An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Introduction to qualitative research methods – Part I

Shagufta bhangu, fabien provost, carlo caduff.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Address for correspondence: Prof. Carlo Caduf, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2022 Nov 28; Accepted 2022 Nov 29; Issue date 2023 Jan-Mar.

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Qualitative research methods are widely used in the social sciences and the humanities, but they can also complement quantitative approaches used in clinical research. In this article, we discuss the key features and contributions of qualitative research methods.

Keywords: Qualitative research, social sciences, sociology

INTRODUCTION

Qualitative research methods refer to techniques of investigation that rely on nonstatistical and nonnumerical methods of data collection, analysis, and evidence production. Qualitative research techniques provide a lens for learning about nonquantifiable phenomena such as people's experiences, languages, histories, and cultures. In this article, we describe the strengths and role of qualitative research methods and how these can be employed in clinical research.

Although frequently employed in the social sciences and humanities, qualitative research methods can complement clinical research. These techniques can contribute to a better understanding of the social, cultural, political, and economic dimensions of health and illness. Social scientists and scholars in the humanities rely on a wide range of methods, including interviews, surveys, participant observation, focus groups, oral history, and archival research to examine both structural conditions and lived experience [ Figure 1 ]. Such research can not only provide robust and reliable data but can also humanize and add richness to our understanding of the ways in which people in different parts of the world perceive and experience illness and how they interact with medical institutions, systems, and therapeutics.

Examples of qualitative research techniques

Qualitative research methods should not be seen as tools that can be applied independently of theory. It is important for these tools to be based on more than just method. In their research, social scientists and scholars in the humanities emphasize social theory. Departing from a reductionist psychological model of individual behavior that often blames people for their illness, social theory focuses on relations – disease happens not simply in people but between people. This type of theoretically informed and empirically grounded research thus examines not just patients but interactions between a wide range of actors (e.g., patients, family members, friends, neighbors, local politicians, medical practitioners at all levels, and from many systems of medicine, researchers, policymakers) to give voice to the lived experiences, motivations, and constraints of all those who are touched by disease.

PHILOSOPHICAL FOUNDATIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

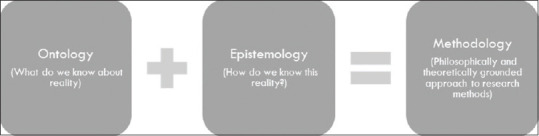

In identifying the factors that contribute to the occurrence and persistence of a phenomenon, it is paramount that we begin by asking the question: what do we know about this reality? How have we come to know this reality? These two processes, which we can refer to as the “what” question and the “how” question, are the two that all scientists (natural and social) grapple with in their research. We refer to these as the ontological and epistemological questions a research study must address. Together, they help us create a suitable methodology for any research study[ 1 ] [ Figure 2 ]. Therefore, as with quantitative methods, there must be a justifiable and logical method for understanding the world even for qualitative methods. By engaging with these two dimensions, the ontological and the epistemological, we open a path for learning that moves away from commonsensical understandings of the world, and the perpetuation of stereotypes and toward robust scientific knowledge production.

Developing a research methodology

Every discipline has a distinct research philosophy and way of viewing the world and conducting research. Philosophers and historians of science have extensively studied how these divisions and specializations have emerged over centuries.[ 1 , 2 , 3 ] The most important distinction between quantitative and qualitative research techniques lies in the nature of the data they study and analyze. While the former focus on statistical, numerical, and quantitative aspects of phenomena and employ the same in data collection and analysis, qualitative techniques focus on humanistic, descriptive, and qualitative aspects of phenomena.[ 4 ]

For the findings of any research study to be reliable, they must employ the appropriate research techniques that are uniquely tailored to the phenomena under investigation. To do so, researchers must choose techniques based on their specific research questions and understand the strengths and limitations of the different tools available to them. Since clinical work lies at the intersection of both natural and social phenomena, it means that it must study both: biological and physiological phenomena (natural, quantitative, and objective phenomena) and behavioral and cultural phenomena (social, qualitative, and subjective phenomena). Therefore, clinical researchers can gain from both sets of techniques in their efforts to produce medical knowledge and bring forth scientifically informed change.

KEY FEATURES AND CONTRIBUTIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS

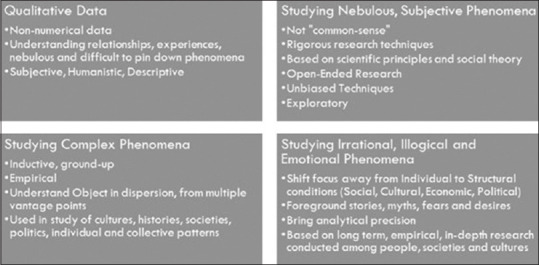

In this section, we discuss the key features and contributions of qualitative research methods [ Figure 3 ]. We describe the specific strengths and limitations of these techniques and discuss how they can be deployed in scientific investigations.

