The Psychological Impact of Parental Pressure on Kids and Teens

In this article.

Children and teenagers are struggling with mental health challenges like never before, and one factor that often contributes to their difficulties is excessive pressure from well-intentioned but misguided parents. Although it's understandable for parents to want their children to be happy and successful, pushing too hard can have serious negative consequences. This post explores the detrimental effects of parental pressure and offers strategies for providing healthy support and encouragement to help children thrive.

The Mental Health Consequences of Parental Pressure

Research shows that parental pressure, whether direct or indirect, can take a major toll on kids' psychological well-being. Some of the most common effects include:

- Depression and negative self-talk. Children who face frequent verbal criticism and unrealistic expectations from parents are at higher risk for depression. [1] They often internalize that criticism, engaging in harsh self-talk like "I'm stupid" or "I'll never be good enough."

- Eating disorders and body image issues. Kids and teens whose parents tease them about weight or police their eating habits are more likely to develop disordered eating and poor body image. [2] Even if well-intentioned, comments about appearance send the message that they're being judged.

- Academic underperformance. While parents often push kids academically in hopes of motivating them, studies find that children with controlling parents actually tend to do worse in school. [3] Constant pressure saps their intrinsic motivation.

- Social withdrawal. When affection and approval are conditional on meeting parental expectations, kids often start to withdraw. They may hide their true feelings, avoid asking for help, and struggle to form close relationships.

Why Parents Resort to Pressure

As damaging as parental pressure is, it usually comes from a place of love and concern. In one study, 86% of parents said they pressured their kids because they wanted to be more attentive than their own distant parents had been. [4] Others feel guilty about upheavals like divorce and try to compensate by pushing their kids to succeed.

Ultimately, most parents simply want the best for their children. But in our achievement-obsessed culture, it's easy to lose sight of what really matters for kids' long-term happiness and well-being. Pushing them to live up to an idealized vision of success often does more harm than good.

Strategies for Healthy Encouragement

So how can you support your child without resorting to unhealthy pressure? Here are some tips to keep in mind:

- Praise effort, not just achievements . Instead of only celebrating the "A," praise your child for studying hard or asking questions when confused. This builds confidence in their ability to overcome challenges. [5]

- Avoid appearance-based comments . Even "positive" remarks about looks can make kids self-conscious. Focus praise on things like kindness, curiosity, and perseverance instead.[2]

- Let them take the lead sometimes . Resist the urge to micromanage. Letting kids make age-appropriate choices builds their sense of autonomy and competence. [6]

- Validate their feelings . Remember, your child is a unique individual, not an extension of you. Listen to and acknowledge their perspective, even when it differs from yours. [7]

- Set collaborative rules . Kids are more likely to follow rules they had a voice in creating. Make expectations clear and consistent, but leave room for flexibility and discussion.

The Bottom Line

Parental pressure is incredibly common, but that doesn't make it harmless. Pushing your child to live up to rigid standards set by you, rather than supporting them in developing their own identity and goals, can lead to serious mental health issues that persist into adulthood.

The good news is, you have the power to break the cycle. By being mindful of how you communicate with your child, you can create an environment where they feel loved, respected, and empowered to grow into their best selves. It's not always easy, but your relationship with your child is worth the effort.

Common Questions

What is parental pressure.

Parental pressure refers to the emotional stress that parents impose on their children, often related to academic performance, extracurricular activities, social standards, appearance, and relationships. It can be direct (yelling, force) or indirect (guilt-tripping, rigid expectations).

Why do parents put pressure on their kids?

Most parents pressure their kids with good intentions, wanting them to be happy and successful. Some reasons include: wanting to be more attentive than their own distant parents, feeling guilty about life disruptions (divorce, moving), or believing their choices will make their child's life easier or more successful.

What are the mental health consequences of excessive parental pressure?

- Children who experience excessive parental pressure may develop:

- Depression and negative self-talk

- Eating disorders and body image issues

- Poor academic performance

- Social withdrawal and difficulty maintaining relationships

- Anger management problems and aggression

How can I tell if I'm pressuring my child too much?

Signs you might be pressuring your child include:

- Frequently criticizing or yelling at them

- Setting rigid expectations without their input

- Overreacting to mistakes or failures

- Withholding affection when they don't meet your standards

- Doing their work for them or intervening in their conflicts

What are some healthy ways to encourage my child without pressuring them?

Some strategies for healthy encouragement include:

- Praising effort and progress, not just end results

- Focusing on character traits, not appearance

- Allowing age-appropriate autonomy and choice

- Validating their feelings and perspective

- Setting clear, consistent rules collaboratively

Can I still have high expectations for my child without pressuring them?

Absolutely. The key is to communicate your expectations clearly and kindly, while also leaving room for your child's input and feelings. Emphasize growth and learning over perfection, and celebrate their efforts along the way.

What if my child is resistant to my encouragement?

If your child seems resistant, it might be a sign that they feel pressured or controlled. Try backing off a bit and focusing on rebuilding trust and connection. Let them know you're there to support them, but also respect their need for space and autonomy.

Where can I go for help if I'm struggling to break the cycle of parental pressure?

If you're having a hard time changing your parenting style, consider reaching out to a therapist or counselor who specializes in family dynamics and child development. They can provide guidance and support as you work on creating a more positive, nurturing relationship with your child.

- Wang, M.-T. and Kenny, S. (2014), Longitudinal Links Between Fathers’ and Mothers’ Harsh Verbal Discipline and Adolescents’ Conduct Problems and Depressive Symptoms. Child Dev, 85: 908-923. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12143

- Sprague, Stephanie Leigh. “Fat Talk with Parents and Weight Bias in High School and Undergraduate Students.” (2013). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Fat-Talk-with-Parents-and-Weight-Bias-in-High-and-Sprague/7a020e69316ffea32e7a814f3aeb44b2fbe1d13d

- Boggiano, Ann K. and Phyllis A. Katz. “Maladaptive Achievement Patterns in Students: The Role of Teachers' Controlling Strategies.” Journal of Social Issues 47 (1991): 35-51. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Maladaptive-Achievement-Patterns-in-Students%3A-The-Boggiano-Katz/d6ead7339aca2e06bb717d0629329c0d57b5a953

- Wolford, Sarah N et al. “Examining Parental Internal Processes Associated with Indulgent Parenting: A Thematic Analysis.” Journal of child and family studies vol. 29,3 (2020): 660-675. doi:10.1007/s10826-019-01612-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7731216/

- Kamins, M. L., & Dweck, C. S. (1999). Person versus process praise. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-05027-021

- Joussemet, Mireille et al. “Parenting and Self-Determination Theory 1 Running head: Parenting and Self-Determination Theory A Self-Determination Theory Perspective on Parenting.” (2019). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Parenting-and-Self-Determination-Theory-1-Running-A-Joussemet-Landry/37849173bd575690fde4d00699b5f137fd4c530f

- Joussemet, M., et al. (2008). Promoting optimal parenting and children's mental health. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257578835_Promoting_Optimal_Parenting_and_Children's_Mental_Health_A_Preliminary_Evaluation_of_the_How-to_Parenting_Program

Continue Reading

ADHD in the Workplace: How to Thrive in Your Career

ADHD in Women: Why It’s Often Misdiagnosed

ADHD and Exercise: How Physical Activity Can Improve Focus and Reduce Symptoms

Relational psych, pllc.

Essay on Parental Pressure

Students are often asked to write an essay on Parental Pressure in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Parental Pressure

Understanding parental pressure.

Parental pressure is when moms and dads expect their kids to meet high standards, often in school and other activities. They want the best for their children but may push too hard.

Effects on Children

Kids can feel stressed, anxious, or unhappy because of this pressure. They might worry a lot about disappointing their parents or feel like they can’t enjoy their hobbies or time with friends.

Finding Balance

Parents should encourage their kids without pushing too much. It’s important for children to try their best but also have fun and relax.

Communication is Key

Talking openly with each other can help. Kids can share their feelings, and parents can understand better, creating a happier family life.

250 Words Essay on Parental Pressure

What is parental pressure.

Parental pressure is when moms and dads expect their kids to do really well in different parts of life, especially school and sports. They often hope their children will achieve a lot, sometimes without realizing how tough they are being.

The Good Side

Sometimes, this pressure can be good because it pushes kids to work hard and be their best. Parents who encourage their children can help them to do well in school, which is important for a good future.

The Tough Side

But too much pressure can make kids feel stressed or scared. They might worry about disappointing their parents if they don’t get the best grades or win at sports. This can make kids unhappy and even make it hard for them to do well.

Balance is Key

It’s important for parents to find a balance. They should cheer on their kids and help them set goals, but also understand that making mistakes is part of learning. Kids need to know it’s okay to try their best and not be perfect.

In the end, it’s all about love and support. Parents should guide their children to do well, but also make sure they are happy and healthy. When moms and dads get this balance right, their kids can grow up feeling confident to take on the world.

500 Words Essay on Parental Pressure

Parental pressure is when moms and dads expect their kids to do really well in different areas of life, especially in school and other activities like sports or music. Sometimes, parents might want their children to reach the goals they themselves couldn’t achieve, or they think that pushing their kids will help them succeed in life.

