- Open access

- Published: 03 September 2022

A literature review of risk, regulation, and profitability of banks using a scientometric study

- Shailesh Rastogi 1 ,

- Arpita Sharma 1 ,

- Geetanjali Pinto 2 &

- Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9757-1904 1 , 3

Future Business Journal volume 8 , Article number: 28 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

This study presents a systematic literature review of regulation, profitability, and risk in the banking industry and explores the relationship between them. It proposes a policy initiative using a model that offers guidelines to establish the right mix among these variables. This is a systematic literature review study. Firstly, the necessary data are extracted using the relevant keywords from the Scopus database. The initial search results are then narrowed down, and the refined results are stored in a file. This file is finally used for data analysis. Data analysis is done using scientometrics tools, such as Table2net and Sciences cape software, and Gephi to conduct network, citation analysis, and page rank analysis. Additionally, content analysis of the relevant literature is done to construct a theoretical framework. The study identifies the prominent authors, keywords, and journals that researchers can use to understand the publication pattern in banking and the link between bank regulation, performance, and risk. It also finds that concentration banking, market power, large banks, and less competition significantly affect banks’ financial stability, profitability, and risk. Ownership structure and its impact on the performance of banks need to be investigated but have been inadequately explored in this study. This is an organized literature review exploring the relationship between regulation and bank performance. The limitations of the regulations and the importance of concentration banking are part of the findings.

Introduction

Globally, banks are under extreme pressure to enhance their performance and risk management. The financial industry still recalls the ignoble 2008 World Financial Crisis (WFC) as the worst economic disaster after the Great Depression of 1929. The regulatory mechanism before 2008 (mainly Basel II) was strongly criticized for its failure to address banks’ risks [ 47 , 87 ]. Thus, it is essential to investigate the regulation of banks [ 75 ]. This study systematically reviews the relevant literature on banks’ performance and risk management and proposes a probable solution.

Issues of performance and risk management of banks

Banks have always been hailed as engines of economic growth and have been the axis of the development of financial systems [ 70 , 85 ]. A vital parameter of a bank’s financial health is the volume of its non-performing assets (NPAs) on its balance sheet. NPAs are advances that delay in payment of interest or principal beyond a few quarters [ 108 , 118 ]. According to Ghosh [ 51 ], NPAs negatively affect the liquidity and profitability of banks, thus affecting credit growth and leading to financial instability in the economy. Hence, healthy banks translate into a healthy economy.

Despite regulations, such as high capital buffers and liquidity ratio requirements, during the second decade of the twenty-first century, the Indian banking sector still witnessed a substantial increase in NPAs. A recent report by the Indian central bank indicates that the gross NPA ratio reached an all-time peak of 11% in March 2018 and 12.2% in March 2019 [ 49 ]. Basel II has been criticized for several reasons [ 98 ]. Schwerter [ 116 ] and Pakravan [ 98 ] highlighted the systemic risk and gaps in Basel II, which could not address the systemic risk of WFC 2008. Basel III was designed to close the gaps in Basel II. However, Schwerter [ 116 ] criticized Basel III and suggested that more focus should have been on active risk management practices to avoid any impending financial crisis. Basel III was proposed to solve these issues, but it could not [ 3 , 116 ]. Samitas and Polyzos [ 113 ] found that Basel III had made banking challenging since it had reduced liquidity and failed to shield the contagion effect. Therefore, exploring some solutions to establish the right balance between regulation, performance, and risk management of banks is vital.

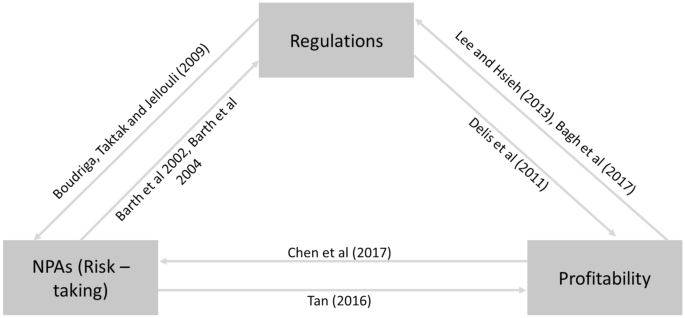

Keeley [ 67 ] introduced the idea of a balance among banks’ profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking). This study presents the balancing act of profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking) of banks as a probable solution to the issues of bank performance and risk management and calls it a triad . Figure 1 illustrates the concept of a triad. Several authors have discussed the triad in parts [ 32 , 96 , 110 , 112 ]. Triad was empirically tested in different countries by Agoraki et al. [ 1 ]. Though the idea of a triad is quite old, it is relevant in the current scenario. The spirit of the triad strongly and collectively admonishes the Basel Accord and exhibits new and exhaustive measures to take up and solve the issue of performance and risk management in banks [ 16 , 98 ]. The 2008 WFC may have caused an imbalance among profitability, regulation, and risk-taking of banks [ 57 ]. Less regulation , more competition (less profitability ), and incentive to take the risk were the cornerstones of the 2008 WFC [ 56 ]. Achieving a balance among the three elements of a triad is a real challenge for banks’ performance and risk management, which this study addresses.

Triad of Profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking). Note The triad [ 131 ] of profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking) is shown in Fig. 1

Triki et al. [ 130 ] revealed that a bank’s performance is a trade-off between the elements of the triad. Reduction in competition increases the profitability of banks. However, in the long run, reduction in competition leads to either the success or failure of banks. Flexible but well-expressed regulation and less competition add value to a bank’s performance. The current review paper is an attempt to explore the literature on this triad of bank performance, regulation, and risk management. This paper has the following objectives:

To systematically explore the existing literature on the triad: performance, regulation, and risk management of banks; and

To propose a model for effective bank performance and risk management of banks.

Literature is replete with discussion across the world on the triad. However, there is a lack of acceptance of the triad as a solution to the woes of bank performance and risk management. Therefore, the findings of the current papers significantly contribute to this regard. This paper collates all the previous studies on the triad systematically and presents a curated view to facilitate the policy makers and stakeholders to make more informed decisions on the issue of bank performance and risk management. This paper also contributes significantly by proposing a DBS (differential banking system) model to solve the problem of banks (Fig. 7 ). This paper examines studies worldwide and therefore ensures the wider applicability of its findings. Applicability of the DBS model is not only limited to one nation but can also be implemented worldwide. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the publication pattern in banking using a blend of scientometrics analysis tools, network analysis tools, and content analysis to understand the link between bank regulation, performance, and risk.

This paper is divided into five sections. “ Data and research methods ” section discusses the research methodology used for the study. The data analysis for this study is presented in two parts. “ Bibliometric and network analysis ” section presents the results obtained using bibliometric and network analysis tools, followed by “ Content Analysis ” section, which presents the content analysis of the selected literature. “ Discussion of the findings ” section discusses the results and explains the study’s conclusion, followed by limitations and scope for further research.

Data and research methods

A literature review is a systematic, reproducible, and explicit way of identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing relevant research produced and published by researchers [ 50 , 100 ]. Analyzing existing literature helps researchers generate new themes and ideas to justify the contribution made to literature. The knowledge obtained through evidence-based research also improves decision-making leading to better practical implementation in the real corporate world [ 100 , 129 ].

As Kumar et al. [ 77 , 78 ] and Rowley and Slack [ 111 ] recommended conducting an SLR, this study also employs a three-step approach to understand the publication pattern in the banking area and establish a link between bank performance, regulation, and risk.

Determining the appropriate keywords for exploring the data

Many databases such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus are available to extract the relevant data. The quality of a publication is associated with listing a journal in a database. Scopus is a quality database as it has a wider coverage of data [ 100 , 137 ]. Hence, this study uses the Scopus database to extract the relevant data.

For conducting an SLR, there is a need to determine the most appropriate keywords to be used in the database search engine [ 26 ]. Since this study seeks to explore a link between regulation, performance, and risk management of banks, the keywords used were “risk,” “regulation,” “profitability,” “bank,” and “banking.”

Initial search results and limiting criteria

Using the keywords identified in step 1, the search for relevant literature was conducted in December 2020 in the Scopus database. This resulted in the search of 4525 documents from inception till December 2020. Further, we limited our search to include “article” publications only and included subject areas: “Economics, Econometrics and Finance,” “Business, Management and Accounting,” and “Social sciences” only. This resulted in a final search result of 3457 articles. These results were stored in a.csv file which is then used as an input to conduct the SLR.

