A Summary and Analysis of Shakespeare’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy from Hamlet

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

‘To be, or not to be, that is the question’: perhaps one of the most famous lines in all of English literature, but arguably also one of the most mysterious – and one of the most misread. Hamlet’s soliloquy from William Shakespeare’s play is rightly celebrated for being a meditation on the nature of life and death, but some interpretations of the soliloquy serve to reduce the lines to a more simplistic meaning. So what does ‘To be or not to be’ really mean?

To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Virtually everyone knows the line, ‘To be, or not to be: that is the question’. Whether we hear Laurence Olivier reciting them, or erroneously picture some other great Shakespearean actor pronouncing these words while holding a skull (which actually belongs in the later gravedigger scene), ‘To be or not to be’ is one of the most famous six-line phrases from all of English literature.

But interestingly, in the first printing of Hamlet , the lines were quite different (see the image from the Quarto, below right): ‘To be, or not to be: that is the question’ was instead ‘To be, or not to be, I there’s the point’ (this version may have been actors or audience-members misremembering the lines from the play and trying to reconstruct them from memory).

Yet the precise meaning of these words, and the lines that follow, is often analysed in a way that not only reduces the ambiguity of the lines to a simple and straightforward narrative (Hamlet is pondering whether to kill himself or not) but also risks losing sight of the broader context in which they appear, namely the play Hamlet viewed as a whole.

For if there is one thing that marks Hamlet (and the character, Hamlet), it is his supposed vacillation, his indecision, his delaying: and his dilatoriness centres on his failure to take revenge on his uncle, Claudius, for the murder of his father, Old Hamlet.

What makes ‘To be or not to be’ such a cryptic utterance is that the lines telegraph, and even actively elide, the full thought which Hamlet is mulling over. Should ‘To be or not to be’ be silently completed by us as ‘To be alive or not to be alive’ (the ‘suicide’ interpretation), or as ‘To be an avenger or not to be an avenger’ (bringing in the revenge plot of the play)?

The problem is that the lines which follow, far from being specifically about the pros and cons of killing oneself, can actually be used to support either interpretation.

To ‘suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, / Or to take arms against a sea of troubles / And by opposing end them’ sounds like somebody wondering whether to carry on living or to end it all, but these lines might just as easily refer to Hamlet’s dilemma over whether to accept the challenge mounted by the Ghost (avenge his murdered father) or to stand by and passively let things play out as ‘fortune’ decrees.

The lines that follow:

To die—to sleep, No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to

Seem to be more specifically focused on the suicide question, but even here there is some ambiguity. Given that the Ghost of his dead father is firmly on young Hamlet’s mind, he is also meditating here on what happens when we die (not just on what might happen when he dies).

The Ghost appears to call into question that ‘to die’ is ‘to sleep’, since Old Hamlet has not been allowed to rest; he is a ‘traveller’ who has returned from that ‘undiscovered country’ beyond the grave.

Hamlet’s delaying tactics are themselves often misinterpreted. Is it fair to say that Hamlet delays? Yes. Is it fair to say that he delays because he is indecisive? That’s less certain. He certainly gives us that impression, and torments himself for being not ‘man’ enough to avenge his father.

But Hamlet’s ‘failure’ to act immediately is actually downright sensible, since he wants to be sure that the Ghost which he spoke to, which assumed the form of his father, actually was his father and spoke truth to him, rather than being some mischievous demon sent to goad him to murder an innocent man. This is why he puts on the ‘play within a play’ (actually called The Murder of Gonzago , but which Hamlet wittily renames The Mousetrap ): to try to collect evidence of Claudius’ guilt.

As this is a soliloquy from a Shakespeare play, ‘To be or not to be’ is in iambic pentameter – specifically, unrhymed iambic pentameter, or blank verse . But there are a number of variations. Should we stress ‘that’ or ‘is’ in ‘that is the question’? Although ‘ that is the question’ may be more common an interpretation, ‘that is the question’ is viable too.

For our money, the best interpretation of Shakespeare’s lines was by the great actor Paul Scofield; you can hear him reciting ‘To be or not to be’ here . For more about the play, see our analysis of Hamlet and our study of the character of Hamlet . You might also find our analysis of another of Hamlet’s soliloquies, ‘ O, that this too too solid flesh would melt ’, of interest.

