Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

How long does it take to write a dissertation, published by steve tippins on july 11, 2019 july 11, 2019.

Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 05:00 am

How long does it take to write a dissertation? The most accurate (and least helpful) answer is, it depends. Since that’s probably not the answer you’re looking for, I’ll use the rest of the article to address the realities of how long it takes to write a dissertation.

How Long Does It Take to Write a Dissertation?

Based on my experience, writing your dissertation should take somewhere between 13-20 months. These are average numbers based upon the scores of doctoral students that I have worked with over the years, and they generally hold true.

I have seen people take less time and more time, but I believe that with concerted effort, the 13-20 month timeframe is reasonable.

“Based on my experience, writing your dissertation should take somewhere between 13-20 months.”

University Requirements

Once you hit the dissertation stage, some schools require a minimum number of hours in the dissertation area before you can graduate. Many schools require the equivalent of one year of dissertation credits to graduate.

So, even if you can finish your dissertation in three months, you will still have to pay for nine more months of dissertation credits before you can graduate. However, unless research and writing is your superpower, I wouldn’t worry about having to pay extra tuition.

But this requirement does offer some insight into how long it takes to write a dissertation. Based on this requirement, it’s reasonable to expect that writing your dissertation will take a year of more. This is consistent with my experience.

However, this timeframe is based on several assumptions. First, I am assuming that you are continually working towards finishing your dissertation. This means that no family emergencies, funding conundrums, or work issues get in the way of completing. Second, there are no major changes in your dissertation committee. Third, you will have access to the data that you need.

Assuming these assumptions hold true, this article should give you a general idea of how long it might take to write your dissertation.

How Long Does it Take to Write A Dissertation? Stage-By-Stage

Let’s break down each stage of the dissertation writing process and how long it takes.

Prospectus

This is the hardest one to judge, as this is where you lay the groundwork for the rest of your dissertation and get buy-in from committee members. Normally this takes from 3-6 months. Not all of this is writing time, though–much of it is spent refining your topic and your approach.

Why does this stage take so long? For many people, starting to express themselves using an academic voice can take time. This can hold up the review process as your committee members ask for writing-related revisions before they even get to evaluating the content. Don’t worry, once you learn the academic language things will start to flow more easily.

One common mistake students make is lack of specificity, both in their writing in general and in their topic focus.

Proposal (Chapters 1-3)

Chapter 1 is often an expansion of your Prospectus. However, you’ll be expected to develop your ideas more and have even more specificity on things like your research question and methodology, so don’t underestimate how long this chapter will take.

Chapter 2 can take some time as you will be digging deep into the literature but I think this can be done in 3-4 months. One caution, some people, and committees, like to start with Chapter 2 so that you are immersed in the literature before completing Chapters 1 and 3. Regardless of where you start, 3-4 months is a good estimate.

Chapter 3 requires an in-depth explanation of your methodology. I suggest working closely with your Chair on this one to avoid multiple submissions and revisions. Get clear on your methodology and make sure you and your chair are on the same page before you write, and continue to check in with your chair, if possible, throughout the process.

IRB Approval

While this step can be full of details and require several iterations it seems that allowing 2 months is sufficient. Most schools have an IRB form that must be submitted. To save time you can usually start filling out the form while your committee is reviewing your Proposal.

Collecting Data

This step varies a great deal. If you are using readily available secondary data this can take a week but if you are interviewing hard to get individuals or have trouble finding a sufficient number of people for your sample this can take 4 months or more. I think 1-4 months should be appropriate

Chapters 4 and 5

These two chapters are the easiest to write as in Chapter 4 you are reporting your results and in Chapter 5 you explain what the results mean. I believe that these two chapters can be written in 2 months.

Defense and Completion

You will need to defend your dissertation and then go through all of the university requirements to finalize the completion of your dissertation. I would allow 2 months for this process.

Variables That Affect How Long It Takes to Write A Dissertation

When students say something like, “I’m going to finish my dissertation in three months,” they likely aren’t considering all of the variables besides the actual writing. Even if you’re a fast writer, you’ll have to wait on your committee’s comments,

Timing Issues

Many schools have response times for committee members. This is important when looking at how long it takes to finish a dissertation. For example, it you have two committee members and they each get up to 2 weeks for a review, it can take up to a month to get a document reviewed, each time you submit. So, plan for these periods of time when thinking about how long that it will take you.

Addressing Comments

How long it takes to write your dissertation also depends on your ability to address your committee’s comments thoroughly. It’s not uncommon for a committee member to send a draft back several times, even if their comments were addressed adequately, because they notice new issues each time they read it. Save yourself considerable time by making sure you address their comments fully, thus avoiding unnecessary time waiting to hear the same feedback.

This is the biggest variable in the dissertation model. How dedicated are you to the process? How much actual time do you have? How many outside interests/requirements do you have? Are you easily distracted? How clean does your workspace need to be? (This may seem like a strange thing to discuss, but many people need to work in a clean space and can get very interested in cleaning if they have to write). Are you in a full-time program or in a part time program? Are you holding down a job? Do you have children?

All of these things will affect how much time you have to put into writing–or rather, how disciplined you need to be about making time to write.

One of the things that can influence how long it takes to write your dissertation is your committee. Choose your committee wisely. If you work under the assumption that the only good dissertation is a done dissertation, then you want a committee that will be helpful and not trying to prove themselves on your back. When you find a Chair that you can work with ask her/him which of their colleagues they work well with (it’s also worth finding out who they don’t work well with).

Find out how they like to receive material to review. Some members like to see pieces of chapters and some like to see completed documents. Once you know their preferences, you can efficiently submit what they want when they want it.

How Long Does it Take to Write a Dissertation? Summary

Barring unforeseen events, the normal time range for finishing a dissertation seems to be 13-19 months, which can be rounded to one to one and a half years. If you are proactive and efficient, you can usually be at the shorter end of the time range.

That means using downtime to do things like changing the tense of your approved Proposal from future tense to past tense and completing things like you Abstract and Acknowledgement sections before final approval.

I hope that you can be efficient in this process and finish as quickly as possible. Remember, “the only good dissertation is a done dissertation.”

On that note, I offer coaching services to help students through the dissertation writing process, as well as editing services for those who need help with their writing.