Key features of qualitative research methods

One of the most important contributions of qualitative research methods is that they provide rigorous, theoretically sound, and rational techniques for the analysis of subjective, nebulous, and difficult-to-pin-down phenomena. We are aware, for example, of the role that social factors play in health care but find it hard to qualify and quantify these in our research studies. Often, we find researchers basing their arguments on “common sense,” developing research studies based on assumptions about the people that are studied. Such commonsensical assumptions are perhaps among the greatest impediments to knowledge production. For example, in trying to understand stigma, surveys often make assumptions about its reasons and frequently associate it with vague and general common sense notions of “fear” and “lack of information.” While these may be at work, to make such assumptions based on commonsensical understandings, and without conducting research inhibit us from exploring the multiple social factors that are at work under the guise of stigma.

In unpacking commonsensical understandings and researching experiences, relationships, and other phenomena, qualitative researchers are assisted by their methodological commitment to open-ended research. By open-ended research, we mean that these techniques take on an unbiased and exploratory approach in which learnings from the field and from research participants, are recorded and analyzed to learn about the world.[ 5 ] This orientation is made possible by qualitative research techniques that are particularly effective in learning about specific social, cultural, economic, and political milieus.

Second, qualitative research methods equip us in studying complex phenomena. Qualitative research methods provide scientific tools for exploring and identifying the numerous contributing factors to an occurrence. Rather than establishing one or the other factor as more important, qualitative methods are open-ended, inductive (ground-up), and empirical. They allow us to understand the object of our analysis from multiple vantage points and in its dispersion and caution against predetermined notions of the object of inquiry. They encourage researchers instead to discover a reality that is not yet given, fixed, and predetermined by the methods that are used and the hypotheses that underlie the study.

Once the multiple factors at work in a phenomenon have been identified, we can employ quantitative techniques and embark on processes of measurement, establish patterns and regularities, and analyze the causal and correlated factors at work through statistical techniques. For example, a doctor may observe that there is a high patient drop-out in treatment. Before carrying out a study which relies on quantitative techniques, qualitative research methods such as conversation analysis, interviews, surveys, or even focus group discussions may prove more effective in learning about all the factors that are contributing to patient default. After identifying the multiple, intersecting factors, quantitative techniques can be deployed to measure each of these factors through techniques such as correlational or regression analyses. Here, the use of quantitative techniques without identifying the diverse factors influencing patient decisions would be premature. Qualitative techniques thus have a key role to play in investigations of complex realities and in conducting rich exploratory studies while embracing rigorous and philosophically grounded methodologies.

Third, apart from subjective, nebulous, and complex phenomena, qualitative research techniques are also effective in making sense of irrational, illogical, and emotional phenomena. These play an important role in understanding logics at work among patients, their families, and societies. Qualitative research techniques are aided by their ability to shift focus away from the individual as a unit of analysis to the larger social, cultural, political, economic, and structural forces at work in health. As health-care practitioners and researchers focused on biological, physiological, disease and therapeutic processes, sociocultural, political, and economic conditions are often peripheral or ignored in day-to-day clinical work. However, it is within these latter processes that both health-care practices and patient lives are entrenched. Qualitative researchers are particularly adept at identifying the structural conditions such as the social, cultural, political, local, and economic conditions which contribute to health care and experiences of disease and illness.

For example, the decision to delay treatment by a patient may be understood as an irrational choice impacting his/her chances of survival, but the same may be a result of the patient treating their child's education as a financial priority over his/her own health. While this appears as an “emotional” choice, qualitative researchers try to understand the social and cultural factors that structure, inform, and justify such choices. Rather than assuming that it is an irrational choice, qualitative researchers try to understand the norms and logical grounds on which the patient is making this decision. By foregrounding such logics, stories, fears, and desires, qualitative research expands our analytic precision in learning about complex social worlds, recognizing reasons for medical successes and failures, and interrogating our assumptions about human behavior. These in turn can prove useful in arriving at conclusive, actionable findings which can inform institutional and public health policies and have a very important role to play in any change and transformation we may wish to bring to the societies in which we work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- 1. Shapin S, Schaffer S. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1985. Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Uberoi JP. Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1978. Science and Culture. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Poovey M. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998. A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences of Wealth and Society. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Creswell JW. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bhangu S, Bisshop A, Engelmann S, Meulemans G, Reinert H, Thibault-Picazo Y. Feeling/Following: Creative Experiments and Material Play, Anthropocene Curriculum, Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Max Planck Institute for the History of Science; The Anthropocene Issue. 2016 [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (583.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Science, Tech, Math ›

- Social Sciences ›

- Sociology ›

- Research, Samples, and Statistics ›

An Overview of Qualitative Research Methods

Direct Observation, Interviews, Participation, Immersion, Focus Groups

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

Qualitative research is a type of social science research that collects and works with non-numerical data and that seeks to interpret meaning from these data that help understand social life through the study of targeted populations or places.