Data analysis tools and techniques

This study uses bibliometric and network analysis tools to understand the publication pattern in the area of research [ 13 , 48 , 100 , 122 , 129 , 134 ]. Some sub-analyses of network analysis are keyword word, author, citation, and page rank analysis. Author analysis explains the author’s contribution to literature or research collaboration, national and international [ 59 , 99 ]. Citation analysis focuses on many researchers’ most cited research articles [ 100 , 102 , 131 ].

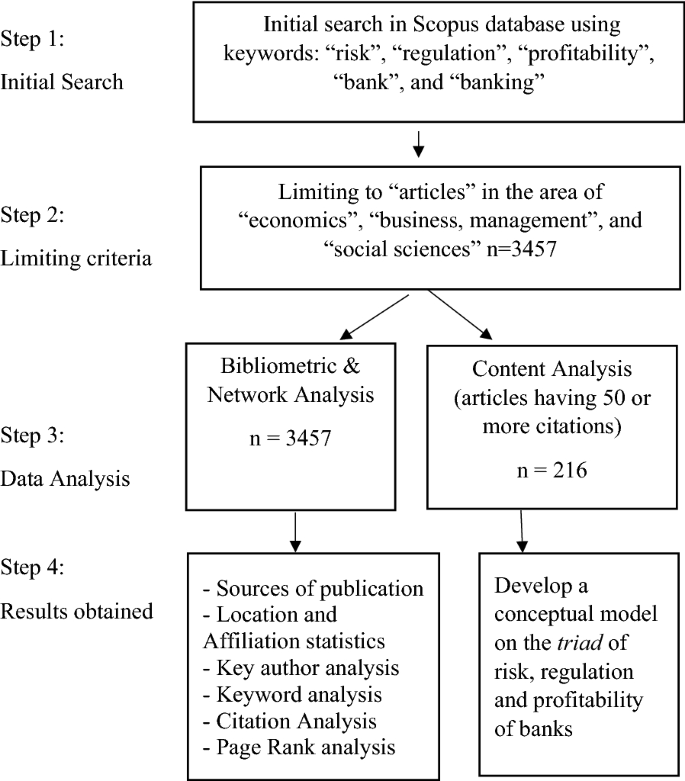

The.csv file consists of all bibliometric data for 3457 articles. Gephi and other scientometrics tools, such as Table2net and ScienceScape software, were used for the network analysis. This.csv file is directly used as an input for this software to obtain network diagrams for better data visualization [ 77 ]. To ensure the study’s quality, the articles with 50 or more citations (216 in number) are selected for content analysis [ 53 , 102 ]. The contents of these 216 articles are analyzed to develop a conceptual model of banks’ triad of risk, regulation, and profitability. Figure 2 explains the data retrieval process for SLR.

Data retrieval process for SLR. Note Stepwise SLR process and corresponding results obtained

Bibliometric and network analysis

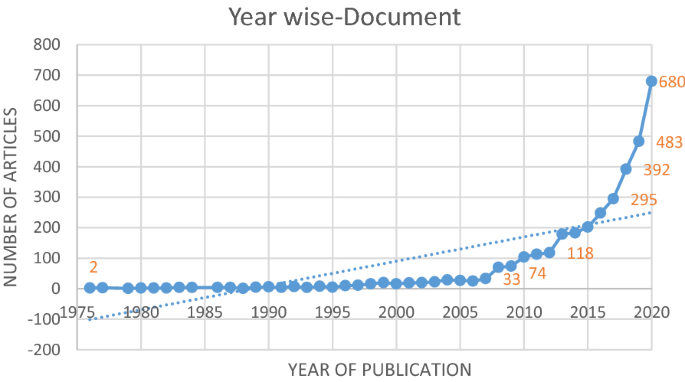

Figure 3 [ 58 ] depicts the total number of studies that have been published on “risk,” “regulation,” “profitability,” “bank,” and “banking.” Figure 3 also depicts the pattern of the quality of the publications from the beginning till 2020. It undoubtedly shows an increasing trend in the number of articles published in the area of the triad: “risk” regulation” and “profitability.” Moreover, out of the 3457 articles published in the said area, 2098 were published recently in the last five years and contribute to 61% of total publications in this area.

Articles published from 1976 till 2020 . Note The graph shows the number of documents published from 1976 till 2020 obtained from the Scopus database

Source of publications

A total of 160 journals have contributed to the publication of 3457 articles extracted from Scopus on the triad of risk, regulation, and profitability. Table 1 shows the top 10 sources of the publications based on the citation measure. Table 1 considers two sets of data. One data set is the universe of 3457 articles, and another is the set of 216 articles used for content analysis along with their corresponding citations. The global citations are considered for the study from the Scopus dataset, and the local citations are considered for the articles in the nodes [ 53 , 135 ]. The top 10 journals with 50 or more citations resulted in 96 articles. This is almost 45% of the literature used for content analysis ( n = 216). Table 1 also shows that the Journal of Banking and Finance is the most prominent in terms of the number of publications and citations. It has 46 articles published, which is about 21% of the literature used for content analysis. Table 1 also shows these core journals’ SCImago Journal Rank indicator and H index. SCImago Journal Rank indicator reflects the impact and prestige of the Journal. This indicator is calculated as the previous three years’ weighted average of the number of citations in the Journal since the year that the article was published. The h index is the number of articles (h) published in a journal and received at least h. The number explains the scientific impact and the scientific productivity of the Journal. Table 1 also explains the time span of the journals covering articles in the area of the triad of risk, regulation, and profitability [ 7 ].

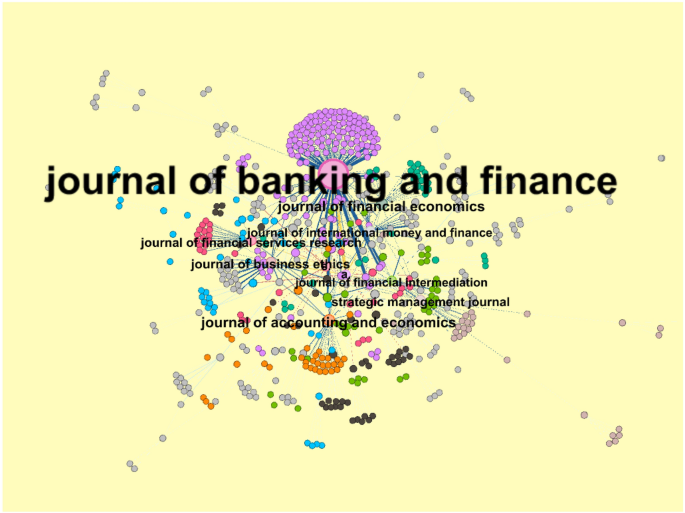

Figure 4 depicts the network analysis, where the connections between the authors and source title (journals) are made. The network has 674 nodes and 911 edges. The network between the author and Journal is classified into 36 modularities. Sections of the graph with dense connections indicate high modularity. A modularity algorithm is a design that measures how strong the divided networks are grouped into modules; this means how well the nodes are connected through a denser route relative to other networks.

Network analysis between authors and journals. Note A node size explains the more linked authors to a journal

The size of the nodes is based on the rank of the degree. The degree explains the number of connections or edges linked to a node. In the current graph, a node represents the name of the Journal and authors; they are connected through the edges. Therefore, the more the authors are associated with the Journal, the higher the degree. The algorithm used for the layout is Yifan Hu’s.

Many authors are associated with the Journal of Banking and Finance, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Financial Economics, Journal of Financial Services Research, and Journal of Business Ethics. Therefore, they are the most relevant journals on banks’ risk, regulation, and profitability.

Location and affiliation analysis

Affiliation analysis helps to identify the top contributing countries and universities. Figure 5 shows the countries across the globe where articles have been published in the triad. The size of the circle in the map indicates the number of articles published in that country. Table 2 provides the details of the top contributing organizations.

Location of articles published on Triad of profitability, regulation, and risk

Figure 5 shows that the most significant number of articles is published in the USA, followed by the UK. Malaysia and China have also contributed many articles in this area. Table 2 shows that the top contributing universities are also from Malaysia, the UK, and the USA.