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

Dissertation

Dissertation memes.

Sometimes you can’t dissertate anymore and you just need to meme. Don’t worry, I’ve got you. Here are some of my favorite dissertation memes that I’ve seen lately. My Favorite Dissertation Memes For when you Read more…

Surviving Post Dissertation Stress Disorder

The process of earning a doctorate can be long and stressful – and for some people, it can even be traumatic. This may be hard for those who haven’t been through a doctoral program to Read more…

PhD by Publication

PhD by publication, also known as “PhD by portfolio” or “PhD by published works,” is a relatively new route to completing your dissertation requirements for your doctoral degree. In the traditional dissertation route, you have Read more…

Frequently asked questions

How long does it take to write a dissertation.

At the bachelor’s and master’s levels, the dissertation is usually the main focus of your final year. You might work on it (alongside other classes) for the entirety of the final year, or for the last six months. This includes formulating an idea, doing the research, and writing up.

A PhD thesis takes a longer time, as the thesis is the main focus of the degree. A PhD thesis might be being formulated and worked on for the whole four years of the degree program. The writing process alone can take around 18 months.

Frequently asked questions: Knowledge Base

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research. Developing your methodology involves studying the research methods used in your field and the theories or principles that underpin them, in order to choose the approach that best matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. interviews, experiments , surveys , statistical tests ).

In a dissertation or scientific paper, the methodology chapter or methods section comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research , you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Harvard referencing uses an author–date system. Sources are cited by the author’s last name and the publication year in brackets. Each Harvard in-text citation corresponds to an entry in the alphabetised reference list at the end of the paper.

Vancouver referencing uses a numerical system. Sources are cited by a number in parentheses or superscript. Each number corresponds to a full reference at the end of the paper.

A Harvard in-text citation should appear in brackets every time you quote, paraphrase, or refer to information from a source.

The citation can appear immediately after the quotation or paraphrase, or at the end of the sentence. If you’re quoting, place the citation outside of the quotation marks but before any other punctuation like a comma or full stop.

In Harvard referencing, up to three author names are included in an in-text citation or reference list entry. When there are four or more authors, include only the first, followed by ‘ et al. ’

A bibliography should always contain every source you cited in your text. Sometimes a bibliography also contains other sources that you used in your research, but did not cite in the text.

MHRA doesn’t specify a rule about this, so check with your supervisor to find out exactly what should be included in your bibliography.

Footnote numbers should appear in superscript (e.g. 11 ). You can use the ‘Insert footnote’ button in Word to do this automatically; it’s in the ‘References’ tab at the top.

Footnotes always appear after the quote or paraphrase they relate to. MHRA generally recommends placing footnote numbers at the end of the sentence, immediately after any closing punctuation, like this. 12

In situations where this might be awkward or misleading, such as a long sentence containing multiple quotations, footnotes can also be placed at the end of a clause mid-sentence, like this; 13 note that they still come after any punctuation.

When a source has two or three authors, name all of them in your MHRA references . When there are four or more, use only the first name, followed by ‘and others’:

Note that in the bibliography, only the author listed first has their name inverted. The names of additional authors and those of translators or editors are written normally.

A citation should appear wherever you use information or ideas from a source, whether by quoting or paraphrasing its content.

In Vancouver style , you have some flexibility about where the citation number appears in the sentence – usually directly after mentioning the author’s name is best, but simply placing it at the end of the sentence is an acceptable alternative, as long as it’s clear what it relates to.

In Vancouver style , when you refer to a source with multiple authors in your text, you should only name the first author followed by ‘et al.’. This applies even when there are only two authors.

In your reference list, include up to six authors. For sources with seven or more authors, list the first six followed by ‘et al.’.

The words ‘ dissertation ’ and ‘thesis’ both refer to a large written research project undertaken to complete a degree, but they are used differently depending on the country:

- In the UK, you write a dissertation at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a thesis to complete a PhD.

- In the US, it’s the other way around: you may write a thesis at the end of a bachelor’s or master’s degree, and you write a dissertation to complete a PhD.

The main difference is in terms of scale – a dissertation is usually much longer than the other essays you complete during your degree.

Another key difference is that you are given much more independence when working on a dissertation. You choose your own dissertation topic , and you have to conduct the research and write the dissertation yourself (with some assistance from your supervisor).

Dissertation word counts vary widely across different fields, institutions, and levels of education:

- An undergraduate dissertation is typically 8,000–15,000 words

- A master’s dissertation is typically 12,000–50,000 words

- A PhD thesis is typically book-length: 70,000–100,000 words

However, none of these are strict guidelines – your word count may be lower or higher than the numbers stated here. Always check the guidelines provided by your university to determine how long your own dissertation should be.

References should be included in your text whenever you use words, ideas, or information from a source. A source can be anything from a book or journal article to a website or YouTube video.

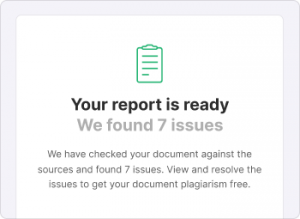

If you don’t acknowledge your sources, you can get in trouble for plagiarism .

Your university should tell you which referencing style to follow. If you’re unsure, check with a supervisor. Commonly used styles include:

- Harvard referencing , the most commonly used style in UK universities.

- MHRA , used in humanities subjects.

- APA , used in the social sciences.

- Vancouver , used in biomedicine.

- OSCOLA , used in law.

Your university may have its own referencing style guide.

If you are allowed to choose which style to follow, we recommend Harvard referencing, as it is a straightforward and widely used style.

To avoid plagiarism , always include a reference when you use words, ideas or information from a source. This shows that you are not trying to pass the work of others off as your own.

You must also properly quote or paraphrase the source. If you’re not sure whether you’ve done this correctly, you can use the Scribbr Plagiarism Checker to find and correct any mistakes.

In Harvard style , when you quote directly from a source that includes page numbers, your in-text citation must include a page number. For example: (Smith, 2014, p. 33).

You can also include page numbers to point the reader towards a passage that you paraphrased . If you refer to the general ideas or findings of the source as a whole, you don’t need to include a page number.

