- Join our newsletter

The Philippines’ Relations with China: A Pragmatic Perspective under President Duterte

T.note n.51 - rise series #12.

The Philippines’ relations with China have recently experienced turbulence, with the occurrence of various controversies and disputes. The issues behind development projects have cast doubts on the integrity of Chinese investments and revealed the venality of Philippine institutions . Moreover, the fiery and contentious maritime row between the two countries has led to the deterioration of bilateral ties. These long-standing hostilities have brought diplomatic relations to their lowest point since they were established in June 1975.

However, with the current administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, bilateral relations have taken a dramatic turn – from a hostile mood to a more amiable outlook. In his state visit to China in October 2016, Duterte declared the Philippines’ “realignment” with China, after five years without any high-level exchanges between the two governments. Departing from his predecessor’s uncompromising stance, Duterte opted to downplay security issues in favour of reviving political relations and pursuing economic ties with China.

During the administration of President Benigno Aquino III (2011–2016), bilateral relations were dominated by maritime disputes. Since 2012, China has seized and taken effective control of Scarborough Shoal, which is situated within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The situation has been further aggravated by unlawful establishment of infrastructures in the area and an illegal ban on Filipino fishermen’s access to its fishing grounds. Bilateral ties took a downturn when the Aquino administration filed an arbitration case against China in 2013, under the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). In 2016, the UN Arbitral Tribunal decided that “ the Philippines has exclusive sovereign rights over the West Philippine Sea (part of the South China Sea) and that China’s ‘nine-dash line” based on its historic rights is invalid ’”.

Given its political and security issues, the Philippines has faced difficulties in its economic relations with China. At the height of the territorial disputes, it faced stricter implementation of trade rules and commercial regulations by Chinese authorities. This was evident when China imposed stringent food and safety standards and requirements in 2012 that led to the ban on banana imports from the Philippines. The ban was enforced after Chinese quarantine officials discovered mealybugs in several containers of bananas shipped to China. The decision was widely seen as China’s reprisal against the Philippines at the height of the disputes in Scarborough Shoal.

However, since assuming the presidency Duterte has adopted a more amiable style of engagement with China. His accommodating approach has been rewarded by various pledges of loans and investments that would fund infrastructure development projects in the Philippines. And most importantly, Filipino fishermen have returned to their normal fishing activities, although still under watch by the Chinese Coast Guard.

This is especially important given the past controversies regarding Chinese-funded projects in the country. The North Rail and National Broadband Network were among the projects in the Philippines that were cancelled due to allegations of corruption and irregularities. Such controversies produced national embarrassment for the Philippines and created a negative image for China. But with the Philippines’ membership in the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and its participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the country is expected to have more constructive economic engagement with China. In fact, China remained the Philippines’ biggest source of imports, with a 20.8 percent share, in January 2017, with payments recorded at $1,552 billion. This reflected an increase of 26.4 percent from $1,228 billion in January 2016. Meanwhile, revenues from the Philippines’ exports to China reached $501.2 million, generating a total bilateral trade value of $2,053 billion. For the Philippines, these active bilateral trade and recent regional developments will benefit its domestic economy while improving diplomatic relations. For China, such initiatives will further elevate its economic influence in the region while neutralizing its image of bellicosity in asserting its maritime claims.

The Philippines also gained positive momentum in renewing political and security ties with China. Despite the favourable arbitration ruling, because of its weak naval capabilities the Philippines cannot enforce its maritime rights and challenge the Chinese Coast Guard barricading in the Scarborough Shoal. It was not until Duterte’s state visit to China that Filipino fishermen were able to return to the area and resume their fishing activities after four years of Chinese prohibition. Moreover, high-level bilateral dialogue regarding maritime disputes has resumed following Duterte’s participation in the BRI Summit in Beijing last May.

The warming up of bilateral ties after years of frosty relations can be attributed to Duterte’s pragmatic policy. Evidently, he departed from the Aquino administration’s defiance against Chinese assertiveness in the West Philippine Sea. And instead, Duterte opted to cooperate with China in managing tensions in the area by not taking any military action after the court’s ruling, while amassing various economic concessions in the process. He considered that focusing more on the trade and economic aspects of the Philippines’ relations with China would ultimately benefit the Filipino people more than insisting on national maritime claims that it cannot impose. This may appear to be a very opportunistic economic tactic, and it may almost seem that the Philippines is forsaking its maritime security; but Duterte’s foreign policy adjustments have a logical basis that reflects his calculating and business-like approach.

Moreover, the Duterte administration highlights an “independent foreign policy” that seeks to move the Philippines away from its dependence on the United States. While the United States is its long-standing ally, the Philippines under Duterte is pushing to deepen relations with other, equally important partners such as Japan. It also seeks to strengthen relations with non-democratic countries that hold divergent political values, such as Russia. Although the Philippines is a long-standing democracy, its increasing interaction with Russia reflects Duterte’s pragmatic foreign policy and accommodating posture, which emphasizes concrete bilateral dealings rather than ideological engagements. The Philippines also strives to steer clear of big power rivalries and seeks to cooperate with various countries that will potentially bring in economic benefits, regardless of any looming political issues.

While the Chinese government has welcomed this positive breakthrough in bilateral relations, public opinion in the Philippines is divided on whether or not this was a sound move by the Duterte administration. But the general perception is that Duterte’s accommodating policy towards China has temporarily de-escalated maritime tensions and enhanced trade ties. As a small power, the Philippines considers this a welcome step towards a more peaceful neighbourhood for its economic development.

In the long term, it is imperative that the Philippines be accommodating yet vigilant in its relations with China under its still-ambiguous, yet-to-be-operationalized “independent foreign policy”. Given the shift in its foreign policy, the challenge for the Philippines under Duterte is to be consistently cautious in its policy implementation. Foreign policy must be supervised by established institutions in order to put a check on decisions based on personal impulses, which have been the trademark of the Duterte administration so far.

Andrea Chloe Wong is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch, New Zealand. She is also a non-resident WSD Handa Fellow of the Pacific Forum CSIS. She previously served as a Senior Foreign Affairs Research Specialist at the Center for International Relations and Strategic Studies of the Foreign Service Institute, Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines. You may reach her at [email protected] .

T.wai Journals

Events & Training Programs

Region europe 2024, tochina summer school 2024, china management & business program 2024, how can t.wai be useful to you.

- TOChina Summer School

- TOAsia Export Training

- CMBP – China Management & Business Program

- Region Europe

Researchers

- OrizzonteCina

- Human Security

- Research & Policy Papers

Professionals & Companies

- TOASEAN Business Days

- TOChina Alumni

- China-Italy Philanthropy Forum

Government & Institutions

Torino World Affairs Institute

Strategic partners.

Copyright © 2024. Torino World Affairs Institute All rights reserved

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Collaborate with us

- Amministrazione Trasparente

- T.wai T&R

The Challenges Facing Philippines–China Joint Development in the South China Sea

Territorial and maritime disputes in the South China Sea have been a major irritant in Philippines–China relations. When Rodrigo Duterte became president in 2016, a policy decision to underscore pragmatism in relations with China and opt for a moderated approach to dispute settlement in the South China Sea became clear. In November 2018, China and the Philippines signed a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in Oil and Gas Development, raising the prospect of an eventual joint development agreement (JDA) in the South China Sea.

It is widely presumed that the area around Reed Bank is being considered for a JDA, although other possibilities include waters off Northwest Palawan, West Balabac, and West Calamian. All would be within the Philippine exclusive economic zone and China’s nine-dash line.

