- Username Password Remember me Sign in New here ? Join Us

- Ask a Question

Write an argumentative essay on a topic: should female circumsition be abolished give your reason...

Post an answer.

Please don't post or ask to join a "Group" or "Whatsapp Group" as a comment. It will be deleted. To join or start a group, please click here

{{ quote.posted_by.display_name }}

Answers ({{ comment_count }})

Please wait..., modal title, {{ feedback_modal_data.title }}, quick questions.

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

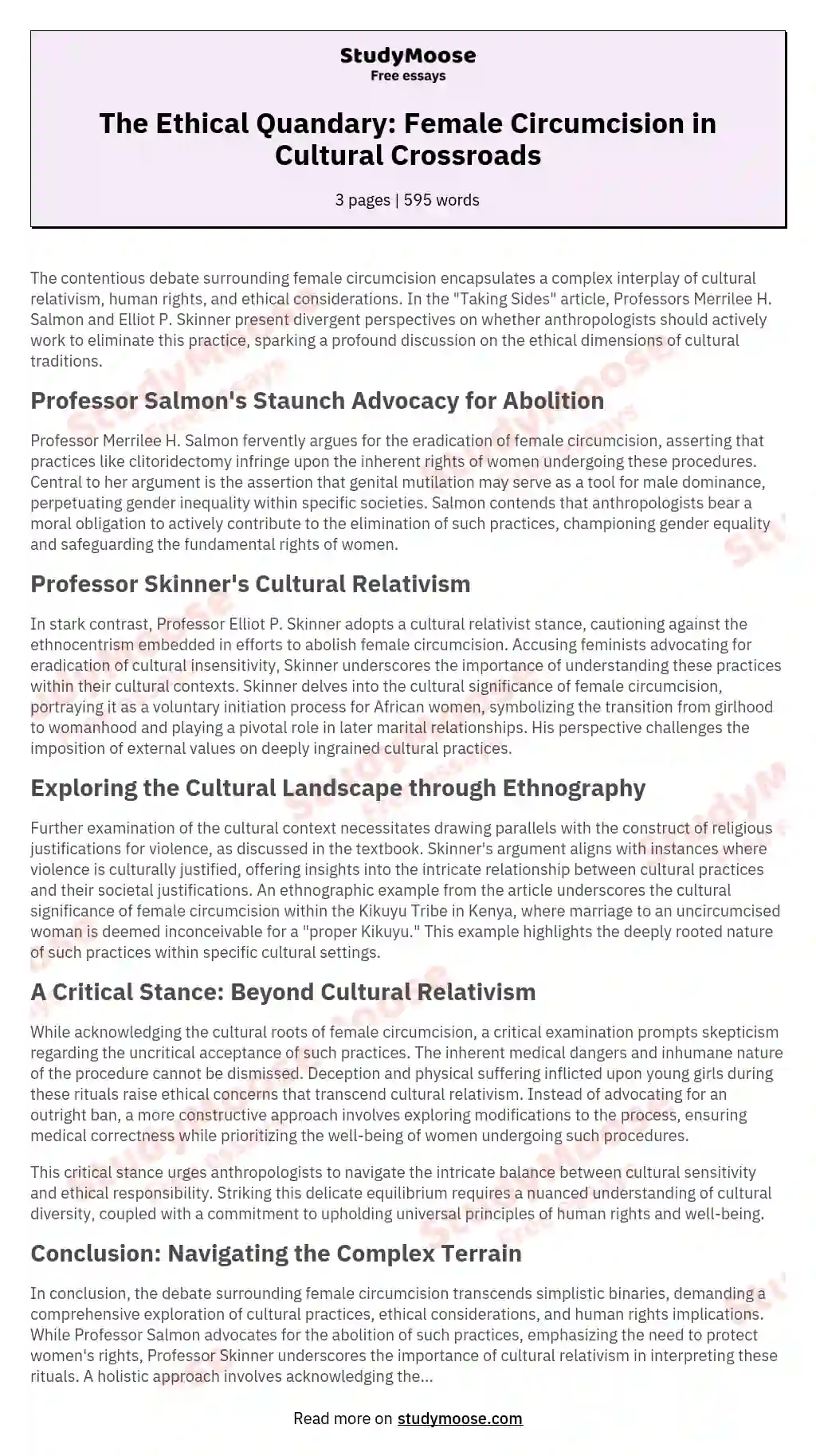

The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Professor Salmon's Staunch Advocacy for Abolition

Professor skinner's cultural relativism.

Exploring the Cultural Landscape through Ethnography

A critical stance: beyond cultural relativism, conclusion: navigating the complex terrain.

The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads. (2016, Sep 14). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/should-female-circumcision-be-banned-essay

"The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads." StudyMoose , 14 Sep 2016, https://studymoose.com/should-female-circumcision-be-banned-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/should-female-circumcision-be-banned-essay [Accessed: 27 Sep. 2024]

"The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads." StudyMoose, Sep 14, 2016. Accessed September 27, 2024. https://studymoose.com/should-female-circumcision-be-banned-essay

"The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads," StudyMoose , 14-Sep-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/should-female-circumcision-be-banned-essay. [Accessed: 27-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). The Ethical Quandary: Female Circumcision in Cultural Crossroads . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/should-female-circumcision-be-banned-essay [Accessed: 27-Sep-2024]

- Wal-Mart Sweatshops: Unraveling the Ethical Quandary Pages: 3 (723 words)

- The Ethical Quandary of 'Plata o Plomo': Navigating Corruption and Coercion Pages: 3 (637 words)

- The Ethical Quandary of Capital Punishment: An Examination of Justice Pages: 4 (1005 words)

- Navigating the Immigration Quandary in America Pages: 13 (3659 words)

- Hamlet's Existential Quandary: To Be or Not To Be? Pages: 2 (532 words)

- World War II: A Diplomatic Quandary Pages: 3 (734 words)

- Horse Racing: Balancing Triumphs, Controversies, Ethical Crossroads Pages: 4 (1191 words)

- Navigating the Ethical Crossroads: Consequentialism and Deontology Pages: 3 (652 words)

- Rukyo's Ethical Crossroads: Justice, Mercy, Truth, and Loyalty Pages: 3 (666 words)

- Unveiling the Digital Tapestry: Navigating Ethical Crossroads in 'The Social Dilemma' Documentary Pages: 2 (576 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

The New York Times

Tierneylab | a new debate on female circumcision, a new debate on female circumcision.

Should African women be allowed to engage in the practice sometimes called female circumcision? Are critics of this practice, who call it female genital mutilation, justified in trying to outlaw it, or are they guilty of ignorance and cultural imperialism?

Those questions will be debated Saturday morning in Washington at the American Anthropological Association’s annual meeting . Representatives of international groups opposed to this procedure will be debating anthropologists with somewhat different views, including African anthropologists who have undergone the procedure themselves. As the organizers of the AAA panel note:

The panel includes for the first time, the critical “third wave” or multicultural feminist perspectives of circumcised African women scholars Wairimu Njambi, a Kenyan, and Fuambai Ahmadu, a Sierra Leonean. Both women hail from cultures where female and male initiation rituals are the norm and have written about their largely positive and contextualized experiences, creating an emergent discursive space for a hitherto “muted group” in global debates about FGC [female genital cutting].

Dr. Ahmadu, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Chicago, was raised in America and then went back to Sierra Leone as an adult to undergo the procedure along with fellow members of the Kono ethnic group. She has argued that the critics of the procedure exaggerate the medical dangers, misunderstand the effect on sexual pleasure, and mistakenly view the removal of parts of the clitoris as a practice that oppresses women. She has lamented that her Westernized “feminist sisters insist on denying us this critical aspect of becoming a woman in accordance with our unique and powerful cultural heritage.” In another essay, she writes:

It is difficult for me — considering the number of ceremonies I have observed, including my own — to accept that what appears to be expressions of joy and ecstatic celebrations of womanhood in actuality disguise hidden experiences of coercion and subjugation. Indeed, I offer that the bulk of Kono women who uphold these rituals do so because they want to — they relish the supernatural powers of their ritual leaders over against men in society, and they embrace the legitimacy of female authority and particularly the authority of their mothers and grandmothers.