Why Parents Push Their Kids

Parents often push their kids because they care a lot and want the best for them. They might believe that if they don’t push, their kids won’t try their hardest or will miss out on important chances in life. Some parents see other kids doing great things and they want their own kids to do just as well or even better.

The Good Side of Parental Pressure

A little bit of pressure from parents can be a good thing. It can help kids learn to work hard and stick with things, even when they get tough. This can help kids do better in school and prepare them for the real world. When parents support their kids and cheer them on, it can make kids feel loved and important.

The Bad Side of Parental Pressure

Too much pressure can be really stressful for kids. They might feel scared of making mistakes or worry all the time about not being good enough. This can make them unhappy and even make it harder for them to do well. Kids might also get tired because they’re trying to do too many things at once.

How Kids Feel

When parents put a lot of pressure on their kids, the kids can feel like they’re not good enough just the way they are. They might think they have to be perfect to make their parents happy. This can make them feel lonely or like they can’t talk to their parents about how they’re feeling.

It’s important for parents to find a balance. They should encourage their kids to try their best but also let them know it’s okay to make mistakes. Parents should listen to their kids and help them find things they love to do, not just things they have to do. This way, kids can learn and grow without feeling too much stress.

Parental pressure comes from a place of love, but it’s important to keep it in check. A little bit of encouragement can help kids succeed, but too much pressure can have the opposite effect. Parents should aim to guide their kids, not push them too hard. And kids should feel free to talk to their parents about how they feel. This way, everyone can work together to make sure that the pressure to do well is just right – not too much, and not too little.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Parental Involvement In Education

- Essay on Parental Consent For Abortion

- Essay on How Is Race A Social Construct

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Student Resources

- Teacher Resources

Effects of Parental Pressure on Students

Guadalupe Lopez

DC International PCS

Share Post:

In the relentless pursuit of perfection and parental approval, many students find themselves entangled in a web of parental pressure. In this essay, we will further explore the harm parental pressure can do to a child’s mental and emotional well-being. Parental pressure is very common around the world. It involves the expectations, guidance, and sometimes demands that parents place on their children to achieve certain goals, standards, or outcomes. I’m writing this essay in the hope that other students like me don’t feel alone in this situation and that their parents can understand how parental pressure affects their children and how they can support them. Parental pressure creates challenges, causing students to feel very pressured and depressed; therefore, parental organizations and school counselors should offer helpful programs and resources to parents to help them understand and support their kids better.

Parental pressure causes students to feel stressed out and less confident. The American Psychological Association states, “Young people internalize [parents’] expectations and depend on them for their self-esteem. And when they fail to meet them, as they invariably will, they’ll be critical of themselves for not matching up. To compensate, they strive to be perfect.” This proves that parental pressure can have many negative effects, like seeking validation, insecurities, and low self-esteem. Those negative effects could result in students wanting to give up on school and suffering from depression and anxiety during college and life beyond that if this problem isn’t resolved. Bay Atlantic University says, “Fear of failure stops students from taking up new projects or completing the ones at hand. In the hope of getting your validation for bringing home good grades, they will consider or even commit cheating to receive good compliments and rewards.” This shows that parental pressure can cause students to make poor decisions, such as academic cheating.

Mental health organizations and school counselors should provide parents with information sessions, counseling sessions, or resources for them to understand and support their kids better. According to The Center for Relationship Health, “Addressing parental pressure is a complex issue that requires collaboration among various organizations, including those focused on family well-being, education, mental health, and child advocacy.” This suggests that collaboration between these organizations and the involvement of parents, teachers, and communities is essential to creating a comprehensive approach to addressing parental pressure. Parental pressure is a varied issue that requires a holistic response involving educational, mental health, and advocacy organizations working together to promote healthier parenting practices and protect the well-being of children.

Some may argue that parental pressure is beneficial because it can improve academic performance, achievements, and personal growth. They might say that parental pressure can also be a source of motivation rather than a cause of stress and anxiety. According to the Department of Education, “Parental pressure on children to excel academically is helpful in motivating them to study.”

However, they don’t recognize that when parents set high expectations for their children, those expectations may be unrealistic, and this can have a range of negative consequences on teenagers, such as a strained relationship between parents and teenagers. They may struggle with decision-making in adult life because they relied on their parent’s expectations most of the time. According to Bay Atlantic University, “Although the pressure is mainly based on good intentions, sometimes parents can go beyond what’s acceptable for students. As a student, your child will constantly look for your validation. Even a slightly disappointed expression can send them into a bad mental state; they will start questioning their capabilities, slowly leading to fear, anxiety, and other mental illnesses.” This proves that although parental pressure can be a source of motivation, parents could push their children too hard, which can negatively impact students.

My own experiences with parental pressure have shaped my perspective on the importance of open communication and mutual understanding in families. In my junior year, I often felt like I had to be this perfect student while also being pressured to join a sport. I always tried to live up to those expectations, fearing that I might seem like a failure or not good enough. For example, my parents would praise an achieving student and athlete, and I would wonder if they wished they had someone like that as a daughter.

In conclusion, the impact of parental pressure on children and adolescents is a complex and significant issue that can have both positive and negative consequences. While some degree of parental guidance and encouragement is essential for a child’s development, excessive pressure and unrealistic expectations can be damaging to their mental and emotional well-being. It’s crucial to remember that, while well-intentioned, parental pressure can have significant long-term effects on children. By implementing these solutions, parents can create a nurturing, supportive, and loving environment that allows their children to flourish and develop into well-rounded individuals without the burden of excessive expectations.

Written By:

- Vishal's account

Parental Pressure on Children: Signs and Effects

What Is Parental Pressure?

Why do parents put pressure on their children, signs of parental pressure on kids, the effects of parental pressure on children, how to encourage your child without parental pressure.

Academic excellence has always been a symbol of pride and status in our society; however, it is a class divide among children that adults drive entirely. It’s bad enough that their future holds a cutthroat world where success is measured by how much money they make; on top of that, undue parental pressure on children to score high marks and show excellence in every subject makes their minds a boiling pot ready to burst.

Parents, of course, envision a bright and happy future for their children, and the knowledge of how competitive it is makes them push their wards to do well in every field. However, growing parental pressure on children’s academic excellence has become a grave concern.

Parental pressure refers to the expectations and demands parents place on their children to achieve certain goals, often related to academics, sports, extracurricular activities, or behaviour. This pressure can stem from parents’ desires for their children to succeed, their unfulfilled ambitions, or societal and cultural expectations (1) .

The dismal condition of our education system and the swelling volume of applicants each year is a stress point for most parents. Educational institutes always look for the best and brightest students to maintain their rankings, which ultimately percolates to the children through parental pressure. Protecting their child from a lifetime of regrets and heart-breaking rejections is a parent’s prerogative; however, sometimes, they raise the stakes too high for children to cope with.

Social standing is a big cause of parental pressure. Caring more about how the world perceives them, can render parents ignorant about the true talents of their children. It’s important to remember that success and excellence are not one-size-fits-all. Parents often generalise these terms, depending on how others are doing. This can lead to children feeling overwhelmed and underappreciated in areas of their own interests like arts, music, theatre, especially in sports.

Unfortunately, parental pressure in sports is common, ultimately making children give up on their talents. Competitive exams, institutional elitism, and the race for a plush job have created an unhealthy culture in which children are stunted instead of flourishing.

Though based on good intentions, parental pressure is often mistaken as care and can seriously affect children. A little bit of extra attention can reveal alarming behavioural signs (2) :

1. Nightmares

Children often reflect on their fears in sleep. Examination fever or not being able to get sound sleep could be signs of parental pressure.

2. Seclusion & Cheating

Children under stress are more likely to shut everyone out. If a child stops talking about school or ignores important information like mark sheets, examination schedules, or school grades, it could be because they are scared to let their parents down. This fear can make children resort to unhealthy practices like cheating in examinations.

3. Lethargy & Loss of Interest

The constant fear of falling short of parental expectations can be tiring, leaving a child lethargic and disinterested. It is definitely a red flag if your child loses interest in an extracurricular activity that he/she otherwise enjoyed. Losing interest in extracurricular activities could also cause physiological symptoms like stomach pain , headaches , and diarrhoea .

4. Late Hours

Parental pressure can push children into panic mode, keeping them up late into the night to achieve what is expected of them. It often hampers their retention power, making the whole activity futile.

5. Bad Temper

When a well-behaved child suddenly starts to fly off the handle at the slightest instigation, it is time to pay attention to his stress levels. Stress causes anger, and this is true for adults as well as children. If the child feels that his efforts are not good enough for his parents, it can cause a great deal of stress, resulting in a bad temper.

The signs that your child might be under parental pressure are less prominent than signs of stress in adults. Unlike adults, children are not vocal about these symptoms mostly because they are conditioned into thinking that their failure is causing the stress. Long-term subjugation of children to parental pressure can push them beyond recovery. Here are a few dangerous effects of parental pressure on children:

1. Prone to Mental Disease

Children who go unnoticed while dealing with an internal tussle between expectations and capabilities are more likely to succumb to mental diseases. Students often slip into depression or other diseases related to the mind, not knowing how to deal with it due to constant goal-setting by their parents.