People often frame it in opposition to quantitative research , which uses numerical data to identify large-scale trends and employs statistical operations to determine causal and correlative relationships between variables.

Within sociology, qualitative research is typically focused on the micro-level of social interaction that composes everyday life, whereas quantitative research typically focuses on macro-level trends and phenomena.

Key Takeaways

Methods of qualitative research include:

- observation and immersion

- open-ended surveys

- focus groups

- content analysis of visual and textual materials

- oral history

Qualitative research has a long history in sociology and has been used within it for as long as the field has existed.

This type of research has long appealed to social scientists because it allows the researchers to investigate the meanings people attribute to their behavior, actions, and interactions with others.

While quantitative research is useful for identifying relationships between variables, like, for example, the connection between poverty and racial hate, it is qualitative research that can illuminate why this connection exists by going directly to the source—the people themselves.

Qualitative research is designed to reveal the meaning that informs the action or outcomes that are typically measured by quantitative research. So qualitative researchers investigate meanings, interpretations, symbols, and the processes and relations of social life.

What this type of research produces is descriptive data that the researcher must then interpret using rigorous and systematic methods of transcribing, coding, and analysis of trends and themes.

Because its focus is everyday life and people's experiences, qualitative research lends itself well to creating new theories using the inductive method , which can then be tested with further research.

Qualitative researchers use their own eyes, ears, and intelligence to collect in-depth perceptions and descriptions of targeted populations, places, and events.

Their findings are collected through a variety of methods, and often a researcher will use at least two or several of the following while conducting a qualitative study:

- Direct observation : With direct observation, a researcher studies people as they go about their daily lives without participating or interfering. This type of research is often unknown to those under study, and as such, must be conducted in public settings where people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy. For example, a researcher might observe the ways in which strangers interact in public as they gather to watch a street performer.

- Open-ended surveys : While many surveys are designed to generate quantitative data, many are also designed with open-ended questions that allow for the generation and analysis of qualitative data. For example, a survey might be used to investigate not just which political candidates voters chose, but why they chose them, in their own words.

- Focus group : In a focus group, a researcher engages a small group of participants in a conversation designed to generate data relevant to the research question. Focus groups can contain anywhere from 5 to 15 participants. Social scientists often use them in studies that examine an event or trend that occurs within a specific community. They are common in market research, too.

- In-depth interviews : Researchers conduct in-depth interviews by speaking with participants in a one-on-one setting. Sometimes a researcher approaches the interview with a predetermined list of questions or topics for discussion but allows the conversation to evolve based on how the participant responds. Other times, the researcher has identified certain topics of interest but does not have a formal guide for the conversation, but allows the participant to guide it.

- Oral history : The oral history method is used to create a historical account of an event, group, or community, and typically involves a series of in-depth interviews conducted with one or multiple participants over an extended period.

- Participant observation : This method is similar to observation, however with this one, the researcher also participates in the action or events to not only observe others but to gain the first-hand experience in the setting.

- Ethnographic observation : Ethnographic observation is the most intensive and in-depth observational method. Originating in anthropology, with this method, a researcher fully immerses themselves into the research setting and lives among the participants as one of them for anywhere from months to years. By doing this, the researcher attempts to experience day-to-day existence from the viewpoints of those studied to develop in-depth and long-term accounts of the community, events, or trends under observation.

- Content analysis : This method is used by sociologists to analyze social life by interpreting words and images from documents, film, art, music, and other cultural products and media. The researchers look at how the words and images are used, and the context in which they are used to draw inferences about the underlying culture. Content analysis of digital material, especially that generated by social media users, has become a popular technique within the social sciences.

While much of the data generated by qualitative research is coded and analyzed using just the researcher's eyes and brain, the use of computer software to do these processes is increasingly popular within the social sciences.

Such software analysis works well when the data is too large for humans to handle, though the lack of a human interpreter is a common criticism of the use of computer software.

Pros and Cons

Qualitative research has both benefits and drawbacks.

On the plus side, it creates an in-depth understanding of the attitudes, behaviors, interactions, events, and social processes that comprise everyday life. In doing so, it helps social scientists understand how everyday life is influenced by society-wide things like social structure , social order , and all kinds of social forces.

This set of methods also has the benefit of being flexible and easily adaptable to changes in the research environment and can be conducted with minimal cost in many cases.

Among the downsides of qualitative research is that its scope is fairly limited so its findings are not always widely able to be generalized.

Researchers also have to use caution with these methods to ensure that they do not influence the data in ways that significantly change it and that they do not bring undue personal bias to their interpretation of the findings.

Fortunately, qualitative researchers receive rigorous training designed to eliminate or reduce these types of research bias.