When you want to use a quote but can’t access the original source, you can cite it indirectly. In the in-text citation , first mention the source you want to refer to, and then the source in which you found it. For example:

It’s advisable to avoid indirect citations wherever possible, because they suggest you don’t have full knowledge of the sources you’re citing. Only use an indirect citation if you can’t reasonably gain access to the original source.

In Harvard style referencing , to distinguish between two sources by the same author that were published in the same year, you add a different letter after the year for each source:

- (Smith, 2019a)

- (Smith, 2019b)

Add ‘a’ to the first one you cite, ‘b’ to the second, and so on. Do the same in your bibliography or reference list .

To create a hanging indent for your bibliography or reference list :

- Highlight all the entries

- Click on the arrow in the bottom-right corner of the ‘Paragraph’ tab in the top menu.

- In the pop-up window, under ‘Special’ in the ‘Indentation’ section, use the drop-down menu to select ‘Hanging’.

- Then close the window with ‘OK’.

Though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there is a difference in meaning:

- A reference list only includes sources cited in the text – every entry corresponds to an in-text citation .

- A bibliography also includes other sources which were consulted during the research but not cited.

It’s important to assess the reliability of information found online. Look for sources from established publications and institutions with expertise (e.g. peer-reviewed journals and government agencies).

The CRAAP test (currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, purpose) can aid you in assessing sources, as can our list of credible sources . You should generally avoid citing websites like Wikipedia that can be edited by anyone – instead, look for the original source of the information in the “References” section.

You can generally omit page numbers in your in-text citations of online sources which don’t have them. But when you quote or paraphrase a specific passage from a particularly long online source, it’s useful to find an alternate location marker.

For text-based sources, you can use paragraph numbers (e.g. ‘para. 4’) or headings (e.g. ‘under “Methodology”’). With video or audio sources, use a timestamp (e.g. ‘10:15’).

In the acknowledgements of your thesis or dissertation, you should first thank those who helped you academically or professionally, such as your supervisor, funders, and other academics.

Then you can include personal thanks to friends, family members, or anyone else who supported you during the process.

Yes, it’s important to thank your supervisor(s) in the acknowledgements section of your thesis or dissertation .

Even if you feel your supervisor did not contribute greatly to the final product, you still should acknowledge them, if only for a very brief thank you. If you do not include your supervisor, it may be seen as a snub.

The acknowledgements are generally included at the very beginning of your thesis or dissertation, directly after the title page and before the abstract .

In a thesis or dissertation, the acknowledgements should usually be no longer than one page. There is no minimum length.

You may acknowledge God in your thesis or dissertation acknowledgements , but be sure to follow academic convention by also thanking the relevant members of academia, as well as family, colleagues, and friends who helped you.

All level 1 and 2 headings should be included in your table of contents . That means the titles of your chapters and the main sections within them.

The contents should also include all appendices and the lists of tables and figures, if applicable, as well as your reference list .

Do not include the acknowledgements or abstract in the table of contents.

To automatically insert a table of contents in Microsoft Word, follow these steps:

- Apply heading styles throughout the document.

- In the references section in the ribbon, locate the Table of Contents group.

- Click the arrow next to the Table of Contents icon and select Custom Table of Contents.

- Select which levels of headings you would like to include in the table of contents.

Make sure to update your table of contents if you move text or change headings. To update, simply right click and select Update Field.

The table of contents in a thesis or dissertation always goes between your abstract and your introduction.

An abbreviation is a shortened version of an existing word, such as Dr for Doctor. In contrast, an acronym uses the first letter of each word to create a wholly new word, such as UNESCO (an acronym for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization).

Your dissertation sometimes contains a list of abbreviations .

As a rule of thumb, write the explanation in full the first time you use an acronym or abbreviation. You can then proceed with the shortened version. However, if the abbreviation is very common (like UK or PC), then you can just use the abbreviated version straight away.

Be sure to add each abbreviation in your list of abbreviations !

If you only used a few abbreviations in your thesis or dissertation, you don’t necessarily need to include a list of abbreviations .

If your abbreviations are numerous, or if you think they won’t be known to your audience, it’s never a bad idea to add one. They can also improve readability, minimising confusion about abbreviations unfamiliar to your reader.

A list of abbreviations is a list of all the abbreviations you used in your thesis or dissertation. It should appear at the beginning of your document, immediately after your table of contents . It should always be in alphabetical order.

Fishbone diagrams have a few different names that are used interchangeably, including herringbone diagram, cause-and-effect diagram, and Ishikawa diagram.

These are all ways to refer to the same thing– a problem-solving approach that uses a fish-shaped diagram to model possible root causes of problems and troubleshoot solutions.

Fishbone diagrams (also called herringbone diagrams, cause-and-effect diagrams, and Ishikawa diagrams) are most popular in fields of quality management. They are also commonly used in nursing and healthcare, or as a brainstorming technique for students.

Some synonyms and near synonyms of among include:

- In the company of

- In the middle of

- Surrounded by

Some synonyms and near synonyms of between include:

- In the space separating

- In the time separating

In spite of is a preposition used to mean ‘ regardless of ‘, ‘notwithstanding’, or ‘even though’.

It’s always used in a subordinate clause to contrast with the information given in the main clause of a sentence (e.g., ‘Amy continued to watch TV, in spite of the time’).

Despite is a preposition used to mean ‘ regardless of ‘, ‘notwithstanding’, or ‘even though’.

It’s used in a subordinate clause to contrast with information given in the main clause of a sentence (e.g., ‘Despite the stress, Joe loves his job’).

‘Log in’ is a phrasal verb meaning ‘connect to an electronic device, system, or app’. The preposition ‘to’ is often used directly after the verb; ‘in’ and ‘to’ should be written as two separate words (e.g., ‘ log in to the app to update privacy settings’).

‘Log into’ is sometimes used instead of ‘log in to’, but this is generally considered incorrect (as is ‘login to’).

Some synonyms and near synonyms of ensure include:

- Make certain

Some synonyms and near synonyms of assure include:

Rest assured is an expression meaning ‘you can be certain’ (e.g., ‘Rest assured, I will find your cat’). ‘Assured’ is the adjectival form of the verb assure , meaning ‘convince’ or ‘persuade’.

Some synonyms and near synonyms for council include:

There are numerous synonyms and near synonyms for the two meanings of counsel :

AI writing tools can be used to perform a variety of tasks.