However, things are easier said than done. Media narratives, public opinion, the state of political ties, and nationalist sentiment in both countries are all crucial variables for reaching a JDA. One major political risk for pursuing an agreement with China is the country’s unfavorable image in the Philippines. There are four key reasons why Filipinos mistrust and have negative perceptions of China with respect to the South China Sea: (1) the restriction of Filipino fishing activities by the China Coast Guard; (2) the commission of illegal fishing activities (e.g., destruction of coral reefs and harvesting of endangered species) by Chinese fishers; (3) interceptions of Philippine supply vessels and patrol aircraft; and (4) the reclamation and militarization of maritime features in the Spratlys.

Along with this, Philippine domestic politics and political capital figure in the success (or failure) of Chinese projects in the Philippines. For example, after then-president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo won re-election in 2004, her entire term was hounded by questions of legitimacy due to alleged electoral fraud and corruption. This caused the public and her political foes to be vigilant of her every move. When the Joint Marine Seismic Undertaking (JMSU) with China and Vietnam was signed in 2005, there were widespread protests by political forces antipathetic to Arroyo. Notably, in the wake of the JMSU, Arroyo cancelled the China-funded National Broadband Network-ZTE and Northrail Project due to alleged irregularities and kickbacks. Arroyo arguably did so as damage control while beset by political scandals.

The enduring questions associated with JDAs have always been about which laws apply. The Philippine Constitution and the 2016 arbitral award pose twin legal hurdles in finalizing a JDA with Beijing. For Manila, a JDA is only possible if it is in accordance with Philippine law and grants the government “full control and supervision” as required by the constitution. The conventional wisdom is therefore that the memorandum of understanding signed in 2018 cannot be instituted as a government-to-government agreement and should be in conformity with the existing Philippine Service Contract system wherein foreign partners operate as subcontractors to Philippine corporations. This would undoubtedly be unpalatable for China since it would imply that the Philippines has sovereign rights over Reed Bank. Meanwhile, the arbitral award specifically affirmed that there are no legitimate overlapping claims with China in the areas being considered for joint development. This makes cooperation more difficult than in the period before the ruling.

In this context, clearing the obstacles facing a Sino–Philippine JDA will require a multifaceted approach. The South China Sea is not just a resources issue, but also encompasses environmental, legal, political, and strategic concerns. If only one problem is targeted (e.g. hydrocarbon resources), other issues would remain, creating mistrust and leading to “dysfunctional” cooperation.

It is in this regard that China should endeavor to maintain the status quo and refrain from further reclamation of maritime features and militarization of already occupied man-made islands, as these cause profound uneasiness on the part of smaller claimant states. Similarly, if the finalization of the China-ASEAN Code of Conduct in the South China Sea is prolonged, doubts about Beijing’s intentions and sincerity will amplify. There is also a serious need to improve the strategic communications strategies of both the Chinese and Philippine governments. China has to manage its political messaging for its internal and external audiences: the strong rhetoric that uses for its domestic audience has adverse implications for its relations with neighbors. The Philippines, in order to avoid triggering domestic opposition to a JDA, should desist from making fatalistic statements so that the deal with China will not be perceived as lop-sided or a concession of sovereign rights.

Even more importantly, a JDA will not be possible without proper legal cover. This is the most complex part of the JDA, as a legal framework should not be in violation of Philippine law. This could only be done if there is a bilateral treaty that would serve as legal basis for a JDA. As a time-honored legal maxim goes, “everything which is not forbidden is allowed.” Notably, the treaty needs to address various contentious issues: governing labor laws, tax laws, contract laws, the operating authority, profit-sharing terms, transparency, and the dispute settlement mechanism.

Lastly, since negative perceptions on the South China Sea issues are deeply embedded among the Philippine public, an agreement or mechanism for marine environmental protection in Scarborough Shoal is imperative in order to allay concerns over illegal/destructive fishing practices. Addressing these challenges jointly will create a more conducive environment for a Sino-Philippine JDA.

This piece was adapted from the author’s upcoming chapter in Cooperative Development in the South China Sea: Policies, Obstacles, and Prospects (London and New York: Routledge, 2021) which will be published this month.

Aaron Jed Rabena is Research Fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress in Manila and a member of the Philippine Council for Foreign Relations. His areas of interest include Strategic Studies, East Asian Geopolitics and Multilateral Politics, Political Risk, and Chinese Politics and Foreign Policy.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

Philippine-China Relations, Territorial Disputes, and Threats to ASEAN Stability

Malaysian Journal of International Relations

Related papers

The postwar era has enabled the international community to really depend on soft power in the conduct of relations with each other. The creation of the United Nations, and other international organizations has helped manage and prevent disputes and conflicts that would possibly lead to another world war. States have been able to advance their national interests or positions relevant to international issues and negotiate with other States through diplomacy. The shift from hard power to soft power has brought-on the one hand, the rise of international law and international codes of conduct that became the " great equalizer " of States that manifested the consciousness " right is might " , rather " might is right " ; and on the other hand, has grounded States into a more complex form of relationships, having the victors of the war yielding greater power and dominance in the said institutions-hence, the opportunities and challenges of the new world order. This paper intends to present an example of the double-edged sword aspect of the new world order of the postwar era. It shall reflect on a contemporary international issue, the South China Sea dispute, and try to look into how it has changed the landscape of international affairs in the Philippine perspective. Further, the geopolitics of the Southeast Asian region and its collective aspirations relevant to the issue will be looked into against the success or failure of the exercise of soft power/ diplomacy. However, this essay is only limited into contextualizing the issue and does not intend to formulate recommendations and suggestive actions. All of these shall be done in order to evaluate the present conditions of the postwar Philippines with respect to foreign policies and the promotion of its national interests as a sovereign nation.

Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs

Focusing on the Philippines’ changing foreign policy agendas on the South China Sea dispute, this article examines the limitations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) intergovernmental approach in addressing security challenges in the Indo-Pacific region. It contends that former President Benigno Aquino III tried to harness this regional organisation in his balancing policy vis-à-vis China’s maritime expansion in the South China Sea. On the contrary, President Rodrigo Duterte promoted his appeasement policy on China when he became the ASEAN’s chairperson in 2017, and pushed for the elusive passage of the ASEAN–China Code of Conduct in 2019. In conclusion, the article scrutinises the implications of this shift in the Philippines’ foreign policy for the ASEAN, and raises the need for this regional organisation to rethink its intergovernmental approach to the security challenges posed by the changing geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific region.

Pivot Toward China: A Critical Analysis of the Philippines’ Policy Shift on the South China Sea Disputes, 2019

This article investigates the Philippines’ puzzling reversal of its position against China following its victory in the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) on maritime claims in the South China Sea. Instead of asserting its de jure sovereign rights, which were reaffirmed by the PCA’s decision, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte instead opted to build stronger relations with China. Proposing a burden-sharing analytical approach, the article argues that the Philippines is using China as leverage in its alliance with the United States. By exploiting the “China Card” and downplaying the arbitration case, the Philippines has extracted concessions from Beijing and Washington. In capitalizing on the Sino-American rivalry, Manila has reaffirmed its strategic value within the U.S.‒Philippines alliance while benefitting more visibly from Chinese foreign aid and investment pledges. However, the Philippines’ policy posture vis-à-vis China reflects short-term diplomatic and economic tactics rather than an enduring strategic reorientation away from the United States.

The intensification of territorial and maritime disputes between the Philippines and China has become the focus of regional and international attention. These disputes have adversely affected the state of bilateral relations, which have deteriorated to a record low level since the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1975. There is growing concern as to whether these disputes can be resolved peacefully or whether they will intensify further and lead to a diplomatic rupture or even a military conflict (2015).