About Hamlet

But despite – or, perhaps, because of – this emotional intensity and complexity, actors down the ages have been keen to put their own stamp on the role, including David Garrick (who had a special wig that made Hamlet’s hair stand on end when the ghost of his father appeared), Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Mel Gibson, Sarah Bernhardt (one of many women to portray the Prince of Denmark), Ethan Hawke, Keanu Reeves, Kenneth Branagh, Maxine Peake, and even John Wilkes Booth, the man who assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

13 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of Shakespeare’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy from Hamlet”

- Pingback: Five Fascinating Facts about Hamlet | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Seven of the Best Speeches from Shakespeare Plays | Interesting Literature

- Pingback: Logic Has Nothing to Do with It | Pat Bean's blog

This post earned a Bean Pat as blog pick of the day. Check it out at https://patbean.net

In support of the revenge motive, Hamlet faces off against a powerful and popular king, albeit a usurper, who’s dangerous and also loved by his mother whose own motives are suspect. Claudius was more the politician/ruler and Hamlet the Renaissance scholar, one strong in arms, the other whose demise allowed Fortinbras (“strong in arms”) to invade and take over Denmark at the end. While Claudius was on the throne, Hamlet struggled to overthrow him until he was sure of his guilt. Part of the play’s genius is Claudius’ own soul-searching guilt that had Hamlet known, would have led to sooner action on the part of the prince. Throughout, as audience we are brought into the many deliberations knowing more than the characters inside the play know and wondering who we are as a result of Hamlet discovering himself. The opening words of the play tell it all: Who’s there?

I think you have to work hard to interpret this as not contemplating his fear of death and what lies beyond. That’s not to say the issue of revenge isn’t there – of course it is, Hamlet wouldn’t be contemplating death if not for the foul deed the ghost has laid before him!

As far as the stress on ‘that’ or ‘is’, I think this link should solve this… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEs8rK5Cqt8

Thanks, Ken. I absolutely agree that Hamlet is contemplating death here, but as you say, it’s his *fear* of death – and what awaits him afterwards – that lurks behind his words. If he chooses to ‘avenge’ his father and kill Claudius, and he’s been tricked by the Ghost and Claudius was innocent, hell awaits him. The fact that he refers to the afterlife as the ‘undiscover’d country, from whose bourn / No traveller returns’ when he’s recently been visited by a traveller who has returned (i.e. his father), suggests that he’s still doubting the truth of the Ghost. But this is perhaps partly why the lines have attained the status they have: they resist any narrowly reductive take that sees this as exclusively a ‘suicide speech’ (or similar). I may need to go and reread the play now…

I’ve just been working with the play with A level students recently so it is very fresh in my mind. I’ve grown to love the speech when, perhaps, I’ve tended to let ‘familiarity breed contempt’ in the past. It’s a superb rendering of anguish over a ‘do I, don’t I?’ situation which, of course, has eternal consequences. The Ghost also reveals there’s doubt over the ‘perchance to dream’ that death should be – what if Hamlet is to die and roam the Earth in torment like his father?! What would we choose, I wonder…

As an aside, and fearing ruining what little reputation I might have(!) – for my money the best Hamlet of all is Mel Gibson. I genuinely rate him over all the so-called ‘serious’ Shakespearean actors (yes, even over Olivier) and recommend his film version to all students who want a believable rather than stylised rendition of the character.

Reblogged this on Manolis .

Hamlet tells us what the speech is about in lines 2-5, where he explains what he means by “To be or not to be”. He means that there are two options for him: these options are: in lines 2-3, to put up with random unpleasantness from Claudius and others; in lines 4-5, to actually do something, viz. to take up arms, to fight, and possibly, within the context of the plot, to kill Claudius. As a result of killing Claudius, Hamlet might well die himself.

The natural meaning of “take arms against a sea of troubles” etc is to battle some exterior force; to grab weapons to do battle against the sea which is out there, not here, and certainly not inside us. Or, if the sea were metaphorically inside him, and were an interior enemy, he would need to make that clear, which he does not do. The meaning remains, imho, the clear and patent one, rather than a reference to suicide.

So the dilemma is to put up, or to take action; and this is set out clearly at the start. However, as you say, there is some shadow of suicide in the words of the first line too; and this shadow comes to life when the “bare bodkin” is mentioned later. The speech is about putting up (and choosing life), or not putting up (and maybe choosing death), and the implications of this choice in the next world and this one. Hovering above the text (or lurking beneath it) is the idea that suicide could be an option, too.

It’s always interesting to hear a new perspective on this soliloquy.