Generative AI writing tools (like ChatGPT ) generate text based on human inputs and can be used for interactive learning, to provide feedback, or to generate research questions or outlines.

These tools can also be used to paraphrase or summarise text or to identify grammar and punctuation mistakes. Y ou can also use Scribbr’s free paraphrasing tool , summarising tool , and grammar checker , which are designed specifically for these purposes.

Using AI writing tools (like ChatGPT ) to write your essay is usually considered plagiarism and may result in penalisation, unless it is allowed by your university. Text generated by AI tools is based on existing texts and therefore cannot provide unique insights. Furthermore, these outputs sometimes contain factual inaccuracies or grammar mistakes.

However, AI writing tools can be used effectively as a source of feedback and inspiration for your writing (e.g., to generate research questions ). Other AI tools, like grammar checkers, can help identify and eliminate grammar and punctuation mistakes to enhance your writing.

The Scribbr Knowledge Base is a collection of free resources to help you succeed in academic research, writing, and citation. Every week, we publish helpful step-by-step guides, clear examples, simple templates, engaging videos, and more.

The Knowledge Base is for students at all levels. Whether you’re writing your first essay, working on your bachelor’s or master’s dissertation, or getting to grips with your PhD research, we’ve got you covered.

As well as the Knowledge Base, Scribbr provides many other tools and services to support you in academic writing and citation:

- Create your citations and manage your reference list with our free Reference Generators in APA and MLA style.

- Scan your paper for in-text citation errors and inconsistencies with our innovative APA Citation Checker .

- Avoid accidental plagiarism with our reliable Plagiarism Checker .

- Polish your writing and get feedback on structure and clarity with our Proofreading & Editing services .

Yes! We’re happy for educators to use our content, and we’ve even adapted some of our articles into ready-made lecture slides .

You are free to display, distribute, and adapt Scribbr materials in your classes or upload them in private learning environments like Blackboard. We only ask that you credit Scribbr for any content you use.

We’re always striving to improve the Knowledge Base. If you have an idea for a topic we should cover, or you notice a mistake in any of our articles, let us know by emailing [email protected] .

The consequences of plagiarism vary depending on the type of plagiarism and the context in which it occurs. For example, submitting a whole paper by someone else will have the most severe consequences, while accidental citation errors are considered less serious.

If you’re a student, then you might fail the course, be suspended or expelled, or be obligated to attend a workshop on plagiarism. It depends on whether it’s your first offence or you’ve done it before.

As an academic or professional, plagiarising seriously damages your reputation. You might also lose your research funding or your job, and you could even face legal consequences for copyright infringement.

Paraphrasing without crediting the original author is a form of plagiarism , because you’re presenting someone else’s ideas as if they were your own.

However, paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you correctly reference the source . This means including an in-text referencing and a full reference , formatted according to your required citation style (e.g., Harvard , Vancouver ).

As well as referencing your source, make sure that any paraphrased text is completely rewritten in your own words.

Accidental plagiarism is one of the most common examples of plagiarism . Perhaps you forgot to cite a source, or paraphrased something a bit too closely. Maybe you can’t remember where you got an idea from, and aren’t totally sure if it’s original or not.

These all count as plagiarism, even though you didn’t do it on purpose. When in doubt, make sure you’re citing your sources . Also consider running your work through a plagiarism checker tool prior to submission, which work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts.

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker takes less than 10 minutes and can help you turn in your paper with confidence.

The accuracy depends on the plagiarism checker you use. Per our in-depth research , Scribbr is the most accurate plagiarism checker. Many free plagiarism checkers fail to detect all plagiarism or falsely flag text as plagiarism.

Plagiarism checkers work by using advanced database software to scan for matches between your text and existing texts. Their accuracy is determined by two factors: the algorithm (which recognises the plagiarism) and the size of the database (with which your document is compared).

To avoid plagiarism when summarising an article or other source, follow these two rules:

- Write the summary entirely in your own words by paraphrasing the author’s ideas.

- Reference the source with an in-text citation and a full reference so your reader can easily find the original text.

Plagiarism can be detected by your professor or readers if the tone, formatting, or style of your text is different in different parts of your paper, or if they’re familiar with the plagiarised source.

Many universities also use plagiarism detection software like Turnitin’s, which compares your text to a large database of other sources, flagging any similarities that come up.

It can be easier than you think to commit plagiarism by accident. Consider using a plagiarism checker prior to submitting your essay to ensure you haven’t missed any citations.

Some examples of plagiarism include:

- Copying and pasting a Wikipedia article into the body of an assignment

- Quoting a source without including a citation

- Not paraphrasing a source properly (e.g. maintaining wording too close to the original)

- Forgetting to cite the source of an idea

The most surefire way to avoid plagiarism is to always cite your sources . When in doubt, cite!

Global plagiarism means taking an entire work written by someone else and passing it off as your own. This can include getting someone else to write an essay or assignment for you, or submitting a text you found online as your own work.

Global plagiarism is one of the most serious types of plagiarism because it involves deliberately and directly lying about the authorship of a work. It can have severe consequences for students and professionals alike.

Verbatim plagiarism means copying text from a source and pasting it directly into your own document without giving proper credit.

If the structure and the majority of the words are the same as in the original source, then you are committing verbatim plagiarism. This is the case even if you delete a few words or replace them with synonyms.

If you want to use an author’s exact words, you need to quote the original source by putting the copied text in quotation marks and including an in-text citation .

Patchwork plagiarism , also called mosaic plagiarism, means copying phrases, passages, or ideas from various existing sources and combining them to create a new text. This includes slightly rephrasing some of the content, while keeping many of the same words and the same structure as the original.

While this type of plagiarism is more insidious than simply copying and pasting directly from a source, plagiarism checkers like Turnitin’s can still easily detect it.

To avoid plagiarism in any form, remember to reference your sources .

Yes, reusing your own work without citation is considered self-plagiarism . This can range from resubmitting an entire assignment to reusing passages or data from something you’ve handed in previously.

Self-plagiarism often has the same consequences as other types of plagiarism . If you want to reuse content you wrote in the past, make sure to check your university’s policy or consult your professor.

If you are reusing content or data you used in a previous assignment, make sure to cite yourself. You can cite yourself the same way you would cite any other source: simply follow the directions for the citation style you are using.