- How to Conduct a Sociology Research Interview

- What Is Participant Observation Research?

- Immersion Definition: Cultural, Language, and Virtual

- Definition and Overview of Grounded Theory

- The Differences Between Indexes and Scales

- Pros and Cons of Secondary Data Analysis

- Social Surveys: Questionnaires, Interviews, and Telephone Polls

- The Different Types of Sampling Designs in Sociology

- Principal Components and Factor Analysis

- Sociology Explains Why Some People Cheat on Their Spouses

- Deductive Versus Inductive Reasoning

- How to Construct an Index for Research

- Data Sources For Sociological Research

- A Review of Software Tools for Quantitative Data Analysis

- Constructing a Deductive Theory

- Scales Used in Social Science Research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Research Methodology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics and Religion

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 Introduction

Patricia Leavy Independent Scholar Kennebunk, ME, USA

- Published: 01 July 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter serves as the introduction to the Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research . The first half of the chapter responds to two questions. First, the chapter addresses the question: What is qualitative research? In answering the question, the chapter reviews the major elements of research: paradigm, ontology, epistemology (which together form the philosophical basis of research), genre, methods, theory, methodology (which operate at the level of praxis), ethics, values, and reflexivity (which merge the philosophical and praxis dimensions of research). Second, the chapter addresses the question: Who are qualitative researchers? Leavy explains qualitative research as a form of bricolage and qualitative researchers as bricoleurs. The remainder of the chapter reviews the contents of the handbook, providing a chapter by chapter summary.

We shall not cease from exploration and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time. – T. S. Eliot

I open the introduction to the Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research with the preceding quote for two reasons. First, it captures the essence of qualitative inquiry as a way of understanding, describing, explaining, unraveling, illuminating, chronicling, and documenting social life—which includes attention to the everyday, to the mundane and ordinary, as much as the extraordinary. Qualitative research can involve the study of others, but also the self and the complex relationships between, within, and among people and groups, including our own entanglements. The second reason I have begun with this quote is because it opens Laurel Richardson’s book Fields of Play: Constructing an Academic Life (1997) . This is one of my favorite books, and, in it, Richardson expands the way we think of ourselves as researchers, writers, and knowers. What I intend to do by way of sharing this is to locate myself within the field and within this text—this is something that many qualitative researchers aim to do, in various ways. In qualitative research, we are not outside of our projects, but located and shifting within them. Qualitative research is an engaged way of building knowledge about the social world and human experience, and qualitative researchers are enmeshed in their projects.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Science is a conversation between rigor and imagination. ( Abbott, 2004 , p. 3)

Qualitative research is a way of learning about social reality. Qualitative approaches to research can be used across the disciplines to study a wide array of topics. In the social and behavioral sciences, these approaches to research are often used to explore, describe, or explain social phenomenon; unpack the meanings people ascribe to activities, situations, events, or artefacts; build a depth of understanding about some aspect of social life; build “thick descriptions” (see Clifford Geertz, 1973 ) of people in naturalistic settings; explore new or underresearched areas; or make micro–macro links (illuminate connections between individuals–groups and institutional and/or cultural contexts).

Qualitative research itself is an umbrella term for a rich array of research practices and products. Qualitative research is an expansive and continually evolving methodological field that encompasses a wide range of approaches to research, as well as multiple perspectives on the nature of research itself. It has been argued that qualitative research developed in an interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, or counterdisciplinary field ( Denzin & Lincoln, 1998 ; Jovanic, 2011 ; Lorenz, 2010 ). This approach to inquiry is unique, in part because of its philosophical and methodological diversity, as well as because of the value system guiding research practice.

The diversity of the qualitative landscape, as well as the gestalt of qualitative practice, is also partly attributable to the context in which qualitative research developed. Chapter 2 in this handbook looks much more fully at the historical development of qualitative research, but I would like to briefly note the period of growth in the 1960s and 1970s because it bears directly on the richness of contemporary qualitative practice. 2

Although there were many pivotal works published prior to the 1960s, the social justice movements of the 1960s and 1970s—the civil rights, women’s, gay rights, and peace movements—culminated in major changes in the academic landscape, including the asking of new research questions and the reframing of many previously asked research questions and corresponding approaches to research. These movements in essence became sites for new ways of thinking and led to the critique of dominant methods of scientific practice, many of which relied on positivism ( Jovanic, 2011 ). There was a drive to include people historically excluded from social research or included in ways that reinforced stereotypes and justified relations of oppression, and researchers became more cognizant of power within the research process ( Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2011 ). A couple of decades later, interdisciplinary area studies that developed in the context of critique—women’s studies, African-American studies, Chicana/Chicano studies—began emerging across academic institutions.

Because of the sociohistorical conditions in which it developed, the qualitative tradition can be characterized by its multiplicity of approaches to research as well as by its focus on the uses to which that research might be put . In this vein, there is a social justice undercurrent to qualitative practice, one that may be implicit or explicit depending on the positioning and goals of the practitioner and the project at hand.

