faith, and I am inclined to explore Halal food. I feel committed to contributing my research to my faith no matter outside circumstances. Maybe if I combine it with academic (research), it will be easier to understand and easier to do.

Although not much has been seen regarding religious considerations in students' dissertation topic selection in previous studies, this research reveals religious background as a significant internal factor. From a sociology perspective, religious orientation and affiliation could affect individual behaviour ( Costen et al., 2013 ; Lee & Robbins, 1998 ), and academic decision-making is not an exception. Religious backgrounds are inherent in the socialisation process and could affect how a person behaves or how they make a particular decision. This premise is further accentuated by Costen et al. (2013) , who argued that social connectedness affects college students' ability to adjust to new environments and situations. Social connectedness guides feelings, thoughts, and behaviour in many human endeavours ( Lee & Robbins, 1998 ). Social connectedness and upbringing underpin peoples' personality traits and behavioural patterns. Therefore, this study has extended existing literature on factors that affect graduate students' decision-making on dissertation writing from a religious perspective, which is traceable to an individual's socialisation process. In other words, during crises, most students are inclined to make decisions on their dissertation writing which are informed by their social upbringing (socialisation).

4.3. External factors

As Table 2 indicates, abundant external factors inform graduate students’ decision-making on their dissertation writing process. Except for career aspirations, language concerns, and supervisor influences that previous studies have recognized ( Chu, 2015 ; Jensen, 2013 ; Keshavarz & Shekari, 2020 ; Lee & Deale, 2016 ; Tuomaala et al., 2014 ), some novel factors were identified from the data, such as “COVID-19 publishable topic” and “online data collection restrictions”.

Unlike extant studies that have bemoaned the negative impacts of the COVID on education ( Qiu et al., 2020 ; Sato et al., 2021 ), the current study revealed that graduate students were eager to research on topics that were related to COVID-19 to reflect the changes of the tourism industry and trends.

Initially, overtourism [was] a problem in my country, and I want to write a dissertation about it. However, there is no tourism at my research site because of the COVID-19 pandemic. So, I had to change my topic to resilience because resilience is about overcoming a crisis. I had to discuss with my supervisor, and she suggested the way forward that I revise my topic to make it relevant and publishable due to the COVID-19 pandemic (respondent 8).

This response shows the unavoidable impacts of the COVID-19 on the research community. As Bausch et al. (2021) pointed out, tourism and hospitality scholars have to change their research directions because some forms of tourism such as overtourism and cruise tourism were temporarily unobservable amidst the pandemic. Thus, many pre-pandemic studies and forecast data were no longer relevant. However, the COVID-19 pandemic can bring some positive changes. Nowadays, the industry and academics shift their focus from pro-tourism to responsible tourism and conduct more research related to resilience. As Ting et al. (2021) suggested, “moving forward from the pandemic crisis, one of the leading roles of tourism scholars henceforth is to facilitate high-quality education and training to prepare future leaders and responsible tourism practitioners to contribute to responsible travel and tourism experiences.” (p. 6).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has significant ramifications upon the research methods in hospitality and tourism. As respondent 1 denoted,

Because of [the] COVID-19 pandemic, there were certain limitations like I cannot analyse interviewee's body language due to social distancing … some interruptions when we conduct online interviews due to unstable internet connectivity, which would ultimately affect the flow of the conversation.

The adjustments of research methods also bring frustrations and anxiety to students. For instance, respondent 3 expressed: “I became anxious that I won't be able to collect data because of social distancing, which was implemented in Taiwan.” The volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) feelings caused by the COVID-19 pandemic significantly influences students' mood, thinking and behaviour ( Hadar et al., 2020 ).

Apparently, during crises, graduate students' decision-making on their dissertation writing was precipitated by external considerations beyond their control. Based on self-efficacy and attribution theory, the fear that characterises crises affects students' self-efficacy level and eagerness to resort to external entities (e.g., supervisor influences or difficulties in collecting data) to assuage their predicament. In other words, some students may have a low self-efficacy level during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was triggered by the negative impacts of the crisis. Furthermore, scholars may need to notice that COVID-19 is likely to affect conclusions drawn on studies undertaken during this period due to over-reliance on online data collection.