You can read more about this in Dr. Ahmadu’s essays or in this critique of the global campaign against female genital mutilation, written by another participant in Saturday’s discussion, Richard Shweder of the University of Chicago.

Dr. Shweder says that many Westerners trying to impose a “zero tolerance” policy don’t realize that these initiation rites are generally controlled not by men but by women who believe it is a cosmetic procedure with aesthetic benefits. He criticizes Americans and Europeans for outlawing it at the same they endorse their own forms of genital modification, like the circumcision of boys or the cosmetic surgery for women called “vaginal rejuvenation.” After surveying studies of female circumcision and comparing the data with the rhetoric about its harmfulness, Dr. Shweder concludes that “‘First World’ feminist issues and political correctness and activism have triumphed over the critical assessment of evidence.”

If I were asked to make a decision about my own daughter, I wouldn’t choose circumcision for her. But what about the question raised by these anthropologists: Should outsiders be telling African women what initiation practices are acceptable?

Comments are no longer being accepted.

When such initiation practices result in the death, mutilation and suffering of thousands of women, then I think yes – we should be telling African women (or anyone else) what is acceptable. Just because it’s part of another culture doesn’t mean we should tolerate mutilation and dubious rituals.

Do you know how female circumcision is actually done? It is not the benign, joyful procedure alluded to by these researchers.

Should African men with AIDS be permitted to have sex with a virgin? Many in Africa believe this cures AIDS, but that hardly makes it right. Cultural imperialism seems an odd phrase to use when discussing female circumcision, a practice that most of the world views as barbaric. I refuse to accept practices such as this, or others such as “honor killings” that are acceptable in certain regions, but should never be accepted in the civilized world.

Anything that puts women at high risk of massive infection, sterility or fistula is ill advised.

The removal of the clitoris cannot be justified by any reasonable ethos.

Adult females should be able to decide for themselves if they want to have their genitals mutilated. People in the West do things like genital piercing and other body modifications that aren’t much different.

What I object to is that young girls might be subjected to it against their will, just as I object to circumcising male babies. A person, male or female, should be able to make that decision for themselves once they are old enough to understand what is going to happen to them.

Before things fell apart in Somalia, the Somali women were engaged in this debate. A pan-African conference was convened by them in Mogadishu which included important Islamic (male) leaders who clarified for them that female circumcision and infibulation was not, rpt not, Koranic. Rather, the cultural origins seem to be Pharaonic, perhaps sharing a timeline with male circumcision as practiced with minor objection even today. The sense of the conference was that, with more medical and cultural information, the practice will find its own end days…without outside pressure.

I am in many ways a believer in cultural relativism, but the reality is that this particular initiation ritual is at best painful but meaningful, and at worst traumatic, crippling and even fatal. Any cultural practice that causes long-term physical or emotional harm to children should be criticized by “outsiders.” For Dr. Schweder to compare female genital mutilation to vaginal rejuvination is absurd- wealthy adult women choosing cosmetic surgery is completely different from young girls being held down against their will to have an important part of their body severed by dirty razorblades and dull knives. There is an important element of choice involved when adults decide to undergo any procedure. For the record, I wouldn’t support American or European women forcing their daughters to have vaginal rejuvination either.

In general, if the practice is one that is done with full consent of all concerned, then it is hard to argue against the doing of such a procedure. The comparison with circumcision is a powerful, and fitting, one.

As to outsiders telling African women (or men) what is acceptable, much of the ‘civilized’ world seems to think it is their right and duty to educate the poor ignorant masses. Evidently, they all need to be dragged to our level of compassionate warfare, backstabbing politics, and ‘laissez-faire morality’. So, no. Outsiders should probably shut their mouths, or at least come to some level of true understanding of the procedure. And then write a book or something.

As to barbaric practices, please. As mentioned, there is circumcision and vaginal rejuvenation along with various breast (and body) augmentations, other vaginal procedures often done for purely cosmetic reasons (e.g., labia augmentation), and a number of other invasive procedures, many having little to do with the individual’s health (the (weak) argument of one’s mental health notwithstanding). And let’s not forget the ‘practice’ of killing innocents in the name of peace and humanitarian aid. Humans are quick to condemn, and far quicker to be hypocrites.

And the last sentence of the blog says much: “If i were asked tomake a decision about my own daughter…”. No one should be making a decision such as this about one’s child, be it FGC or circumcision. Or should they? The debate would be quite interesting.

Mutilation of the female body bathed in cultural relativism is still mutilation, even wtih the anaethesia of brainwashing the victims,

I am glad to read about this subject. I am a white American guy, who has traveled around the world a bit and been to Africa several times (my favorite continent). One of the things I have learned is culture is hard to learn from those who are outside it. Over time, I have come to respect culture even if I don’t “get it.”

I have read and thought about the concept of female circumcision (and like John I have a daughter and would not recommend the procedure to her — but she’s an American girl). The obvious answer to someone of my background is that female circumcision is wrong and perhaps anti-female. Nonetheless (and I am aware that it is generally conducted under female auspices), we American types probably do not fully understand the cultural aspects of this act. So I cannot condemn a procedure where I do not fully (or even partially) understand the background. (I am nominally Jewish and we practice circumcision of our sons when they are eight days old. This is a procedure that many — including myself although my son was ritually circumcised– consider bizarre. Indeed my Jewish wife was against it, and I do not have any compelling reason as to why I wanted it done other than, perhaps, culture.)

The American culture is at best five hundred years old. Yet our culture, admittedly the dominant one today, often attempts to impose its views on all cultures even those thousands of years old. Why does that make sense? Why are we unable to have some minor humility regarding what we know or do not know about different cultures.

One of the wonderful things about life is that there are other cultures. I bemoan the Americanization of the world. The two hour French lunch is gone; fast food places in Paris greatly outnumber the cafes that used to be in the formers’ place. This is not progress, but, of course, we cannot really do anything about it. We can — and I think this is Tierney’s point — simply attempt to be aware of different cultures and also be aware that what seems barbaric at first glance might not be.

With male circumcision as prevalent as it is in our society, and medical reasons no longer a non-religious justification for same, it’s hypocritical for us to call into question another culture’s rituals.

She does have a point regarding our tolerance of male circumcision. Perhaps we should take a look at that.

If degrading female genitals is the only way to express the power of women in Africa, we need to ask why. And probably do something about it. What we should do is beyond me.

Should outsiders be telling African women what initiation practices are acceptable? Not in Africa, they should not, but here in the United States it is, I believe, against the law.

Personally, I feel educated women who defend this practice are irrational. Highly irrational.

You, paleface, would never be asked to circumsize your daughter.

Can the word ‘barbarism’ still have any use in a world ‘contextuarlized’ by anthropology? For me, questions of aesthetics and who is performing the ritual or the claims about hygiene are not what is most important. (If there were real health advantages to such a procedure I suspect it would be more widely practiced) Male circumcision is performed in infancy and the trauma and pain exist in a pre-memory state before the self has been formed. Many still consider it barbaric but it seems to me that consciousness is required for such an ordeal to be described as torture. Hirsi Ali’s description of her own ‘procedure’ undergone when she was a fully cognizant child is almost too harrowing to read. She was pinned down by her (female) relatives and operated on without any anesthesia. I don’t know if it diminishes or enhances sexual pleasure but this seems to be a question for scientists not stewards of tribal ritual.

This article doesn’t mention whether there exists an anti-circumcision movement among female members of the ethnic groups that adhere to this practice. Is there such a movement? If so, what do those women have to say?

It is saying God created us imperfect. We are making an improvement on His creation. This applies both male and female circumcision. Those who believe in circumcision are true unbelievers.

Let’s not be pusillanimous about it or start pussyfooting, female circumcision is inexcusable.