2. Self-Harm

Children, especially during their teens, often resort to self-harming activities to deal with parental pressure. Studies show that children contemplate suicide as an answer to deal with parental disappointment due to low scores in examinations. In India, especially, deaths caused by suicide are unnaturally common among students, and no one needs to look further than the news reports received right after exam results to realise this truth.

3. Low Self-Esteem

Children mostly look at their parents for validation on everything they do, but if they meet with constant criticism from the other side, it most likely will create a negative self-image. This negative perception can transform into self-hate and hinder children from growing into well-adjusted adults.

4. Defensive Attitude

Constant parental pressure can create a defensive attitude in children. Fear of failure can stop them from taking up new projects or completing them. It can create unhealthy defiance in them that can lead to dissatisfied adulthood.

5. Risk of Permanent Injuries

Children who are made to bear the burden of excessive parental pressure while dealing with the physically and mentally taxing requirements of professional sports are more likely to push themselves over the threshold. They tend to ignore the pain and hurt, causing permanent injuries.

The pressure parents put on their children can significantly influence their development and well-being. Encouraging your child without applying undue parental pressure is essential for their healthy development and self-esteem. Here are some strategies to encourage your child positively:

1. Focus on Effort, Not Just Results

Praise your child for their hard work, dedication, and improvement rather than solely on the outcomes. This helps them develop a growth mindset, understanding that effort leads to progress and success (3) .

2. Set Realistic and Achievable Goals

Work with your child to set challenging yet attainable goals. Ensure these goals align with their interests and capabilities. This approach prevents overwhelming feelings and fosters a sense of accomplishment when they achieve these targets.

3. Provide a Supportive Environment

Create an environment where your child feels safe to express their feelings, interests, and concerns. Be an active listener and show empathy towards their experiences. This supportive atmosphere helps them feel valued and understood, reducing stress and anxiety.

4. Encourage Decision-Making

Allow your child to make their own choices regarding their activities and interests. Offer guidance and advice, but let them take the lead. This autonomy builds their confidence and teaches responsibility as they learn to make decisions and face the consequences.

5. Celebrate Individual Strengths and Interests

Recognise and celebrate your child’s unique talents and passions, even if they differ from your expectations. Encourage them to pursue what they love, whether academics, sports, arts, or any other.

1. How can parental pressure affect the parent-child relationship?

Excessive pressure can strain the parent-child relationship , leading to feelings of resentment and mistrust. Children may feel misunderstood and unsupported, causing emotional distance. Over time, this can erode the bond between parent and child, making open communication and mutual respect more difficult.

2. How does parental pressure contribute to the development of perfectionism in children?

Parental pressure often sets unrealistic standards for children, leading them to develop perfectionistic tendencies. This constant pursuit of flawlessness can result in heightened anxiety, fear of failure, and a diminished sense of self-worth.

3. How does parental pressure affect students’ academic performance?

Parental pressure on students’ academic performance can have positive and negative effects. While some students may feel motivated to excel under their parents’ expectations, excessive pressure can lead to detrimental outcomes. Students may experience heightened stress, anxiety, and a fear of failure, ultimately hindering their ability to perform well academically (4) .

4. How can parents recognise the fine line between healthy encouragement and detrimental pressure in their parenting approach?

Recognising the fine line between healthy encouragement and detrimental pressure requires mindfulness and self-awareness on the part of parents. It involves paying attention to their child’s cues, respecting their needs and limitations, and adjusting their approach. Open communication, empathy, and a willingness to prioritise their child’s well-being over external expectations are essential in finding this balance.

Parental pressure on students can significantly impact their academic performance, mental health, and overall well-being. As a parent, you must create a healthy space for your child to flourish and excel in life. You should discover your child’s strengths and guide them in enhancing their talents. Each child doesn’t need to achieve academic excellence. Success is inevitable if you give your child the required support to pursue their dreams in whichever field they want without instilling the fear of failure.

References/Resources:

1. Moneva. J. C, Moncada. K. A; Parental Pressure and Students Self-Efficacy; ResearchGate; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339096621_Parental_Pressure_and_Students_Self-Efficacy_1 ; January 2020

2. Impact Of Parental Pressure On Creativity And Self Efficacy Of Young Adults; IJCRT; https://ijcrt.org/papers/IJCRT2306199.pdf ; June 2023

3. How to Motivate Children: Science-Based Approaches for Parents, Caregivers, and Teachers; The Center on the Developing Child; https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/how-to-motivate-children-science-based-approaches-for-parents-caregivers-and-teachers/

4. Srivastava. A; Impact of Parental Pressure on Academic Achievement; ResearchGate; https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344137451_Impact_of_Parental_Pressure_on_Academic_Achievement

How to Raise a Tech Savvy Child? Parenting an Overly Competitive Child Habits That Parents Must Quit for Their Children Why You Should Stop Comparing Your Kid to Others

- RELATED ARTICLES

- MORE FROM AUTHOR

Kids Can Be Anything They Want to Be - Don't Judge them!

Premature White and Grey Hair in Kids

7 WORST Foods for Your Child’s Teeth That You Must Keep in Mind This Festive Season

Warning Signs of Helicopter Parents and Its Effects on Children

Caring for a Sick Child - Useful Tips for Parents

14 Best Home Remedies for Fever in Children

Popular on parenting.

245 Rare Boy & Girl Names with Meanings

22 Short Moral Stories in English For Kids

170 Boy & Girl Names That Mean 'Gift from God'

800+ Cool & Cute Nicknames for Boys & Girls

Latest posts.

34 Heartfelt Birthday Prayers for Husband

Homeschooling Preschooler - An Ultimate Guide for Parents

90 Special 13th Wedding Anniversary Messages, Wishes and Quotes for Husband and Wife

20 Must-Watch Animal Shows for Kids

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Raising Kids

- Parenting Advice

The Dangers of Putting Too Much Pressure on Kids

While it's normal to set high expectations for your children, putting them under too much pressure can be harmful to their mental health.

What Parental Pressure Looks Like

- When Pressure Is Harmful

- What to Do Instead

Most parents want their children to be the best they can be. However, some caregivers put too much pressure on their kids. Being under such intense pressure can have serious consequences, ranging from mental health problems to lowered self-esteem.

Learn more about the risks of parental pressure and how to motivate your kids without causing distress.

A survey by the Pew Research Center found that 64% of Americans say parents don't put enough pressure on children to do well in school . Some children might be less likely to perform their best if they don't get enough pressure from their parents.

That said, other kids might be under too much pressure. Adults have also expressed concerns that kids today "can't be kids anymore" because they're pressured and expected to constantly perform well—such as getting into the most prestigious schools or getting the best scholarships.

Parental Pressure in Sports and Other Activities

School isn’t the only place where parents put pressure on kids. Parents might also put lofty expectations on their kids to perform well in sports, music, theater, or other activities. "High-pressure parents" might insist that their kids practice constantly and perform well in competitions.

Every parent has a different approach to encouraging their kids. While high expectations can be healthy, placing constant pressure on children can be harmful. When kids feel like each homework assignment is going to make or break their future—or that each soccer game could determine if they get a college scholarship—that pressure can have negative consequences.

When Pressure From Parents Is Harmful

Kids who feel that they're under enormous pressure to do well can experience consequences in multiple areas of their lives, from their mental health to their sleep. Here are some effects of putting kids under too much pressure to perform.

Higher rates of mental illness

Kids who feel like they’re under constant pressure can experience constant anxiety. High amounts of stress can also place children at a greater risk of developing depression or other mental health conditions .

Higher risk of injuries

Athletes who feel a lot of pressure to be the best might continue to participate in sports despite injuries. Ignoring pain or returning to a sport before an injury has healed could lead to permanent damage.t

Increased likelihood of cheating

When the focus is on achievement rather than learning, kids are more likely to cheat. Whether it’s a young child catching a glimpse of a classmate's answer on a test, or a college student paying someone to write a term paper, cheating is common among kids who feel pressure to perform well.

Refusing to participate

When kids feel the goal is to always “be the best,” they’re not likely to participate when they aren’t likely to shine. A child who isn’t the fastest runner might quit playing soccer and a child who isn’t the best singer in the group might stop performing with the choir. Kids may also refuse to go to school if they don't excel. Unfortunately, that means kids won’t take opportunities to sharpen their skills.

Self-esteem problems

Pushing kids to excel can damage their self-esteem . The constant stress of performing interferes with children’s identity formation and causes them to feel like they’re not good enough—or even that they will never be good enough.

Sleep deprivation

Kids who feel constant pressure to do well in school might stay up late studying and struggle to get enough sleep. Or the excess pressure may be causing stress that makes it hard to sleep.

What to Do Instead of Adding Parental Pressure

Here's how parents can help their children without placing too much pressure on them.

- Encourage your child to do their best. Focus on the process, rather than the result.

- If you find yourself placing too much pressure on your child, ask yourself why their performance, test score, or success matters to you so much.