Keep in mind that reusing prior content can be considered self-plagiarism , so make sure you ask your instructor or consult your university’s handbook prior to doing so.

Most institutions have an internal database of previously submitted student assignments. Turnitin can check for self-plagiarism by comparing your paper against this database. If you’ve reused parts of an assignment you already submitted, it will flag any similarities as potential plagiarism.

Online plagiarism checkers don’t have access to your institution’s database, so they can’t detect self-plagiarism of unpublished work. If you’re worried about accidentally self-plagiarising, you can use Scribbr’s Self-Plagiarism Checker to upload your unpublished documents and check them for similarities.

Plagiarism has serious consequences and can be illegal in certain scenarios.

While most of the time plagiarism in an undergraduate setting is not illegal, plagiarism or self-plagiarism in a professional academic setting can lead to legal action, including copyright infringement and fraud. Many scholarly journals do not allow you to submit the same work to more than one journal, and if you do not credit a coauthor, you could be legally defrauding them.

Even if you aren’t breaking the law, plagiarism can seriously impact your academic career. While the exact consequences of plagiarism vary by institution and severity, common consequences include a lower grade, automatically failing a course, academic suspension or probation, and even expulsion.

Self-plagiarism means recycling work that you’ve previously published or submitted as an assignment. It’s considered academic dishonesty to present something as brand new when you’ve already gotten credit and perhaps feedback for it in the past.

If you want to refer to ideas or data from previous work, be sure to cite yourself.

Academic integrity means being honest, ethical, and thorough in your academic work. To maintain academic integrity, you should avoid misleading your readers about any part of your research and refrain from offences like plagiarism and contract cheating, which are examples of academic misconduct.

Academic dishonesty refers to deceitful or misleading behavior in an academic setting. Academic dishonesty can occur intentionally or unintentionally, and it varies in severity.

It can encompass paying for a pre-written essay, cheating on an exam, or committing plagiarism . It can also include helping others cheat, copying a friend’s homework answers, or even pretending to be sick to miss an exam.

Academic dishonesty doesn’t just occur in a classroom setting, but also in research and other academic-adjacent fields.

Consequences of academic dishonesty depend on the severity of the offence and your institution’s policy. They can range from a warning for a first offence to a failing grade in a course to expulsion from your university.

For those in certain fields, such as nursing, engineering, or lab sciences, not learning fundamentals properly can directly impact the health and safety of others. For those working in academia or research, academic dishonesty impacts your professional reputation, leading others to doubt your future work.

Academic dishonesty can be intentional or unintentional, ranging from something as simple as claiming to have read something you didn’t to copying your neighbour’s answers on an exam.

You can commit academic dishonesty with the best of intentions, such as helping a friend cheat on a paper. Severe academic dishonesty can include buying a pre-written essay or the answers to a multiple-choice test, or falsifying a medical emergency to avoid taking a final exam.

Plagiarism means presenting someone else’s work as your own without giving proper credit to the original author. In academic writing, plagiarism involves using words, ideas, or information from a source without including a citation .

Plagiarism can have serious consequences , even when it’s done accidentally. To avoid plagiarism, it’s important to keep track of your sources and cite them correctly.

Common knowledge does not need to be cited. However, you should be extra careful when deciding what counts as common knowledge.

Common knowledge encompasses information that the average educated reader would accept as true without needing the extra validation of a source or citation.

Common knowledge should be widely known, undisputed, and easily verified. When in doubt, always cite your sources.

Most online plagiarism checkers only have access to public databases, whose software doesn’t allow you to compare two documents for plagiarism.

However, in addition to our Plagiarism Checker , Scribbr also offers an Self-Plagiarism Checker . This is an add-on tool that lets you compare your paper with unpublished or private documents. This way you can rest assured that you haven’t unintentionally plagiarised or self-plagiarised .

Compare two sources for plagiarism

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organise your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organisation to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

Triangulation in research means using multiple datasets, methods, theories and/or investigators to address a research question. It’s a research strategy that can help you enhance the validity and credibility of your findings.

Triangulation is mainly used in qualitative research , but it’s also commonly applied in quantitative research . Mixed methods research always uses triangulation.

These are four of the most common mixed methods designs :

- Convergent parallel: Quantitative and qualitative data are collected at the same time and analysed separately. After both analyses are complete, compare your results to draw overall conclusions.

- Embedded: Quantitative and qualitative data are collected at the same time, but within a larger quantitative or qualitative design. One type of data is secondary to the other.

- Explanatory sequential: Quantitative data is collected and analysed first, followed by qualitative data. You can use this design if you think your qualitative data will explain and contextualise your quantitative findings.

- Exploratory sequential: Qualitative data is collected and analysed first, followed by quantitative data. You can use this design if you think the quantitative data will confirm or validate your qualitative findings.

An observational study could be a good fit for your research if your research question is based on things you observe. If you have ethical, logistical, or practical concerns that make an experimental design challenging, consider an observational study. Remember that in an observational study, it is critical that there be no interference or manipulation of the research subjects. Since it’s not an experiment, there are no control or treatment groups either.

The key difference between observational studies and experiments is that, done correctly, an observational study will never influence the responses or behaviours of participants. Experimental designs will have a treatment condition applied to at least a portion of participants.

Exploratory research explores the main aspects of a new or barely researched question.

Explanatory research explains the causes and effects of an already widely researched question.

Experimental designs are a set of procedures that you plan in order to examine the relationship between variables that interest you.

To design a successful experiment, first identify:

- A testable hypothesis

- One or more independent variables that you will manipulate

- One or more dependent variables that you will measure

When designing the experiment, first decide:

- How your variable(s) will be manipulated

- How you will control for any potential confounding or lurking variables

- How many subjects you will include

- How you will assign treatments to your subjects

There are four main types of triangulation :

- Data triangulation : Using data from different times, spaces, and people

- Investigator triangulation : Involving multiple researchers in collecting or analysing data

- Theory triangulation : Using varying theoretical perspectives in your research

- Methodological triangulation : Using different methodologies to approach the same topic

Triangulation can help:

- Reduce bias that comes from using a single method, theory, or investigator

- Enhance validity by approaching the same topic with different tools

- Establish credibility by giving you a complete picture of the research problem

But triangulation can also pose problems:

- It’s time-consuming and labour-intensive, often involving an interdisciplinary team.