If, as in some instances which have been made public, young females are subjected to the swipe of a crude blade, cutting or tearing labia as well as the clitoris, then these are criminal acts of mutilation, and cannot, morally, be defended by any cultural claim. If, on the other hand, as is implied in the story above, the procedure involves ‘the removal of parts of the clitoris,’ which would have to be a very precise procedure, and no harm is done to urethra or the labia, then it would not be mutilation. But if it has the consequence of reducing, if not eliminating, the sexual pleasure of women, the representatives of the Kona people would have to explain how that could be justified.

If a woman wants to submit to an alteration of her genitals I would think it is her right to do so. Same for a man. Their genitals = their decision. It is when genital alteration is done on some one who does not consent or is unable to consent that I believe we have waded into unethical waters. No one should alter the genitals of some one else because of their own personal preferences. That is highly abusive.

This is not a “new” debate. African women have been discussing these points for more than twenty years. My question is: Why did it take a group of anthropologists so long to discuss female circumciion in a less culturally-biased manner?

I can’t believe such ignorance. Please lets get the facts right. Female mutilation is *not* circumcision. The name says it all, circum-cision means “cut around”, i.e. cut around the extra skin on a man’s penis, which has many health benefits — penis cancer is unknown among circumcised men, plus the penis is allowed to grow more freely without a constricting fold of skin.

This has nothing to do with excising the clitoris, which should be rightfully named Mutilation. This abhorrent practice is often done with a razor blade or even a glass shard, with no anesthetics , a screaming girl held by relatives while the practitioner (an older woman) cuts a large part of her female organ. Bleeding often causes serious infections, sterilty and even death. Try to imagine doing this to your daughter,niece or another little girl you love.

There is no health benefit whatsoever and much less an “aesthetic” benefit as has been claimed. This is sheer oppression of women and cruel abuse of children in the name of “tradition” – the same spurious argument that supported slavery and many other abominable practices that decent people have abolished.

Many FGM practitioners have laid down their instruments and refused to carry on this abomination on the new generation of girls although the practitioners have status in their communities.

Also, many Muslim communities adopt this practice but it is never mentioned in the Koran. (The Koran also never said women must be covered from head to toe, this is just an interpretation of the commandment to be “modest”.)

*** The sole real purpose of female genital mutilation is to prevent women from feeling sexual pleasure. ***

While I believe that everyone should respect the traditions of other cultures, I think there also need to be limitations based on common sense. Two rules come to my mind: Is the practice damaging to the health of the participant in the ritual? Secondly, does the tradition involve cruelty and coercion? In other words, is the participant given a choice, or more or less forced to undergo the ritual? If either of these two situations is the case, then I think outsiders as well as members of the community practicing that tradition have every right to be critical and to come up with “alternatives.” A physician in Florence Italy has come up with an alternative genital ritual for young females of families who insist that their daughters undergo this procedure. The physician’s “ritual” does not permanently damage the young patient’s health but satisfies the needs of the parents and their community. Perhaps this “Third Way” is the approach which should be used.

I don’t think there should be ANY debate! It’s wrong.

Footbinding was also endorsed and performed by mothers on their daughters. That doesn’t mean the practice originated with them. As a nurse, I have personally witnessed and can attest to the medical impact of so called female circumcision: infection, fistula, pain. You can only take cultural relativism so far. I would hope that others who can see more clearly would make critical comments about the foibles of our culture. -Anna

De gustibus non est disputandum.

What's Next

The Complexity of Female Circumcision: Your Thoughts

Many readers were jarred by an Atlantic interview with an anthropologist who tackled a controversial question: What if some women choose to get cut — and even celebrate it?

One of the most provocative pieces on The Atlantic recently came from Olga Khazan, who interviewed anthropologist Bettina Shell-Duncan on the persistent problem of female circumcision in many parts of Africa and the Middle East, despite decades of campaigns led by the United Nations and others. Thousands of you commented via Disqus, Facebook, Twitter, email, and yelling through your screen—"FGM apologist!"—but I tried to compile the most productive points, seen below.

Parsing a reader debate on the best way to end female circumcision—no one is arguing for the practice—is difficult because people are often talking past each other. That difficultly is due to the vast diversity of the 125 million individuals who have gone under the knife; each case is different. Is she an adult, a teenager, or clearly a child? Does she live in a country where the ritual is widespread or a Western nation where it defies all norms? Does she undergo "nicking," excision, infibulation—in which the labia are stitched together—or something in between? Is she forcibly held down, or does she join willingly, even joyfully in some cases?

One such case was described in Olga's interview with Shell-Duncan, who witnessed the ritual cutting of a Rendille woman at her wedding in northern Kenya: "The bride came out [afterwards] and joined the dancing." Olga, though horrified by the practice, emerged from the interview with a more nuanced understanding of how it's performed in various places:

In fact, elderly women [as opposed to men] often do the most to perpetuate the custom. I thought African girls were held down and butchered against their will, but some of them voluntarily and joyfully partake in the ritual. I thought communities would surely abandon the practice once they learned of its negative health consequences. And yet, in Shell-Duncan's experience, most people who practice FGC recognize its costs—they just think the benefits outweigh them.

Here's Shell-Duncan in her own words, prodding people to consider a woman's choice when it comes to circumcision:

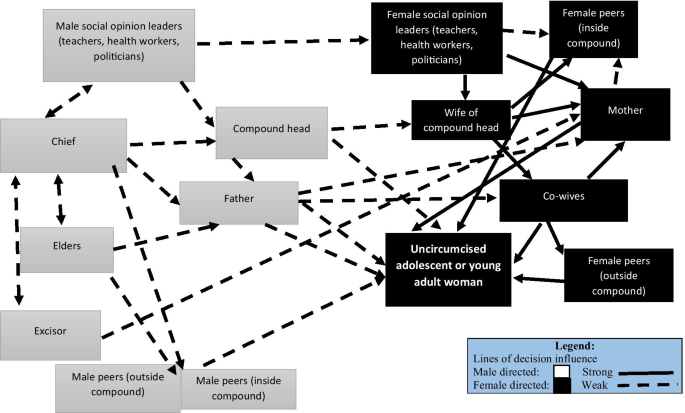

The sort of feminist argument about this is that it’s about the control of women but also of their sexuality and sexual pleasure. But when you talk to people on the ground, you also hear people talking about the idea that it’s women’s business. As in, it’s for women to decide this. If we look at the data across Africa, the support for the practice is stronger among women than among men. So, the patriarchy argument is just not a simple one.

Many upset commenters, including Rosemary Fryth , found the interview rife with "cultural relativism":

We are told that in a multicultural country all cultures have equal value—and thus, all cultural practices as well. Well, it is clear that not all cultures are equal, and pretending that they are allows this sort of inhumane cultural practice to thrive.

Guishe Garra agrees:

The article almost acknowledges female genital mutilation as an OK practice given "their culture." This is a great example of a "liberal" publication flirting with extremely illiberal values in the name of misunderstood "diversity and minority's cultures." If we can't emphatically argue that humanistic values and liberal values are clearly better, we are doomed.

Though to be clear, Shell-Duncan is working with the Population Council to reduce female circumcision "by at least 30 percent across 10 countries over five years"—hardly the goal of someone who "almost acknowledges [FGM] as an OK practice." Arwen McCaffrey puts it well:

The researcher is clearly not in support of the practice. The point of the article isn't to lessen the horror of FGM but rather to contextualize it. Societal pressure to belong is incredibly powerful. This is true in Western cultures as well. Shell-Duncan is remarking how she learned about the many sociocultural factors influencing the practice and that there is no one easy way to end it.

So the core debate should be: What's the most pragmatic, effective way to end the practice? That's difficult to say, since legal prohibitions and health messaging have yielded mixed results so far. One controversial idea from Shell-Duncan is to call it "cutting" rather than "mutilation"—the term officially used by the World Health Organization. But "mutilation," she says, "sounds derogatory and can complicate conversations with those who practice FGC [female genital cutting]." Hilary Burrage isn't buying it:

The wish of leading African women themselves is clearly to refer to the practice as MUTILATION—formally, at least, per the 2005 Bamako Declaration . The United Nations has also recently agreed to refer to this harmful traditional practice only as FG*M*. Please let's hear NO MORE about "FGC." Children's lives and future health are more important than comforting —whether to practitioners or observers —euphemisms. Female genital "cutting" also plays very well to Westerners if they want to evade the cruel truth of how defenceless (undefended) children are being tortured because of "respect" for "tradition."