- Talk to your child about the sport/assignment/performance they're working on. Set aside your feelings to make room for your child to express theirs. Giving your child the space to be seen and heard will encourage them rather than make them feel they have disappointed you.

Americans say kids need more pressure in school, Chinese say less. Pew Research Center . 2013.

The influence of academic pressure on adolescents' problem behavior: Chain mediating effects of self-control, parent-child conflict, and subjective well-being . Front Psychol . 2022.

Parental Support and Adolescents' Coping with Academic Stressors: A Longitudinal Study of Parents' Influence Beyond Academic Pressure and Achievement . J Youth Adolesc . 2023.

Parents' Response to Children's Performance and Children's Self-Esteem: Parent-Child Relationship and Friendship Quality as Mediators. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2022.

Preventing Childhood Toxic Stress: Partnering With Families and Communities to Promote Relational Health . Pediatrics . 2021.

Related Articles

Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development

Do you wonder how parents influence their child? Read our parents’ influence on a child essay example and learn about the parental impact on behavior and development.

Introduction

- Financial Resources

- Education Level

Unemployed Parents

- Involvement of Parents

- Support from Parents

- Understanding of the Child’s Future

- Motivation from Parents

- Parental Goal-Setting

- The Importance of Discipline

Parents are means of structuring their child’s future. They have a very crucial role to play in their child’s growth and his/her conduct. During the days when schooling was considered to be accessible only to the children of the opulent, those who were not privileged enough to go to school, remained at home and helped their parents in daily chores.

Such children used to emulate their parents in their deeds and conduct. “In large part, we as children are shaped by what we see our parents do and how we see them act. I know that I have tried to model after my parents in many ways because I think they have done many things right” (Enotes, 2010).

But during the years, owing to the numerous opportunities available, parents have started devoting more time towards their work. Moreover, education has been simplified and has easy access. Children have started going to schools and as such, both parents and their children don’t have enough time to spend with each other. But still there are parents who devote time towards their children and try and teach them.

It has been observed that children, who have their parents’ guidance and participation in their school activities, achieve more in life as compared to those who totally depend on their schools. “…is that when parents get involved in their children’s education, they offer not only information specific to the classroom, but likely help in giving children a broader level of academic information” (Jeynes, 2011).

There are a few factors related to parents that have a major role to play in the child’s upbringing and education. These are:

Financial resources of parents

Financial resources mean the income of the parents. If the income of parents is good, they can afford to provide extra study material to their child at home. There is a lot of referencing material required by children and as such parents earning better can provide their child with books, periodicals, magazines, etc. Technological devices like the computer play an important role in a child’s standard of education. Parents earning handsomely can provide their child with a computer at home so that he/she can complete online projects. “Poverty takes a toll on students’ school performance. Poor children are twice as likely as their more affluent counterparts to repeat a grade; to be suspended, expelled, or drop out of high school; and to be placed in special education classes” (Education).

Education level of the parents

If the parents are well educated, they ought to understand the importance of education and will encourage their child to study better and up to high levels. Uneducated or less educated parents will not be able to understand the importance of moulding their child’s career from the early school days. On the contrary, well educated parents will understand that for achieving success and objectives, the foundation of their child should be strong.

Unemployed parents are disgruntled and as such the atmosphere at home is not conducive for a child to study. Children find it suffocating at home and as such can’t concentrate on their studies even at their schools. Nicole Biedinger remarked that “…it is hypothesized that the home environment and family background are very important for the cognitive abilities and for their improvement” (Biedinger 2011). He further continues that “Previous research has shown that there exist developmental differences of children from different social classes” (Biedinger, 2011).

Involvement of parents

It will not be contradictory to state that parents and schools have an equal effect on the development of children. Both have an important role to play and are links to a child’s future. Even if one of the links is missing, it will have a negative impact on the child. Parents can get involved in their child’s upbringing by keeping a constant vigil on his/her school work. They can also visit his/her school on occasions such as parent-teacher meetings, annual days, sport events, social get-togethers, etc. All this will help in developing confidence in the child and also a sense of safety and protection.

Once a child is grown up, the parents can still contribute towards building their child’s confidence and identifying his/her qualities by talking to him/her on various career related issues.

Support from parents

Even if parents are not able to contribute financially by providing the essential tools for education, they can at least act as moral boosters for their child. They can inculcate, in their child, the habit of studying hard in order to attain success in life. Such children can defy all odds and prove to fulfil their parents’ aspirations. Alison Rich emphasized that “A cognitively stimulating home need not be one that is rich in material resources. Parents can simply discuss issues of importance with their children, talk to them about what they are doing in school, or spend time doing activities that will develop their skills and abilities” (Rich, 2000).

Parents’ understanding of their child’s future

Simply by getting involved in their child’s school activities, parents cannot guarantee their child’s success. Parents should be well acquainted with the ongoing educational process and various courses available. Information on when to go for any particular course is very crucial. As for example, parents must be aware of any courses that their child might require before going to the college. There are various pre-college courses that improve the grasping power of students. Further, a child will not be able to tell as to what he/she wants to achieve in life. But parents, by knowing his/her interests, can assess their child’s inclination and can further encourage him/her to pursue those interests.

Motivation from parents

Usually, parents tell bed-time stories to their children. These stories have a great impact on the way a child thinks and are instrumental to quite some extent in moulding his/her behaviour and conduct. So parents should tell such stories that have some moral values. The child will get inspired from them and behave accordingly. Stories of heroes and successful people will encourage the child to be like one of them. Parents can also motivate their children by doing good acts themselves.

Parents to set goals for their child

Achieving one’s goals in life is a very important factor of success. Success comes to those who achieve their aims and objectives. Even though there are no fixed parameters for achieving success, it solely depends on the hard work, enthusiasm and motivation of a person. These qualities don’t come instantly but have to be nurtured since childhood. So parents, who want their child to succeed, should start giving him/her small targets to be completed in a given time-frame. Gradually, the child will be habituated to achieve targets and this will be helpful to a great extent in his/her future life, may it be his/her education or career.

Inculcating the importance of discipline

Being disciplined is one of the most critical requirements of being successful. Similar to the habit of achieving targets, discipline also doesn’t come instantly. It has to be inculcated since childhood.

Parents can teach discipline to their child by following certain rules. They can have strict time frames for different activities of their child at home such as study hours, watching the television programmes, having supper and other meals, and going to bed. A sense of responsibility can also be imposed on the child by allocating to him/her certain house-hold tasks.

Having mentioned all the above factors, it can be concluded that parents have an ever-lasting impact on their child’s education. It has been observed that in cases where parents have involvement in their children’s education, the children portray the following virtues: better grades at school, better rates of graduation, fewer absentees from school, better inspiration and confidence, abstaining from drugs, smoking, alcohol and other sedatives, transparency, and being responsible.

Both parents and the school have to work in mutual co-operation to enhance the educational experience of a child and to mould his/her career. In fact, schools encourage parents to be more involved in their children’s activities because the school authorities know that parents’ involvement can bring about great positive changes in the students. That’s the reason schools invite parents to attend various school activities and functions.

Biedinger, N. (2011). The influence of education and home environment on the cognitive outcomes of preschool children in Germany . Web.

Education. (n.d.). Out-of-school influences and academic success-background, parental influence, family economic status, preparing for school, physical and mental health . Web.

Enotes. (2010). How do parents influence children in life? Web.

Jeynes, W. (2011). Parental involvement and academic success . New York: Routledge.

Rich, A. (2000). Beyond the classroom: How parents influence their children’s education . Web.

- Indoor and Outdoor Activities for Toddlers Based on the Light and Shadow Effect

- American High Schools and Colleges

- “Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada” by Eric Strikwerda

- Well-Educated Person and Their Characteristics

- School Uniform and Maintenance of Discipline

- Teaching Philosophy in Early Childhood

- Assessment and Evaluation

- Plan of Assessing Learner Performances

- Changing the Structure of the Class Grading System

- Influence of Cultural Identity the Way Middle School Students Learn

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, November 6). Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development. https://ivypanda.com/essays/parents-influence-on-a-child/

"Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development." IvyPanda , 6 Nov. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/parents-influence-on-a-child/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development'. 6 November.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/parents-influence-on-a-child/.

1. IvyPanda . "Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/parents-influence-on-a-child/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Parents’ Influence on a Child Essay: How Parents Affect Behavior and Development." November 6, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/parents-influence-on-a-child/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Parents Influence on a Child

This essay about the influence of parents on a child examines the multifaceted ways in which parental behavior, values, and the emotional environment within the home shape a child’s development. It discusses the role of modeling in teaching children social conduct and coping mechanisms, the impact of parents in instilling moral and ethical frameworks, and the significance of the emotional climate fostered by parents on a child’s mental health. While recognizing the profound effect parents have on their children, the essay also considers the child’s individual temperament, societal influences, and their own agency as factors in development. It underscores the importance of nurturing, supportive parenting in guiding children towards healthy emotional well-being and social competencies, highlighting parenting as a reflective journey with societal implications.