Key author analysis

Table 3 shows the number of articles written by the authors out of the 3457 articles. The table also shows the top 10 authors of bank risk, regulation, and profitability.

Fadzlan Sufian, affiliated with the Universiti Islam Malaysia, has the maximum number, with 33 articles. Philip Molyneux and M. Kabir Hassan are from the University of Sharjah and the University of New Orleans, respectively; they contributed significantly, with 20 and 18 articles, respectively.

However, when the quality of the article is selected based on 50 or more citations, Fadzlan Sufian has only 3 articles with more than 50 citations. At the same time, Philip Molyneux and Allen Berger contributed more quality articles, with 8 and 11 articles, respectively.

Keyword analysis

Table 4 shows the keyword analysis (times they appeared in the articles). The top 10 keywords are listed in Table 4 . Banking and banks appeared 324 and 194 times, respectively, which forms the scope of this study, covering articles from the beginning till 2020. The keyword analysis helps to determine the factors affecting banks, such as profitability (244), efficiency (129), performance (107, corporate governance (153), risk (90), and regulation (89).

The keywords also show that efficiency through data envelopment analysis is a determinant of the performance of banks. The other significant determinants that appeared as keywords are credit risk (73), competition (70), financial stability (69), ownership structure (57), capital (56), corporate social responsibility (56), liquidity (46), diversification (45), sustainability (44), credit provision (41), economic growth (41), capital structure (39), microfinance (39), Basel III (37), non-performing assets (37), cost efficiency (30), lending behavior (30), interest rate (29), mergers and acquisition (28), capital adequacy (26), developing countries (23), net interest margin (23), board of directors (21), disclosure (21), leverage (21), productivity (20), innovation (18), firm size (16), and firm value (16).

Keyword analysis also shows the theories of banking and their determinants. Some of the theories are agency theory (23), information asymmetry (21), moral hazard (17), and market efficiency (16), which can be used by researchers when building a theory. The analysis also helps to determine the methodology that was used in the published articles; some of them are data envelopment analysis (89), which measures technical efficiency, panel data analysis (61), DEA (32), Z scores (27), regression analysis (23), stochastic frontier analysis (20), event study (15), and literature review (15). The count for literature review is only 15, which confirms that very few studies have conducted an SLR on bank risk, regulation, and profitability.

Citation analysis

One of the parameters used in judging the quality of the article is its “citation.” Table 5 shows the top 10 published articles with the highest number of citations. Ding and Cronin [ 44 ] indicated that the popularity of an article depends on the number of times it has been cited.

Tahamtan et al. [ 126 ] explained that the journal’s quality also affects its published articles’ citations. A quality journal will have a high impact factor and, therefore, more citations. The citation analysis helps researchers to identify seminal articles. The title of an article with 5900 citations is “A survey of corporate governance.”

Page Rank analysis

Goyal and Kumar [ 53 ] explain that the citation analysis indicates the ‘popularity’ and ‘prestige’ of the published research article. Apart from the citation analysis, one more analysis is essential: Page rank analysis. PageRank is given by Page et al. [ 97 ]. The impact of an article can be measured with one indicator called PageRank [ 135 ]. Page rank analysis indicates how many times an article is cited by other highly cited articles. The method helps analyze the web pages, which get the priority during any search done on google. The analysis helps in understanding the citation networks. Equation 1 explains the page rank (PR) of a published paper, N refers to the number of articles.

T 1,… T n indicates the paper, which refers paper P . C ( Ti ) indicates the number of citations. The damping factor is denoted by a “ d ” which varies in the range of 0 and 1. The page rank of all the papers is equal to 1. Table 6 shows the top papers based on page rank. Tables 5 and 6 together show a contrast in the top ranked articles based on citations and page rank, respectively. Only one article “A survey of corporate governance” falls under the prestigious articles based on the page rank.

Content analysis

Content Analysis is a research technique for conducting qualitative and quantitative analyses [ 124 ]. The content analysis is a helpful technique that provides the required information in classifying the articles depending on their nature (empirical or conceptual) [ 76 ]. By adopting the content analysis method [ 53 , 102 ], the selected articles are examined to determine their content. The classification of available content from the selected set of sample articles that are categorized under different subheads. The themes identified in the relationship between banking regulation, risk, and profitability are as follows.

Regulation and profitability of banks

The performance indicators of the banking industry have always been a topic of interest to researchers and practitioners. This area of research has assumed a special interest after the 2008 WFC [ 25 , 51 , 86 , 114 , 127 , 132 ]. According to research, the causes of poor performance and risk management are lousy banking practices, ineffective monitoring, inadequate supervision, and weak regulatory mechanisms [ 94 ]. Increased competition, deregulation, and complex financial instruments have made banks, including Indian banks, more vulnerable to risks [ 18 , 93 , 119 , 123 ]. Hence, it is essential to investigate the present regulatory machinery for the performance of banks.

There are two schools of thought on regulation and its possible impact on profitability. The first asserts that regulation does not affect profitability. The second asserts that regulation adds significant value to banks’ profitability and other performance indicators. This supports the concept that Delis et al. [ 41 ] advocated that the capital adequacy requirement and supervisory power do not affect productivity or profitability unless there is a financial crisis. Laeven and Majnoni [ 81 ] insisted that provision for loan loss should be part of capital requirements. This will significantly improve active risk management practices and ensure banks’ profitability.

Lee and Hsieh [ 83 ] proposed ambiguous findings that do not support either school of thought. According to Nguyen and Nghiem [ 95 ], while regulation is beneficial, it has a negative impact on bank profitability. As a result, when proposing regulations, it is critical to consider bank performance and risk management. According to Erfani and Vasigh [ 46 ], Islamic banks maintained their efficiency between 2006 and 2013, while most commercial banks lost, furthermore claimed that the financial crisis had no significant impact on Islamic bank profitability.

Regulation and NPA (risk-taking of banks)

The regulatory mechanism of banks in any country must address the following issues: capital adequacy ratio, prudent provisioning, concentration banking, the ownership structure of banks, market discipline, regulatory devices, presence of foreign capital, bank competition, official supervisory power, independence of supervisory bodies, private monitoring, and NPAs [ 25 ].

Kanoujiya et al. [ 64 ] revealed through empirical evidence that Indian bank regulations lack a proper understanding of what banks require and propose reforming and transforming regulation in Indian banks so that responsive governance and regulation can occur to make banks safer, supported by Rastogi et al. [ 105 ]. The positive impact of regulation on NPAs is widely discussed in the literature. [ 94 ] argue that regulation has multiple effects on banks, including reducing NPAs. The influence is more powerful if the country’s banking system is fragile. Regulation, particularly capital regulation, is extremely effective in reducing risk-taking in banks [ 103 ].

Rastogi and Kanoujiya [ 106 ] discovered evidence that disclosure regulations do not affect the profitability of Indian banks, supported by Karyani et al. [ 65 ] for the banks located in Asia. Furthermore, Rastogi and Kanoujiya [ 106 ] explain that disclosure is a difficult task as a regulatory requirement. It is less sustainable due to the nature of the imposed regulations in banks and may thus be perceived as a burden and may be overcome by realizing the benefits associated with disclosure regulation [ 31 , 54 , 101 ]. Zheng et al. [ 138 ] empirically discovered that regulation has no impact on the banks’ profitability in Bangladesh.

Governments enforce banking regulations to achieve a stable and efficient financial system [ 20 , 94 ]. The existing literature is inconclusive on the effects of regulatory compliance on banks’ risks or the reduction of NPAs [ 10 , 11 ]. Boudriga et al. [ 25 ] concluded that the regulatory mechanism plays an insignificant role in reducing NPAs. This is especially true in weak institutions, which are susceptible to corruption. Gonzalez [ 52 ] reported that firm regulations have a positive relationship with banks’ risk-taking, increasing the probability of NPAs. However, Boudriga et al. [ 25 ], Samitas and Polyzos [ 113 ], and Allen et al. [ 3 ] strongly oppose the use of regulation as a tool to reduce banks’ risk-taking.

Kwan and Laderman [ 79 ] proposed three levels in regulating banks, which are lax, liberal, and strict. The liberal regulatory framework leads to more diversification in banks. By contrast, the strict regulatory framework forces the banks to take inappropriate risks to compensate for the loss of business; this is a global problem [ 73 ].