5. Conclusions and implications

Although numerous studies have been conducted to understand the influences of the COVID-19 crisis on educational activities, none of them focuses on the graduate student's dissertation writing journey. Given the significant contributions dissertations may make to advancing tourism and hospitality knowledge, this study aims to fill the gap and uses attribution and self-efficacy theories to explore how internal and external factors influenced graduate students' decision-making for dissertations amidst the crisis. Drawing on qualitative approaches with graduate students who began writing their dissertation during the COVID-19 period, the study provides insights into students' learning experiences and informs stakeholders in hospitality and tourism education to make better policies.

There are several findings worthy of discussion. Firstly, graduate students' sociological background (i.e., personal interest and religious background), which is inherent in an individual's socialisation processes, inform their decision-making in the dissertation processes during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is in line with the self-efficacy theory, which argues that an individual has the conviction that they have the necessary innate abilities to execute an outcome ( Bandura, 1977 ). Namely, respondents with high self-efficacy levels attributed their decisions to internal factors. Unlike previous studies' findings that personal interest was a factor that underpinned graduate students' decision-making ( I'Anson & Smith, 2004 ; Keshavarz & Shekari, 2020 ), it is observed that religious background is an additional factor that was evident and conspicuous during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Secondly, the complexity and uncertainty that characterised the COVID-19 pandemic made emotion a dominant factor that affected graduate students’ dissertation journey and indirectly triggered other external factors that provoked behavioural adjustments among students. The trepidation and anxiety that COVID-19 has caused significantly affects the self-efficacy level of students and predisposes them to external considerations, such as the will of the supervisor or the difficulties in data collection, in their dissertation journey. This study paralleled previous research and revealed that respondents with low self-efficacy were influenced by external considerations more than individuals with high self-efficacy ( Bandura, 1977 ). However, this study highlights how a public health crisis accelerates students who have low self-efficacy to attribute their unsatisfactory academic life to the external environment, leading to depression and negative impacts on ideology ( Abood et al., 2020 ).

Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically influenced the direction of research and body of knowledge in tourism and hospitality. This is seen in the light of the influx of COVID-19 related research topics adapted by graduate students. Furthermore, over-reliance on online data collection approaches were observed in this research. Although online surveys and interviews have many advantages, such as low cost and no geographic restrictions, the results drawn from this approach frequently suffer from biased data and issues with reliability and validity. For example, Moss (2020) revealed that survey respondents from Amazon MTurk are mostly financially disadvantaged, significantly younger than the U.S. population, and predominantly female. As more and more students collect data from online survey platforms such as Amazon MTurk, dissertation advisors may need to question the representativeness of the study respondents in their students’ dissertation and the conclusions they make based on this population.

5.1. Theoretical implications and future study suggestions

This paper has extended the attribution and self-efficacy theories by revealing that a public health crisis moderates attributive factors that underpinned the decision-making of individuals. The integration of self-efficacy theory and attributive theory has proven to better unravel the behaviour of graduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic than solely utilizing one of them. The application and extension of the self-efficacy and attribution theories are rarely observed in the context of hospitality and tourism education, and thus, this study creates the foundation for future scholars to understand students’ attitudes and behaviour in our field.

The findings highlight some factors triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and have not been identified previously. For example, the religious background was a significant driver to selecting a particular research topic. This research also shows a shift in research direction to hot and publishable issues related to COVID-19. The utility of the dissertation becomes a significant consideration among graduate students. Additionally, emotion is recognized as another critical factor affecting the dissertation writing journey. The current study informs academia and the research community on the extent to which the COVID-19 would influence idea generation and the direction of research in the foreseeable future, as extant studies have overlooked this vital connection. Future studies should consider those factors when investigating relevant behaviours and experiences.

The time that the current study was done is likely to affect the findings. Therefore, it is recommended that future research explore graduate students’ dissertation journey in the post-COVID-19 era to ascertain whether there will be similarities or differences. This would help to give a comprehensive picture of the impacts of the COVID-19 on education. Moreover, the findings of this study cannot be generalised as it was undertaken at a particular Taiwanese institution. We recommend that quantitative research with larger samples could be conducted to facilitate the generalisation of the findings. Finally, it is suggested that a meta-analysis or systematic literature review on articles written on the COVID-19 pandemic and education could be done to further identify more influential factors related to the public health crisis and educational activities.