Przegląd Strategiczny

The South China Sea is the most inflammable area in the region of Southeast Asia due to its natural resources, commercial and political importance. The ASEAN countries directly involved in the dispute have conflicting interests, mainly related to their relationship with China, a pretender for the whole area. Therefore, attemps to settle the dispute are not successful. On July 12, 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague issued a verdict taking into account the Law of the Sea, in which it accepted the Philippines’s arguments and rejected China’s claims based on historical arguments against the islands in the South China Sea. China did not take part in the trial and found its sentences non-binding but at the same time it has entered into a dialogue with ASEAN on the code of conduct (COC) in the South China Sea. The purpose of the article is to discuss how the parties are involved in the conflict, progress towards signing the Code of Conduct for the Parties in the South Ch...

Occasional Paper , 2018

Hamstrung by its de facto unanimity-based decision-making process, the ASEAN has failed to forge robust resistance to aggression of extrnal powers, especiallly China’s in the South China Sea. Moreover, strategic acqueincene of key countries, especially the Philippines under Beijing-friendly President Rodrigo Dutetre, has further weakened the ASEAN’s hand, risking the prospect of ASEAN peripepherality, rather than centrality, in shaping the security arhcitecture. Nonetheless, resistance by and minilateral cooperation among three key Southeast Asian powers of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, the current ASEAN chair, portends increasing resistance to, albiet in a divided fashion, to Chinese revanchist ambiitons in the South China Sea. Moving forward, however, the ASEAN should contempltate fundamental institutional reforms and pro-actively foster greater internal coherence in order to effectively address the China challenge. What is at stake is not only ASEAN centrality, but also peace and stability in the region.

In 2016 there were several events that could change the Philippines' foreign policy in Southeast Asia. The tensions in the South China Sea were growing since several parties claimed the sea, and there were new presidents elected in the Philippines and the United States. This thesis focuses on the Philippines' strategy in this complicated geopolitical situation between the two great powers, the United States of America and China. The aim of this thesis was to identify how the Philippines respond to the changing geopolitical dynamics in the region after 2016 in the case of the South China Sea and which strategy they are using in their actions. The author explains the situation in the region, defines a small state, and then discusses the potential strategies a small state has in the case. The author set a hypothesis that the Philippines mainly use a hedging strategy to respond to the region's geopolitical dynamics. To test the hypothesis, the author conducted content analys...

Ocean Research Foundation, New Delhi, 2014

American Journal of Chinese Studies, 2016

On January 23, 2013 the Philippines alerted the international communit) that it had initiated a case against China in to help resohe the dispute regarding China's continuing mme into the South China Sea. 'I he body set to hear the case against China is the United '\ations Convention on the Law of the Sea (lJNCLOS). China's re'>pome \\as presented in a scathing 93-point rebuke of the Philippines. China claims that the Philippines has not followed proper channels in ll\ing lo resol\'e territorial disputes, and China remains willing to discuss this al a bilateral level. For their part, Philippine officials claim that China is bullving its \\'a) into hegemonic control of the South China Sea. This paper presents a contexlllal understanding of the current situation with an eye toward history as a way through thb potential geopolitical crisis. Based on precedent in the area and in world history, I argue in this paper that the Philippine government's relia...

A fantasia da história feminista, 2024

Dal Barocco a Manzoni. Percorsi nella narrativa tra Sei e Ottocento per Quinto Marini, 2024

OPSIS, 2018

American Literary History

A pesquisa em saúde: desafios atuais e perspectivas futuras 6 (Atena Editora), 2023

Academic Medicine, 2012

CBU International Conference Proceedings, 2015

Harm Reduction Journal, 2022

PsycEXTRA Dataset

Clinical Neurophysiology, 2010

Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2009

Sustainability

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology, 2003

American Journal of Physiology-endocrinology and Metabolism, 2005

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

Amid China Tensions, the Philippines Relies on Alliances and Rule of Law

From its aggressive maritime actions to its new ‘10-dash line,’ Beijing flouts the rules-based order that Manila seeks to uphold.

By: Victor Andres “Dindo” C. Manhit

Publication Type: Analysis

A diplomatic win, many people said about the announcement of a hotline between the Philippines and China. This was one of the highlights of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s trip to China in January 2023, where he and Chinese President Xi Jinping established a direct line of communications between their two capitals. Specifically, the line would be between departments in each country’s foreign affairs ministries that deal with maritime and border issues. The objective was to prevent the escalation of tension in the West Philippine Sea (also referred to as the South China Sea).

In an interview, Marcos Jr. said he proposed the direct communication mechanism to elevate official communication between the two countries to a ministerial level. It would be a confidence-building measure to improve the trust of both sides.

The hotline was put to the test seven months later.

On August 5, the Chinese Coast Guard fired water cannons at Philippine boats that were on a resupply mission to the BRP Sierra Madre, off Ayungin Shoal, clearly within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone. A Philippine government representative privy to what was happening behind the scenes said there were frantic efforts to contact the Chinese, specifically through the hotline provided. But calls during the height of the crisis remained unanswered.

We at the Stratbase ADR Institute, together with the U.S. Institute of Peace, held a dialogue on crisis communications in the week following this incident. There were many insights regarding China’s action, or more accurately, non-action with regard to the hotline. It could be that China did not believe what was happening was an emergency or a crisis. The hotline was there, but the incident, at least from the Chinese point of view, was not cause for alarm. And why should it cause alarm? Beijing’s Coast Guard fired the water cannons in the first place.

It could be that for China, the hotline’s establishment was merely for optics. They wanted to appear as though they were listening and ready to talk. The operative word is “appear.” China has been known to say one thing and do the exact opposite. In a joint statement issued during Marcos Jr.’s state visit, the two countries mutually agreed to manage differences in the West Philippine Sea through peaceful means. However, recent sea encounters between the two countries, including the pointing of military-grade lasers, and blocking of resupply missions to Ayungin shoal, among other acts of bullying, prove otherwise.

Experts have suggested many ways to respond to this. “Keep talking,” seemed to be the consensus. Make the issue mainstream. Let civilians, ordinary Filipinos, be aware this is a threat to our sovereignty. Focus on other aspects of country-to-country relations, like trade and economics, instead of confining the matter to security.

The important question though is: Would the hotline still serve a purpose in future similar incidents?

China’s 10-Dash Line

On August 28, China made another bold move: It published what it called a new standard map that now included 10 dash lines, not nine as it had been claiming for a long time. The 2016 decision of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which ruled in the Philippines’ favor, dismissed China’s nine-dash rule as the basis for its claims in the South China Sea and for its aggressive actions.

As expected, expressions of outrage and condemnation over the 10-dash line were quick to come from different countries. Indeed, the new map is an insult to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 2016 arbitral decision. It is very obviously a desperate attempt to disrupt the rules-based international order.

Soon after, the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) issued a statement rejecting this map. It said that China’s attempt to legitimize its jurisdiction over the West Philippine Sea had no basis under international law. It called on China to “act responsibly and abide by its obligations and UNCLOS and the final and binding 2016 Arbitral Award.” On the same day, the DFA filed a diplomatic protest rejecting the map and calling for a peaceful resolution of the issue.

Other countries expressed similar sentiments. Malaysia lodged a diplomatic protest, noting that the map reflects China’s unilateral claims in the South China Sea near the states of Sabah and Sarawak. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stressed that the map had no binding authority over Malaysia.

Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that the inclusion of Vietnam’s Paracel and Spratly islands in the new standard map is a violation of its sovereignty, sovereign rights, and jurisdictional rights under UNCLOS, and noted that the new map held no value as it blatantly disregards international law. Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi also stated that any line drawn on the map must be in accordance with UNCLOS.

The Stratbase ADR Institute issued a message , strongly and categorically rejecting China’s desperate attempt to legitimize its territorial claims. We added that it is a mockery of the rules-based international order and of basic decency.

In our statement, we noted that the publication of the map “has the dangerous potential of propagating disinformation by advancing the Chinese narrative that the West Philippine Sea is part of their territory. No attempt to redraw geopolitical boundaries will make this acceptable, as this is a blatant violation of international law.”

We applauded like-minded states that have also stood up against China’s map, which represent an expansionist agenda. “The Philippines, its allies, and partners must remain firm in defending the rules-based international order through strategic cooperation to maintain a united front against coercive and antagonistic states,” we said, reiterating that because of the Philippines’ arbitral victory, we are on the right side of history.

But despite efforts of the Philippines and other countries to stand up to China’s bullying and to call it out on its actions, China has remained undaunted. The Chinese Coast Guard continues to make trouble for Philippine boats off Ayungin. There are also recent reports of massive coral reef damage in Philippine territory.

And yet, in the recent Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit held last September in Indonesia, the statement of the ASEAN chair made no mention whatsoever of China’s 10-dash line. ASEAN members are also yet to finalize a Code of Conduct for the South China Sea, and individual members of the regional bloc have different sentiments on the issue given their respective bilateral relations with China.

Relying on Allies and the Rules-Based Order

Despite these continuing challenges, the Philippines remains hopeful.

Foremost, this current administration is making a stark departure from the foreign policy stance of its immediate predecessor. Former President Rodrigo Duterte made a vocal and visible pivot to China, claiming this was in pursuit of an independent foreign policy. What it was, in fact, was a policy of appeasement and accommodation, much to the Philippines’ security and even economic detriment.

The current president, Marcos Jr., immediately distanced himself from Duterte’s pro-China policy and was careful to say that only the national interest will dictate his administration’s foreign policy positions. The Philippines will be a friend to all and an enemy to none, he said. These words are aligned with the current geopolitical situation: the world has become multipolar, with not two but many different significant powers, and with numerous traditional, non-traditional and emerging threats.

Backing up Marcos’ pronouncements are various agreements and cooperative bilateral, multilateral and minilateral actions undertaken with states that cherish the same values and principles as the Philippines. The United States, for instance, has remained the most trusted country among Filipinos, according to the most recent Stratbase-commissioned survey by the polling firm Pulse Asia.

In that same survey, conducted in June of this year, 80% of respondents nationwide agreed that alliances should be formed, and relationships should be strengthened, with countries with beliefs similar to those of the Philippines. This is to defend the territory and economic rights of the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea and protect the international order.

There are three measures that the Marcos administration should focus on to address the West Philippine Sea issue, according to the survey. Seventy-two percent believe that strengthening the military should be a government priority. Meanwhile, 64% think conducting joint maritime patrols and military exercises with allied countries should also be a priority. Finally, 61% of respondents believe that shifting the focus of Philippine defense institutions and allocating resources to strengthen our ability to defend the country from external threats should likewise be given attention.

Overcoming China’s Rejection of International Law

So, was the so-called hotline a failure?

Even before the announcement of the hotline in January, there has always been an established channel of communication between the Philippines and China. We have always been able to issue notes verbales and talk with Chinese authorities regarding our concerns.

But responsive and meaningful communication between the Philippines and China hinges on the latter’s recognition of its obligations to the international community to respect the territorial integrity and national sovereignty of its counterparts, in general, and the Philippines’ legal victory in 2016 in particular.

Certainly, there is much to be desired in the ongoing relationship between the Philippines and China, and in the pursuit of peace and stability in the West Philippine Sea and in the Indo-Pacific region. Like other countries that respect the established rules-based international order, the Philippines is hopeful that existing mechanisms will be enough to preserve the rule of law, and that the expansionist, aggressive actions of some actors will be highlighted and discouraged on the international stage.

As tensions with China simmer , the Philippines should continue to work with its friends and allies, whose support and cooperation is the real diplomatic win, and the real confidence-building measure, for Manila.

Victor Andres “Dindo” C. Manhit is the president of the Stratbase ADR Institute for Strategic and International Studies.

Related Publications

At SCO, Pakistan Promotes Relevance as China Projects Influence

Thursday, October 24, 2024

By: Daniel Markey, Ph.D. ; Amna Rana

Last week, Pakistan hosted leaders from China, Russia, India, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Iran and Belarus for the 23rd Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit. While the lead-up to the summit highlighted the constraints that Pakistan’s internal troubles place on its ability to play an active role in global diplomacy, Islamabad was able to sidestep any serious diplomatic faux pas. India’s attendance may have left a door cracked to dialogue between Pakistan and its neighboring rival.

Type: Question and Answer

Global Policy

China Responds to Taiwan’s Plea for Cross-Strait Peace with Military Pressure

By: Naiyu Kuo ; Dan Spinelli ; Jennifer Staats, Ph.D.

In his first National Day speech as Taiwan’s president, William Lai Ching-te called for regional peace while reaffirming that China and Taiwan “are not subordinate to each other.” Though Lai’s October 10 address was more restrained than past remarks, it was attacked by China’s state media as “highly provocative.” Days later, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) encircled Taiwan with record numbers of military aircraft and warships during a series of military “drills.”

Conflict Analysis & Prevention

In the Pacific, Aid Should Be About More than Competition with China

Thursday, October 17, 2024

By: Gordon Peake, Ph.D. ; Meghan Sullivan

Outside powers often treat aid as an easy geopolitical win in the Pacific. However, Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) Minister for National Planning Sir Ano Pala’s recent public critique of Australian aid at Australia’s latest development plan launch in PNG punctured this perception. Pala’s statement should serve as a reminder that Pacific Island countries won’t be bought with aid packages in the tussle for geopolitical influence in the region, particularly those that do not align with Pacific priorities or build local capacities.

Type: Analysis

What’s Driving a Bigger BRICS and What Does it Mean for the U.S.?

By: Adam Gallagher ; Andrew Cheatham

Leaders from Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) will gather in Kazan, Russia, next week for the group’s annual summit, along with an expanded roster of members. This is the first BRICS summit since Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE joined earlier this year. Russia, which holds the BRICS presidency this year, has also invited over two dozen other countries, which have expressed interest in joining the group, for the first “BRICS+” summit. For President Vladimir Putin, hosting this summit is an opportunity to show that Western efforts to isolate Moscow for its illegal war on Ukraine have not been successful and that Russia has friends around the globe.

Through 2023, tensions in the South China Sea between China and the Philippines have escalated, marked by such significant escalations as the removal of a floating barrier by the Philippines near the Scarborough Shoal and the deployment of its Coast Guard amid increased activity by the Chinese Maritime Militia (CMM) near Julian Felipe Reef (or Whitsun Reef). These incidents underscore the long-standing territorial disputes in this heavily trafficked shipping lane, and underpin a growing global maritime conflict.

Who are the parties involved in the territorial dispute?

There are three key parties involved in the current South China Sea territorial dispute: China, the Philippines, and the US.