How it works

The parental sway on a child’s evolution stands as a topic of paramount significance and intricacy, delving into diverse dimensions of psychological, emotive, and societal maturation. From the earliest stages of existence, the parent-child bond lays the groundwork upon which many aspects of the progeny’s forthcoming identity will be forged. This discourse endeavors to delve into the multifaceted functions parents undertake in molding their offspring’s identities, principles, and conduct, acknowledging the gravity of this duty and the myriad manifestations it encompasses.

Central to parental influence is the notion of modeling. Offspring, with their acute perception and absorptive intellects, glean knowledge through observation and emulation. The conduct, attitudes, and emotional reactions exhibited by parents serve as a living repository from which offspring derive their initial teachings. This apprenticeship extends to social interactions, problem-solving abilities, and even stress management strategies. The dictum “actions speak louder than words” assumes profound relevance here; parents’ day-to-day demeanor, from their treatment of others to their regulation of personal emotions, ingrains in offspring what is deemed acceptable and anticipated in communal comportment.

Beyond the overt spectrum of acquired behaviors, parents also shape their offspring through the values and convictions they impart. This inculcation of a child’s moral and ethical scaffold commences in the nuanced interplay of quotidian existence—via the narratives exchanged, the tenets accentuated in decision-making, and the elucidation parents provide behind their edicts and anticipations. Such influences are perhaps most conspicuous in the domains of education, religious convictions, and cultural customs, where parental inclinations and biases can substantially sway a child’s outlook and attitudes toward society and themselves.

Additionally, the affective ambiance parents cultivate within the domicile wields a pivotal sway in steering a child’s mental and emotional well-being. The caliber of attachment, the presence or dearth of supportive and nurturing connections, and the mode by which conflicts are resolved—all contribute to the budding self-regard, resilience, and interpersonal competencies of the progeny. In households where candid communication, emotional warmth, and unwavering support predominate, offspring are likelier to foster a secure self-concept and salubrious interpersonal skills. Conversely, milieus characterized by disregard, censure, or undue pressure can precipitate an array of emotive and behavioral quandaries, underscoring the profound impact of parental emotional accessibility and backing.

However, acknowledging the weight of parental sway does not invalidate the role of inherent disposition, external societal influences, and the offspring’s own volition in shaping their progression. Offspring are not mere recipients of parental influence; they are active participants in their own socialization, infusing their distinct personalities into the dynamic interplay of influences enveloping them. Furthermore, as offspring mature and broaden their communal horizons beyond the family unit, peers, educators, and media outlets increasingly contribute to their evolving self-concept and worldview.

In summation, the parental influence on offspring is both profound and intricate, encompassing the transmission of behaviors, values, and emotive patterns. While parents undoubtedly occupy a foundational role in sculpting their offspring’s development, it is imperative to acknowledge the complexity of this influence, which operates within a broader context of individual attributes and external societal factors. The duty of parenting, therefore, transcends mere provision for a child’s corporeal necessities; it entails nurturing their emotional welfare, exemplifying salubrious behaviors, and guiding them in cultivating a robust and empathetic outlook. Recognizing the gravity of this influence marks the inaugural stride in the conscientious and introspective expedition of parenting, a sojourn that harbors the potential to mold not only the lives of individual offspring but the fabric of society itself.

Cite this page

Parents Influence On A Child. (2024, Apr 14). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/parents-influence-on-a-child/

"Parents Influence On A Child." PapersOwl.com , 14 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/parents-influence-on-a-child/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Parents Influence On A Child . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/parents-influence-on-a-child/ [Accessed: 25 Oct. 2024]

"Parents Influence On A Child." PapersOwl.com, Apr 14, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/parents-influence-on-a-child/

"Parents Influence On A Child," PapersOwl.com , 14-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/parents-influence-on-a-child/. [Accessed: 25-Oct-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Parents Influence On A Child . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/parents-influence-on-a-child/ [Accessed: 25-Oct-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Parental Pressure on Students

by Richard Wike and Juliana Menasce Horowitz

Have American parents become too pushy about their kids’ education? Many experts seem to think so, judging from several new books by journalists and psychologists that bemoan the growing pressure students feel to do well in school. But at least one group of non-experts — the American public — begs to differ. According to a Pew Global Attitudes survey, most Americans think parents are not pushing their children hard enough.

By a ratio of nearly four-to-one, adults in this country say that American parents are placing too little (56%) rather than too much (15%) pressure on students, with the remaining quarter (24%) saying that parents are exerting the right amount of pressure. Parents and non-parents feel roughly the same way about this question, the survey finds. So do Republicans and Democrats, blacks and whites, older adults and younger adults, people with low incomes and those with high incomes, and people with college degrees and those with a just a high school education or less. The only demographic gap in attitudes about this question — and it’s not especially wide — comes on the gender front. More men (62%) than women (51%) say parents aren’t being tough enough.

To find more substantial differences in attitudes about parental pressure on students, one needs to look east. Far East. When the same question was posed in China, India, and Japan about parents in those respective countries, the results were the mirror image of those found in the United States. 1

In these three Asian countries, solid majorities say children are under too much pressure from parents, and very few believe children face too little pressure. The surveys were conducted from March to May, 2006.

Many Asian countries are known for rigorous educational systems that place heavy pressure on students to perform well on high-stakes university entrance exams and in international academic competitions.

In Japan, for example, parents often send their children to private juku , or “cram schools,” where they spend many hours beyond the regular school day supplementing their studies and preparing for college entrance exams. When the Japanese government recently took steps to reduce student workloads, it met with criticism from parents concerned about the country’s drop from first place in 2000 to fourth place in 2003 on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) mathematics literacy test.

Roughly six-in-ten Japanese (59%) say all this pressure is too much, while 30% feel the demands are about right. Only 9% say students need more parental pressure — a figure that stands in stark contrast to the 56% of Americans who feel this way about students here.

In an email exchange, author Alexandra Robbins, whose book, The Overachievers: the Secret Lives of Driven Kids , focuses on the United States but includes a chapter on Asia, noted that “exam fever” is widespread in Asian countries. “In Asia, unlike the U.S., the college you attend can mean the difference between a distinguished professional career or a life of menial labor,” she wrote.

Even so, Robbins’ book is one of several that argues that Americans students are under growing pressure to perform well at school. “I strongly believe,” she says in her email, “that the American public isn’t aware of just how much pressure children are feeling, because many parents don’t necessarily pressure intentionally.”

There’s a debate in education circles about whether this pressure is being felt around the country, or whether it tends to be confined to upper income areas such as Bethesda, Maryland, where Robbins conducted most of her research. Recent studies by the RAND Corporation and the Brookings Institution have found that American students average less than one hour each night on homework, hardly the demanding schedule of an overstressed juku student. And American students generally rank far below their Japanese counterparts on international tests. For example, the U.S. placed 24th out of 29 developed countries on the 2003 PISA math literacy test and 19th on the science literacy test. So perhaps the public is on to something.

- Samples in China and India are disproportionately urban. For more methodological details, see the Pew Global Attitudes report “ America’s Image Slips, But Allies Share U.S. Concerns Over Iran, Hamas: No Global Warming Alarm in the U.S., China ,” June 13, 2006. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

Most Hispanic Americans say increased representation would help attract more young Hispanics to STEM

Most americans back cellphone bans during class, but fewer support all-day restrictions, a look at historically black colleges and universities in the u.s., key facts about public school teachers in the u.s., 5 facts about student loans, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Negative Effects of Parental Stress on Students

- September 29, 2022

Table of Contents

What is parental pressure and why, mental illness, eating disorders, low academic performance, cheating at school, low self-esteem, problems with sleep, injuries, if an athlete.

As a parent, you always want your children to succeed in any area of life. You want what’s best for them; you dream of them getting into the best colleges and universities, mastering every subject, and being at the top of the class.

However, these expectations sometimes go beyond your child’s capabilities. Your expectations become hard to meet, resulting in more pressure from your side and transforming into anxiety for your child.

Parental pressure is the emotional stress parents tend to put on their children and is often related to academic success, cultural and social standards, and other factors.

The leading cause of parental pressure comes out of concern for the welfare of their children and their employment. Another factor is the parent’s past goals they couldn’t achieve; therefore, they try to employ the same dream in their children, leading to confusion for the kid.

The outcome of these actions is, more often than not, unhealthy on a large scale.

What Can Be the Effects of Parental Stress on Students?

Although the pressure is mainly based on good intentions, sometimes parents can go beyond what’s acceptable for students.

As a student, your child will constantly look for your validation. Even a slightly disappointed expression can send them into a bad mental state; they will start questioning their capabilities, slowly leading to fear, anxiety, and other mental illnesses. Now imagine what too much pressure can make them go through.

More specifically, the effects of parental stress on students mainly include:

Students are prone to experiencing mental illnesses due to many factors. The main factor is pressure to succeed in academics. This kind of pressure mainly derives from high parental expectations that pressure students to do well in all subjects and pass all exams with good grades.

The continuous pressure negatively affects students’ psychological and physical health and increases the chances of developing disorders such as depression, sleep deprivation, and eating disorders.

The challenges of academic life alone, the anxiety of socializing, and time management are more than enough for students to have breakdowns. What adds to these challenges is the continuous pressure from parents. These pressures call for new opportunities for students to develop eating disorders.