- Your results may be inconsistent or even contradictory.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

In a between-subjects design , every participant experiences only one condition, and researchers assess group differences between participants in various conditions.

In a within-subjects design , each participant experiences all conditions, and researchers test the same participants repeatedly for differences between conditions.

The word ‘between’ means that you’re comparing different conditions between groups, while the word ‘within’ means you’re comparing different conditions within the same group.

A quasi-experiment is a type of research design that attempts to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. The main difference between this and a true experiment is that the groups are not randomly assigned.

In experimental research, random assignment is a way of placing participants from your sample into different groups using randomisation. With this method, every member of the sample has a known or equal chance of being placed in a control group or an experimental group.

Quasi-experimental design is most useful in situations where it would be unethical or impractical to run a true experiment .

Quasi-experiments have lower internal validity than true experiments, but they often have higher external validity as they can use real-world interventions instead of artificial laboratory settings.

Within-subjects designs have many potential threats to internal validity , but they are also very statistically powerful .

Advantages:

- Only requires small samples

- Statistically powerful

- Removes the effects of individual differences on the outcomes

Disadvantages:

- Internal validity threats reduce the likelihood of establishing a direct relationship between variables

- Time-related effects, such as growth, can influence the outcomes

- Carryover effects mean that the specific order of different treatments affect the outcomes

Yes. Between-subjects and within-subjects designs can be combined in a single study when you have two or more independent variables (a factorial design). In a mixed factorial design, one variable is altered between subjects and another is altered within subjects.

In a factorial design, multiple independent variables are tested.

If you test two variables, each level of one independent variable is combined with each level of the other independent variable to create different conditions.

While a between-subjects design has fewer threats to internal validity , it also requires more participants for high statistical power than a within-subjects design .

- Prevents carryover effects of learning and fatigue.

- Shorter study duration.

- Needs larger samples for high power.

- Uses more resources to recruit participants, administer sessions, cover costs, etc.

- Individual differences may be an alternative explanation for results.

Samples are used to make inferences about populations . Samples are easier to collect data from because they are practical, cost-effective, convenient, and manageable.

Probability sampling means that every member of the target population has a known chance of being included in the sample.

Probability sampling methods include simple random sampling , systematic sampling , stratified sampling , and cluster sampling .

In non-probability sampling , the sample is selected based on non-random criteria, and not every member of the population has a chance of being included.

Common non-probability sampling methods include convenience sampling , voluntary response sampling, purposive sampling , snowball sampling , and quota sampling .

In multistage sampling , or multistage cluster sampling, you draw a sample from a population using smaller and smaller groups at each stage.

This method is often used to collect data from a large, geographically spread group of people in national surveys, for example. You take advantage of hierarchical groupings (e.g., from county to city to neighbourhood) to create a sample that’s less expensive and time-consuming to collect data from.

Sampling bias occurs when some members of a population are systematically more likely to be selected in a sample than others.

Simple random sampling is a type of probability sampling in which the researcher randomly selects a subset of participants from a population . Each member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. Data are then collected from as large a percentage as possible of this random subset.

The American Community Survey is an example of simple random sampling . In order to collect detailed data on the population of the US, the Census Bureau officials randomly select 3.5 million households per year and use a variety of methods to convince them to fill out the survey.

If properly implemented, simple random sampling is usually the best sampling method for ensuring both internal and external validity . However, it can sometimes be impractical and expensive to implement, depending on the size of the population to be studied,

If you have a list of every member of the population and the ability to reach whichever members are selected, you can use simple random sampling.

Cluster sampling is more time- and cost-efficient than other probability sampling methods , particularly when it comes to large samples spread across a wide geographical area.

However, it provides less statistical certainty than other methods, such as simple random sampling , because it is difficult to ensure that your clusters properly represent the population as a whole.

There are three types of cluster sampling : single-stage, double-stage and multi-stage clustering. In all three types, you first divide the population into clusters, then randomly select clusters for use in your sample.

- In single-stage sampling , you collect data from every unit within the selected clusters.

- In double-stage sampling , you select a random sample of units from within the clusters.

- In multi-stage sampling , you repeat the procedure of randomly sampling elements from within the clusters until you have reached a manageable sample.

Cluster sampling is a probability sampling method in which you divide a population into clusters, such as districts or schools, and then randomly select some of these clusters as your sample.

The clusters should ideally each be mini-representations of the population as a whole.

In multistage sampling , you can use probability or non-probability sampling methods.

For a probability sample, you have to probability sampling at every stage. You can mix it up by using simple random sampling , systematic sampling , or stratified sampling to select units at different stages, depending on what is applicable and relevant to your study.

Multistage sampling can simplify data collection when you have large, geographically spread samples, and you can obtain a probability sample without a complete sampling frame.

But multistage sampling may not lead to a representative sample, and larger samples are needed for multistage samples to achieve the statistical properties of simple random samples .

In stratified sampling , researchers divide subjects into subgroups called strata based on characteristics that they share (e.g., race, gender, educational attainment).

Once divided, each subgroup is randomly sampled using another probability sampling method .

You should use stratified sampling when your sample can be divided into mutually exclusive and exhaustive subgroups that you believe will take on different mean values for the variable that you’re studying.

Using stratified sampling will allow you to obtain more precise (with lower variance ) statistical estimates of whatever you are trying to measure.

For example, say you want to investigate how income differs based on educational attainment, but you know that this relationship can vary based on race. Using stratified sampling, you can ensure you obtain a large enough sample from each racial group, allowing you to draw more precise conclusions.

Yes, you can create a stratified sample using multiple characteristics, but you must ensure that every participant in your study belongs to one and only one subgroup. In this case, you multiply the numbers of subgroups for each characteristic to get the total number of groups.

For example, if you were stratifying by location with three subgroups (urban, rural, or suburban) and marital status with five subgroups (single, divorced, widowed, married, or partnered), you would have 3 × 5 = 15 subgroups.

There are three key steps in systematic sampling :

- Define and list your population , ensuring that it is not ordered in a cyclical or periodic order.

- Decide on your sample size and calculate your interval, k , by dividing your population by your target sample size.