- Pingback: 15 Types Of Poems Every Writer Should Know About

- Pingback: Hamlet: Key Quotes Explained – Interesting Literature

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

Expert's Guide to the AP Literature Exam

Advanced Placement (AP)

If you're planning to take the AP English Literature and Composition exam, you'll need to get familiar with what to expect on the test. Whether the 2023 test date of Wednesday, May 3, is near or far, I'm here to help you get serious about preparing for the exam.

In this guide, I'll go over the test's format and question types, how it's graded, best practices for preparation, and test-day tips. You'll be on your way to AP English Lit success in no time!

AP English Literature: Exam Format and Question Types

The AP Literature Exam is a three-hour exam that contains two sections in this order:

- An hour-long, 55-question multiple-choice section

- A two-hour, three-question free-response section

The exam tests your ability to analyze works and excerpts of literature and cogently communicate that analysis in essay form.

Read on for a breakdown of the two different sections and their question types.

Section I: Multiple Choice

The multiple-choice section, or Section I of the AP Literature exam, is 60 minutes long and has 55 questions. It counts for 45% of your overall exam grade .

You can expect to see five excerpts of prose and poetry. You will always get at least two prose passages (fiction or drama) and two poetry passages. In general, you will not be given the author, date, or title for these works, though occasionally the title of a poem will be given. Unusual words are also sometimes defined for you.

The date ranges of these works could fall from the 16th to the 21st century. Most works will be originally written in English, but you might occasionally see a passage in translation.

There are, generally speaking, eight kinds of questions you can expect to see on the AP English Literature and Composition exam. I'll break each of them down here and give you tips on how to identify and approach them.

"Pretty flowers carried by ladies" is not one of the question types.

The 8 Multiple-Choice Question Types on the AP Literature Exam

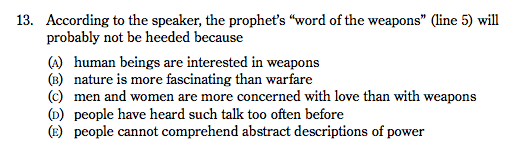

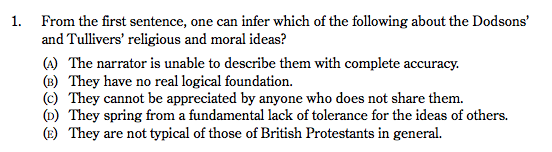

Without further delay, here are the eight question types you can expect to see on the AP Lit exam. All questions are taken from the sample questions on the AP Course and Exam Description .

#1: Reading Comprehension

These questions test your ability to understand what the passage is saying on a pretty basic level . They don't require you to do a lot of interpretation—you just need to know what's going on.

You can identify this question type from words and phrases such as "according to," "mentioned," "asserting," and so on. You'll succeed on these questions as long as you carefully read the text . Note that you might have to go back and reread parts to make sure you understand what the passage is saying.

#2: Inference

These questions ask you to infer something—a character or narrator's opinion, an author's intention, etc.—based on what is said in the passage . It will be something that isn't stated directly or concretely but that you can assume based on what's clearly written in the passage. You can identify these questions from words such as "infer" and "imply."

The key to these questions is to not get tripped up by the fact that you are making an inference—there will be a best answer, and it will be the choice that is best supported by what is actually found in the passage .

In many ways, inference questions are like second-level reading comprehension questions: you need to know not just what a passage says, but also what it means.

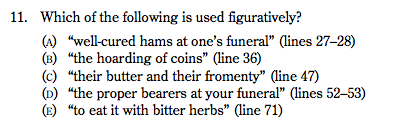

#3: Identifying and Interpreting Figurative Language

These are questions for which you have to either identify what word or phrase is figurative language or provide the meaning of a figurative phrase . You can identify these as they will either explicitly mention figurative language (or a figurative device, such as a simile or metaphor ) or include a figurative phrase in the question itself.

The meaning of figurative phrases can normally be determined by that phrase's context in the passage—what is said around it? What is the phrase referring to?

Example 1: Identifying

Example 2: Interpreting

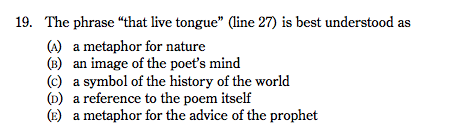

#4: Literary Technique

These questions involve identifying why an author does what they do , from using a particular phrase to repeating certain words. Basically, what techniques is the author using to construct the passage/poem, and to what effect?