China has long claimed much of the South China Sea under its Nine-Dash Line approach to territorial integrity. The Nine-Dash Line refers to maps produced by China that allege that China has a territorial claim on what it states are not “shoals” or “low-tide land masses” but islands in the South China Sea. If they are islands under Chinese control, this would expand China’s territory under international maritime law. China has never clarified if this means the area is part of China’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), meaning the country has full control of economic activity in the area used, or if China merely views the area as under its jurisdiction, implying a more moderate level of control. China has attempted to strengthen its claim by “reclaiming” islands in the area via dredging; however, many countries have asserted these are completely artificial islands rather than “reclaimed” islands.

There are two main Chinese organizations in the South China Sea asserting China’s claims. The first is the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG). The CCG is a branch of the Chinese military and is the most official Chinese organization enforcing China’s asserted territorial integrity. The second Chinese group in the South China Sea is the Chinese Maritime Militia (CMM). The CMM was established in the 1960s when China set up multiple maritime militia schools for fishermen. Starting in the 1970s, China began to use the CMM to assert its claims of sovereignty. While the CMM is an officially sanctioned Chinese organization, it is not an official branch of the military.

The Philippines

The Philippines’ territorial claims in the South China Sea (which it calls the West Philippine Sea) are largely based on historical fishing ground claims. The country also asserts that what China claims are “islands” are actually “low-tide land masses” and shoals, which are therefore part of the Philippines’ EEZ. Starting in the 1970s, the Philippines began strongly asserting its territorial ownership of the Scarborough Shoal and other nearby shoals and land masses.

The US began its heavy involvement in the area on behalf of the Philippines in the South China Sea around 2015, when it began to hold regular “freedom of navigation operations” (FONOP) in the region. However, the US has had a reciprocal ally relationship with the Philippines since 1951, including bases and military presence on the Philippines’ territory. Ever since 2015, the US has held regular military exercises in the South China Sea in support of the Philippines, with the most recent taking place in November.

Other countries with territorial claims

There are several other countries with competing territorial claims in the South China Sea, including Brunei, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

Relevant International Law:

2016 Arbitral Agreement

The territorial dispute between China and the Philippines reached a head in 2013 when the Philippines brought a case against China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in the Hague challenging China’s territorial claims. The PCA released its ruling in 2016, largely siding with the Philippines in the territorial dispute. The PCA ruling (also called the 2016 Arbitral Agreement) stated that China’s Nine-Dash Line territorial claims were not legally supported; China violated the Philippines’ territorial integrity, and China’s reclamation activities in the disputed area violated international environmental law. China has since rejected the ruling and continued claiming territorial rights in the area. This agreement is the primary source of international law used by both the Philippines and the US to assert the area near the Scarborough Shoal is part of the Philippines’ EEZ.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the second key source used by the US and the Philippines to assert the disputed area is part of the Philippines’ EEZ. Three key sections of UNCLOS apply to the territorial dispute. The first is Section 2 Article 3, which states, “Every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention.” But what are the baselines from where the 12 nautical mile measurement should start? This question is answered by the second important part of UNCLOS, Section 2 Article 13. Article 13 states:

- A low-tide elevation is a naturally formed area of land which is surrounded by and above water at low tide but submerged at high tide. Where a low-tide elevation is situated wholly or partly at a distance not exceeding the breadth of the territorial sea from the mainland or an island, the low-water line on that elevation may be used as the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea.

- Where a low-tide elevation is wholly situated at a distance exceeding the breadth of the territorial sea from the mainland or an island, it has no territorial sea of its own.

This article is one of the reasons why China has attempted to claim that some of the shoals in the area are islands and has attempted to “reclaim” islands nearby. If they are islands, then China could measure its baseline from the “low-tide elevation” in dispute, as it would be situated “at a distance not exceeding the breadth of the territorial sea from…an island.” However, the 2016 Arbitral Award dismissed this interpretation, ruling that the “islands” in question were not islands, making the “low-tide elevations” part of the Philippines’ EEZ.

The third important part of UNCLOS is Part 8, Article 121, which governs what is and is not an island. Article 121 states, “An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide…Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” This article was one of the key sections of UNCLOS cited in the 2016 Arbitral Award, as the “islands” China alleged its territorial area emanated from were determined to be uninhabitable, and therefore did not provide justification for China’s territorial claims.

COLREGS and the 2002 ASEAN China Declaration

While the Arbitral Agreement and UNCLOS are the two main maritime legal instruments relevant to the South China Sea territorial dispute, two other legal documents have been referenced during the ongoing conflict. The first is the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGS). These international maritime regulations specifically govern collisions, both purposeful and accidental, and have come up recently during an incident in which an alleged CMM vessel rammed a PCG vessel. The second is the 2002 ASEAN China Declaration , which was a declaration agreed to by China and the members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (including the Philippines), committing the signatories to peaceful resolutions of territorial disputes and freedom of passage within the South China Sea.

Increasing tensions in 2023:

2023 has been a year marred by increased tensions between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea. In September, the Philippines removed a floating barrier near the Scarborough Shoal, which the PCG alleged was placed by China. The PCG also claimed that the CCG hailed and harassed several Filipino fishermen in the area. In November, President Xi Jinping of China and Philippine President Ferdinand “BongBong” Marcos Jr. met during the APEC conference in San Francisco, US, and discussed the ongoing tensions. Days later the US and the Philippines held military exercises in the disputed area. Then, in early December, the PCG deployed two ships to the Julian Felipe Reef in response to an alleged increase in CMM activity. Most recently, the Philippines summoned the Chinese ambassador to the Philippines after an incident in which a boat carrying the Philippine Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces, General Romeo Brawner was allegedly sprayed with water cannons and rammed by a CMM vessel. The CCG has denied these allegations.

Why is the South China Sea important?

The South China Sea is an incredibly important area, as it is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, with over $5.3 trillion in goods moving through it. The area is also rich in oil and natural gas, with some estimates putting the total oil and gas content at over 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

United Nations Day

October 24 is United Nations Day . On October 24, 1945, the UN Charter, signed on June 26, 1945, formally entered into force. Review the text of the UN Charter .

Civil Rights pioneers Jackie Robinson and Rosa Parks die

On October 24, 1972, the first African-American to play Major League Baseball, Jackie Robinson, died at the age of 53 in Stamford, Connecticut. On the same day in 2005, Rosa Parks passed away in Detroit at the age of 92. Parks inspired the Montgomery Bus Boycott when she was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on the bus to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama. Both Parks and Robinson were symbols of the civil rights movement, which led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act .

- Asia Briefing

- China Briefing

- ASEAN Briefing

- India Briefing

- Vietnam Briefing

- Silk Road Briefing

- Russia Briefing

- Middle East Briefing

- Asia Investment Research

The Philippines’ Economic and Political Relations With China

Op-ed by Bob Shead

The focus of this article is a very complicated but important regional issue in ASEAN – the current state of the economic, trade and political relations between the Philippines and the Peoples Republic of China. The election of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016 has in fact changed the strategy and effects of this relationship. Last year, this relationship was described by the Huffington Post , as the most toxic in Asia, when Duterte’s predecessor, President Aquino was in charge. However, since President Duterte took office last year, he has extended a hand of economic and political cooperation to China, and his official visit to Beijing last October, was an economically productive visit as it was formative in securing investment and credit line pledges that amounted to approximately US$ 24 billion in business and trade deals for the Philippines.

However, what has attracted much international economic interest and criticism has been Duterte’s position over the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea maritime disputes, where he has recently stated that the Philippines cannot stop China from building military and government facilities on the disputed shoals, although the Hague-based International Arbitration Tribunal ruled in 2015 that the internationally agreed Philippine Maritime Territory must be observed by China. China opposed this decision and has gone ahead in developing these shoals into permanent military and government occupied bases.