Capital regulation reduces banks’ risk-taking [ 103 , 110 ]. Capital regulation leads to cost escalation, but the benefits outweigh the cost [ 103 ]. The trade-off is worth striking. Altman Z score is used to predict banks’ bankruptcy, and it found that the regulation increased the Altman’s Z-score [ 4 , 46 , 63 , 68 , 72 , 120 ]. Jin et al. [ 62 ] report a negative relationship between regulation and banks’ risk-taking. Capital requirements empowered regulators, and competition significantly reduced banks’ risk-taking [ 1 , 122 ]. Capital regulation has a limited impact on banks’ risk-taking [ 90 , 103 ].

Maji and De [ 90 ] suggested that human capital is more effective in managing banks’ credit risks. Besanko and Kanatas [ 21 ] highlighted that regulation on capital requirements might not mitigate risks in all scenarios, especially when recapitalization has been enforced. Klomp and De Haan [ 72 ] proposed that capital requirements and supervision substantially reduce banks’ risks.

A third-party audit may impart more legitimacy to the banking system [ 23 ]. The absence of third-party intervention is conspicuous, and this may raise a doubt about the reliability and effectiveness of the impact of regulation on bank’s risk-taking.

NPA (risk-taking) in banks and profitability

Profitability affects NPAs, and NPAs, in turn, affect profitability. According to the bad management hypothesis [ 17 ], higher profits would negatively affect NPAs. By contrast, higher profits may lead management to resort to a liberal credit policy (high earnings), which may eventually lead to higher NPAs [ 104 ].

Balasubramaniam [ 8 ] demonstrated that NPA has double negative effects on banks. NPAs increase stressed assets, reducing banks’ productive assets [ 92 , 117 , 136 ]. This phenomenon is relatively underexplored and therefore renders itself for future research.

Triad and the performance of banks

Regulation and triad.

Regulations and their impact on banks have been a matter of debate for a long time. Barth et al. [ 12 ] demonstrated that countries with a central bank as the sole regulatory body are prone to high NPAs. Although countries with multiple regulatory bodies have high liquidity risks, they have low capital requirements [ 40 ]. Barth et al. [ 12 ] supported the following steps to rationalize the existing regulatory mechanism on banks: (1) mandatory information [ 22 ], (2) empowered management of banks, and (3) increased incentive for private agents to exert corporate control. They show that profitability has an inverse relationship with banks’ risk-taking [ 114 ]. Therefore, standard regulatory practices, such as capital requirements, are not beneficial. However, small domestic banks benefit from capital restrictions.

DeYoung and Jang [ 43 ] showed that Basel III-based policies of liquidity convergence ratio (LCR) and net stable funding ratio (NSFR) are not fully executed across the globe, including the US. Dahir et al. [ 39 ] found that a decrease in liquidity and funding increases banks’ risk-taking, making banks vulnerable and reducing stability. Therefore, any regulation on liquidity risk is more likely to create problems for banks.

Concentration banking and triad

Kiran and Jones [ 71 ] asserted that large banks are marginally affected by NPAs, whereas small banks are significantly affected by high NPAs. They added a new dimension to NPAs and their impact on profitability: concentration banking or banks’ market power. Market power leads to less cost and more profitability, which can easily counter the adverse impact of NPAs on profitability [ 6 , 15 ].

The connection between the huge volume of research on the performance of banks and competition is the underlying concept of market power. Competition reduces market power, whereas concentration banking increases market power [ 25 ]. Concentration banking reduces competition, increases market power, rationalizes the banks’ risk-taking, and ensures profitability.

Tabak et al. [ 125 ] advocated that market power incentivizes banks to become risk-averse, leading to lower costs and high profits. They explained that an increase in market power reduces the risk-taking requirement of banks. Reducing banks’ risks due to market power significantly increases when capital regulation is executed objectively. Ariss [ 6 ] suggested that increased market power decreases competition, and thus, NPAs reduce, leading to increased banks’ stability.

Competition, the performance of banks, and triad

Boyd and De Nicolo [ 27 ] supported that competition and concentration banking are inversely related, whereas competition increases risk, and concentration banking decreases risk. A mere shift toward concentration banking can lead to risk rationalization. This finding has significant policy implications. Risk reduction can also be achieved through stringent regulations. Bolt and Tieman [ 24 ] explained that stringent regulation coupled with intense competition does more harm than good, especially concerning banks’ risk-taking.

Market deregulation, as well as intensifying competition, would reduce the market power of large banks. Thus, the entire banking system might take inappropriate and irrational risks [ 112 ]. Maji and Hazarika [ 91 ] added more confusion to the existing policy by proposing that, often, there is no relationship between capital regulation and banks’ risk-taking. However, some cases have reported a positive relationship. This implies that banks’ risk-taking is neutral to regulation or leads to increased risk. Furthermore, Maji and Hazarika [ 91 ] revealed that competition reduces banks’ risk-taking, contrary to popular belief.

Claessens and Laeven [ 36 ] posited that concentration banking influences competition. However, this competition exists only within the restricted circle of banks, which are part of concentration banking. Kasman and Kasman [ 66 ] found that low concentration banking increases banks’ stability. However, they were silent on the impact of low concentration banking on banks’ risk-taking. Baselga-Pascual et al. [ 14 ] endorsed the earlier findings that concentration banking reduces banks’ risk-taking.

Concentration banking and competition are inversely related because of the inherent design of concentration banking. Market power increases when only a few large banks are operating; thus, reduced competition is an obvious outcome. Barra and Zotti [ 9 ] supported the idea that market power, coupled with competition between the given players, injects financial stability into banks. Market power and concentration banking affect each other. Therefore, concentration banking with a moderate level of regulation, instead of indiscriminate regulation, would serve the purpose better. Baselga-Pascual et al. [ 14 ] also showed that concentration banking addresses banks’ risk-taking.

Schaeck et al. [ 115 ], in a landmark study, presented that concentration banking and competition reduce banks’ risk-taking. However, they did not address the relationship between concentration banking and competition, which are usually inversely related. This could be a subject for future research. Research on the relationship between concentration banking and competition is scant, identified as a research gap (“ Research Implications of the study ” section).

Transparency, corporate governance, and triad

One of the big problems with NPAs is the lack of transparency in both the regulatory bodies and banks [ 25 ]. Boudriga et al. [ 25 ] preferred to view NPAs as a governance issue and thus, recommended viewing it from a governance perspective. Ahmad and Ariff [ 2 ] concluded that regulatory capital and top-management quality determine banks’ credit risk. Furthermore, they asserted that credit risk in emerging economies is higher than that of developed economies.

Bad management practices and moral vulnerabilities are the key determinants of insolvency risks of Indian banks [ 95 ]. Banks are an integral part of the economy and engines of social growth. Therefore, banks enjoy liberal insolvency protection in India, especially public sector banks, which is a critical issue. Such a benevolent insolvency cover encourages a bank to be indifferent to its capital requirements. This indifference takes its toll on insolvency risk and profit efficiency. Insolvency protection makes the bank operationally inefficient and complacent.

Foreign equity and corporate governance practices help manage the adverse impact of banks’ risk-taking to ensure the profitability and stability of banks [ 33 , 34 ]. Eastburn and Sharland [ 45 ] advocated that sound management and a risk management system that can anticipate any impending risk are essential. A pragmatic risk mechanism should replace the existing conceptual risk management system.

Lo [ 87 ] found and advocated that the existing legislation and regulations are outdated. He insisted on a new perspective and asserted that giving equal importance to behavioral aspects and the rational expectations of customers of banks is vital. Buston [ 29 ] critiqued the balance sheet risk management practices prevailing globally. He proposed active risk management practices that provided risk protection measures to contain banks’ liquidity and solvency risks.

Klomp and De Haan [ 72 ] championed the cause of giving more autonomy to central banks of countries to provide stability in the banking system. Louzis et al. [ 88 ] showed that macroeconomic variables and the quality of bank management determine banks’ level of NPAs. Regulatory authorities are striving hard to make regulatory frameworks more structured and stringent. However, the recent increase in loan defaults (NPAs), scams, frauds, and cyber-attacks raise concerns about the effectiveness [ 19 ] of the existing banking regulations in India as well as globally.