Maria Alisa , on the other hand, sees the logic of calling it "cutting":

The point of the name change is that if you go in as an outsider and tell people how horrible they are and they have to change a cultural practice, do you think that will work? No. They'll cling to it twice as hard. In our discussions with those cultures over the practice, we must do what works, not what makes us feel smug and self satisfied.

Ilona Geary elaborates on that view:

I n the West, we have the luxury of making decisions based on our own beliefs without our children or ourselves being ostracized or disenfranchised or having their future threatened. We enjoy a certain amount of autonomy that doesn't seem to be present in the people groups discussed here. But when you live in a collective, the traditions that signify a belonging and duty to the group become paramount. I appreciated the article's explanation of the social pressure, especially in a nomadic/small village setting, that drives these mothers and young women to make this decision. In their estimation, it is an important way to secure solidarity and a prosperous future for their child within the circumstances in which they live. I think the practice is definitely dangerous and doesn't have the actual benefits that the people group believe they do, but the only way to change hearts and minds is to continue a respectful dialogue and create OTHER opportunities within these communities. One can't march in with disgust, disdain, and legislation and think this will instantly vanish. Constant communication that provides a connection to a larger world view and more options will eventually turn the tide. Sooner rather than later I hope.

Perhaps "mutilation" and "cutting" are equally useful terms; it just depends on the audience. For anti-FGM activists who want to increase awareness and fundraising in the West, "mutilation" rhetoric is more effective. For anti-FGC anthropologists and health officials who confront the cultural divide on the ground, "cutting" is more effective. Here's how this reader frames the tension at play:

The feminist discourse runs up against the post-colonial one. At which point is it okay to dictate terms to native cultures?

Thop looks to history:

Wikipedia It is without doubt that in the cultures practicing human sacrifice, a significant number of young sacrificial victims (or should I be PC and say "celebrants") participated willingly, even joyfully. In colonial India, the Brits effectively ended—though not totally eradicated—the ancient practice of Sati, the burning alive of the widow on the dead husband's funeral pyre. They started with education and mild restrictions, but with little result. That was dropped for a more heavy-handed ban. But the Brits were all about respecting national customs : General Sir Charles James Napier, the Commander-in-Chief in India from 1859 to 1861 is often noted for a story involving Hindu priests complaining to him about the prohibition of sati by British authorities. "Be it so. This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pile. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. My carpenters shall therefore erect gibbets on which to hang all concerned when the widow is consumed. Let us all act according to national customs."

Another dividing line in the reader debate is the age of the females getting cut. How Liz Deutermann sees it:

I think if a woman wants to be circumcised it should be her choice. What's horrible is when a girl is forced into it.

And girls are clearly the ones suffering the most :

Most often, FGC happens before a girl reaches puberty. Sometimes, however, it is done just before marriage or during a woman’s first pregnancy. In Egypt, about 90 percent of girls are cut between 5 and 14 years old. However, in Yemen, more than 75 percent of girls are cut before they are 2 weeks old. The average age at which a girl undergoes FGC is decreasing in some countries (Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Kenya, and Mali). Researchers think it’s possible that the average age of FGC is getting lower so that it can be more easily hidden from authorities in countries where there may be laws against it.

Which would be a dark irony indeed. But what about adults who undergo FGC? Should it be "their body, their choice"? Sarah White thinks that's a fallacy:

It is not a choice if it is a cultural expectation and one faces ostracism (which means much more in tribal cultures) if one dares to deviate. This is not consent; it is acquiescence. Read Alice Walker's Possessing the Secret of Joy .

Walker also wrote a nonfiction book on FGM, Warrior Marks . Here's a gripping scene from her documentary of the same name:

Even when the participant is an adult, this reader suggests it's still brainwashing:

A lot of people are pointing out that this 16-year-old Rendille girl [witnessed by Shell-Duncan] apparently "chose" to get the procedure done, as if such a thing would have ever occurred to her without getting it drilled into her head since birth that this makes her worthy in the eyes of her community.

Shell-Duncan noted that the Rendille teen "was young by their standards. Mostly they’re 18, 19, 20, around that"—which raises the difficult question of when exactly a minor becomes an adult. When I emailed Hilary Burrage, the aforementioned activist, she had a nuanced take on the consent question:

Regarding the "adults can choose" issue, yes, it is more complex. Some might say there’s a grey area between FGM and female genital "cosmetic" surgery (FGCS), but in reality (regardless of my views on FGCS), I don’t think there is a grey area. FGCS does not remove physiological functions—everything from normal secretions and dampness to obstruction in childbirth—nor does it remove sexual feelings and sensations. FGM often does interfere with function to one degree or another. We have to be careful that those who claim they want FGM as adults don’t also get it done on minors. One example is this interview with an woman who grew up in the US but returned to Sierra Leone to undergo FGM—but submitted her eight-year-old sister to one as well.

Burrage was upset over Olga's piece:

It is a matter of serious regret (and hurt to survivors) that Melinda Gates commended the Shell-Duncan interview on Twitter: I disagree with the practice, but this article has great insight on understanding different cultures: http://t.co/NodZhzRDpF via @olgakhazan — Melinda Gates (@melindagates) April 15, 2015

The Gates Foundation has undertaken excellent work (e.g. maternal malaria), so the praise for Shell-Duncan's analysis contrasts very poorly with this positive contribution to women’s health. Ms Gates should be strongly encouraged to reconsider her position in the light of the evidence cited in my email and elsewhere. You will I’m sure be aware that the UK Royal Colleges (which also produced our national guidelines on issues around FGM) have produced a strong statement explaining why they found the article unacceptable; and I imagine you may have seen my own post written shortly before then.

I am sure The Atlantic (and, perhaps separately, Ms Gates) will wish as a matter of urgency to make it crystal clear that any position on FGM—a totally illegal practice unanimously condemned by the UN—which falls short of outright denunciation is, in one word, unacceptable.

Olga's response:

The problem here is that the communities where FGC/M occurs are all very different. There are many in which girls are coerced and even tortured. There are some, as Shell-Duncan describes, where the practice is seemingly celebrated. I've always been interested in why so many female elders support this practice. How do you go about ending FGM in those societies? Shell-Duncan's description of the girl who was proud to have the procedure done on her was certainly fascinating, but it was by no means descriptive of all women who undergo FGM. However, it does reflect a need for a different type of approach to ending FGM in these areas, and that's what Shell-Duncan provided. Also, I reject the notion that there are "acceptable" and "unacceptable" ideas, as Burrage describes, when it comes to attempting to end a problem as entrenched as FGM. Shell-Duncan was offering one potential solution for a certain type of community; surely there are other solutions that are more applicable to other situations. We all have the same goal in the end.

Our final reader is Soraya Miré, a Somali woman who penned a memoir about her own experience with FGM, The Girl With Three Legs. Here's Soraya 's response from the comments section:

The article failed to understand why our mothers and grandmothers put our bodies through the mutilating ritual and watch us become nothing more than the pleasurable commodity of men. What happened to these women? What about their deep wound, private pain? Didn’t they become wives and mothers, knowing the unthinkable pain? Why then continue the circle of pain? I didn't own a clean razor but felt the prick of the sharp needle as rough hands plucked at my lips like a giraffe feasting on thorny branches. The doctor who was performing my mutilation turned to my mother and said,"Would you like to look at it?" She did and said, "Perfect. Just perfect!" That high praise was meant for my future husband who would find me desirable. I said this many times, that ending the abuse of girls and women is seen as a threat to manhood and a man’s psyche. The article failed to understand the one holding the social and cultural identity mirror. What is the purpose of holding this mirror? And when a young girl looks into that mirror finds a message that reads, “You were born into a female body which automatically labeled you a defected human being in need of reconstruction.” I would love to speak to Bettina Shell-Duncan and offer her education about the cultural mindset of society that views women like chicken without heads. Those of us who survived the horror of Female Genital Mutilation are left with an option to either go along with the cultural torture and abuse or detach ourselves from our roots, our culture and even our family. Reading this article brought back the nightmares about needles biting into my skin and envisioning myself landing on the field of thorns, cut glass, and bloody scissors.