These actions meant that, under the previous Aquino Government, the Philippines has postponed formal membership in the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and has questioned the agenda behind and the overall transparency of its governing structure. Clearly, the South China disputes are defining the overall texture of Philippine-China relations. Additionally, it is estimated that the undiscovered natural gas and oil deposits under the Philippine Maritime Territory may be amongst some of the largest unexplored resources globally. China would obviously like to have control of these resources. However, as shown in the figures below, trade and economic cooperation between the two countries has dramatically increased, despite the political differences, and this is expected to continue.

Provided below is a quick overview of the relationship between the Philippines and China (these latest available figures are up to date as of 2015).

ECONOMY AND TRADE

- US$ 1.272 billion in development assistance to the Philippines from China from 2002 until 2013 (not including the results of the recent visit to Beijing – as referred to below).

- US$ 17.646 billion worth of bilateral trade between China and the Philippines in 2015.

- US$ 6.175 billion worth of Philippine. exports to China in 2015.

- US$ 11.471 billion in Philippine imports from China in 2015.

- US$ 1.455 billion in Chinese investments in the Philippines in 2015.

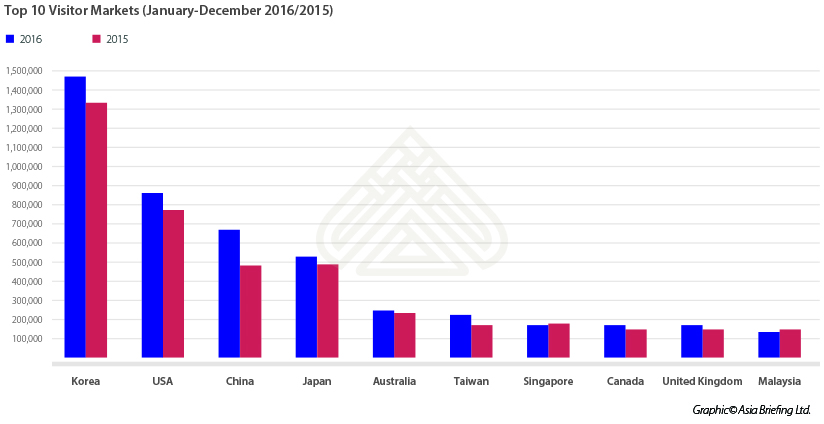

- An estimated 680,000 Chinese visitors to the Philippines in 2016.

- An estimated 1.2 million Filipino visitors to China in 2016.

- Tourism from China to Philippines will increase and is a good source of revenue for the Philippines. The figures for 2017 are expected to increase rapidly, and the casino industry is expected to be one of the major beneficiaries.

BILATERAL AGREEMENTS – Philippines and China

- 1978 Scientific and Technological Cooperation Agreement

- 1979 Cultural Cooperation Agreement, Civil Aviation and Transportation Agreement

- 2001 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) on Sports Cooperation

- 2001 Cooperation in Information Industry

- 2001 Cooperation in the Crackdown on Transnational Crimes

- 2001 Treaty on Extradition

- 2001 Pact on Cooperation Against Illicit Traffic and Abuse of Narcotic Drugs

- 2002 MOU on Tourism Cooperation

- 2005 MOU on Maritime Cooperation

- 2005 Pact on Cooperation in Youth Affairs

- 2007 MOU on Cooperation in Sanitary and Phytosanitary Cooperation, Education Cooperation

- 2007 Pact on Protection of Cultural Heritage

- 2008 Pact on Sanitary Cooperation

Philippine-China Trade Figures including comparisons with Japan and USA

The Philippines posted a US$ 2.31 billion trade deficit in January 2017, compared to a US$ 2.64 billion gap a year earlier, as exports rose more than imports. In December 2016, the Philippines total trade deficit was US$ 2.16 billion.

Year-on-year sales increased by 22.5% to US$ 5.13 billion in January 2017, following an upward revised 6.3% rise in December 2016, which marked the fastest rise in three years. Outbound shipments rose by 270.1% for articles of apparel and clothing accessories, by 229.6% for coconut oil, by 104.7% for chemicals, by 66.3% for metal components, by 64.8% for electronic equipment and parts, by 58.8% for other manufacturing, by 27.9% for transport machinery and equipment, and by 10.4% for electronic products. Sales of electronic products, the top export earner for the Philippines increased by 10.4%. In contrast, exports decreased by 24.7% for wood products (including furniture) and by 5% for ignition wiring sets used in all forms of transport vehicles ( including aviation and maritime).

Exports to Mainland China increased by 23.6%, while exports to Hong Kong increased by 20.7%, USA by 21.2%, Singapore by 16.8%, other ASEAN countries 19.3%, and EU countries by 82.5%. In contrast, sales to Japan, the previous top export destination for the Philippines, decreased by 6.6%.

Imports rose by 9.1% year-on-year to US$ 7.44 billion in January 2017; this was lower than the previously projected increase of 13.8% in December, which resulted in a decrease since October 2016. However purchases increased by 79.7% for transport equipment and iron and steel; by 42.7% for mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials; by 30.6% for cereals and cereal preparations; by 28.6% for miscellaneous manufactured articles; by 24% for telecommunication equipment and electrical machinery; by 23.3% for plastics in primary and non-primary forms; by 13.4% for other food and live animals; and by 11.1% for industrial machinery and equipment. In contrast, imports shrank for electronic products by 16.2% and for transport equipment by 9.5%.

Purchases from China, the country’s biggest source of imports, went up by 26.4%, followed by Japan 10.8%, South Korea 19.7%, and ASEAN member countries 16.2%. Purchases from EU countries fell by 27.2% and imports from the US dropped by 6.9%.

Japan was the country’s top trading partner in 2015, accounting for a total trade worth US$ 18.669 billion or 14.4% of the Philippines’s total trade. Exports to Japan totaled US$ 12.301 billion, while imports were valued at US$ 6.369 billion, posting a trade surplus of US$ 5.932 billion. Electronic Products took the largest share of 30.2% of the total exports to Japan valued at US$ 3.721 billion, followed by Wood products (including furniture) at US$ 2.853 billion or 23.2%. In comparison, majority of the imported products from Japan were Electronic Products at US$ 2.193 billion or 34.4% and Transport Equipment with US$ 962.86 million or 15.1%.

China was the Philippines’ second largest trading partner in 2015 with total trade worth US$ 17.646 billion or 13.6% of the total Philippines-China trade. Exports from China totaled US$ 6.175 billion, while payment for imports was valued at US$ 11.471 billion; this resulted in a US$ 5.296 billion trade deficit with China. From an export viewpoint, the biggest sales to China were Electronic Products valued at US$ 3.388 billion or 54.9% of the country’s exports to China. Other Mineral Products followed with a total value of US$ 683.41 million or 11.1%. Imported goods purchased from China were made up of Electronic Products valued at US$ 2.418 billion or 21.1% of the country’s total imports, with Iron and Steel following at US$ 1.823 billion or 15.9%.

The USA was placed third, and accounted US$ 16.491 billion or 12.7% in total trade with the Philippines in 2015. Exports to the USA were priced at US$ 9.023 billion while imports totaled US$ 7.468 billion and this reflected a trade surplus of US$ 1.554 billion. The majority of the exports were Electronic Products valued at US$ 3.557 billion or 39.4% of the total exports to USA and Clothing Articles priced at US$ 1.014 billion or an 11.2% share. Major inward shipments from USA were Electronic Products valued at US$ 3.322 billion or 44.5% of the total. Animal Feed ranked second and was priced at US$ 716.17 million or 9.6% of the total imports from the USA.