You can identify these questions by words/phrases such as "serves chiefly to," "effect," "evoke," and "in order to." A good way to approach these questions is to ask yourself: so what? Why did the author use these particular words or this particular structure?

#5: Character Analysis

These questions ask you to describe something about a character . You can spot them because they will refer directly to characters' attitudes, opinions, beliefs, or relationships with other characters .

This is, in many ways, a special kind of inference question , since you are inferring the broader personality of the character based on the evidence in a passage. Also, these crop up much more commonly for prose passages than they do for poetry ones.

#6: Overall Passage Questions

Some questions ask you to identify or describe something about the passage or poem as a whole : its purpose, tone, genre, etc. You can identify these by phrases such as "in the passage" and "as a whole."

To answer these questions, you need to think about the excerpt with a bird's-eye view . What is the overall picture created by all the tiny details?

#7: Structure

Some AP Lit questions will ask you about specific structural elements of the passage: a shift in tone, a digression, the specific form of a poem, etc . Often these questions will specify a part of the passage/poem and ask you to identify what that part is accomplishing.

Being able to identify and understand the significance of any shifts —structural, tonal, in genre, and so on—will be of key importance for these questions.

#8: Grammar/Nuts & Bolts

Very occasionally you will be asked a specific grammar question , such as what word an adjective is modifying. I'd also include in this category super-specific questions such as those that ask about the meter of a poem (e.g., iambic pentameter).

These questions are less about literary artistry and more about the fairly dry technique involved in having a fluent command of the English language .

That covers the eight question types on the multiple-choice section. Now, let's take a look at the free-response section of the AP Literature exam.

Keep track of the nuts and bolts of grammar.

Section II: Free Response

The AP Literature Free Response section is two hours long and involves three free-response essay questions , so you'll have about 40 minutes per essay. That's not a lot of time considering this section of the test counts for 55% of your overall exam grade !

Note, though, that no one will prompt you to move from essay to essay, so you can theoretically divide up the time however you want. Just be sure to leave enough time for each essay! Skipping an essay, or running out of time so you have to rush through one, can really impact your final test score.

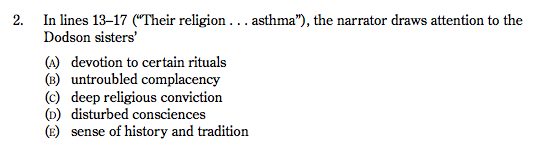

The first two essays are literary analysis essays of specific passages, with one poem and one prose excerpt. The final essay is an analysis of a given theme in a work selected by you , the student.

Essays 1 & 2: Literary Passage Analysis

For the first two essays, you'll be presented with an excerpt and directed to analyze the excerpt for a given theme, device, or development . One of the passages will be poetry, and one will be prose. You will be provided with the author of the work, the approximate date, and some orienting information (i.e., the plot context of an excerpt from a novel).

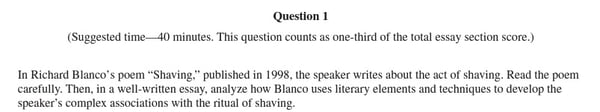

Below are some sample questions from the 2022 Free Response Questions .

Essay 3: Thematic Analysis

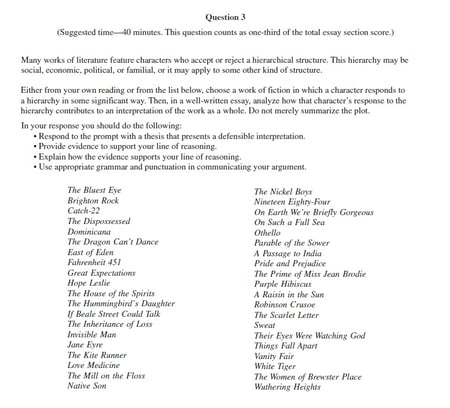

For the third and final essay, you'll be asked to discuss a particular theme in a work that you select . You will be provided with a list of notable works that address the given theme below the prompt, but you can also choose to discuss any "work of literary merit."

So while you do have the power to choose which work you wish to write an essay about , the key words here are "literary merit." That means no genre fiction! Stick to safe bets like authors in the list on pages 10-11 of the old 2014 AP Lit Course Description .

(I know, I know—lots of genre fiction works do have literary merit and Shakespeare actually began as low culture, and so on and so forth. Indeed, you might find academic designations of "literary merit" elitist and problematic, but the time to rage against the literary establishment is not your AP Lit test! Save it for a really, really good college admissions essay instead .)