Another Somali-born woman who suffered from FGM, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, touched on the issue in yesterday's Atlantic piece on honor killings in the U.S.:

In the United States, more than half a million women are estimated either to have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM) or to be at risk of it. This number marks a sharp rise in the prevalence of FGM in the U.S. compared to just over just a decade ago. The reason for the increase, according to the Population Reference Bureau, is the rise in the number of immigrants from countries where FGM is common. Those trends show no [sign] of abating.

That trend was the subject of an Atlantic Monthly cover story back in October 1995, "Female Circumcision Comes to America," just at Congress was finally passing a law against FGM. Linda Burstyn's essay opens with an Ethiopian immigrant mother, Genat, frightened that her own mother will circumcise Genat's newborn girl:

"Mother says she will do it anyway, herself—when I'm out of the house—if I don't agree to get it done soon," Genat confides to the woman she hopes will help her. "She says she will take a razor blade and do it." [FGM activist Mimi] Ramsey nods. She has heard this story many times before, and responds by reciting a long list of reasons why the older woman must be stopped, trying to give Genat the courage to buck tradition and disobey her mother. "You cannot let her do this to your child. Please. It is wrong. You know how painful it is. How damaging. Your daughter may hate you for life for what you allow to happen to her." Genat shakes her head. She doesn't want her baby girl, just born in this country, to be circumcised, as is customary in her native land, but her mother is adamant. "She believes in it so strongly," Genat says. "She said if I don't do these things, the girl will grow up horny. She'll be like American girls."

Readers at the time reacted to Burstyn's piece here . Thanks to all the readers this month who commented on the Shell-Duncan interview. We're thinking of posting a similar follow-up on the male circumcision vs FGM debate that also raged in the comments section . If you'd like to offer your take on the subject, email [email protected] and you'll have a much better chance of seeing it posted.

About the Author

More Stories

The Surprising Revolt at the Most Liberal College in the Country

‘Trump Hasn't Been the Wrecking Ball I Anticipated’

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Envisioning an End to FGM/C

Stephanie Desmon

Female genital mutilation or cutting—in which all or part of a girl’s or woman’s genitalia is altered or removed for nonmedical purposes—has been a traditional practice in many countries for over a millennium. More than 200 million women and girls alive today are FGM/C survivors.

In 2012, the UN General Assembly designated February 6 the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation . Guided by Sustainable Development Goal 5 , the UN aims for the elimination of the practice by 2030.

In this Q&A, adapted from the February 5 episode of Public Health On Call , Michele Decker , ScD, MPH, Bloomberg Professor of American Health in Population, Family and Reproductive Health , and Nicole Warren , PhD, MPH ’99, MSN, associate professor in the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, explain the importance of challenging long-standing cultural norms to end FGM/C, and the need to provide appropriate care for those who have experienced the practice.

They also discuss the launch of Johns Hopkins Center for Global Women’s Health and Gender Equity and some of its priority areas, including eliminating FGM/C.

Tell me about the Center for Global Women’s Health and Gender Equity. How did it come about, and why?

Michele Decker: We’re in a watershed moment for global women’s health and women’s rights. We see that in the Sustainable Development Goals. We see it in the inaugural U.S. National Plan to End Gender-Based Violence , the White House Gender Policy Council , and a number of other domestic and global policy initiatives that are elevating gender equity and women’s health.

The Center formed in October 2023 with the mission to advance global women’s health and gender equity through a combination of action-oriented research, training, and translation. We have an incredible wealth of gender equity and global women’s health research underway at Johns Hopkins. This new center allows us to synergize that expertise.

A couple of our priority areas are around eliminating gender-based violence and other harmful practices, including child marriage and female genital mutilation, as well as empowering women and girls and strengthening health systems to optimize gender equity.

Is this an international center? Or does it also have domestic components?

MD: We’ve got people working around the world, including in the U.S. We have gender equity issues right here in our backyard, like the gender wage pay gap and differential jobs and opportunities based on gender. And gender-based violence continues to be a leading driver of women’s morbidity and mortality, and it’s taking way too many people. We also have some U.S.-based work on FGM, or female genital mutilation or cutting.

We’re ready with the evidence base, and we’re ready for evidence-informed change.

Nicole, as an expert on FGM, can you tell us a little about that practice?

Nicole Warren: FGM is the acronym for “female genital mutilation.” That is the term the WHO and many other agencies use. It is a traditional practice that does not have any medical advantages, and that essentially harms some part of the female genitalia.

Is there a difference between FGM and FGC?

NW: As a nurse midwife, I tend to use the term “female genital cutting” because I want to use language that will be acceptable to my clients. Some people I care for absolutely do feel mutilated, and I use that term, FGM, if that’s what they’re using. Otherwise, I tend to use the term FGC, because I try to avoid creating that victim-perpetrator dynamic that just isn’t consistent with how some affected communities view the result of the procedure.

What is the traditional rationale for FGM/C?

NW: Communities would have many different answers, a lot of the rationales boil down to control—controlling behavior, minimizing the potential for promiscuity, and keeping people modest. It’s really about diminishing the potential for a girl or a woman to behave inappropriately. For many communities, FGC is also a way to ensure that she will be marriageable. And in some communities, marriage is what allows survival. So the impetus for families to continue the practice is really powerful.

I want to be clear that FGM/C is not required by any religion. In many countries, you see people of all faiths who practice FGC—Christians, Muslims, and those who follow traditional religions. It crosses financial, religious, and socio-cultural boundaries. Ministers of health do it just as folks who would be considered disenfranchised and poor.

Is this something that can be prevented through behavior change work?

MD: Absolutely—but not just at the individual level. These controlling norms have disproportionate and gendered harm, and we need to address those at the community normative level. We won’t get to prevention at the individual level alone.

NW: It’s really hard for an individual in a community to decide not to participate in the practice because social acceptability is a big driver. The sense of, “this is how female external anatomy looks most beautiful, looks most proper” means there’s a lot of demand for it from men and women.

There are also a lot of people who want to see the practice end, but right now, they’re still getting the cutting done because that risk-benefit ratio hasn’t quite tilted far enough. It is happening, but much more slowly than we’d like to see.

Could laws against FGM/C help?

NW: Well, some countries have laws and some don’t. Even in many countries where it’s illegal, there’s no enforcement. I have worked in Mali for quite some time, and they do not have a law on the books because there is a fear that it will drive the practice underground and make an unsafe practice even more unsafe.

MD: The limitations of criminalizing a behavior like this are a common thread across all forms of gender-based violence. It’s really important to have laws on the books, but it’s not a potent deterrent. We’ve got to think about the normative environment and address those social norms. We can’t just criminalize our way out of it.

You mentioned earlier that there’s a U.S. component to this.

NW: Where the U.S. gets involved is when women migrate here from countries where FGM/C is normative.

After people are affected by the practice, there’s a whole range of sequelae—medical, psychological, sexual, the list goes on. When people migrate to a place where FGC is not normative, they face health care systems and providers that don’t understand how their body is different and sometimes don’t even know the therapies available to treat those sequelae.

In the U.S., we have over half a million women and girls who are potentially affected by this practice, yet we have no consistent training for health care providers on the topic. We see higher C-section rates, for example, and other indicators of poor outcomes, and we can solve that. We can reduce the risks people face after they’ve been cut.

And when we can reduce that risk, develop a good rapport, and provide good care, now we hopefully have a trusting relationship to start talking about prevention. We can start talking about, “What are your plans for your daughter after you have this baby?” We can start thinking about making sure that primary prevention—preventing the first cut—also happens in the U.S.