Discussion of the findings

The findings of this study are based on the bibliometric and content analysis of the sample published articles.

The bibliometric study concludes that there is a growing demand for researchers and good quality research

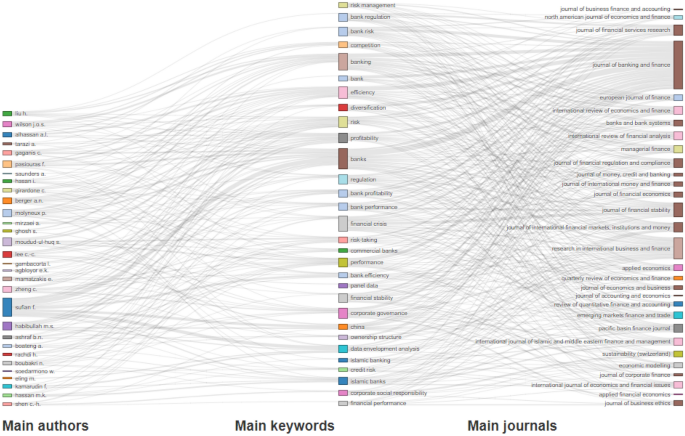

The keyword analysis suggests that risk regulation, competition, profitability, and performance are key elements in understanding the banking system. The main authors, keywords, and journals are grouped in a Sankey diagram in Fig. 6 . Researchers can use the following information to understand the publication pattern on banking and its determinants.

Sankey Diagram of main authors, keywords, and journals. Note Authors contribution using scientometrics tools

Research Implications of the study

The study also concludes that a balance among the three components of triad is the solution to the challenges of banks worldwide, including India. We propose the following recommendations and implications for banks:

This study found that “the lesser the better,” that is, less regulation enhances the performance and risk management of banks. However, less regulation does not imply the absence of regulation. Less regulation means the following:

Flexible but full enforcement of the regulations

Customization, instead of a one-size-fits-all regulatory system rooted in a nation’s indigenous requirements, is needed. Basel or generic regulation can never achieve what a customized compliance system can.

A third-party audit, which is above the country's central bank, should be mandatory, and this would ensure that all three aspects of audit (policy formulation, execution, and audit) are handled by different entities.

Competition

This study asserts that the existing literature is replete with poor performance and risk management due to excessive competition. Banking is an industry of a different genre, and it would be unfair to compare it with the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) or telecommunication industry, where competition injects efficiency into the system, leading to customer empowerment and satisfaction. By contrast, competition is a deterrent to the basic tenets of safe banking. Concentration banking is more effective in handling the multi-pronged balance between the elements of the triad. Concentration banking reduces competition to lower and manageable levels, reduces banks’ risk-taking, and enhances profitability.

No incentive to take risks

It is found that unless banks’ risk-taking is discouraged, the problem of high NPA (risk-taking) cannot be addressed. Concentration banking is a disincentive to risk-taking and can be a game-changer in handling banks’ performance and risk management.

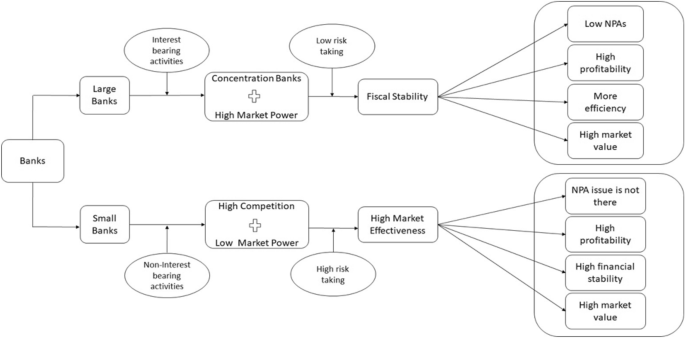

Research on the risk and performance of banks reveals that the existing regulatory and policy arrangement is not a sustainable proposition, especially for a country where half of the people are unbanked [ 37 ]. Further, the triad presented by Keeley [ 67 ] is a formidable real challenge to bankers. The balance among profitability, risk-taking, and regulation is very subtle and becomes harder to strike, just as the banks globally have tried hard to achieve it. A pragmatic intervention is needed; hence, this study proposes a change in the banking structure by having two types of banks functioning simultaneously to solve the problems of risk and performance of banks. The proposed two-tier banking system explained in Fig. 7 can be a great solution. This arrangement will help achieve the much-needed balance among the elements of triad as presented by Keeley [ 67 ].

Conceptual Framework. Note Fig. 7 describes the conceptual framework of the study

The first set of banks could be conventional in terms of their structure and should primarily be large-sized. The number of such banks should be moderate. There is a logic in having only a few such banks to restrict competition; thus, reasonable market power could be assigned to them [ 55 ]. However, a reduction in competition cannot be over-assumed, and banks cannot become complacent. As customary, lending would be the main source of revenue and income for these banks (fund based activities) [ 82 ]. The proposed two-tier system can be successful only when regulation especially for risk is objectively executed [ 29 ]. The second set of banks could be smaller in size and more in number. Since they are more in number, they would encounter intense competition for survival and for generating more business. Small is beautiful, and thus, this set of banks would be more agile and adaptable and consequently more efficient and profitable. The main source of revenue for this set of banks would not be loans and advances. However, non-funding and non-interest-bearing activities would be the major revenue source. Unlike their traditional and large-sized counterparts, since these banks are smaller in size, they are less likely to face risk-taking and NPAs [ 74 ].

Sarmiento and Galán [ 114 ] presented the concerns of large and small banks and their relative ability and appetite for risk-taking. High risk could threaten the existence of small-sized banks; thus, they need robust risk shielding. Small size makes them prone to failure, and they cannot convert their risk into profitability. However, large banks benefit from their size and are thus less vulnerable and can convert risk into profitable opportunities.

India has experimented with this Differential Banking System (DBS) (two-tier system) only at the policy planning level. The execution is impending, and it highly depends on the political will, which does not appear to be strong now. The current agenda behind the DBS model is not to ensure the long-term sustainability of banks. However, it is currently being directed to support the agenda of financial inclusion by extending the formal credit system to the unbanked masses [ 107 ]. A shift in goal is needed to employ the DBS as a strategic decision, but not merely a tool for financial inclusion. Thus, the proposed two-tier banking system (DBS) can solve the issue of profitability through proper regulation and less risk-taking.

The findings of Triki et al. [ 130 ] support the proposed DBS model, in this study. Triki et al. [ 130 ] advocated that different component of regulations affect banks based on their size, risk-taking, and concentration banking (or market power). Large size, more concentration banking with high market power, and high risk-taking coupled with stringent regulation make the most efficient banks in African countries. Sharifi et al. [ 119 ] confirmed that size advantage offers better risk management to large banks than small banks. The banks should modify and work according to the economic environment in the country [ 69 ], and therefore, the proposed model could help in solving the current economic problems.

This is a fact that DBS is running across the world, including in India [ 60 ] and other countries [ 133 ]. India experimented with DBS in the form of not only regional rural banks (RRBs) but payments banks [ 109 ] and small finance banks as well [ 61 ]. However, the purpose of all the existing DBS models, whether RRBs [ 60 ], payment banks, or small finance banks, is financial inclusion, not bank performance and risk management. Hence, they are unable to sustain and are failing because their model is only social instead of a much-needed dual business-cum-social model. The two-tier model of DBS proposed in the current paper can help serve the dual purpose. It may not only be able to ensure bank performance and risk management but also serve the purpose of inclusive growth of the economy.

Conclusion of the study

The study’s conclusions have some significant ramifications. This study can assist researchers in determining their study plan on the current topic by using a scientific approach. Citation analysis has aided in the objective identification of essential papers and scholars. More collaboration between authors from various countries/universities may help countries/universities better understand risk regulation, competition, profitability, and performance, which are critical elements in understanding the banking system. The regulatory mechanism in place prior to 2008 failed to address the risk associated with banks [ 47 , 87 ]. There arises a necessity and motivates authors to investigate the current topic. The present study systematically explores the existing literature on banks’ triad: performance, regulation, and risk management and proposes a probable solution.