- Choose every k th member of the population as your sample.

Systematic sampling is a probability sampling method where researchers select members of the population at a regular interval – for example, by selecting every 15th person on a list of the population. If the population is in a random order, this can imitate the benefits of simple random sampling .

Populations are used when a research question requires data from every member of the population. This is usually only feasible when the population is small and easily accessible.

A statistic refers to measures about the sample , while a parameter refers to measures about the population .

A sampling error is the difference between a population parameter and a sample statistic .

There are eight threats to internal validity : history, maturation, instrumentation, testing, selection bias , regression to the mean, social interaction, and attrition .

Internal validity is the extent to which you can be confident that a cause-and-effect relationship established in a study cannot be explained by other factors.

Attrition bias is a threat to internal validity . In experiments, differential rates of attrition between treatment and control groups can skew results.

This bias can affect the relationship between your independent and dependent variables . It can make variables appear to be correlated when they are not, or vice versa.

The external validity of a study is the extent to which you can generalise your findings to different groups of people, situations, and measures.

The two types of external validity are population validity (whether you can generalise to other groups of people) and ecological validity (whether you can generalise to other situations and settings).

There are seven threats to external validity : selection bias , history, experimenter effect, Hawthorne effect , testing effect, aptitude-treatment, and situation effect.

Attrition bias can skew your sample so that your final sample differs significantly from your original sample. Your sample is biased because some groups from your population are underrepresented.

With a biased final sample, you may not be able to generalise your findings to the original population that you sampled from, so your external validity is compromised.

Construct validity is about how well a test measures the concept it was designed to evaluate. It’s one of four types of measurement validity , which includes construct validity, face validity , and criterion validity.

There are two subtypes of construct validity.

- Convergent validity : The extent to which your measure corresponds to measures of related constructs

- Discriminant validity: The extent to which your measure is unrelated or negatively related to measures of distinct constructs

When designing or evaluating a measure, construct validity helps you ensure you’re actually measuring the construct you’re interested in. If you don’t have construct validity, you may inadvertently measure unrelated or distinct constructs and lose precision in your research.

Construct validity is often considered the overarching type of measurement validity , because it covers all of the other types. You need to have face validity , content validity, and criterion validity to achieve construct validity.

Statistical analyses are often applied to test validity with data from your measures. You test convergent validity and discriminant validity with correlations to see if results from your test are positively or negatively related to those of other established tests.

You can also use regression analyses to assess whether your measure is actually predictive of outcomes that you expect it to predict theoretically. A regression analysis that supports your expectations strengthens your claim of construct validity .

Face validity is about whether a test appears to measure what it’s supposed to measure. This type of validity is concerned with whether a measure seems relevant and appropriate for what it’s assessing only on the surface.

Face validity is important because it’s a simple first step to measuring the overall validity of a test or technique. It’s a relatively intuitive, quick, and easy way to start checking whether a new measure seems useful at first glance.

Good face validity means that anyone who reviews your measure says that it seems to be measuring what it’s supposed to. With poor face validity, someone reviewing your measure may be left confused about what you’re measuring and why you’re using this method.

It’s often best to ask a variety of people to review your measurements. You can ask experts, such as other researchers, or laypeople, such as potential participants, to judge the face validity of tests.

While experts have a deep understanding of research methods , the people you’re studying can provide you with valuable insights you may have missed otherwise.

There are many different types of inductive reasoning that people use formally or informally.

Here are a few common types:

- Inductive generalisation : You use observations about a sample to come to a conclusion about the population it came from.

- Statistical generalisation: You use specific numbers about samples to make statements about populations.

- Causal reasoning: You make cause-and-effect links between different things.

- Sign reasoning: You make a conclusion about a correlational relationship between different things.

- Analogical reasoning: You make a conclusion about something based on its similarities to something else.

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach, while deductive reasoning is top-down.

Inductive reasoning takes you from the specific to the general, while in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

In inductive research , you start by making observations or gathering data. Then, you take a broad scan of your data and search for patterns. Finally, you make general conclusions that you might incorporate into theories.

Inductive reasoning is a method of drawing conclusions by going from the specific to the general. It’s usually contrasted with deductive reasoning, where you proceed from general information to specific conclusions.

Inductive reasoning is also called inductive logic or bottom-up reasoning.

Deductive reasoning is a logical approach where you progress from general ideas to specific conclusions. It’s often contrasted with inductive reasoning , where you start with specific observations and form general conclusions.

Deductive reasoning is also called deductive logic.

Deductive reasoning is commonly used in scientific research, and it’s especially associated with quantitative research .

In research, you might have come across something called the hypothetico-deductive method . It’s the scientific method of testing hypotheses to check whether your predictions are substantiated by real-world data.

A dependent variable is what changes as a result of the independent variable manipulation in experiments . It’s what you’re interested in measuring, and it ‘depends’ on your independent variable.

In statistics, dependent variables are also called:

- Response variables (they respond to a change in another variable)

- Outcome variables (they represent the outcome you want to measure)

- Left-hand-side variables (they appear on the left-hand side of a regression equation)

An independent variable is the variable you manipulate, control, or vary in an experimental study to explore its effects. It’s called ‘independent’ because it’s not influenced by any other variables in the study.

Independent variables are also called:

- Explanatory variables (they explain an event or outcome)

- Predictor variables (they can be used to predict the value of a dependent variable)

- Right-hand-side variables (they appear on the right-hand side of a regression equation)

A correlation is usually tested for two variables at a time, but you can test correlations between three or more variables.

On graphs, the explanatory variable is conventionally placed on the x -axis, while the response variable is placed on the y -axis.

- If you have quantitative variables , use a scatterplot or a line graph.

- If your response variable is categorical, use a scatterplot or a line graph.

- If your explanatory variable is categorical, use a bar graph.

The term ‘ explanatory variable ‘ is sometimes preferred over ‘ independent variable ‘ because, in real-world contexts, independent variables are often influenced by other variables. This means they aren’t totally independent.

Multiple independent variables may also be correlated with each other, so ‘explanatory variables’ is a more appropriate term.

The difference between explanatory and response variables is simple:

- An explanatory variable is the expected cause, and it explains the results.

- A response variable is the expected effect, and it responds to other variables.