Stephanie Desmon is the co-host of the Public Health On Call podcast. She is the director of public relations and communications for the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs , the largest center at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Johns Hopkins Launches Center for Global Women’s Health and Gender Equity

- Advancing Reproductive Justice for All

- SEE Change: Improving Health Through Self-Empowerment

Related Content

Anesthesia without capnography: ‘like flying blind’, community vs. coal: reclaiming health in curtis bay, cancer care inequities are costing kids their lives, study estimates home blood pressure devices don’t fit properly for more than 17 million u.s. adults, new research sheds light on treatment and harm reduction gaps among drug users.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Reconciling female genital circumcision with universal human rights

- PMID: 28922561

- DOI: 10.1111/dewb.12173

One of the most challenging issues in cross-cultural bioethics concerns the long-standing socio-cultural practice of female genital circumcision (FGC), which is prevalent in many African countries and the Middle East as well as in some Asian and Western countries. It is commonly assumed that FGC, in all its versions, constitutes a gross violation of the universal human rights of health, physical integrity, and individual autonomy and hence should be abolished. This article, however, suggests a mediating approach according to which one form of FGC, the removal of the clitoris foreskin, can be made compatible with the high demands of universal human rights. The argument presupposes the idea that human rights are not absolutist by nature but can be framed in a meaningful, culturally sensitive way. It proposes important limiting conditions that must be met for the practice of FGC to be considered in accordance with the human rights agenda.

Keywords: cross-cultural bioethics; cultural sensitivity; female genital circumcision; human rights; moral relativism.

© 2017 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Between Moral Relativism and Moral Hypocrisy: Reframing the Debate on "FGM". Earp BD. Earp BD. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2016 Jun;26(2):105-44. doi: 10.1353/ken.2016.0009. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2016. PMID: 27477191

- Reconciling international human rights and cultural relativism: the case of female circumcision. James SA. James SA. Bioethics. 1994 Jan;8(1):1-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.1994.tb00239.x. Bioethics. 1994. PMID: 11657373

- Female Genital Cutting (FGC) and the ethics of care: community engagement and cultural sensitivity at the interface of migration experiences. Vissandjée B, Denetto S, Migliardi P, Proctor J. Vissandjée B, et al. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014 Apr 24;14:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-14-13. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2014. PMID: 24758156 Free PMC article.

- Nurses and requests for female genital mutilation: cultural rights versus human rights. Sala R, Manara D. Sala R, et al. Nurs Ethics. 2001 May;8(3):247-58. doi: 10.1177/096973300100800309. Nurs Ethics. 2001. PMID: 16010918 Review.

- Judging the other. Responding to traditional female genital surgeries. Lane SD, Rubinstein RA. Lane SD, et al. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996 May-Jun;26(3):31-40. Hastings Cent Rep. 1996. PMID: 8736673 Review.

- Pediatric Trauma Care in Low Resource Settings: Challenges, Opportunities, and Solutions. Kiragu AW, Dunlop SJ, Mwarumba N, Gidado S, Adesina A, Mwachiro M, Gbadero DA, Slusher TM. Kiragu AW, et al. Front Pediatr. 2018 Jun 4;6:155. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00155. eCollection 2018. Front Pediatr. 2018. PMID: 29915778 Free PMC article. Review.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources, other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About Oxford Journal of Law and Religion

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. precedent, 3. culture/religion, 4. health/medicine, 5. better reasons, 6. conclusions.

- < Previous

Why Family Law Treats Female Genital Mutilation and Circumcision Differently: An Explanation

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nick Brown, Why Family Law Treats Female Genital Mutilation and Circumcision Differently: An Explanation, Oxford Journal of Law and Religion , Volume 12, Issue 1, February 2023, Pages 96–120, https://doi.org/10.1093/ojlr/rwad012

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Family law in England and Wales draws a fundamental and categoric distinction between female genital mutilation (FGM) and male circumcision (circumcision). The former is a criminal abuse of human rights which, for the purposes of section 31 of the Children Act 1989, can never fall within the ambit of reasonable parenting. The latter is, in principle, reasonable and is therefore not in itself a basis upon which the state can seek to intervene in family life. 1 It will be argued that the reasons given for this distinction in the authorities to date (reasons based on precedent, culture/religion and health/medical issues) are problematic and are not ultimately capable of explaining the distinction satisfactorily. Nevertheless, it will be further argued that a distinction can be properly justified but only when we consider some core underlying features of family law in our contemporary democratic society and that it is only with those features in mind that the different treatment can be explained and viewed as acceptable.

On 14 January 2015, Sir James Munby P handed down judgment in the leading case of Re B (Children) (Care Proceedings) . 2 The case focused on an allegation, pursued by a local authority within care proceedings, 3 that two Muslim parents had subjected their daughter to a form of female genital mutilation (FGM). Having heard expert evidence (of extremely varying quality), the court concluded that it could not make the key finding sought. Nevertheless, ‘given its obvious importance’, 4 Sir James Munby P went on to consider the groundbreaking point—on which he had heard the argument—as to whether FGM amounts to ‘significant harm’ for the purposes of section 31 of the Children Act 1989—the threshold/core statutory provision permitting the removal of children from their parents’ care. The answer to that enquiry was that ‘any form of FGM’ constitutes such harm 5 and that, again for the purposes of section 31 of the Children Act 1989, ‘it can never be reasonable parenting to inflict any form of FGM on a child.’ 6

I conclude therefore that although both involve significant harm, there is a very clear distinction in family law between FGM and male circumcision. FGM in any form will suffice to establish ‘threshold’ in accordance with s31 of the Children Act 1989; male circumcision without more will not. 8

It will be argued, that whilst the fundamental conclusion that there is a distinction to be drawn between FGM and circumcision is sustainable, the reasons given for that distinction within Re B and the authorities upon which it relies are problematic. In broad terms, those reasons are as follows: first, precedent-based arguments support the contention that there is a distinction to be drawn; secondly, issues pertaining to culture/religion allow for different treatment; and thirdly, health/medical-based arguments allow for different treatment. Sections 2–4 will address each of these areas in turn with an investigation as to whether such reasons can satisfactorily ground the distinction that family law maintains between FGM and circumcision—with the conclusion being, in each case, that they cannot. Section 5 will then endeavour to set out better reasons for understanding the different treatment and will point to the conclusion that, ultimately, it can be explained only by understanding some core underlying features of family law itself with a particular focus on what it can/cannot achieve—a point which, it will be contended, is linked to societal priorities which are at large beyond the sphere of family law but which nonetheless provide family law with its particular approach to FGM and circumcision.

In terms of contribution to the field, whilst the literature includes examples of challenges to the different treatment of the practices, 9 it is suggested that there is a lack of sustained and detailed consideration of the reasons given for that difference in the specific context of family law and religion— with there being a particular absence of focus on the nature of family law and what that may tell us about the appropriateness or otherwise of the distinction drawn between the practices.

For the contention that there is ‘no equivalence’ between FGM and circumcision, Re B places reliance upon two asylum cases— K v Secretary of State for the Home Department, Fornah v Secretary of State for the Home Department and SS (Malaysia) v Secretary of State for the Home Department 10 —and this reliance ought to be regarded as problematic.

It cannot be compared to other cultural or religious practices, such as female genital mutilation, which involve a far more serious violation of physical integrity of the body and an expression of subservience. 11

The authority for the above proposition is cited as Fornah and so SS (Malaysia) becomes vulnerable for the same reasons that will be explored in respect of that case itself. Further, Re B in fact clashes with SS (Malaysia) because it specifically negatives the analysis that FGM per se represents a greater invasion of bodily integrity than does circumcision with Re B going so far as to determine that some forms of FGM are ‘on any view much less invasive than male circumcision’ 12 —and with both FGM and circumcision constituting significant harm. 13 SS (Malaysia) and Re B are also at odds because the former describes FGM as a religious practice, whereas the latter asserts it is a practice that ‘has no basis in any religion.’ 14 So as Re B actually departs from SS (Malaysia) on these critical points it is hard to see how SS (Malaysia) can help ground the precedent-based argument that Re B deploys to justify the distinction drawn between FGM and circumcision.