To conclude the bibliometric results obtained from the current study, from the number of articles published from 1976 to 2020, it is evident that most of the articles were published from the year 2010, and the highest number of articles were published in the last five years, i.e., is from 2015. The authors discovered that researchers evaluate articles based on the scope of critical journals within the subject area based on the detailed review. Most risk, regulation, and profitability articles are published in peer-reviewed journals like; “Journal of Banking and Finance,” “Journal of Accounting and Economics,” and “Journal of Financial Economics.” The rest of the journals are presented in Table 1 . From the affiliation statistics, it is clear that most of the research conducted was affiliated with developed countries such as Malaysia, the USA, and the UK. The researchers perform content analysis and Citation analysis to access the type of content where the research on the current field of knowledge is focused, and citation analysis helps the academicians understand the highest cited articles that have more impact in the current research area.

Practical implications of the study

The current study is unique in that it is the first to systematically evaluate the publication pattern in banking using a combination of scientometrics analysis tools, network analysis tools, and content analysis to understand the relationship between bank regulation, performance, and risk. The study’s practical implications are that analyzing existing literature helps researchers generate new themes and ideas to justify their contribution to literature. Evidence-based research knowledge also improves decision-making, resulting in better practical implementation in the real corporate world [ 100 , 129 ].

Limitations and scope for future research

The current study only considers a single database Scopus to conduct the study, and this is one of the limitations of the study spanning around the multiple databases can provide diverse results. The proposed DBS model is a conceptual framework that requires empirical testing, which is a limitation of this study. As a result, empirical testing of the proposed DBS model could be a future research topic.

Availability of data and materials

SCOPUS database.

Abbreviations

Systematic literature review

World Financial Crisis

Non-performing assets

Differential banking system

SCImago Journal Rank Indicator

Liquidity convergence ratio

Net stable funding ratio

Fast moving consumer goods

Regional rural banks

Agoraki M-EK, Delis MD, Pasiouras F (2011) Regulations, competition and bank risk-taking in transition countries. J Financ Stab 7(1):38–48

Google Scholar

Ahmad NH, Ariff M (2007) Multi-country study of bank credit risk determinants. Int J Bank Financ 5(1):35–62

Allen B, Chan KK, Milne A, Thomas S (2012) Basel III: Is the cure worse than the disease? Int Rev Financ Anal 25:159–166

Altman EI (2018) A fifty-year retrospective on credit risk models, the Altman Z-score family of models, and their applications to financial markets and managerial strategies. J Credit Risk 14(4):1–34

Alvarez F, Jermann UJ (2000) Efficiency, equilibrium, and asset pricing with risk of default. Econometrica 68(4):775–797

Ariss RT (2010) On the implications of market power in banking: evidence from developing countries. J Bank Financ 34(4):765–775

Aznar-Sánchez JA, Piquer-Rodríguez M, Velasco-Muñoz JF, Manzano-Agugliaro F (2019) Worldwide research trends on sustainable land use in agriculture. Land Use Policy 87:104069

Balasubramaniam C (2012) Non-performing assets and profitability of commercial banks in India: assessment and emerging issues. Nat Mon Refereed J Res Commer Manag 1(1):41–52

Barra C, Zotti R (2017) On the relationship between bank market concentration and stability of financial institutions: evidence from the Italian banking sector, MPRA working Paper No 79900. Last Accessed on Jan 2021 https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/79900/1/MPRA_paper_79900.pdf

Barth JR, Caprio G, Levine R (2004) Bank regulation and supervision: what works best? J Financ Intermed 2(13):205–248

Barth JR, Caprio G, Levine R (2008) Bank regulations are changing: For better or worse? Comp Econ Stud 50(4):537–563

Barth JR, Dopico LG, Nolle DE, Wilcox JA (2002) Bank safety and soundness and the structure of bank supervision: a cross-country analysis. Int Rev Financ 3(3–4):163–188

Bartolini M, Bottani E, Grosse EH (2019) Green warehousing: systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. J Clean Prod 226:242–258

Baselga-Pascual L, Trujillo-Ponce A, Cardone-Riportella C (2015) Factors influencing bank risk in Europe: evidence from the financial crisis. N Am J Econ Financ 34(1):138–166

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2006) Bank concentration, competition, and crises: first results. J Bank Financ 30(5):1581–1603

Berger AN, Demsetz RS, Strahan PE (1999) The consolidation of the financial services industry: causes, consequences, and implications for the future. J Bank Financ 23(2–4):135–194

Berger AN, Deyoung R (1997) Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. J Bank Financ 21(6):849–870

Berger AN, Udell GF (1998) The economics of small business finance: the roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. J Bank Financ 22(6–8):613–673

Berger AN, Udell GF (2002) Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organisational structure. Econ J 112(477):F32–F53

Berger AN, Udell GF (2006) A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. J Bank Financ 30(11):2945–2966

Besanko D, Kanatas G (1996) The regulation of bank capital: Do capital standards promote bank safety? J Financ Intermed 5(2):160–183

Beyer A, Cohen DA, Lys TZ, Walther BR (2010) The financial reporting environment: review of the recent literature. J Acc Econ 50(2–3):296–343

Bikker JA (2010) Measuring performance of banks: an assessment. J Appl Bus Econ 11(4):141–159

Bolt W, Tieman AF (2004) Banking competition, risk and regulation. Scand J Econ 106(4):783–804

Boudriga A, BoulilaTaktak N, Jellouli S (2009) Banking supervision and non-performing loans: a cross-country analysis. J Financ Econ Policy 1(4):286–318

Bouzon M, Miguel PAC, Rodriguez CMT (2014) Managing end of life products: a review of the literature on reverse logistics in Brazil. Manag Environ Qual Int J 25(5):564–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-04-2013-0027

Article Google Scholar

Boyd JH, De Nicolo G (2005) The theory of bank risk taking and competition revisited. J Financ 60(3):1329–1343

Brealey RA, Myers SC, Allen F, Mohanty P (2012) Principles of corporate finance. Tata McGraw-Hill Education

Buston CS (2016) Active risk management and banking stability. J Bank Financ 72:S203–S215

Casu B, Girardone C (2006) Bank competition, concentration and efficiency in the single European market. Manch Sch 74(4):441–468

Charumathi B, Ramesh L (2020) Impact of voluntary disclosure on valuation of firms: evidence from Indian companies. Vision 24(2):194–203

Chen X (2007) Banking deregulation and credit risk: evidence from the EU. J Financ Stab 2(4):356–390

Chen H-J, Lin K-T (2016) How do banks make the trade-offs among risks? The role of corporate governance. J Bank Financ 72(1):S39–S69

Chen M, Wu J, Jeon BN, Wang R (2017) Do foreign banks take more risk? Evidence from emerging economies. J Bank Financ 82(1):20–39

Claessens S, Laeven L (2003) Financial development, property rights, and growth. J Financ 58(6):2401–2436. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6261.2003.00610.x

Claessens S, Laeven L (2004) What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. J Money Credit Bank 36(3):563–583

Cnaan RA, Moodithaya M, Handy F (2012) Financial inclusion: lessons from rural South India. J Soc Policy 41(1):183–205

Core JE, Holthausen RW, Larcker DF (1999) Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. J Financ Econ 51(3):371–406

Dahir AM, Mahat FB, Ali NAB (2018) Funding liquidity risk and bank risk-taking in BRICS countries: an application of system GMM approach. Int J Emerg Mark 13(1):231–248

Dechow P, Ge W, Schrand C (2010) Understanding earnings quality: a review of the proxies, their determinants, and their consequences. J Acc Econ 50(2–3):344–401

Delis MD, Molyneux P, Pasiouras F (2011) Regulations and productivity growth in banking: evidence from transition economies. J Money Credit Bank 43(4):735–764

Demirguc-Kunt A, Laeven L, Levine R (2003) Regulations, market structure, institutions, and the cost of financial intermediation (No. w9890). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Deyoung R, Jang KY (2016) Do banks actively manage their liquidity? J Bank Financ 66:143–161

Ding Y, Cronin B (2011) Popularand/orprestigious? Measures of scholarly esteem. Inf Process Manag 47(1):80–96

Eastburn RW, Sharland A (2017) Risk management and managerial mindset. J Risk Financ 18(1):21–47

Erfani GR, Vasigh B (2018) The impact of the global financial crisis on profitability of the banking industry: a comparative analysis. Economies 6(4):66