Many qualitative researchers define qualitative research by comparing it to quantitative research. I myself have done this. However, instead of describing what something is by explaining what it isn’t, I focus on a discussion of the qualitative tradition as understood on its own merits. 3 One way of understanding qualitative research is by considering the key dimensions of any research practice and discussing them in terms of qualitative practice.

The Elements of Research

The main dimensions of research can be categorized under three general categories: philosophical, praxis, and ethics. The philosophical substructure of research consists of three elements: paradigm, ontology, and epistemology. At the level of praxis there are four key elements of research: genre, methods, theory, and methodology. The ethical compass (which combines philosophical and praxis dimensions) includes three main elements: ethics, values, and reflexivity (see Table 1.1 ).

The Philosophical Substructure of Qualitative Research

A range of beliefs guide research practice—beliefs about how research should proceed, what can be known, who can be a knower, and how we come to know. Together, these beliefs form the philosophical substructure of research and inform all aspects of the research from topic selection to research design to the final representation and dissemination of the research findings and all phases in between.

A paradigm is a worldview through which knowledge is filtered ( Kuhn, 1962 ). In other words, it is an overarching perspective that guides the research process. I think of paradigms as sunglasses, with different color lenses. When you put a pair on, it influences everything you see. Qualitative research is multiparadigmatic, with researchers working from different worldviews (such as post-positivism, interpretivism, and critical orientations), which makes it a highly diverse field of inquiry.

An ontology is a philosophical belief system about the nature of social reality, including what we can learn about this reality and how we can do so. In their classic definition, Egon Guba and Yvonna Lincoln explained the ontological question as: “What is the form and nature of reality and, therefore, what is there that can be known about it?” (1998, p. 201). Qualitative researchers adopt a perspective that suggests knowledge building is viewed as generative and process-oriented. The truth is not absolute and ready to be “discovered” by “objective” researchers, but rather it is contingent, contextual, and multiple ( Saldaña, 2011 ). Subjectivity is acknowledged and valued. Objectivity may be redefined and achieved through the owning and disclosing of one’s values system, not disavowing it ( Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2011 ).

If the ontological question is “What can be known?” then the epistemological question is “Who can be a knower?” An epistemology is a philosophical belief system about how research proceeds as an embodied activity, how one embodies the role of researcher, and the relationship between the researcher and research participants ( Guba & Lincoln, 1998 ; Harding, 1987 ; Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2004 ; 2011 ). Qualitative researchers work from many different epistemological positions. Researchers may work individually or as a part of a team with their participants in the co-creation of knowledge. From this perspective, researchers are not considered neutral or objective in the traditional sense. Rather, researchers acknowledge how their personal, professional, and political commitments influence all aspects of their research. Researchers are considered instruments in qualitative research ( Bresler, 2005 ; Saldaña, 2011 ). Research participants are valued and positioned as knowledge bearers and co-creators. This position rejects a hierarchical structure between the researcher and research participants or the idea that the researcher is the sole authority.

Together, the ontological and epistemological belief systems guiding the research practice serves as the philosophical basis or substructure of any research practice ( Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2011 ). Although a researcher’s ontological and epistemological positions can vary across qualitative projects and may be influenced by a range of other factors, including theoretical and personal commitments, generally, qualitative researchers seek to build partial and contextualized truths in collaboration with their research participants or through reflexive engagement with their research texts.

Praxis: Approaches, Methods, and Theories in Action

Praxis is the doing of research—the practice of research. Approaches, methods, and theories come into being during praxis, as researchers build projects and execute on them, often making adjustments along the way.

Genres of research are overarching categories for different ways of approaching research ( Saldaña, 2011 ). Each genre lends itself to studying particular kinds of topics and includes a range of commonly used methods of data collection, analysis, and representation. Frequently used research genres include but are not limited to field research, interview, grounded theory, unobtrusive approaches, participatory research, community-based research, arts-based research, internet research, and multimethod and mixed-method approaches. This is not an exhaustive list. The genre within which a researcher works is motivated by a combination of factors, including the research topic, the research question(s), his or her methodological preferences and experiences, and the intended audience(s) for the research, as well as by a range of pragmatic considerations such as funding, time, and the researcher’s previous experience, skills, and personal preferences.

Research methods are tools for data collection. Research methods commonly used in qualitative practice include but are not limited to ethnography, autoethnography, duoethnography, narrative inquiry, in-depth interview, semistructured interview, focus group interview, oral history, document analysis, content analysis, historical-comparative methods, poetic inquiry, audiovisual methods, visual methods, photo-voice, case study, multiple case study, discourse analysis, conversation analysis, daily diary research, program evaluation, ethnodrama, ethnotheatre, ethnocinema, play building, and fiction-based research. As you can see, qualitative researchers use a range of tools for data collection. Research methods are selected because they are the best tools to gather the data sought for a particular study. The selection of research methods should be made in conjunction with the research question(s) and purpose or objective. In other words, depending on the research topic and how the research questions are framed, as well as more pragmatic issues such as access to participants or textual/preexisting data sources, time, and practical skills, researchers are guided to particular methods.