Here's a sample question from 2022:

As you can see, the list of works provided spans many time periods and countries : there are ancient Greek plays ( Antigone ), modern literary works (such as Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale ), Shakespeare plays ( The Tempest ), 19th-century English plays ( The Importance of Being Earnest ), etc. So you have a lot to work with!

Also note that you can choose a work of "comparable literary merit." That means you can select a work not on this list as long as it's as difficult and meaningful as the example titles you've been given. So for example, Jane Eyre or East of Eden would be great choices, but Twilight or The Hunger Games would not.

Our advice? If you're not sure what a work of "comparable literary merit" is, stick to the titles on the provided list .

You might even see something by this guy.

How Is the AP Literature Test Graded?

The multiple-choice section of the exam comprises 45% of your total exam score; the three essays, or free-response section, comprise the other 55%. Each essay, then, is worth about 18% of your grade.

As on other AP exams, your raw score will be converted to a score from 1-5 . You don't have to get every point possible to get a 5 by any means. In 2022, 16.9% of students received 5s on the AP English Literature test, the 14th highest 5 score out of the 38 different AP exams.

So, how do you calculate your raw scores?

Multiple-Choice Scoring

For the multiple-choice section, you receive 1 point for each question you answer correctly . There's no guessing penalty, so you should answer every question—but guess only after you're able to eliminate any answer you know is wrong to up your chances of choosing the right one.

Free-Response Scoring

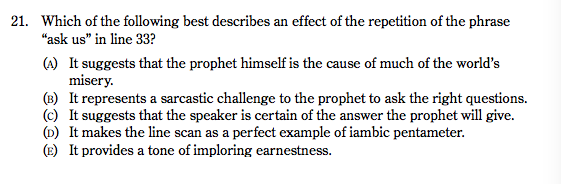

Scoring for multiple choice is pretty straightforward; however, essay scoring is a little more complicated.

Each of your essays will receive a score from 0 to 6 based on the College Board rubric , which also includes question-specific rubrics. All the rubrics are very similar, with only minor differences between them.

Each essay rubric has three elements you'll be graded on:

- Thesis (0-1 points)

- Evidence and Commentary (0-4 points)

- Sophistication (0-1 points)

We'll be looking at the current rubric for the AP Lit exam , which was released in September 2019, and what every score means for each of the three elements above:

To get a high-scoring essay in the 5-6 point range, you'll need to not only come up with an original and intriguing argument that you thoroughly support with textual evidence, but you’ll also need to stay focused, organized, and clear. And all in just 40 minutes per essay!

If getting a high score on this section sounds like a tall order, that's because it is.

Practice makes perfect!

Skill-Building for Success on the AP Literature Exam

There are several things you can do to hone your skills and best prepare for the AP Lit exam.

Read Some Books, Maybe More Than Once

One of the most important steps you can take to prepare for the AP Literature and Composition exam is to read a lot and read well . You'll be reading a wide variety of notable literary works in your AP English Literature course, but additional reading will help you further develop your analytical reading skills .

I suggest checking out this list of notable authors in the 2014 AP Lit Course Description (pages 10-11).

In addition to reading broadly, you'll want to become especially familiar with the details of four to five books with different themes so you'll be prepared to write a strong student-choice essay. You should know the plot, themes, characters, and structural details of these books inside and out.

See my AP English Literature Reading List for more guidance.

Read (and Interpret) Poetry

One thing students might not do very much on their own time but that will help a lot with AP Lit exam prep is to read poetry. Try to read poems from a lot of eras and authors to get familiar with the language.

We know that poetry can be intimidating. That's why we've put together a bunch of guides to help you crack the poetry code (so to speak). You can learn more about poetic devices —like imagery and i ambic pentameter —in our comprehensive guide. Then you can see those analytical skills in action in our expert analysis of " Do not go gentle into that good night " by Dylan Thomas.

When you think you have a grip on basic comprehension, you can then move on to close reading (see below).

Hone Your Close Reading and Analysis Skills

Your AP class will likely focus heavily on close reading and analysis of prose and poetry, but extra practice won't hurt you. Close reading is the ability to identify which techniques the author is using and why. You'll need to be able to do this both to gather evidence for original arguments on the free-response questions and to answer analytical multiple-choice questions.