Erkens DH, Hung M, Matos P (2012) Corporate governance in the 2007–2008 financial crisis: evidence from financial institutions worldwide. J Corp Finan 18(2):389–411

Fahimnia B, Sarkis J, Davarzani H (2015) Green supply chain management: a review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Prod Econ 162:101–114

Financial Stability Report (2019) Financial stability report (20), December 2019. https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=946 Accesses on March 2020

Fink A (2005) Conducting Research Literature Reviews:From the Internet to Paper, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications

Ghosh A (2015) Banking-industry specific and regional economic determinants of non-performing loans: evidence from US states. J Financ Stab 20:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2015.08.004

Gonzalez F (2005) Bank regulation and risk-taking incentives: an international comparison of bank risk. J Bank Financ 29(5):1153–1184

Goyal K, Kumar S (2021) Financial literacy: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Consum Stud 45(1):80–105

Grassa R, Moumen N, Hussainey K (2020) Do ownership structures affect risk disclosure in Islamic banks? International evidence. J Financ Rep Acc 19(3):369–391

Haque F, Shahid R (2016) Ownership, risk-taking and performance of banks in emerging economies: evidence from India. J Financ Econ Policy 8(3):282–297

Hellmann TF, Murdock KC, Stiglitz JE (2000) Liberalization, moral hazard in banking, and prudential regulation: Are capital requirements enough? Am Econ Rev 90(1):147–165

Hirshleifer D (2001) Investor psychology and asset pricing. J Financ 56(4):1533–1597

Huang J, You JX, Liu HC, Song MS (2020) Failure mode and effect analysis improvement: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 199:106885

Ibáñez Zapata A (2017) Bibliometric analysis of the regulatory compliance function within the banking sector (Doctoral dissertation). Last Accessed on Jan 2021 https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/85952/Bibliometric%20analysis_AIZ_v4.pdf?sequence=1

Ibrahim MS (2010) Performance evaluation of regional rural banks in India. Int Bus Res 3(4):203–211

Jayadev M, Singh H, Kumar P (2017) Small finance banks: challenges. IIMB Manag Rev 29(4):311–325

Jin JY, Kanagaretnam K, Lobo GJ, Mathieu R (2013) Impact of FDICIA internal controls on bank risk taking. J Bank Financ 37(2):614–624

Joshi MK (2020) Financial performance analysis of select Indian Public Sector Banks using Altman’s Z-Score model. SMART J Bus Manag Stud 16(2):74–87

Kanoujiya J, Bhimavarapu VM, Rastogi S (2021) Banks in India: a balancing act between profitability, regulation and NPA. Vision, 09722629211034417

Karyani E, Dewo SA, Santoso W, Frensidy B (2020) Risk governance and bank profitability in ASEAN-5: a comparative and empirical study. Int J Emerg Mark 15(5):949–969

Kasman S, Kasman A (2015) Bank competition, concentration and financial stability in the Turkish banking industry. Econ Syst 39(3):502–517

Keeley MC (1990) Deposit insurance, risk, and market power in banking. Am Econ Rev 1:1183–1200

Khaddafi M, Heikal M, Nandari A (2017) Analysis Z-score to predict bankruptcy in banks listed in indonesia stock exchange. Int J Econ Financ Issues 7(3):326–330

Khanna T, Yafeh Y (2007) Business groups in emerging markets: Paragons or parasites? J Econ Lit 45(2):331–372

King RG, Levine R (1993) Finance and growth: schumpeter might be right. Q J Econ 108(3):717–737

Kiran KP, Jones TM (2016) Effect of non performing assets on the profitability of banks–a selective study. Int J Bus Gen Manag 5(2):53–60

Klomp J, De Haan J (2015) Banking risk and regulation: Does one size fit all? J Bank Financ 36(12):3197–3212

Koehn M, Santomero AM (1980) Regulation of bank capital and portfolio risk. J Financ 35(5):1235–1244

Köhler M (2015) Which banks are more risky? The impact of business models on bank stability. J Financ Stab 16(1):195–212

Kothari SP (2001) Capital markets research in accounting. J Account Econ 31(1–3):105–231

Kumar S, Goyal N (2015) Behavioural biases in investment decision making – a systematic literature review. Qual Res Financ Mark 7(1):88–108

Kumar S, Kamble S, Roy MH (2020) Twenty-five years of Benchmarking: an International Journal (BIJ): a bibliometric overview. Benchmarking Int J 27(2):760–780. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2019-0314

Kumar S, Sureka R, Colombage S (2020) Capital structure of SMEs: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Manag Rev Q 70(4):535–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00175-4

Kwan SH, Laderman ES (1999) On the portfolio effects of financial convergence-a review of the literature. Econ Rev 2:18–31

Lado AA, Boyd NG, Hanlon SC (1997) Competition, cooperation, and the search for economic rents: a syncretic model. Acad Manag Rev 22(1):110–141

Laeven L, Majnoni G (2003) Loan loss provisioning and economic slowdowns: Too much, too late? J Financ Intermed 12(2):178–197

Laeven L, Ratnovski L, Tong H (2016) Bank size, capital, and systemic risk: Some international evidence. J Bank Finance 69(1):S25–S34

Lee C-C, Hsieh M-F (2013) The impact of bank capital on profitability and risk in Asian banking. J Int Money Financ 32(1):251–281

Leech D, Leahy J (1991) Ownership structure, control type classifications and the performance of large British companies. Econ J 101(409):1418–1437

Levine R (1997) Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda. J Econ Lit 35(2):688–726

Lim CY, Woods M, Humphrey C, Seow JL (2017) The paradoxes of risk management in the banking sector. Br Acc Rev 49(1):75–90

Lo AW (2009) Regulatory reform in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. J Financ Econ Policy 1(1):4–43

Louzis DP, Vouldis AT, Metaxas VL (2012) Macroeconomic and bank-specific determinants of non-performing loans in Greece: a comparative study of mortgage, business and consumer loan portfolios. J Bank Financ 36(4):1012–1027

Maddaloni A, Peydró J-L (2011) Bank risk-taking, securitization, supervision, and low interest rates: evidence from the Euro-area and the U.S. lending standards. Rev Financ Stud 24(6):2121–2165. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhr015

Maji SG, De UK (2015) Regulatory capital and risk of Indian banks: a simultaneous equation approach. J Financ Econ Policy 7(2):140–156

Maji SG, Hazarika P (2018) Capital regulation, competition and risk-taking behavior of Indian banks in a simultaneous approach. Manag Financ 44(4):459–477

Messai AS, Jouini F (2013) Micro and macro determinants of non-performing loans. Int J Econ Financ Issues 3(4):852–860

Mitra S, Karathanasopoulos A, Sermpinis G, Dunis C, Hood J (2015) Operational risk: emerging markets, sectors and measurement. Eur J Oper Res 241(1):122–132

Mohsni S, Otchere I (2018) Does regulatory regime matter for bank risk-taking? A comparative analysis of US and Canada, d/Seas Working Papers-ISSN 2611-0172 1(1):28–28

Nguyen TPT, Nghiem SH (2015) The interrelationships among default risk, capital ratio and efficiency: evidence from Indian banks. Manag Financ 41(5):507–525

Niinimäki J-P (2004) The effects of competition on banks’ risk taking. J Econ 81(3):199–222

Page L, Brin S, Motwani R, Winograd T (1999) The PageRank citation ranking: bringing order to the web. Stanford InfoLab

Pakravan K (2014) Bank capital: the case against Basel. J Financ Regul Compl 22(3):208–218

Palacios-Callender M, Roberts SA, Roth-Berghofer T (2016) Evaluating patterns of national and international collaboration in Cuban science using bibliometric tools. J Doc 72(2):362–390. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-11-2014-0164

Pinto G, Rastogi S, Kadam S, Sharma A (2019) Bibliometric study on dividend policy. Qual Res Financ Mark 12(1):72–95

Polizzi S, Scannella E (2020) An empirical investigation into market risk disclosure: Is there room to improve for Italian banks? J Financ Regul Compl 28(3):465–483

Prasad P, Narayanasamy S, Paul S, Chattopadhyay S, Saravanan P (2019) Review of literature on working capital management and future research agenda. J Econ Surv 33(3):827–861