5.2. Practical implications for hospitality and tourism education

The findings revealed that negative emotion might trigger students' attribution to external factors that affected the dissertation journey. Thus, relevant stakeholders should develop strategies and innovate ways to ease the fears and anxieties of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study calls for immediate actions to prevent spillover effects on upcoming students. Faculty members, staff, and teachers should be trained on soft skills such as empathy, flexibility, and conflict solutions required by the hospitality and tourism industry.

Moreover, the thesis supervisors should notice students' over-reliance on online data collection due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As it may possibly affect the quality and findings of their students' dissertations, there should be sound and logical justification for this decision. Collecting data online should be backed by the appropriateness of the method and the research problem under study instead of the convenience of obtaining such data. There is an urgent need for students to be guided for innovative data collection methods. The school can turn the COVID-19 crisis into an opportunity to improve the online teaching materials and equipment. The research programs may consider including more teaching hours on online research design or data collection procedures to bring positive discussions on the strengths of such approaches.

Credit author statement

Emmanuel Kwame Opoku: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. Li-Hsin Chen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Review, Editing, Response to reviewers. Sam Yuan Permadi: Investigation, Visualization, Project administration.

- Abood M.H., Alharbi B.H., Mhaidat F., Gazo A.M. The relationship between personality traits, academic self-efficacy and academic adaptation among university students in Jordan. International Journal of Higher Education. 2020;9(3):120–128. [ Google Scholar ]

- Abraham V., Bremser K., Carreno M., Crowley-Cyr L., Moreno M. Exploring the consequences of COVID-19 on tourist behaviors: Perceived travel risk, animosity and intentions to travel. Tourism Review. 2020;74(2):701–717. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alam G.M., Parvin M. Can online higher education be an active agent for change? Comparison of academic success and job-readiness before and during COVID-19. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021;172 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121034. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alvarado C., Garcia L., Gilliam N., Minckler S., Samay C. Pandemic pivots: The impact of a global health crisis on the dissertation in practice. Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice. 2021;6(2):5–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2) doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. 191-125. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A. Prentice Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bao W. COVID-19 and online teaching in higher education: A case study of Peking university. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020;2(2):113–115. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.191. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartimote-Aufflick K., Bridgeman A., Walker R., Sharma M., Smith L. The study, evaluation, and improvement of university student self-efficacy. Studies in Higher Education. 2016;41(11):1918–1942. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bausch T., Gartner W.C., Ortanderl F. How to avoid a COVID-19 research paper tsunami? A tourism system approach. Journal of Travel Research. 2021;60(3):467–485. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bitchener J., Basturkmen H., East M. The focus of supervisor written feedback to thesis/dissertation students. International Journal of English Studies. 2010;10(2):79–97. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen M., Wu X. Attributing academic success to giftedness and its impact on academic achievement: The mediating role of self-regulated learning and negative learning emotions. School Psychology International. 2021;42(2):170–186. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chu H. Research methods in library and information science: A content analysis. Library & Information Science Research. 2015;37(1):36–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbin J.M., Strauss A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology. 1990;13(1):3–21. [ Google Scholar ]

- Costen W.M., Waller S.N., Wozencroft A.J. Mitigating race: Understanding the role of social connectedness and sense of belonging in African–American student retention in hospitality programs. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sports and Tourism Education. 2013;12(1):15–24. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dhawan S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 2020;49(1):5–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duffy L.N., Pinckney IV H.P., Powell G.M., Bixler R.D., McGuire F.A. Great theses and dissertation start with an intriguing idea. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sports and Tourism Education. 2018;22:82–87. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwivedi Y.K., Hughes D.L., Coombs C., Constantiou I., Duan Y., Edwards J.S., Gupta B., Lal B., Misra S., Prashant P. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on information management research and practice: Transforming education, work and life. International Journal of Information Management. 2020;55 [ Google Scholar ]