Here are some helpful close reading resources for prose :

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center's guide to close reading

- Harvard College Writing Center's close reading guide

- Purdue OWL's article on steering clear of close reading "pitfalls"

And here are some for poetry :

- University of Wisconsin-Madison's poetry-reading guide

- This guide to reading poetry at Poets.org (complete with two poetry close readings)

- Our own expert analyses of famous poems, such as " Ozymandias ", and the 10 famous sonnets you should know

Learn Literary and Poetic Devices

You'll want to be familiar with literary terms so that any test questions that ask about them will make sense to you. Again, you'll probably learn most of these in class, but it doesn't hurt to brush up on them.

Here are some comprehensive lists of literary terms with definitions :

- The 31 Literary Devices You Must Know

- The 20 Poetic Devices You Must Know

- The 9 Literary Elements You'll Find In Every Story

- What Is Imagery?

- Understanding Assonance

- What Is Iambic Pentameter in Poetry?

- Simile vs Metaphor: The 1 Big Difference

- 10 Personification Examples in Poetry, Literature, and More

Practice Writing Essays

The majority of your grade on the AP English Lit exam comes from essays, so it's critical that you practice your timed essay-writing skills . You of course should use the College Board's released free-response questions to practice writing complete timed essays of each type, but you can also practice quickly outlining thorough essays that are well supported with textual evidence.

Take Practice Tests

Taking practice tests is a great way to prepare for the exam. It will help you get familiar with the exam format and overall experience . You can get sample questions from the Course and Exam Description , the College Board website , and our guide to AP English Lit practice test resources .

Be aware that the released exams don't have complete slates of free-response questions, so you might need to supplement these with released free-response questions .

Since there are three complete released exams, you can take one toward the beginning of your prep time to get familiar with the exam and set a benchmark, and one toward the end to make sure the experience is fresh in your mind and to check your progress.

Don't wander like a lonely cloud through your AP Lit prep.

AP Literature: 6 Critical Test-Day Tips

Before we wrap up, here are my six top tips for AP Lit test day:

- #1: On the multiple-choice section, it's to your advantage to answer every question. If you eliminate all the answers you know are wrong before guessing, you'll raise your chances of guessing the correct one.

- #2: Don't rely on your memory of the passage when answering multiple-choice questions (or when writing essays, for that matter). Look back at the passage!

- #3: Interact with the text : circle, mark, underline, make notes—whatever floats your boat. This will help you retain information and actively engage with the passage.

- #4: This was mentioned above, but it's critical that you know four to five books well for the student-choice essay . You'll want to know all the characters, the plot, the themes, and any major devices or motifs the author uses throughout.

- #5: Be sure to plan out your essays! Organization and focus are critical for high-scoring AP Literature essays. An outline will take you a few minutes, but it will help your writing process go much faster.

- #6: Manage your time on essays closely. One strategy is to start with the essay you think will be the easiest to write. This way you'll be able to get through it while thinking about the other two essays.

And don't forget to eat breakfast! Apron optional.

AP Literature Exam: Key Takeaways

The AP Literature exam is a three-hour test that includes an hour-long multiple-choice section based on five prose and poetry passages and with 55 questions, and a two-hour free-response section with three essays : one analyzing a poetry passage, one analyzing a prose passage, and one analyzing a work chosen by you, the student.

The multiple-choice section is worth 45% of your total score , and the free-response section is worth 55% . The three essays are each scored on a rubric of 0-6, and raw scores are converted to a final scaled score from 1 to 5.

Here are some things you can do to prepare for the exam:

- Read books and be particularly familiar with four to five works for the student-choice essays

- Read poetry

- Work on your close reading and analysis skills

- Learn common literary devices

- Practice writing essays

- Take practice tests!

On test day, be sure to really look closely at all the passages and really interact with them by marking the text in a way that makes sense to you. This will help on both multiple-choice questions and the free-response essays. You should also outline your essays before you write them.

With all this in mind, you're well on your way to AP Lit success!

What's Next?

If you're taking other AP exams this year, you might be interested in our other AP resources: from the Ultimate Guide to the US History Exam , to the Ultimate AP Chemistry Study Guide , to the Best AP Psychology Study Guide , we have tons of articles on AP courses and exams for you !

Looking for practice exams? Here are some tips on how to find the best AP practice tests . We've also got comprehensive lists of practice tests for AP Psychology , AP Biology , AP Chemistry , and AP US History .

Deciding which APs to take? Take a look through the complete list of AP courses and tests , read our analysis of which AP classes are the hardest and easiest , and learn how many AP classes you should take .

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

IMAGES

VIDEO