Instead of focusing on their studies and daily activities, the added pressure takes their focus away, leading to missed meals that can extend to eating disorders if not controlled.

There is a fine line between being a caring parent and taking things too far. Crossing the line will have many consequences for your kid in the future. Your academic pressure will only make them worry.

A student’s academic performance is affected by numerous factors, starting from physical to emotional aspects. When your child, who is also a full-time student, has to deal with all the pressure from all areas of life and is expected to do well, they will likely fall low in academic performance. That comes as a result of them starting to question their abilities and trying to get better but never meeting your expectations.

Academic cheating is caused by parental pressure, teacher pressure, and poor time management. A student who is always working toward meeting your expectations but feels like he is never near will likely turn to cheat, hoping good grades will make you happy.

Fear of failure stops students from taking up new projects or completing the ones at hand. In the hope of getting your validation for bringing home good grades, they will consider or even commit cheating to receive good compliments and rewards.

As academic pressure increases, psychological health declines. When you as a parent are over-involved, excessive control over how your child defines themselves in the world creates few opportunities for the child to self-reflect and have positive thoughts and feelings. As a result, the chances for self-confidence and self-esteem are compromised.

Kids who feel continuous pressure to do well in school might stay up late studying and struggle to get enough sleep. If not supervised, irregular sleep patterns like irregular eating schedules can lead to much more complicated cases such as insomnia.

If you push your kid to participate in sports despite not being well, it will lead to significant damage.

✅ Request information on BAU's programs TODAY!

First Name*

*By submitting this form, you consent to the personal data provided above to be processed, used, and/or retained by Bay Atlantic University and its members, officers, employees, and representatives for communication, promotional, and marketing purposes.

There are cases when, even if you don’t verbally make your kid participate, they will feel emotional pressure and might continue to participate in sports despite injuries. Ignoring pain or returning to a sport before an unhealed injury could lead to permanent damage.

What Can Parents Do to Avoid Pressuring Their Children?

Although well-intentioned, parental pressure is frequently misinterpreted as love and can negatively affect kids. As a parent, fostering an environment where your kid can grow and succeed is crucial. You should identify your child’s abilities and advise them on how to develop their talents.

Some of the steps you can take to avoid pressuring your kid while creating healthy goals for them are as follows:

After an interaction with your kid regarding their academic performance, take a minute to reflect on your behavior. Have you been fair to them? Were your sayings reasonable? If they disagreed with you, how did you react? And is there a way you can find something that would motivate them instead of making them feel less than they are?

Imagine how happy your kid would be if they heard something encouraging after a bad exam or class, instead of feeling guilty for not studying harder. This will push them to do better next time. Your words of encouragement can be a stepping stone for their success.

At any given opportunity, create healthy interactions with your children. Make them feel worthy of academic achievements. Students accumulate a lot of stress just by being students. You can help them by giving them love and motivation.

Constant parental pressure creates defensive attitudes in children. They might develop unhealthy habits, injuries, and mental illnesses and grow into them.

You should be able to identify your child’s abilities and advise them on how to develop their talents. Success is inevitable if you provide your child the necessary support to pursue their goals in whatever profession they choose without creating a fear of failure. Also, they can use some of the ways you can find in our article on how to reduce stress during college.

Bay Atlantic University

Leave a reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You May Also Like

- 5 minute read

How To Communicate With Your College Student

- December 19, 2022

- 6 minute read

6 Useful Tips to Help You Save for Your Child’s Future

- August 23, 2022

- 7 minute read

The Importance of Knowing Your Child’s Learning Style

- December 16, 2022

Act vs Sat: Find Out Which One is Right for You!

Filling out the fafsa: step-by-step guide for parents.

- August 26, 2022

10 Best Ways to Educate and Save Money for Kids

- August 19, 2022

Why Communicative Language Teaching is Crucial Today?

- October 23, 2024

Key Differences Between ELL vs. ESL

What does a business manager do, school principal salary: how much do they make, request information on bau's programs today.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Parental Mental Health & Well-Being

Surgeon General: Parents Are at Wits' End. We Can Do Better. A New York Times Opinion Essay by Dr. Vivek Murthy, U.S. Surgeon General, on the critical need to address parent and caregiver mental health & well-being.

Parents Under Pressure: The U.S. Surgeon General Advisory on the Mental Health and Well-Being of Parents

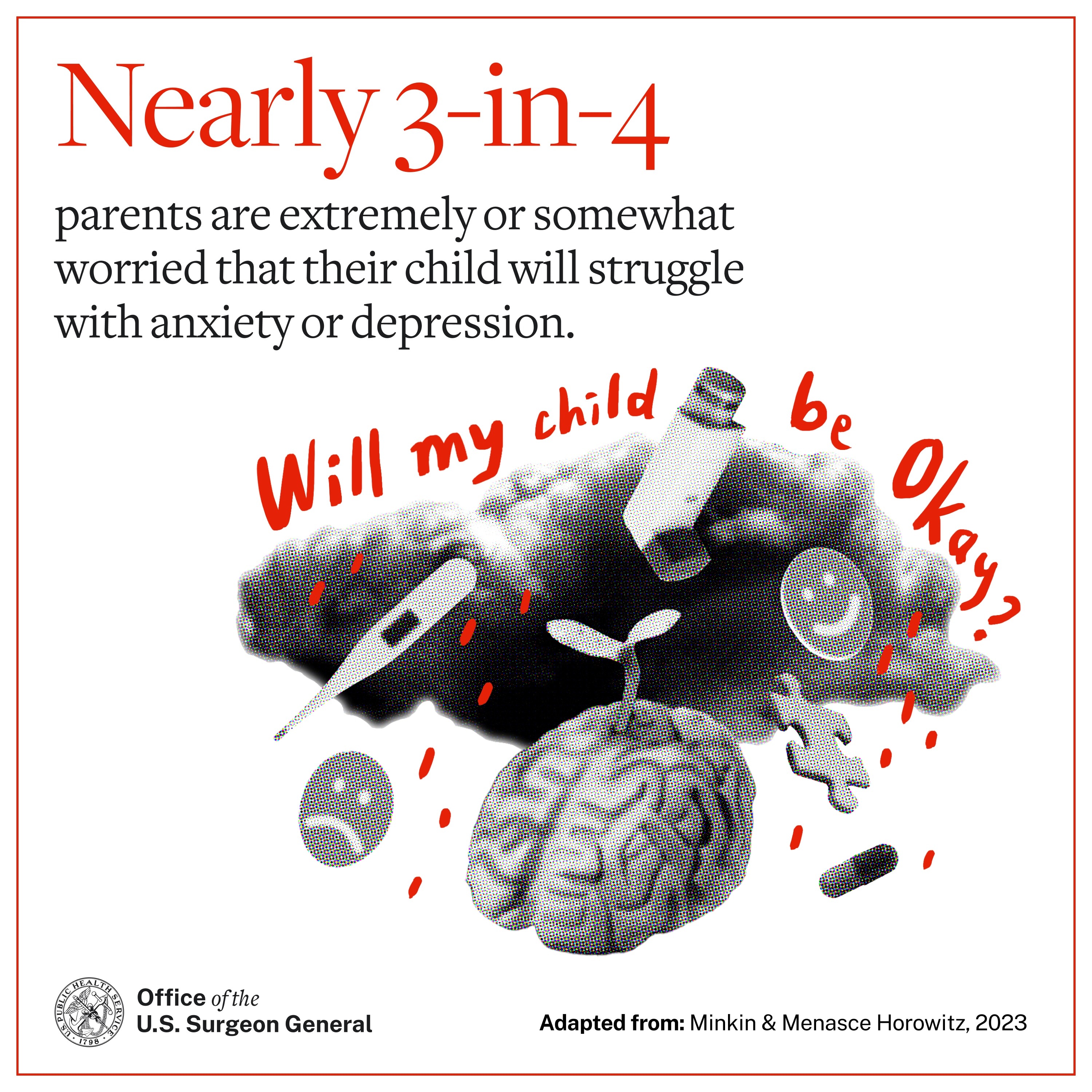

This Surgeon General's Advisory highlights the stressors that impact the mental health and well-being of parents and caregivers, the critical link between parental mental health and children's long-term well-being, and the urgent need to better support parents, caregivers, and families.