Each genre discussed earlier lends itself to the use of particular methods. For example, the genre of arts-based research lends itself to the use of ethnodrama, ethnotheatre, ethnocinema, play building, fiction-based research, poetic inquiry, audiovisual methods, photo-voice, or visual methods. The genre of interview research lends itself to the use of in-depth interview, semistructured interview, focus group interview, or oral history. Of course, these genres are all more complicated in practice. For example, discourse analysis is a method that may be employed in an interview study, document analysis, or narrative inquiry. Furthermore, depending on the context in which one employs a method, such as narrative inquiry, one might view it as an arts-based approach, interview approach, way of doing autoethnography, or a method of analysis. The intent is not to confuse matters but, given how large and diffuse the field of qualitative research is and the variety of ways that methods can be creatively employed, it is important to understand that you may come across these terms conceptualized in various ways in the literature. One of the reasons that methods can be conceptualized and employed in many different ways is because qualitative researchers also draw on multiple theories.

A theory is an account of social reality that is grounded in empirical data but extends beyond that data. Numerous theoretical perspectives may guide the research process, including but not limited to post-positivism, interpretive, symbolic interactionism, dramaturgy, phenomenology, ethnomethodology, social constructionism, post-structuralism, post-modernism, feminism, intersectionality theory, queer theory, and critical race theory. This is also not an exhaustive list and in most instances each of these theoretical perspectives are general categories for a range of more specific theories. A qualitative research study may also yield the development of a new theory. In these instances, theory develops inductively out of the research process. In other words, the study generates data out of which a theory is built—that theory is grounded in the empirical data from that study but extends beyond that data and can be applied to other situations.

A methodology is plan for how research will proceed—combining methods and theory. The methodology is what the researcher actually does once he or she has combined the different elements of research. The methodology is informed by the philosophical beliefs guiding the research, the selection of research methods, and the use of theory. One’s attention to ethics and their corresponding values system also influences how a study is designed and how methods are employed. Although two studies may use the same research method—for instance, a focus group interview—the researchers’ methodologies may be completely different. In other words, how they proceed with the research, based not only on their data collection tool but also on how they conceive of the use of that tool and thus structure the study, determines their methodology. The level of moderation and/or control a researcher exhibits during focus group interviews can vary greatly. Methodologies are not standardized nor are they typically etched in stone. Not only will methodological approaches to research vary across projects, but, even within a particular project, methodologies are often viewed as flexible and malleable. A qualitative researcher might adjust his or her methodology over the course of a project to facilitate new learning or new insights or to adapt to unanticipated challenges, obstacles, or opportunities. The malleability of qualitative methodologies is a strength of this approach to knowledge generation.

It is important to note that although I have reviewed methods for data collection as a part of methodology, there are also methods or strategies for qualitative data analysis, interpretation, representation, and dissemination of research findings. Similar to data collection tools and theories, these too are diverse, making the methodological possibilities rich.

Ethics: Beliefs and Practices

Ethics is an area that bridges the philosophical and praxis aspects of research. Ethics play a central role in any research practice. Typically, when we think about ethics in social research, particularly when working with human subjects, we are referring to issues such as preventing harm to the people or settings involved in the study, avoiding exploitation of research participants (with added attention in the case of vulnerable populations), disclosure of the nature of the study and how the findings will be used, the voluntary nature of participation, and confidentiality. Additionally, qualitative researchers have an ethical obligation to carefully consider how research participants are portrayed and to act sensitively.

Additional ethical issues are linked to a researcher’s ontological, epistemological, and practical imperatives, which together form a researcher’s values system. For instance, the real-world value or public usefulness of the research, the inclusion of underrepresented populations, the treatment of anomalous or contradictory data, and the way that the research findings are distributed to relevant stakeholders—these issues are also connected to ethical practice.

Reflexivity is also a core concept in the qualitative community and refers to one’s attention to how power and bias come to bear during all phases of the research. As D. Soyini Madison suggests, reflexivity is about “the politics of positionality” and acknowledging our power, privileges, and biases throughout the research process (2005, p. 6). The social justice imperative of many qualitative projects is a driver of reflexivity, as are critical and power-sensitive theoretical traditions. I suggest reflexivity is both a philosophical perspective and a way of doing or acting within the context of research, from start to finish (see Table 1.2 ).

Given the wide range of approaches, tools, and values that guide qualitative research, it is a rich and evolving tradition with innumerable possibilities for knowledge building and knowledge sharing. Researchers can build, craft, or construct many different kinds of projects to study a nearly limitless range of topics. For these reasons, many consider qualitative research a craft or form of bricolage.