- Fadhly F.Z., Emzir E., Lustyantie N. Exploring cognitive process of research topic selection in academic writing. Journal of English Education. 2018;7(1):157–166. English Review. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hadar L.L., Ergas O., Alpert B., Ariav T. Rethinking teacher education in a VUCA world: Student teachers' social-emotional competencies during the Covid-19 crisis. European Journal of Teacher Education. 2020;43(4):573–586. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hattie J., Hodis F.A., Kang S.H. Theories of motivation: Integration and ways forward. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2020;61 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hendricks K.S. The sources of self-efficacy: Educational research and implications for music. UPDATE: Applications of Research in Music Education. 2016;35(1):32–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Holloway I., Wheeler S. Wiley-Blackwell; London, UK: 2002. Qualitative research in nursing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Husin M.S., Nurbayani E. The ability of Indonesian EFL learners in writing academic papers. Dinamika Ilmu. 2017;17(2):237–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- I'Anson R.A., Smith K.A. Undergraduate Research Projects and Dissertations: Issues of topic selection, access and data collection amongst tourism management students. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sports and Tourism Education. 2004;3(1):19–32. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jensen P.H. Choosing your PhD topic (and why it is important) The Australian Economic Review. 2013;46(4):499–507. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeynes W.H. Religiosity, religious schools, and their relationship with the achievement gap: A research synthesis and meta-analysis. The Journal of Negro Education. 2010:263–279. [ Google Scholar ]

- Keshavarz H., Shekari M.R. Factors affecting topic selection for theses and dissertations in library and information science: A national scale study. Library & Information Science Research. 2020;42(4) [ Google Scholar ]

- de Kleijn R.A., Mainhard M.T., Meijer P.C., Pilot A., Brekelmans M. Master's thesis supervision: Relations between perceptions of the supervisor–student relationship, final grade, perceived supervisor contribution to learning and student satisfaction. Studies in Higher Education. 2012;37(8):925–939. [ Google Scholar ]

- LaBelle S., Martin M.M. Attribution theory in the college classroom: Examining the relationship of student attributions and instructional dissent. Communication Research Reports. 2014;31(1):110–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lall S., Singh N. Covid-19: Unmasking the new face of education. International Journal of Research in Pharmacy and Science. 2020;11(1):48–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lassoued Z., Alhendawi M., Bashitialshaaer R. An exploratory study of the obstacles for achieving quality in distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences. 2020;10(9):232. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee S.H., Deale C.S. A matter of degrees: Exploring dimensions in the Ph.D. student–advisor relationship in hospitality and tourism education. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism. 2016;16(4):316–330. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee R.M., Robbins S.B. The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45(3):338–345. [ Google Scholar ]

- Manzano-León A., Aguilar-Parra J.M., Rodríguez-Ferrer J.M., Trigueros R., Collado-Soler R., Méndez-Aguado C.…Molina-Alonso L. Online escape room during COVID-19: A qualitative study of social education degree students' experiences. Education Sciences. 2021;11(8):426. [ Google Scholar ]

- Moss A. 2020. Demographics of people on Amazon mechanical Turk. https://www.cloudresearch.com/resources/blog/who-uses-amazon-mturk-2020-demographics/ Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- de Oliveira Araújo F.J., de Lima L.S.A., Cidade P.I.M., Nobre C.B., Neto M.L.R. Impact of Sars-Cov-2 and its reverberation in global higher education and mental health. Psychiatry Research. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112977. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pemberton C.L.A. A “How-to” guide for the education thesis/dissertation process. Kappa Delta Pi Record. 2012;48(2):82–86. [ Google Scholar ]

- Qiu H., Li Q., Li C. How technology facilitates tourism education in COVID-19: Case study of nankai university. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sports and Tourism Education. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2020.100288. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ritchie J., Lewis J., Nicholls C.M., Ormston R. 4th ed. Sage; London, UK: 2014. Qualitative research practice. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rose-Redwood R., Kitchin R., Apostolopoulou E., Rickards L., Blackman T., Crampton J., Rossi U., Buckley M. Geographies of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues in Human Geography. 2020;10(2):97–106. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sanders K., Nguyen P.T., Bouckenooghe D., Rafferty A., Schwarz G. Unraveling the what and how of organizational communication to employees during COVID-19 pandemic: Adopting an attributional lens. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2020;56(3):289–293. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sato S., Kang T.A., Daigo E., Matsuoka H., Harada M. Graduate employability and higher education's contributions to human resource development in sport business before and after COVID-19. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sports and Tourism Education. 2021;28 [ Google Scholar ]