Download advisory

Call to Attention: Watch the Surgeon General

Key Takeaways from the Advisory

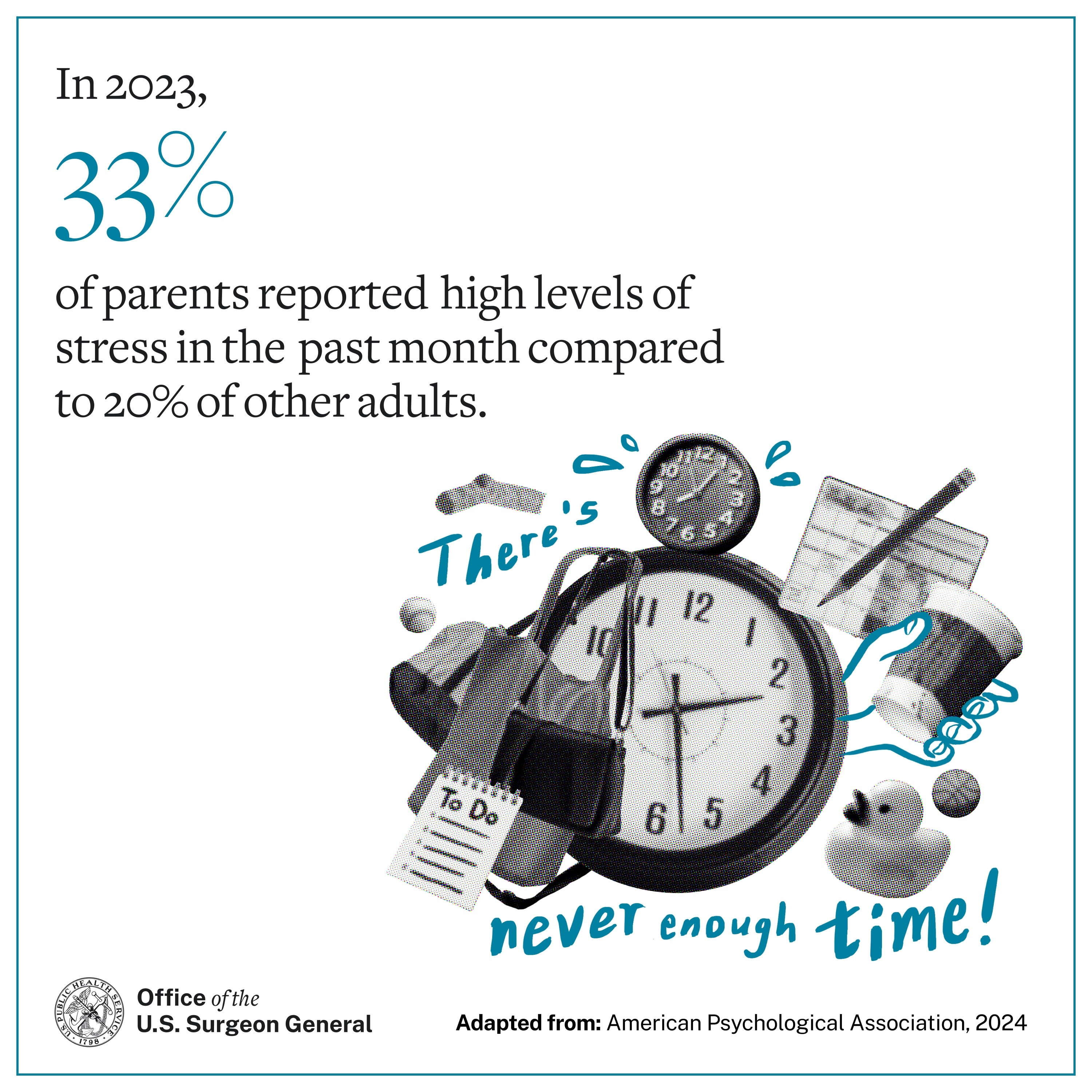

Parents consistently report experiencing high levels of stress compared to other adults

According to 2023 data:

- 33% of parents report high levels of stress in the past month compared to 20% of other adults.

- 48% of parents say that most days their stress is completely overwhelming compared to 26% among other adults.

Parents and caregivers experience a multitude of unique stressors from raising children

These stressors include, but are not limited to:

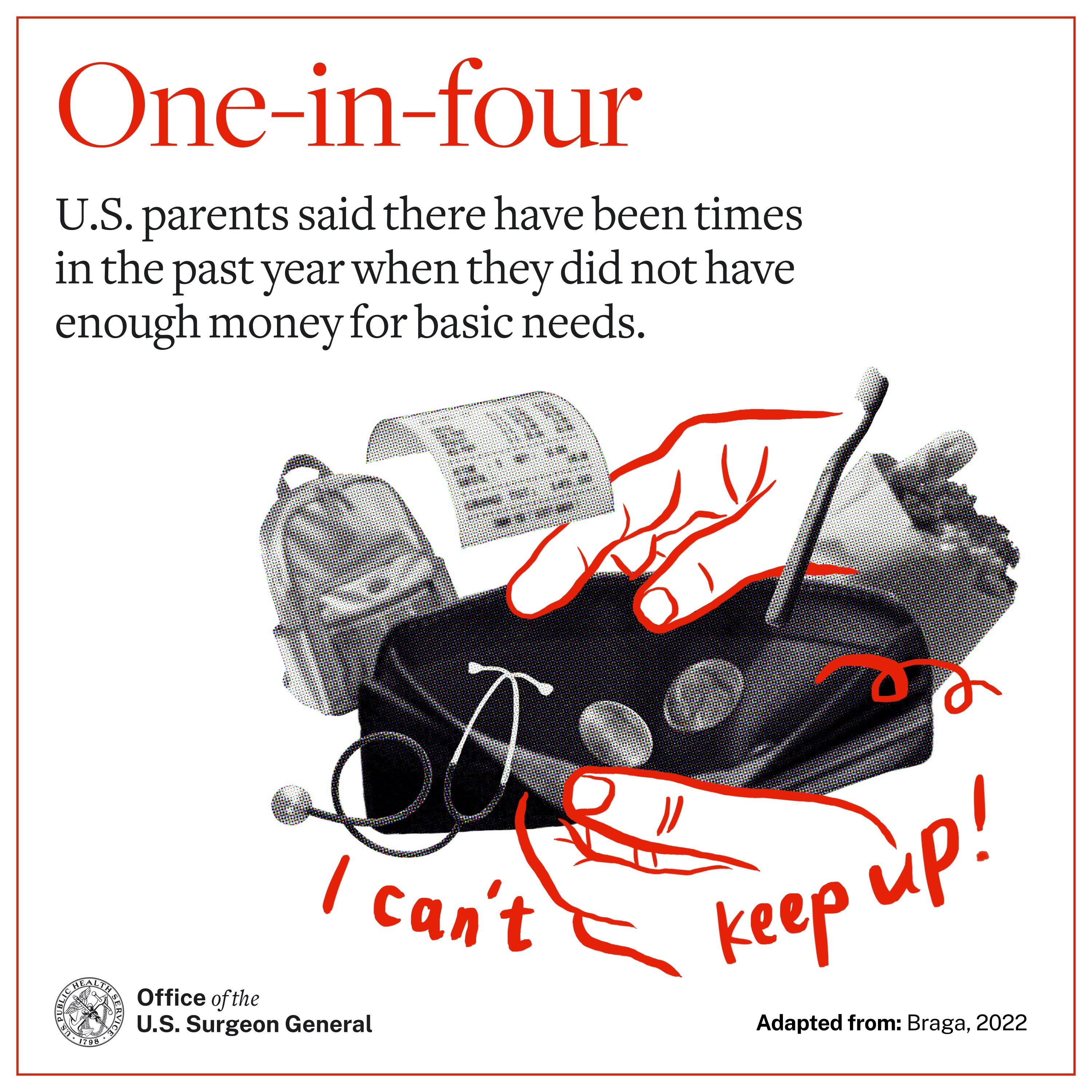

- Financial strain, economic instability, and poverty

- Time demands

- Children’s health

- Children’s safety

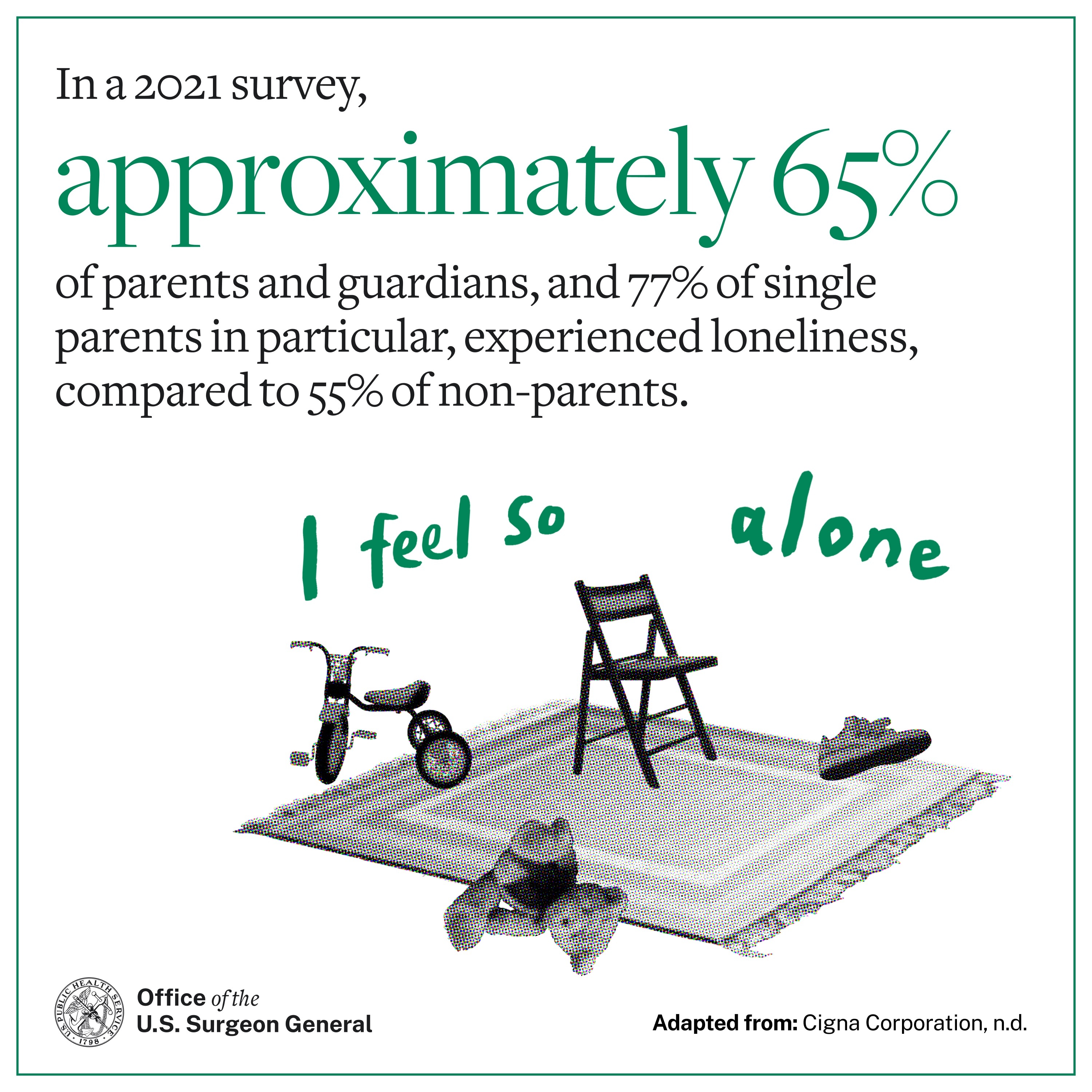

- Parental isolation and loneliness

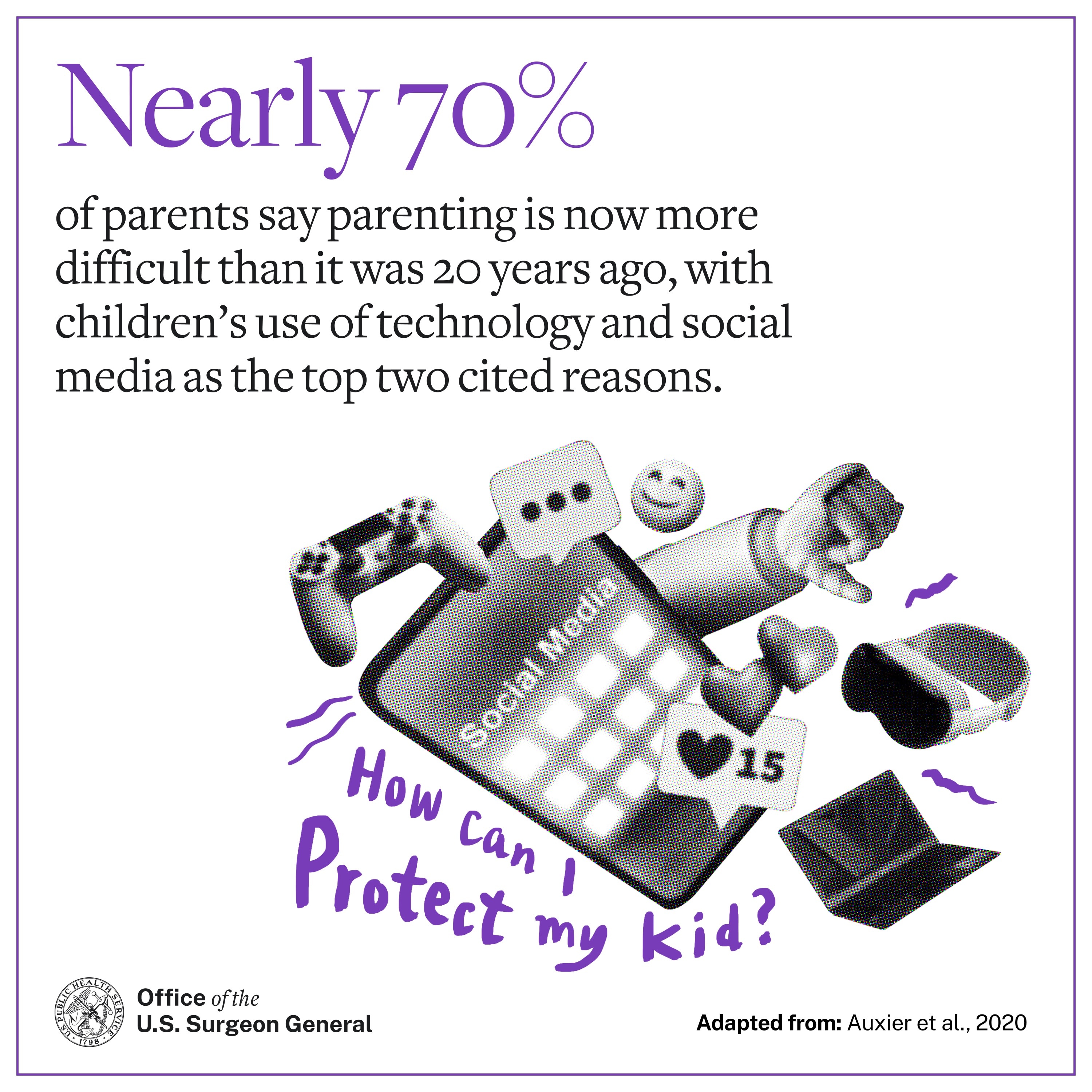

- Technology and social media

- Cultural pressures and children’s futures

Mental health conditions disproportionately affect some parents and caregivers, reflecting broader social determinants of health

Circumstances like family or community violence, poverty and racism and discrimination, among other circumstances, can increase the risk for mental health conditions. Further, the mental health conditions experienced by parents and caregivers can manifest differently based on the gender of the parent and the family structure, among other factors.

We must do more to better support parents and caregivers

The work of parenting is essential not only for the health of children but also for the health of society. Amid a youth mental health crisis, the work of raising a child is just as valuable as the work performed in a paid job and critically important when it comes to the impact on the future of society.

How can we take action?

The well-being of parents and caregivers is a public health priority, and we must do more to protect their mental health. The Advisory offers actionable recommendations on how to support parents and caregivers through policy changes, community programs, and individual actions.

Ways to act based on your role

Policymakers.

- Promote and expand funding for programs that support parents and caregivers and their families.

- Establish a national paid family and medical leave program and ensure all workers have paid sick time.

- Invest in social infrastructure at the local level to bring parents and caregivers together.

- Address the economic and social barriers that contribute to the disproportionate impact of mental health conditions for certain parents and caregivers.

- Ensure parents and caregivers have access to comprehensive and affordable high-quality mental health care.

- Promote visitation initiatives and reentry programming to support currently and formerly incarcerated parents and caregivers, as well as their families.

- Expand policies and programs that support the well-being of parents and caregivers in the workplace.

- Implement training for managers on stress management and work-life harmony.

- Provide access to comprehensive and affordable high-quality mental health care.

Communities, Community Organizations, and Schools

- Foster open dialogue about parental stress, mental health, and well-being in culturally appropriate ways.

- Equip parents and caregivers with resources to address parental stressors and connect to crucial support services.

- Create opportunities to cultivate supportive social connections among parents and caregivers.

- Elevate the voices of parents and caregivers to shape community programs and investments.

- Strengthen and establish school-based support programs.

Health and Social Service Systems and Professionals

- Prioritize preventive care for stress management and mental health.

- Screen parents and caregivers for mental health conditions.

- Foster partnerships with community organizations that provide support and resources for parents and caregivers.

- Provide additional support for parents who are at a higher risk for mental health conditions.

- Support interdisciplinary partnerships between primary care and mental health professionals.

Researchers

- Qualitative analyses, mixed methods research, and community-based participatory research to understand the experiences of parents/caregivers and their mental health challenges.

- Development and evaluation of effective prevention strategies, assessment tools, and interventions that improve mental health outcomes of parents and caregivers.

- Development and evaluation of service delivery strategies for improving access to appropriate mental health interventions and services for parents and caregivers.

- Develop and establish parent-specific standardized measures of mental health and well-being.

- Improve mental health data collection and integration.

- Prioritize research among diverse parent and caregiver populations and family structures.

Family & Friends

- Reach out and offer practical support with household or everyday tasks.

- Connect with parents and caregivers in your life on a regular basis.

- Learn about mental health challenges parents and caregivers may face.

Parents & Caregivers

- Remember, caring for yourself is a key part of how you care for your family.

- Nurture connections with other parents and caregivers.

- Explore opportunities to secure comprehensive insurance coverage for yourself and your family.

- Empower yourself with information about mental health care.

- Recognize how mental health challenges manifest and seek help when needed.

Spread the word with these shareable resources

Meeting Basic Needs Graphic

Download [JPG,1.47 MB]

Parental Loneliness Graphic