(…) within the familiar definition of ‘refugee’ in article IA(2) of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol (…) The only issue in each case is whether the appellant’s well-founded fear is of being persecuted ‘for reasons of … membership of a particular social group.’ 16

Because neither of the linked cases were about circumcision, Fornah references no detailed evidence, argument or analysis concerning the practice. Its direct/specific commentary on circumcision is contained within only three of the judgment’s 122 paragraphs 17 —two of those paragraphs restricting their observations on the topic to a single sentence. 18 What is said about circumcision does not go directly to the ‘only issue in each case’ (ie ‘membership of a particular social group’) and ought, therefore, to be regarded as dicta . 19 Whilst ‘there are obiter dicta and obiter dicta’ Fornah’ s dicta ought to be regarded as falling on the non-binding or non-persuasive ‘passing remark’ side of the equation as opposed to the potentially binding or persuasive ‘considered judgment on a point fully argued’ side—in particular, because the judgment discloses no ‘purifying ordeal of skilled argument’ on the question as to whether circumcision and FGM are comparable practices. 20

Further, Fornah contends for there being no comparison between FGM and circumcision 21 but without any consideration of what drawing a comparison entails. That is a gap given the abundance of authority for the proposition that, when drawing comparisons between X and Y, the attributes of them both which are said to ‘come into the frame’ are a matter of opinion, out-look and value judgment. 22 This consideration is absent within Fornah and so it goes on to exclude from the analysis points of obviously arguable comparison. So, there is a fundamental point of comparison between FGM and circumcision in that both involve the non-consensual removal of children’s genital parts for non-therapeutic reasons and, therefore, a fundamental interference with the right to bodily integrity. 23 Linked to that are the other essential points: both practices involve pain 24 and are irreversible. 25 Both practices are regarded (at least by some communities) as religious obligations 26 and are, in any event, customs intended to mark a life-stage transition and/or an initiation. 27 Both practices can be driven by mutually held expectations as between the sexes that go to marriageability, 28 beliefs in cleanliness, and perceived aesthetics. 29

Like male circumcision, the cutting of girls is an expression of certain deeply held beliefs about the body, human sexuality and individual and social identity (…) the themes the Western world abhors - removing part of the genitals to reduce sexual pleasure, carving children’s bodies to conform to certain social ideals, visiting pain on helpless children - are all fully present in the history of male circumcision. 30

Finally here, as Re B itself states both practices involve significant harm 31 —a highly notable point of comparison from a basic child welfare perspective and also simultaneously from a legal/procedural perspective as the proof of significant harm (or its likelihood) is one of the requirements to be met to establish jurisdiction for state intervention in family life under section 31 of the Children Act 1989.

Moving on, gaining an understanding of both FGM and circumcision is a task that requires the consideration of expert opinion—an essential point recognized in Fornah given the involvement of the expert in the case to assist on the background of FGM in Sierra Leone. However, the judgment does not disclose any detailed consideration of any expert opinion on circumcision. 32 Further, an expert in family proeedings must set out where there is a ‘range of opinion’ 33 and so in this context, a key difficulty with Fornah arises because the case-critical opinion that FGM evidences an inferiority of women in Sierra Leone is simply not an opinion universally held amongst experts within the field and yet there is nothing in Fornah that would let us know that. 34

Fornah’s ‘procedures’ analysis, with its focus on the circumstances in which FGM can be carried out, conflates procedures with their setting. 35 After all, FGM can be carried out hygienically with anaesthetic and circumcision can be carried out unhygienically without anaesthetic. 36 Further, as Re B observes FGM Type Ia, whilst ‘apparently very rare, is physiologically somewhat analogous to male circumcision.’ 37 That acceptance must also bring with it an acceptance that the procedures are comparable given that the purpose and function of the procedures is to change physiology.

That FGM can have severely harmful consequences is beyond argument 38 but circumcision too may have harmful, even fatal, consequences. 39 More fundamentally, it is not clear why the severity of harmful consequences is necessarily helpful when considering the question of reasonableness/acceptability. Repeatedly stabbing somebody in the face with a knife is a far more serious assault than punching somebody once in the face but it does not follow that the punch to the face is reasonable/acceptable conduct, less still that it is in the best interests of the victim. After all, even a de minimis assault is an assault. 40

It follows from the above that any contention that circumcision can or ought to be regarded as an acceptable practice simply because it is less harmful than FGM is a non sequitur and, consequently, unsustainable—as Steinfield says, ‘this isn’t a harm competition.’ 41 In any event, Re B negatives any suggestion that circumcision is a matter demanding little/no concern by concluding it amounts not only to harm but ‘significant harm’ 42 ie harm that is not ‘trivial or unimportant’ 43 but ‘considerable, noteworthy or important.’ 44 Indeed, on the issue of severity (and as already noted), Re B goes so far as to determine that some forms of FGM ‘are on any view much less invasive than male circumcision.’ 45

Finally, on the ‘procedures’ analysis, if circumcision results in a diminution in sexual pleasure due to the removal of sensitive tissue and/or significant negative psychological sequelae (as evidence in the field suggests 46 ) then it can equally be said of circumcision that, as with FGM, its ‘effects last a life time.’ 47 Further, Re B itself accepts that the ‘long-term consequences, whether physical, emotional or psychological’ of certain forms of FGM may be the same or less great than those associated with circumcision. 48

Nor can the context be compared with male circumcision. As the UNICEF Innocenti Digest, Changing a Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (2005) observes: In the case of girls and women, the phenomenon is a manifestation of deep-rooted gender inequality that assigns them an inferior position in society and has profound physical and social consequences. This is not the case for male circumcision, which may help to prevent the transmission of HIV/AIDS. 49

The three contentions that (i) FGM is a ‘manifestation of deep-rooted gender inequality’, (ii) circumcision is not such a manifestation, and (iii) circumcision has been linked to HIV/AIDS prevention are not contentions that, without more, can be said to justify the argument that there is no comparison to be made. For all we have here are the identification of three purported facts that point to a difference but where there is difference there can still be substantial comparison/similarity. More specifically on this UNICEF citation (and as already touched upon) the assertion that FGM is a manifestation of inequality and inferiority finds extensive challenge in the literature as an oversimplification, including in relation to Sierra Leone—the very country under consideration in Fornah . 50 Further, as Möller argues ‘Patriarchal oppression may make an otherwise rights-violating act even worse, but it cannot ground its wrongness.’ 51 In other words, irrespective of the extent to which FGM is an outworking of patriarchal oppression it is a wholly unacceptable practice with any associated intention to subjugate on the grounds of sex/gender being an ‘aggravating factor’ 52 rather than the wrong itself.

Moving on within the UNICEF citation, as with FGM, so too does circumcision have ‘profound physical and social consequences.’ 53 Further, in jurisdictions such as our own where FGM is unlawful and circumcision lawful, circumcision itself becomes a manifestation of ‘deep-rooted gender inequality’ and itself becomes a form of—to borrow Fornah’ s own phrase—‘gender-specific violence.’ 54

On HIV/AIDS, it is of note that, rightly, the UNICEF material cited is in fact equivocal—circumcision ‘may’ help transmission prevention. 55 This is, therefore, not itself a wholly safe basis upon which family law can draw any firm conclusions about the reasonableness or otherwise of circumcision (as will be argued fully in Section 4).

Further again on the specifics of the UNICEF material, it contains a non-sequitur . The purported logic/reasoning of the second sentence (‘This is not the case for male circumcision (…)’) is that the HIV/AIDS point distinguishes circumcision from FGM which has been noted in the first sentence to have a number of characteristics; but the HIV/AIDS point cannot negative the contention that circumcision also shares (or can share) those aforementioned characteristics.