Rahman MM, Zheng C, Ashraf BN, Rahman MM (2018) Capital requirements, the cost of financial intermediation and bank risk-taking: empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Res Int Bus Financ 44(1):488–503

Rajan RG (1994) Why bank credit policies fluctuate: a theory and some evidence. Q J Econ 109(2):399–441

Rastogi S, Gupte R, Meenakshi R (2021) A holistic perspective on bank performance using regulation, profitability, and risk-taking with a view on ownership concentration. J Risk Financ Manag 14(3):111

Rastogi S, Kanoujiya J (2022) Does transparency and disclosure (T&D) improve the performance of banks in India? Int J Product Perform Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-10-2021-0613

Rastogi S, Ragabiruntha E (2018) Financial inclusion and socioeconomic development: gaps and solution. Int J Soc Econ 45(7):1122–1140

RBI (2001) Prudential Norms on income recognition, asset classification, and provisioning -pertaining to advances. Accessed on Apr 2020. https://rbidocs.rbi.org.in/rdocs/notification/PDFs/23068.pdf

Reddy S (2018) Announcement of payment banks and stock performance of commercial banks in India. J Internet Bank Commer 23(1):1–12

Repullo R (2004) Capital requirements, market power, and risk-taking in banking. J Financ Intermed 13(2):156–182

Rowley J, Slack F (2004) Conducting a literature review. Manag Res News 27(6):31–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170410784185

Salas V, Saurina J (2003) Deregulation, market power and risk behaviour in Spanish banks. Eur Econ Rev 47(6):1061–1075

Samitas A, Polyzos S (2015) To Basel or not to Basel? Banking crises and contagion. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 23(3):298–318

Sarmiento M, Galán JE (2017) The influence of risk-taking on bank efficiency: evidence from Colombia. Emerg Mark Rev 32:52–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2017.05.007

Schaeck K, Cihak M, Wolfe S (2009) Are competitive banking systems more stable? J Money Credit Bank 41(4):711–734

Schwerter S (2011) Basel III’s ability to mitigate systemic risk. J Financ Regul Compl 19(4):337–354

Sen S, Sen RL (2014) Impact of NPAs on bank profitability: an empirical study. In: Ray N, Chakraborty K (eds) Handbook of research on strategic business infrastructure development and contemporary issues in finance. IGI Global, pp 124–134. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-5154-8.ch010

Chapter Google Scholar

Shajahan K (1998) Non-performing assets of banks: Have they really declined? And on whose account? Econ Pol Wkly 33(12):671–674

Sharifi S, Haldar A, Rao SN (2016) Relationship between operational risk management, size, and ownership of Indian banks. Manag Financ 42(10):930–942

Sharma A, Theresa L, Mhatre J, Sajid M (2019) Application of altman Z-Score to RBI defaulters: Indian case. Asian J Res Bus Econ Manag 9(4):1–11

Shehzad CT, De Haan J (2015) Supervisory powers and bank risk taking. J Int Finan Markets Inst Money 39(1):15–24

Shen L, Xiong B, Hu J (2017) Research status, hotspotsandtrends forinformation behavior in China using bibliometric and co-word analysis. J Doc 73(4):618–633

Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1997) A survey of corporate governance. J Financ 52(2):737–783

Singh HP, Kumar S (2014) Working capital management: a literature review and research agenda. Qual Res Financ Mark 6(2):173–197

Tabak BM, Fazio DM, Cajueiro DO (2013) Systemically important banks and financial stability: the case of Latin America. J Bank Financ 37(10):3855–3866

Tahamtan I, SafipourAfshar A, Ahamdzadeh K (2016) Factors affecting number of citations: a comprehensive review of the literature. Scientometrics 107(3):1195–1225

Thakor AV (2018) Post-crisis regulatory reform in banking: Address insolvency risk, not illiquidity! J Financ Stab 37(1):107–111

Thomsen S, Pedersen T (2000) Ownership structure and economic performance in the largest European companies. Strategic Manag J 21(6):689–705

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14(3):207–222

Triki T, Kouki I, Dhaou MB, Calice P (2017) Bank regulation and efficiency: What works for Africa? Res Int Bus Financ 39(1):183–205

Tsay M, Shu Z (2011) Journal bibliometric analysis: a case study on the journal of documentation. J Doc 67(5):806–822

Vento GA, La Ganga P (2009) Bank liquidity risk management and supervision: which lessons from recent market turmoil. J Money Invest Bank 10(10):78–125

Wahid ANM (1994) The grameen bank and poverty alleviation in Bangladesh: theory, evidence and limitations. Am J Econ Sociol 53(1):1–15

Xiao Y, Watson M (2019) Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J Plan Educ Res 39(1):93–112

Xu X, Chen X, Jia F, Brown S, Gong Y, Xu Y (2018) Supply chain finance: a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Prod Econ 204:160–173

Yadav M (2011) Impact of non performing assets on profitability and productivity of public sector banks in India. AFBE J 4(1):232–239

Yong-Hak J (2013), Web of Science, Thomson Reuters

Zheng C, Rahman MM, Begum M, Ashraf BN (2017) Capital regulation, the cost of financial intermediation and bank profitability: evidence from Bangladesh. J Risk Financ Manag 10(2):9

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Symbiosis Institute of Business Management, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India

Shailesh Rastogi, Arpita Sharma & Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu

SIES School of Business Studies, Navi Mumbai, India

Geetanjali Pinto

School of Commerce and Management, D Y Patil International University, Akurdi, Pune, India

Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

‘SR’ performed Abstract, Introduction, and Data methodology sections and was the major contributor; ‘AS’ performed Bibliometric and Network analysis and conceptual framework; ‘GP’ performed citation analysis and discussion section; ‘VMB’ collated data from the database and concluded the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rastogi, S., Sharma, A., Pinto, G. et al. A literature review of risk, regulation, and profitability of banks using a scientometric study. Futur Bus J 8 , 28 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-022-00146-4

Download citation

Received : 11 March 2022

Accepted : 16 August 2022

Published : 03 September 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-022-00146-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bank performance

- Profitability

- Bibliometric analysis

- Scientometric analysis

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This study presents a systematic literature review of regulation, profitability, and risk in the banking industry and explores the relationship between them. It proposes a policy initiative using a model that offers guidelines to establish the right mix among these variables. This is a systematic literature review study. Firstly, the necessary data are extracted using the relevant keywords ...

Abstract: This study analyses existing literature review studies on banking sector. performance. Spec ially, this research aim is to identify topics of interest and development. niche for this ...

position and performance of public sector bank (SBI) and private sector bank (HDFC) in India. The article has been divided into eight sections. Section II covers literature review. Research gap has been mentioned in section III. Section IV and V contain objective and materials & methods of the study.

[Show full abstract] State Bank of India (SBI) and its associates, nationalised banks and private sector banks on the banking industry in this regard. Design/methodology/approach The individual ...

International Journal of New Innovations in Engineering and Technology, 19(1), 23-27, ISSN ISSN: 2319-6319 Google Scholar [49] Shukla, S. 2014. Employee Retention Policies of Public and Private Sector Banks in India: A Comparative Study. Integral Review: A Journal of Management, Dec2014, Vol. 7 Issue 2, p87-100. 14p.

This paper estimates and compares various efficiencies, namely, business, profit, and Z-Score efficiencies for private and publicly owned Indian banks. It uses the data envelopment analysis (DEA) following variable returns to scale, under input and output orientation, for measuring efficiency. Further, the Tobit regression model is used in the ...

This study is based on the analysis of private sector banks. Currently 22 banks are working under private sector banks in India. Out of 22 banks, following four banks are selected on the basis of market position, profitability and capitalization. 1. HDFC Bank (Housing Development Finance Corporation Limited)- 1994.

Literature Review (Parveen ... The objective of the study is to profitability and to evaluate the productivity of public and private sector bank with special reference to selected banks during the ...

2. To learn about the NPA positions of private and public sector banks over the previous decade. 3. To compare the level of non-performing assets (NPAs) in a sample of Indian private and public sector banks. 4. To provide a few ideas for improving the banks' NPA levels. Review Of Literature

2. Literature Review Several research studies are available, exploring different aspects of banking sector in India. However, there is still lack of up-to-date examination of financial performance of banks. This literature review charts out the most significant studies related to the topic of the present research article.