- Sverdlik A., Hall N.C., McAlpine L., Hubbard K. The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students' completion, achievement, and well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies. 2018;13(1):361–388. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ting H., Morrison A., Leong Q.L. Editorial - responsibility, responsible tourism and our responses. Journal of Responsible Tourism Management. 2021;1(2):1–9. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tremblay S., Castiglione S., Audet L.-A., Desmarais M., Horace M., Peláez S. Conducting qualitative research to respond to COVID-19 challenges: Reflections for the present and beyond. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2021 doi: 10.1177/16094069211009679. Advance online publication. [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tuomaala O., Järvelin K., Vakkari P. Evolution of library and information science, 1965–2005: Content analysis of journal articles. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 2014;65(7):1446–1462. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang C.J., Ng C.Y., Brook R.H. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1341–1342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weiner B. Psychology Press; New York: 2006. Social motivation, justice, and the moral emotions: An attributional approach. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu P., Peng M.Y.P., Anser M.K. Effective learning support towards sustainable student learning and well-being influenced by global pandemic of COVID-19: A comparison between mainland China and Taiwanese students. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.561289. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yusuf A. Factors influencing post graduate students' choice of research topic in education at Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi-Nigeria. Sumerianz Journal of Education, Linguistics and Literature. 2018;1(2):35–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (559.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

The Essex website uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are consenting to their use. Please visit our cookie policy to find out which cookies we use and why. View cookie policy.

Thesis Submission Guidance: COVID-19 Impact Statement

In response to the impact of the global pandemic, we’re giving you the option to include a statement at the start of your thesis which outlines the effects that COVID-19 may have had on the research that you have undertaken towards your doctoral degree.

The inclusion of a statement is to facilitate the reader’s awareness, both now and in the future, that the pandemic may have had an effect on the scope, direction and presentation of the research.

The academic standards and quality threshold for the award remains unchanged. Where statements are included, you should be reassured that this is not evidencing a lack of original research or intellectual rigour.

If you decide to include one such statement, it should appear on the first page of the thesis, after the cover page, and be titled ‘Impact of COVID-19’. The statement should not exceed 1000 words and will not count towards the total thesis word count.

Examples of potential areas for consideration and comment when developing your impact statement are below. However, you should discuss the content of the statement with your supervisor before submission:

- Details on how disruption caused by COVID-19 has impacted the research (for example, an inability to conduct face to face research, an inability to collect/analyse data as a result of travel constraints, or restricted access to labs or other working spaces).

- A description of how the planned work would have fitted within the thesis narrative (e.g., through method development, expansion of analytical skills or advancement of hypotheses).

- A summary of any decisions / actions taken to mitigate for any work or data collection/analyses that were prevented by COVID-19.

- Highlighting new research questions and developments, emphasising the work that has been undertaken in pivoting or adjusting the project.

You are reminded of the public nature of the published thesis and the longevity of any such included statements about the impact of the pandemic. You are advised to take a cautious approach as to the insertion of any personal information in these statements.

- For enquiries contact your Student Services Hub

- University of Essex

- Wivenhoe Park

- Colchester CO4 3SQ

- Accessibility

- Privacy and Cookie Policy

Mitigating the Challenges of Thesis Writing During the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Autoethnographic Reflection of Two Doctoral Students’ Perezhivanie

- First Online: 02 January 2023

Cite this chapter

- Jennifer Cutri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5328-5332 4 &

- Ricky W. K. Lau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2340-2366 5

1090 Accesses

4 Citations

3 Altmetric

Undertaking a doctoral degree is a challenging but worthwhile endeavour where PhD students invest years of academic, physical, and emotional energy contributing to their specialist field. The emotional toll upon doctoral students’ wellbeing has been highlighted in recent years. More recently, another issue has impacted PhD students—the COVID-19 pandemic. While emerging research has highlighted doctoral students’ struggles and coping mechanisms, we offer our experience as two PhD students navigating our ways through the unknown terrain of doctoral study as a couple during a pandemic. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, we were forced to retreat from our allocated offices at the university and write together within the same vicinity at home during the sudden lockdown. During this time, we found that even though writing a thesis was stressful and our future was uncertain due to the pandemic, we found comfort and solace in each other. Writing together, in isolation, has brought us together. As we are in different disciplines—Medicine and Education, we also learnt how to approach our theses from different perspectives and became more resilient in our development as researchers. We discuss how our research backgrounds influenced the way we experienced academia and what we learnt from each other. We employ Vygotsky’s term of perezhivanie to capture our emotional journey and academic development together to represent the unique environmental conditions experienced.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