Finally here, it should be noted that the UNICEF material makes merely passing reference to the practice of circumcision touching upon the issue in just three of its introductory sentences in a document running to a total of 54 pages. It cannot be said to be a document that provides any substantive analysis as to the possible comparison of FGM and circumcision. It also falls foul of the analysis that only FGM can be regarded as a grave act which, as already touched upon, is an analysis specifically negatived by Re B. 56

Building on the themes of the UNICEF material, Fornah then introduces the link between FGM and the control of female sexuality 57 but here it must be recognized that circumcision has itself not been a practice untainted by endeavours to contain, constrain, oppress, and attach shame to the experience of sexual pleasure. 58

The contrast with male circumcision is obvious: where performed for ritualistic rather than health reasons, male circumcision may be seen as symbolising the dominance of the male. FGM may ensure a young woman’s acceptance in Sierra Leonean society, but she is accepted on the basis of institutionalised inferiority. 59

The analysis that circumcision concerns the dominance of the male over other males is problematic for two key reasons. First, it is another oversimplification of matters relating to sex, gender and power as evidenced, in particular, by the active support from/involvement of certain women within numerous circumcision traditions/contexts—Antonelli noting, by way of stark example, that ‘Jewish women have died rather than repudiate the practice.’ 60 Secondly, even if there were no oversimplification here, how could this intra-sex domination contribute to the argument that circumcision should be regarded as categorically acceptable/reasonable? Surely any suggestion that the ‘dominance’ of A over B is acceptable/reasonable simply, or even in part, because A and B are both male is a suggestion that is inherently weak and ignores the point that patriarchy can harm boys/men and not just girls/women. 61 It also ignores the fact that Fornah itself rejects any suggestion, certainly in the context of persecution, that a harmful practice is somehow more tolerable if inflicted on an intra-sex basis. 62

Finally on the issue of patriarchy/gender inequality: when transposed into the family law analysis, the issue results in a loss of focus on the paramountcy principle/rights-based arguments. Let us, for a moment, take the patriarchy/gender inequality argument at its very highest. FGM is, in all circumstances, ‘an extreme and very cruel expression of male dominance.’ 63 Let us say that is not, in any way, an oversimplification but how does that actually help the family court determine whether it is reasonable/in accordance with the welfare paramountcy principle to allow for a boy to be circumcised? The argument is leading to another non-sequitur: conduct X is very cruel, in particular conduct X is, for the purposes of asylum law, a very cruel form of persecution; conduct Y is not; therefore conduct Y is reasonable—this notwithstanding the fact that conduct Y could, for the purposes of family law, be any number of unreasonable acts—anything from stubbing out a cigarette on a child’s arm, to making him eat dog food, or to breaking his back in a fit of anger: the examples are limitless. In short, whilst abhorrence of FGM is wholly justified, that abhorrence tells us nothing meaningful about why circumcision is regarded as reasonable.

In Re B another ‘important’ distinction between FGM and circumcision is as follows, ‘FGM has no basis in any religion; male circumcision is often performed for religious reasons.’ 64 This essential proposition is supplemented and contextualized by the observation that ‘large numbers of circumcisions are performed for reasons which (…) are as much to do with social, societal, cultural, customary or conventional reasons as with anything else (…)’ 65 and also by the observation that ‘The fact that it may be a “cultural” practice does not make FGM reasonable.’ 66 Within Re B , therefore, there appears to be a distinction drawn between religion and culture which is then accompanied by the following sub-distinctions: FGM is not religious but cultural (and in any event unreasonable) and circumcision is religious and cultural (and in any event reasonable). These interrelated contentions are problematic for five key reasons.

First, there are issues of definition. If it is to be said that there is a material distinction between culture and religion with purportedly different practices falling into one of these separate categories (or across categories) then consideration would have to be given to issues of definition—to where culture ends and religion starts (and vice versa). Yet Re B is silent on this and takes no account of the complexity of the following interrelated questions: what is ‘culture’, what is ‘religion’, and what is the relationship between ‘culture’ and ‘religion’, in particular in the context of FGM and circumcision? 67

Re B is further open to challenge here because, in overlooking definitional issues, it takes no account of the ‘trend of authority’ towards a more expansive understanding of what ‘religion’ is 68 —an approach that necessarily enhances the prospect of any particular practice being regarded by the law as religious. Moreover, even where we find workable definitions of ‘culture’, it is clear that it can be hard to extract the religious from the cultural 69 with the often-overlapping nature of culture and religion having also been identified in the specific context of FGM. 70

All this points to ‘culture’ as a very broad concept/phenomenon covering an extremely wide range of human activity/conduct some of which may be religious ie ‘religio-cultural activity/conduct’ and some of which may not be ie ‘cultural-only activity/conduct.’ To some extent, Re B’s analysis accounts for the subtleties of these dynamics because it recognizes that circumcision can be both religious and cultural but its analysis is silent on the possibility of similar subtleties being at large in respect of FGM—that being classified, in essence, as a ‘cultural-only’ practice with no consideration being given as to whether that classification may be incomplete/erroneous.

The second, and closely related key reason as to why the contention that FGM ‘has no basis in any religion’ is problematic, is that the assertion reads as a statement of concluded fact and one which is made in a context in which the court had apparently heard or been presented with no expert evidence and/or argument on the point. 71

Third, it is right that there is nothing in the Quran which specifically mandates the practice of FGM but that can equally be said of the Quran and circumcision—but with both practices being referred to in the hadith (reported sayings of the Prophet Muhammed). 72 Quranic silence alone, therefore, does not allow for any credible assertion that a particular practice is unIslamic; nor, because of the hadith , can it necessarily be said that there is no authoritative textual basis for FGM within Islam. For as Esposito and Delong-Bas note, there are hadith which have been understood by some (albeit controversially) to refer to and support FGM in consequence of which: ‘[Islamic] Law schools are divided on whether FGM/FGC is permitted, obligatory, forbidden, or to be left to parental discretion.’ 73

Accordingly, it is not necessary for a belief to be shared by others in order for it to be a religious belief, nor need a specific belief be a mandatory requirement of an established religion for it to qualify as a religious belief. A person could, for example, be part of the mainstream Christian religion but hold additional beliefs which are not widely shared by other Christians, or indeed shared at all by anyone. 74

Another aspect of the scriptural/textual issue is this: if the assertion that FGM ‘has no basis in any religion’ is underpinned by a purported lack of scriptural/textual mandate for FGM then the implication of that is that were there to be such a mandate then there would be a commonality with circumcision (mandated as it is in the Hebrew Bible 75 ) and further, because of that scriptural/textual mandate, there would be a capacity for FGM to be regarded as a reasonable/acceptable practice. However, a key difficulty here, for both practices , is that the law does not recognize any necessary connection between conduct being mandated (or arguably mandated) by scripture and its acceptability. For rightly the law recognizes that just because X is (or is arguably) mandated by scripture it cannot necessarily follow that X is reasonable. 76 Building on that point, it also has to be recognized that the law does not recognize any necessary connection between religion, reasonableness and a child’s best interests—which is to say that just because X is a religious practice cannot necessarily make it a practice that the law can recognize as acceptable. 77

The above analysis cuts to the core of the purported culture/religion distinction between FGM and circumcision for the following fundamental reason: if, ultimately, a religious practice can be properly deemed as unreasonable then it must follow that the religious quality of circumcision cannot, alone, be determinative of the categoric acceptability of the practice.

Fourth, the assertion that FGM ‘has no basis in any religion’ takes no account of the wealth of evidence that, for many people, FGM does have such a basis. That is clear even from material that was before the court in Re B itself—in the form of UNICEF’s Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. 78 According to its foreword, the statistical overview ‘examines the largest ever number of nationally representative surveys from all 29 countries where FGM/C is concentrated, including 17 new surveys undertaken in the last three years.’ 79 It reports that in 4 out of 14 countries (namely Mali, Eritrea, Mauritania, and Guinea) more than 50 per cent of girls/women questioned regarded FGM as a religious requirement. In 2 of the same 14 countries (namely Mauritania and Egypt) more than 50 per cent of boys/men questioned regarded FGM similarly (with 49 per cent of girls/women questioned in Egypt regarding it as a religious requirement). 80 Whilst in other countries the percentages were not as high, they were plainly of statistical relevance pointing to the notable existence of a belief in those countries that FGM is a religious requirement.

there is an important distinction between arguing that a particular Islamic community is incompatible with international human rights or the fundamental ideology of the United Kingdom State, and arguing that it is unIslamic. 82