Benefits and Trade Details following Duterte’s visit to China in October 2016

There were massive trade benefits for the Philippines, during the visit last year by President Duterte, as he wrapped up the State Visit to China, securing investment and credit line pledges amounting to US$ 24 billion, or nearly double the initial amount reported.

Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez said, at the time, that the total amount included US$ 15 billion worth of investment projects and US$ 9 billion in credit facilities. Earlier estimates had placed the total trade package at US$ 13.5 billion.

There was apparently 17 extra trade deals, with a combined value of US$ 11.24 billion that were signed following the meeting between the two leaders, at an event organized by the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industries (PCCI) and the Federation of Filipino Chinese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FFCCCI). Amongst these extra deals were the following:

The Philippine mining firm Global Ferronickel signed a US$ 500-US$ 700 million deal with Baiyin International Investment Ltd to construct a steel plant, while Greenenergy Development Corp. signed a MOU with PowerChina Guizhou Engineering Corp to develop a 300Mw hydropower plant project valued at approximately US$ 1 billion.

Another Philippine company MVP Global Infrastructure Group Ltd with a focus on joint investments with major Mainland Chinese companies who are already operating in Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines, also signed large (unspecified) investment deals. The MVP Group also signed an MOU to establish a partnership with China Railway Engineering Corp to build infrastructure investments projects valued at US$ 2.5 billion.

There were projects with the Suli Group to invest in cabling manufacturing facilities in the Philippines valued at US$ 3 billion, plus a US$ 780 million contract for the Mega Harbour Port signed with China Harbour Engineering Company to complete a 214 hectare coastline project.

It is obvious that the Philippines is rapidly improving its trading and economic position with the ASEAN region, however with this, it should be noted that there remain many difficult and large social and related issues, that need to be tackled. The Philippine-China relationship remains precarious, and mainly due to the maritime disputes, as yet unresolved, and will of course reflect of the Philippines economy and trade. The current President and his Government do have a good and reputable group of economic advisers behind them and without a doubt the Philippines economy is rising from a previously poor situation. Its trade relations with China remain of great importance, and despite all the issues mentioned above, I suspect will continue to improve, hopefully to the benefit of both countries.

- Previous Article ASEAN Market Watch: Indonesia Automotive Market, Malaysia-India Trade, and ASEAN Manufacturing Sector

- Next Article Aperçu de l’Industrie Automobile en Thaïlande

Our free webinars are packed full of useful information for doing business in ASEAN.

DEZAN SHIRA & ASSOCIATES

Meet the firm behind our content. Visit their website to see how their services can help your business succeed.

Want the Latest Sent to Your Inbox?

Subscribing grants you this, plus free access to our articles and magazines.

Get free access to our subscriptions and publications

Subscribe to receive weekly ASEAN Briefing news updates, our latest doing business publications, and access to our Asia archives.

Your trusted source for India business, regulatory and economy news, since 1999.

Subscribe now to receive our weekly ASEAN Edition newsletter. Its free with no strings attached.

Not convinced? Click here to see our last week's issue.

Search our guides, media and news archives

Type keyword to begin searching...

the philippines and its diplomatic relationship with china essay

Copy link and share

Qwen1.5 72B

Title: Philippine-China Diplomatic Relations: A Balancing Act

Introduction

The Philippines and China, two key players in Southeast Asia, have had a complex and evolving diplomatic relationship that is deeply rooted in history, geographical proximity, and strategic interests. Over the years, this relationship has been shaped by various factors, including trade, cultural exchanges, territorial disputes, and the influence of global politics. This essay aims to explore the nuances of the bilateral ties between these nations, focusing on the challenges, opportunities, and the delicate balancing act that has characterized their interaction.

Historical Background

The history of Philippine-China relations dates back to ancient times when trade routes connected the two nations. Cultural exchanges flourished, with Chinese merchants playing a significant role in the development of Philippine commerce. Diplomatic relations were officially established on June 9, 1975, during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, marking the beginning of a new era of cooperation.

Economic Cooperation

Economic collaboration has been a cornerstone of the Philippines-China relationship. China has become one of the Philippines’ leading trade partners, with bilateral trade reaching record highs in recent years. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has provided opportunities for infrastructure development, investments, and economic cooperation, leading to increased diplomatic engagement.

Territorial Disputes

However, the relationship has been marked by disputes, primarily over overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea. The Philippines contests China’s claims in the area, particularly within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This tension culminated in the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling, which favored the Philippines, invalidating China’s historic claims. Despite this, China has not recognized the decision, creating a significant diplomatic challenge.

Diplomatic Balancing and Multilateralism

The Philippines, under the administrations of different presidents, has employed a diplomatic balancing act to manage this delicate relationship. This includes engaging China bilaterally while also seeking support from regional partners, such as ASEAN, and global allies, like the United States. This strategy aims to maintain peaceful relations with China while safeguarding national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

The Role of the United States

The U.S., as an ally of the Philippines, has played a crucial role in the country’s foreign policy. The mutual defense treaty and increased military cooperation have provided a security cushion for the Philippines in its dealings with China. However, this dependence on the U.S. can sometimes strain Manila’s relations with Beijing.

Future Prospects

Moving forward, the Philippines and China must continue to engage in dialogue and cooperative efforts to stabilize their relationship. This includes exploring mechanisms for addressing territorial disputes peacefully, enhancing economic cooperation, and fostering cultural exchanges. The recent years have seen increased dialogue and cooperation on areas such as counterterrorism, drug rehabilitation, and COVID-19 response, indicating potential for further diplomatic progress.

In conclusion, the Philippines-China diplomatic relationship is a complex web of cooperation and contention. Despite challenges posed by territorial disputes, the two nations have managed to maintain a delicate balance by focusing on economic collaboration and engaging in dialogue. As both countries look to navigate the evolving regional and global landscape, fostering mutual respect, trust, and a commitment to peaceful resolution of disputes will be essential for a sustainable and prosperous relationship.

Here is a sample essay on the Philippines’ diplomatic relationship with China:

The Philippines and China have a complex and multifaceted diplomatic relationship that has evolved over the centuries. From being one of the first countries to establish diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China in 1975, the Philippines has maintained a delicate balance in its relations with its giant neighbor.

Historically, the Philippines and China have had a long-standing relationship, with trade and cultural exchanges dating back to the ancient times. However, the modern diplomatic relationship between the two countries began in 1975, when the Philippines, under the Marcos regime, formally established diplomatic ties with China. This move was seen as a strategic decision to diversify the country’s foreign policy and reduce its dependence on the United States.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Philippines-China relationship remained relatively stable, with both countries cooperating on various issues such as trade, tourism, and education. However, the relationship took a significant turn in the 2000s, when the Philippines and China began to dispute over territorial claims in the South China Sea. The Philippines, along with other Southeast Asian countries, claimed sovereignty over certain islands and reefs in the area, while China asserted its dominance over the entire region.

The tensions between the two countries escalated in 2012, when the Philippines and China engaged in a standoff over the Scarborough Shoal, a disputed territory in the South China Sea. The Philippines sought international arbitration, which led to a 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in favor of the Philippines. However, China refused to recognize the ruling, leading to increased tensions and military build-up in the region.

Despite the tensions, the Philippines, under the Duterte administration, has adopted a more pragmatic approach towards China. In 2016, Duterte announced a “separation” from the United States and a pivot towards China, seeking to strengthen economic ties and secure investments from Beijing. China has since become one of the Philippines’ largest trading partners, with bilateral trade reaching $50 billion in 2020.