I Can’t Complain

Anxiety, Desire, Doubt, and Joy: The Dualities of a Latin American Emerging Researcher during Academic Writing Processes

“The Powerful Play Goes on and You May Contribute a Verse…”: Reflecting on the Critical Pedagogy and Mentorship of Dr. Bruce A. Arrigo

Blunden, A. (2016). Translating perezhivanie into English. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 23 (4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2016.1186193

Article Google Scholar

Blunden, A. (2021). Chapter 25: The coronavirus pandemic is a world perezhivanie. In A. Blunden (Ed.), Hegel, Marx and Vygotsky (pp. 402–406). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004470972_027

Boaz, J. (2021, October 3). Melbourne passes Buenos Aires’ world record for time spent in COVID-19 lockdown . ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-03/melbourne-longest-lockdown/100510710

Börgeson, E., Sotak, M., Kraft, J., Bagunu, G., Biörserud, C., & Lange, S. (2021). Challenges in PhD education due to COVID-19 - disrupted supervision or business as usual: A cross-sectional survey of Swedish biomedical sciences graduate students. BMC Medical Education, 21 , Article 294. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02727-3

Bozhovich, L. I. (2009). The social situation of child development. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 47 (4), 59–86. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405470403

Byrom, N. (2020). COVID-19 and the research community: The challenges of lockdown for early-career researchers. eLife, 9 , Article e59634. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.59634

Cahusac de Caux, B. (2022a). The effects of the pandemic on the research output and strategies of early career researchers and doctoral candidates. In B. Cahusac de Caux, L. Pretorius, & L. Macaulay (Eds.), Research and teaching in a pandemic world: The challenges of establishing academic identities during times of crisis . Springer.

Google Scholar

Cahusac de Caux, B. (2022b). Introduction to the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on academia. In B. Cahusac de Caux, L. Pretorius, & L. Macaulay (Eds.), Research and teaching in a pandemic world: The challenges of establishing academic identities during times of crisis . Springer.

Cross, R. (2012). Creative in finding creativity in the curriculum: The CLIC second language classroom. Australian Education Research, 39 (4), 431–445. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ984464

Dang, T. K. A. (2013). Identity in activity: Examining teacher professional identity formation in the paired-placement of student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 30 , 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.006

Davis, S. (2021). Perezhivanie, art, and creative traversal: A method of marking and moving through COVID and grief. Qualitative Inquiry, 27 (7), 767–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420960158

Davis, S., & Phillips, L. G. (2020). Teaching during COVID 19 times – The experiences of drama and performing arts teachers and the human dimensions of learning. NJ, 44 (2), 66–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/14452294.2021.1943838

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 36 (4), 273–290. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23032294

Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014a). Funds of identity: A new concept based on the funds of knowledge approach. Culture & Psychology, 20 (1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13515934

Esteban-Guitart, M., & Moll, L. C. (2014b). Lived experience, funds of identity and education. Culture & Psychology, 20 (1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X13515940

Etmanski, B. (2019). The prospective shift away from academic career aspirations. Higher Education, 77 , 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0278-6

Evans, T., Bira, L., Gastelum, J., Weiss, L., & Vanderford, N. (2018). Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nature Biotechnology, 36 (3), 282–284. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.4089

Ferholt, B. (2010). A synthetic-analytic method for the study of perezhivanie: Vygotsky’s literary analysis applied to playworlds. In M. C. Connery, V. P. John-Steiner, & A. Marjanovic-Shane (Eds.), Vygotsky and creativity: A cultural-historical approach to play, meaning making, and the arts (pp. 163–179). Peter Lang.

Fleer, M., González Rey, F., & Veresov, N. (2017). Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Setting the stage. In M. Fleer, F. González Rey, & N. Veresov (Eds.), Perezhivanie, emotions and subjectivity: Advancing Vygotsky’s legacy (pp. 1–15). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4534-9_1

Freya, A., & Cutri, J. (2022). “Memeing it up!”: Doctoral students’ reflections of collegiate virtual writing spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic. In B. Cahusac de Caux, L. Pretorius, & L. Macaulay (Eds.), Research and teaching in a pandemic world: The challenges of establishing academic identities during times of crisis . Springer.

Ghaffarzadegan, N., Hawley, J., & Desai, A. (2014). Research workforce diversity: The case of balancing national versus international postdocs in US biomedical research. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 31 (2), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2190