Who Are Qualitative Researchers?

We are all interpretive bricoleurs stuck in the present working against the past as we move into a politically charged and challenging future. ( Norman K. Denzin, 2010 , p. 15)

The qualitative researcher can be thought of as a bricoleur—someone who comfortably draws on multiple bodies of scholarship, methods, and theories to do her or his work. The term bricoleur is attributed to Levi-Strauss (1966) ; however, Denzin and Lincoln popularized applying the term to the work of qualitative researchers. Thomas A. Schwandt (2001) writes:

As a bricoleur , the qualitative inquirer is capable of donning multiple identities—researcher, scientist, artist, critic, and performer—and engaging in different kinds of bricolage that consist of particular configurations of (or ways of relating) various fragments of inherited methodologies, methods, empirical materials, perspectives, understandings, ways of presentation, situated responsiveness, and so on into a coherent, reasoned approach to a research situation and problem. The bricolage appears to vary depending on one’s allegiance to different notions of interpretation, understanding, representation, and so on drawn from various intellectual and practice traditions. (p. 20) Table 1.2 Open in new tab Summary of key elements of research Element . Philosophical or Praxis . Definition . Paradigm Philosophical Guiding worldview Ontology Philosophical The nature of social reality and what can be known about it Epistemology Philosophical The role of the researcher and researcher/participant relationship Genres Praxis Categories of ways of approaching research Methods Praxis Tools for data collection Theory Praxis Account of social reality that extends beyond data Methodology Praxis A plan for how research will proceed (combining methods, theory, and ethics) Ethics Philosophical and Praxis How one engages with, informs, and protects participants Values System Philosophical and Praxis Usefulness and distribution to the public, inclusion of underrepresented groups Reflexivity Philosophical and Praxis Attention to power, bias, and researcher positionality Element . Philosophical or Praxis . Definition . Paradigm Philosophical Guiding worldview Ontology Philosophical The nature of social reality and what can be known about it Epistemology Philosophical The role of the researcher and researcher/participant relationship Genres Praxis Categories of ways of approaching research Methods Praxis Tools for data collection Theory Praxis Account of social reality that extends beyond data Methodology Praxis A plan for how research will proceed (combining methods, theory, and ethics) Ethics Philosophical and Praxis How one engages with, informs, and protects participants Values System Philosophical and Praxis Usefulness and distribution to the public, inclusion of underrepresented groups Reflexivity Philosophical and Praxis Attention to power, bias, and researcher positionality

Qualitative researchers may draw on scientific, humanistic, artistic, and other disciplinary forms. In this regard, qualitative research can be viewed as a scholarly, practical, and creative pursuit. Researchers need to be able to think analytically, symbolically, imaginatively, and metaphorically ( Saldaña, 2011 ). Moreover, projects often demand innovation, creativity, intuition, flexibility, and responsiveness (adapting to new learning or practical problems). This is a rigorous and often labor-intensive process. Qualitative research commonly requires working with others over an expanse of time and producing large amounts of data for analysis while also demanding sustained attention to ethics and values. It is also a creative process—allowing researchers to experiment, play, adapt, learn, and grow along the way.

Of course, pragmatic considerations come into play when designing a project: funding, time, access to needed participants or textual/preexisting data sources, and the researcher’s previous experience, skills, and personal preferences. Unfortunately, qualitative researchers are more often limited by practical issues than by their imaginative capabilities.

Despite these challenges, qualitative research is also a deeply rewarding process that may result in new learning about topics of import, increased self-awareness, the forging of meaningful relationships between co-creators of knowledge, the production of public scholarship, and the impetus for social change.

The Contents of This Handbook

As noted in the preface, no handbook can be all things to all people. It’s impossible to cover the entire field, and so I have approached the content with practicality in mind: what one learning about and/or embarking on qualitative research most needs to know, peppered with advanced material and prospective reviews intended to be of value to even the most experienced researchers.

Part 1 of this handbook, “The Qualitative Tradition,” offers a historical review of the field. Specifically, Part 1 presents an overview of the history of qualitative research in the social sciences and the ethical substructure of qualitative research practice.

In Chapter 2 , “Historical Overview of Qualitative Research in the Social Sciences,” Svend Brinkmann, Michael Hviid Jacobsen, and Søren Kristiansen provide a detailed history of qualitative research in the social sciences. As they note, this history is a complicated task because there is no agreed-upon version but rather a variety of perspectives. Accordingly, these authors present six histories of qualitative research: the conceptual history, the internal history, the marginalizing history, the repressed history, the social history, and the technological history. They also suggest that writing about history is necessarily tied up with writing about the future and thus conclude their contribution with a vision of the field. In Chapter 3 , “The History of Historical-Comparative Methods in Sociology,” Chares Demetriou and Victor Roudometof present an overview of the historical trajectory of comparative-historical sociology while considering the development of specific methodological approaches. Next is Anna Traianou’s chapter, “The Centrality of Ethics in Qualitative Research.” Attention to the ethical substructure of research is central to any qualitative practice and thus is given priority as the closing chapter in Part 1 . Traianou details the main ethical issues in qualitative practice, bearing in mind the changing sociohistorical climate in which research is carried out.