However, critics argue that the Philippines’ rapprochement with China has come at the cost of its sovereignty and territorial integrity. China’s continued militarization of the South China Sea and its refusal to recognize the 2016 arbitration ruling have raised concerns about the Philippines’ ability to protect its territorial claims. Furthermore, the influx of Chinese investments and tourists has raised concerns about the environmental and social impacts on the Philippines.

In recent years, the Philippines has sought to balance its relationship with China by strengthening ties with other countries, including the United States, Japan, and Australia. The Philippines has also sought to promote regional cooperation through the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), emphasizing the need for a peaceful and stable regional order.

In conclusion, the Philippines’ diplomatic relationship with China is complex and multifaceted, marked by periods of cooperation and tension. While the Philippines has sought to strengthen economic ties with China, it must also protect its sovereignty and territorial integrity. As the Philippines navigates its relationship with China, it must adopt a nuanced and pragmatic approach that balances its national interests with regional and global considerations.

- “A History of Philippines-China Relations” by the Philippine Embassy in China

- “Philippines-China Relations: A Review of the Past 40 Years” by the Asian Institute of Management

- “The Philippines’ Pivot to China: A Critical Assessment” by the Center for Strategic and International Studies

- “The South China Sea Disputes: A Review of the Philippines’ Position” by the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs

The Philippines and China: A Complex Diplomatic Relationship

The relationship between the Philippines and China is multifaceted and fraught with complexities. It is characterized by a delicate balance of cooperation, competition, and territorial disputes.

Historical Context:

The Philippines and China have a long and complex history intertwined. China colonized the Philippines for over 300 years, leaving behind a lasting cultural and linguistic influence. This shared heritage forms a basis for cultural understanding and potential cooperation.

Economic and Trade Relations:

Economic cooperation is a crucial aspect of the bilateral relationship. China is the Philippines’ second-largest trading partner, and the two countries engage in extensive trade in goods and services. This economic interdependence fosters a desire for stability and cooperation.

Territorial Disputes:

However, the relationship is marred by ongoing territorial disputes in the South China Sea. China’s assertive territorial claims and construction activities in the area generate tensions and raise anxieties in the Philippines. This ongoing dispute poses a significant threat to regional stability and raises concerns about the future of Philippine-Chinese relations.

Political and Strategic Interests:

Both countries have competing political and strategic interests in the region. China’s rise as a global power challenges the US dominance, while the Philippines seeks to maintain its close alliance with the United States. This competition can create tensions and complicate the bilateral relationship.

Areas of Cooperation:

Despite the challenges, there are areas of potential cooperation between the two countries. These include:

- Infrastructure development: China has offered significant financial assistance for infrastructure projects in the Philippines.

- Climate change: Both countries face significant climate change challenges, and cooperation on climate action is a potential area for collaboration.

- Public health: Cooperation on public health issues like pandemic response and disease prevention could further strengthen the relationship.

Future Prospects:

The future of Philippine-Chinese relations remains uncertain. While there are potential areas for cooperation, the territorial disputes and competing interests pose significant challenges. Both countries need to find ways to manage their differences and work towards a more cooperative and stable relationship.

Conclusion:

The Philippines and China relationship is multifaceted and requires careful management. While there are opportunities for cooperation, resolving the territorial dispute and managing competition will be crucial for ensuring a peaceful and prosperous future for both countries.

The Philippines and its Diplomatic Relationship with China: An Analysis

The Philippines and China have a complex and dynamic diplomatic relationship that has evolved over the years. The two countries share a long history, cultural ties, and economic interdependence, but their relationship has also been marked by territorial disputes and geopolitical tensions. This essay will analyze the current state of the Philippines-China relationship, its historical background, and the factors that have shaped it.

The Philippines and China have had diplomatic relations since the 1970s, but their relationship can be traced back to the pre-colonial era. During the Ming Dynasty, Chinese merchants and missionaries visited the Philippines, and there are records of Filipino envoys visiting China as well. The Spanish colonization of the Philippines in the 16th century disrupted this relationship, but it was revived during the American colonial period when the Philippines became a US territory.

After gaining independence in 1946, the Philippines established diplomatic relations with China in 1975. The relationship was initially cordial, with both countries signing a joint communique in 1

Mixtral 8x7b

Title: The Philippines and Its Diplomatic Relationship with China: A Delicate Balance

The Philippines, an archipelago nation in Southeast Asia, has a complex and multifaceted diplomatic relationship with its neighbor, China. This relationship is marked by both cooperation and competition, with shared interests in economic development and cultural exchange coexisting with disputes over territorial claims in the South China Sea. This essay will provide a precise and balanced exploration of the historical context, current state, and future prospects of the Philippines-China diplomatic relationship.

Historical Context

The historical ties between the Philippines and China date back to the 10th century, with the establishment of trade relations during the Song Dynasty. However, the modern diplomatic relationship began in 1975 when the two countries established formal diplomatic ties. Since then, the relationship has experienced periods of both cooperation and conflict, influenced by factors such as changes in political leadership, national security concerns, and economic interests.

Current State

The current state of the Philippines-China diplomatic relationship is characterized by a mix of cooperation and competition. On the one hand, both countries have robust economic ties, with China being the Philippines’ second-largest trading partner and a major source of foreign direct investment. Additionally, there are ongoing cultural exchanges, people-to-people connections, and collaborations in areas such as education, science, and technology.

On the other hand, the relationship is strained by longstanding territorial disputes in the South China Sea. The Philippines, along with other Southeast Asian countries, has contested China’s expansive territorial claims, which have been met with growing Chinese military presence and assertiveness in the region. The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled in favor of the Philippines in 2016, but China has not recognized the ruling, maintaining its position and continuing its activities in the disputed areas.

The future of the Philippines-China diplomatic relationship will depend on several factors. First, the political leadership in both countries will play a crucial role in shaping the relationship. A more pragmatic and conciliatory approach from both sides could lead to the de-escalation of tensions and the promotion of shared interests.

Second, the management of territorial disputes will be a critical factor. Both countries need to find a peaceful and diplomatic solution that respects the rights and interests of all parties involved. This may include confidence-building measures, joint development projects, and the establishment of a multilateral framework for negotiations.

Third, the deepening of economic ties and people-to-people connections will continue to provide a strong foundation for the relationship. However, it is essential to ensure that these ties are balanced and mutually beneficial, rather than one-sided and exploitative.

Finally, regional and international dynamics will also influence the Philippines-China diplomatic relationship. The role of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the United States, and other major powers in the region will be vital in maintaining stability and promoting dialogue between the two countries.

In conclusion, the Philippines and China share a diplomatic relationship with both opportunities and challenges. While there are ongoing disputes and competition, there are also shared interests and cooperation in various fields. To ensure a stable and productive relationship, both countries must approach each other with kindness, understanding, and a commitment to peaceful dialogue and mutual respect. By doing so, the Philippines and China can build a relationship that benefits not only their two nations but also the wider region and the world.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In spring 2021, hundreds of Chinese fishing boats gathered at several South China Sea islets, most notably at Whitsun Reef, within the Philippines' exclusive economic zone. Worried that China might use the boats, which were suspected of being part of its maritime militia, to permanently occupy the reef, the Philippines dispatched navy and coast guard ships to the area. When Beijing called on ...

The Philippines government under President Rodrigo Duterte has attempted to navigate this entanglement by signalling its desire for closer relations with China, ostensibly because of how the ...