There are 4 main types of extraneous variables :

- Demand characteristics : Environmental cues that encourage participants to conform to researchers’ expectations

- Experimenter effects : Unintentional actions by researchers that influence study outcomes

- Situational variables : Eenvironmental variables that alter participants’ behaviours

- Participant variables : Any characteristic or aspect of a participant’s background that could affect study results

An extraneous variable is any variable that you’re not investigating that can potentially affect the dependent variable of your research study.

A confounding variable is a type of extraneous variable that not only affects the dependent variable, but is also related to the independent variable.

‘Controlling for a variable’ means measuring extraneous variables and accounting for them statistically to remove their effects on other variables.

Researchers often model control variable data along with independent and dependent variable data in regression analyses and ANCOVAs . That way, you can isolate the control variable’s effects from the relationship between the variables of interest.

Control variables help you establish a correlational or causal relationship between variables by enhancing internal validity .

If you don’t control relevant extraneous variables , they may influence the outcomes of your study, and you may not be able to demonstrate that your results are really an effect of your independent variable .

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

In statistics, ordinal and nominal variables are both considered categorical variables .

Even though ordinal data can sometimes be numerical, not all mathematical operations can be performed on them.

In scientific research, concepts are the abstract ideas or phenomena that are being studied (e.g., educational achievement). Variables are properties or characteristics of the concept (e.g., performance at school), while indicators are ways of measuring or quantifying variables (e.g., yearly grade reports).

The process of turning abstract concepts into measurable variables and indicators is called operationalisation .

There are several methods you can use to decrease the impact of confounding variables on your research: restriction, matching, statistical control, and randomisation.

In restriction , you restrict your sample by only including certain subjects that have the same values of potential confounding variables.

In matching , you match each of the subjects in your treatment group with a counterpart in the comparison group. The matched subjects have the same values on any potential confounding variables, and only differ in the independent variable .

In statistical control , you include potential confounders as variables in your regression .

In randomisation , you randomly assign the treatment (or independent variable) in your study to a sufficiently large number of subjects, which allows you to control for all potential confounding variables.

A confounding variable is closely related to both the independent and dependent variables in a study. An independent variable represents the supposed cause , while the dependent variable is the supposed effect . A confounding variable is a third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables.

Failing to account for confounding variables can cause you to wrongly estimate the relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

To ensure the internal validity of your research, you must consider the impact of confounding variables. If you fail to account for them, you might over- or underestimate the causal relationship between your independent and dependent variables , or even find a causal relationship where none exists.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

No. The value of a dependent variable depends on an independent variable, so a variable cannot be both independent and dependent at the same time. It must be either the cause or the effect, not both.

You want to find out how blood sugar levels are affected by drinking diet cola and regular cola, so you conduct an experiment .

- The type of cola – diet or regular – is the independent variable .

- The level of blood sugar that you measure is the dependent variable – it changes depending on the type of cola.

Determining cause and effect is one of the most important parts of scientific research. It’s essential to know which is the cause – the independent variable – and which is the effect – the dependent variable.

Quantitative variables are any variables where the data represent amounts (e.g. height, weight, or age).

Categorical variables are any variables where the data represent groups. This includes rankings (e.g. finishing places in a race), classifications (e.g. brands of cereal), and binary outcomes (e.g. coin flips).

You need to know what type of variables you are working with to choose the right statistical test for your data and interpret your results .

Discrete and continuous variables are two types of quantitative variables :

- Discrete variables represent counts (e.g., the number of objects in a collection).

- Continuous variables represent measurable amounts (e.g., water volume or weight).

You can think of independent and dependent variables in terms of cause and effect: an independent variable is the variable you think is the cause , while a dependent variable is the effect .

In an experiment, you manipulate the independent variable and measure the outcome in the dependent variable. For example, in an experiment about the effect of nutrients on crop growth:

- The independent variable is the amount of nutrients added to the crop field.

- The dependent variable is the biomass of the crops at harvest time.

Defining your variables, and deciding how you will manipulate and measure them, is an important part of experimental design .

Including mediators and moderators in your research helps you go beyond studying a simple relationship between two variables for a fuller picture of the real world. They are important to consider when studying complex correlational or causal relationships.

Mediators are part of the causal pathway of an effect, and they tell you how or why an effect takes place. Moderators usually help you judge the external validity of your study by identifying the limitations of when the relationship between variables holds.

If something is a mediating variable :

- It’s caused by the independent variable

- It influences the dependent variable

- When it’s taken into account, the statistical correlation between the independent and dependent variables is higher than when it isn’t considered

A confounder is a third variable that affects variables of interest and makes them seem related when they are not. In contrast, a mediator is the mechanism of a relationship between two variables: it explains the process by which they are related.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

When conducting research, collecting original data has significant advantages:

- You can tailor data collection to your specific research aims (e.g., understanding the needs of your consumers or user testing your website).

- You can control and standardise the process for high reliability and validity (e.g., choosing appropriate measurements and sampling methods ).

However, there are also some drawbacks: data collection can be time-consuming, labour-intensive, and expensive. In some cases, it’s more efficient to use secondary data that has already been collected by someone else, but the data might be less reliable.

A structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions in a set order to collect data on a topic. They are often quantitative in nature. Structured interviews are best used when:

- You already have a very clear understanding of your topic. Perhaps significant research has already been conducted, or you have done some prior research yourself, but you already possess a baseline for designing strong structured questions.

- You are constrained in terms of time or resources and need to analyse your data quickly and efficiently

- Your research question depends on strong parity between participants, with environmental conditions held constant

More flexible interview options include semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

A semi-structured interview is a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews. Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uncomfortable.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. Participant answers can guide future research questions and help you develop a more robust knowledge base for future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview, but it is not always the best fit for your research topic.

Unstructured interviews are best used when:

- You are an experienced interviewer and have a very strong background in your research topic, since it is challenging to ask spontaneous, colloquial questions

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. While you may have developed hypotheses, you are open to discovering new or shifting viewpoints through the interview process.

- You are seeking descriptive data, and are ready to ask questions that will deepen and contextualise your initial thoughts and hypotheses

- Your research depends on forming connections with your participants and making them feel comfortable revealing deeper emotions, lived experiences, or thoughts

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.