Part 2 of this handbook, “Approaches to Qualitative Research,” presents an array of philosophical approaches to qualitative research (all of which have implications for research praxis). Because qualitative research is a diverse tradition, it is impossible to adequately cover all of the approaches researchers may adopt. Nevertheless, Part 2 provides both an overview of the key approaches to qualitative research and detailed reviews of several commonly used approaches.

Part 2 opens with Renée Spencer, Julia M. Pryce, and Jill Walsh’s chapter, “Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research,” which provides a general view of the philosophical approaches that typically guide qualitative practice. They review post-positivism, constructivism, critical theory, feminism, and queer theory and offer a brief history of these approaches, considering the ontological, epistemological, and axiological assumptions on which they rest, and they detail some of their distinguishing features. They also identify three overarching, interrelated, and contested issues with which the field is being confronted: retaining the rich diversity that has defined the field, the articulation of recognizable standards for qualitative research, and the commensurability of differing approaches.

After the overview in Chapter 5 , we turn to in-depth treatments of specific approaches to qualitative research. In Chapter 6 , “Applied Interpretive Approaches,” Sally E. Thorne turns to the applied world of qualitative practice. Thorne considers how many applied scholars have been departing from established method to articulate approaches better suited to the questions of the applied world. This chapter considers the evolving relationship between the methods and their disciplinary origins and current trends in the direction of the applied interpretive qualitative project. Interpretive description is used as a methodological case in point to illustrate the kinds of departures that applied approaches are taking from their theoretical roots as they begin to advance knowledge development within applied contexts.

Chapter 7 , “The Grounded Theory Method” by Antony Bryant, reviews grounded theory, which, as Bryant notes, is itself a somewhat misleading term because it actually refers to a method that facilitates the development of new theoretical insights. Bryant’s suggestion about the complexity of the term itself is duly noted because this chapter could easily have been placed in Part 3 of this handbook. However, because grounded theory can be used in conjunction with more than one method of data collection, I have placed it in Part 2 as an approach to research. This chapter provides background information about the development of grounded theory as well as its main features, procedures outputs, and evaluation criteria.

The final three chapters in Part 2 tackle power-sensitive or social justice approaches to qualitative research that have emerged in the context of activist and scholarly work. In Chapter 8 , “Feminist Qualitative Research: Toward Transformation of Science and Society,” Maureen C. McHugh offers an in-depth treatment of feminist qualitative research, described in terms of its purposes of addressing women’s lives, advocacy for women, analysis of gender oppression, and transformation of society. The chapter covers topics including the feminist critiques of social science research, the transformation of science from empiricism to post-modernism (including intersectionality and double consciousness), reflexivity, collaboration, power analysis, advocacy, validity, and voice. Several qualitative approaches to research are described in relation to feminist research goals, with illustrations of feminist research. In Chapter 9 , “Critical Approaches to Qualitative Research,” Kum-Kum Bhavnani, Peter Chua, and Dana Collins reflect on critical strategies in qualitative research and examine the meanings and debates associated with the term “critical.” The authors contrast liberal and dialectical notions and practices in relations to social analysis and qualitative research. The chapter also explores how critical social research may be synonymous with critical ethnography in relation to issues of power, positionality, representation, and the production of situated knowledges. It uses Bhavnani’s (1993) framework to draw on Dana Collin’s research as a specific case to suggest how the notion of the “critical” relates to ethnographic research practices: ensuring feminist and queer accountability, resisting reinscription, and integrating lived experience. In Chapter 10 , “Decolonizing Research Practice: Indigenous Methodologies, Aboriginal Methods, and Knowledge/Knowing,” Mike Evans, Adrian Miller, Peter Hutchinson, and Carlene Dingwall review Indigenous approaches to research that are fundamentally rooted in the traditions and knowledge systems of Indigenous peoples themselves. The authors suggest Indigenous methodologies and methods have become both systems for generating knowledge and ways of responding to the processes of colonization. They describe two approaches drawn from the work of two Indigenous scholars with their communities in Australia and Canada. They hope this work leads not only to better, more pertinent research that is well disseminated but also to improvement in the situations of Indigenous communities and peoples.

The third section of this handbook, “Narrative Inquiry, Field Research, and Interview Methods,” provides chapters on a range of methods for collecting data directly from people (groups or individuals) or by systematically observing people engaged in activities in natural settings.