Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Steps in the literature review process.

- What is a literature review?

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

- You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

- Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

- Finalize your research question

- Think about relevant dates, geographies (and languages), methods, and conflicting points of view

- Conduct searches in the published literature via the identified databases

- Check to see if this topic has been covered in other discipline's databases

- Examine the citations of on-point articles for keywords, authors, and previous research (via references) and cited reference searching.

- Save your search results in a citation management tool (such as Zotero, Mendeley or EndNote)

- De-duplicate your search results

- Make sure that you've found the seminal pieces -- they have been cited many times, and their work is considered foundational

- Check with your professor or a librarian to make sure your search has been comprehensive

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individual sources and evaluate for bias, methodologies, and thoroughness

- Group your results in to an organizational structure that will support why your research needs to be done, or that provides the answer to your research question

- Develop your conclusions

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

- For example: Background, Current Practices, Critics and Proponents, Where/How this study will fit in

- Organize your citations and focus on your research question and pertinent studies

- Compile your bibliography

Note: The first four steps are the best points at which to contact a librarian. Your librarian can help you determine the best databases to use for your topic, assess scope, and formulate a search strategy.

Videos Tutorials about Literature Reviews

This 4.5 minute video from Academic Education Materials has a Creative Commons License and a British narrator.

Recommended Reading

- Last Updated: Oct 23, 2024 11:46 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Oct 18, 2024 11:42 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

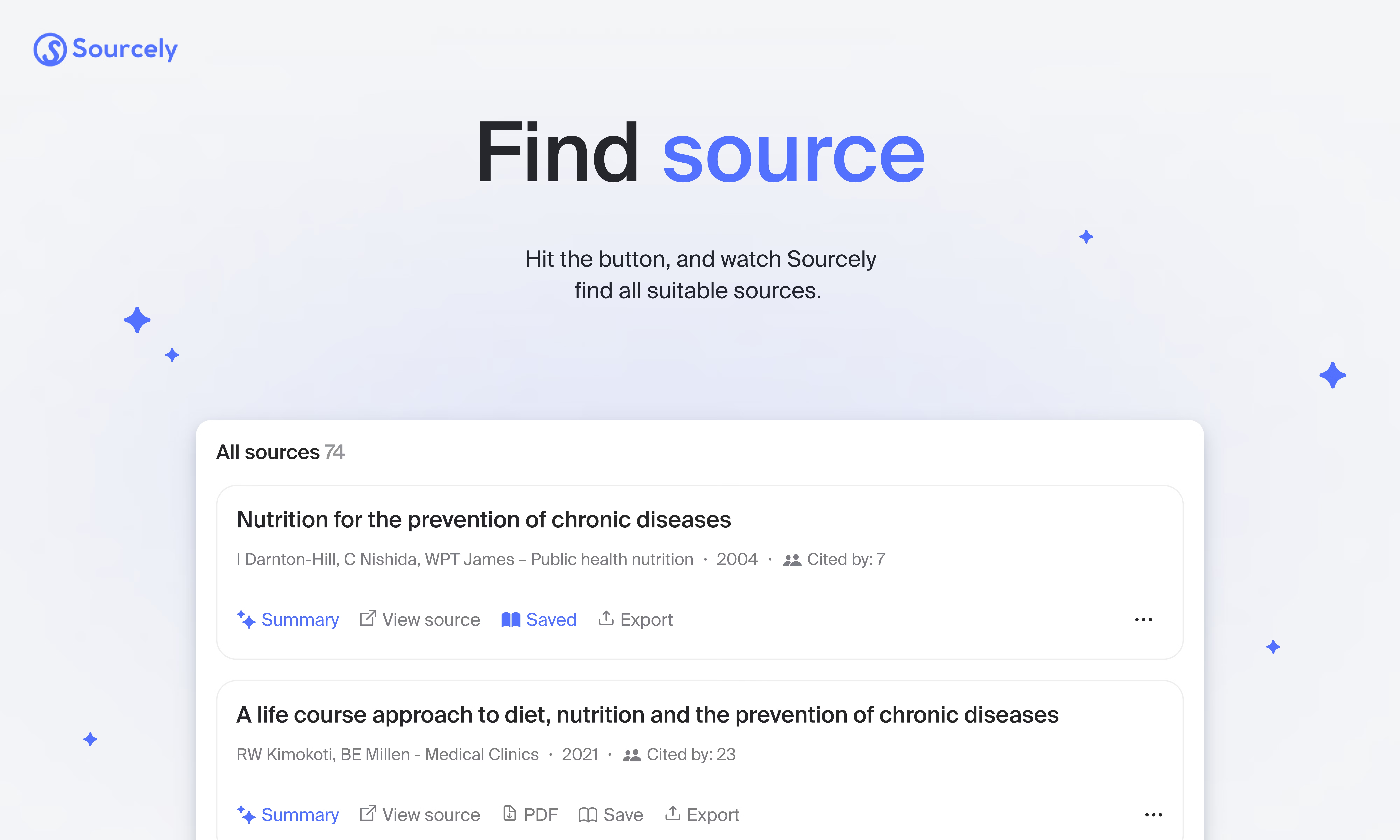

- Knowledge Base

- Get started

How to Write a Literature Review: Comprehensive Strategies and AI Tools

Discover how to craft an effective literature review using comprehensive strategies and AI tools. This guide offers step-by-step advice on organizing sources, synthesizing information, and leveraging AI to streamline the literature review process.

How to Write a Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide

A literature review is an essential part of academic research that involves summarizing, analyzing, and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. It serves as a critical component of the research process, helping you to build a solid foundation for your study by demonstrating your understanding of the current state of knowledge. Whether you are writing a thesis, dissertation, or research paper, a strong literature review not only establishes the foundation of your work but also helps to articulate the significance of your research by highlighting existing gaps, showcasing what has been done, and creating a clear context for your own research to fit into. This means that you are not just summarizing existing literature; you are actively engaging with it to justify the importance of your study and show where your research contributes to advancing the field.

A well-crafted literature review enables you to identify patterns, contradictions, and trends in the research, which ultimately helps you position your own work within the larger academic conversation. It showcases your ability to critically engage with the literature, assess the quality of existing studies, and synthesize information from a wide array of sources to present a cohesive overview. This process of summarizing, analyzing, and synthesizing is essential not just for understanding what has already been discovered, but for demonstrating to your readers and reviewers that you have a thorough grasp of the topic and are aware of the ongoing debates in the field.

In addition to identifying gaps and shaping the framework of your research, a literature review also plays an important role in avoiding redundancy. By thoroughly exploring existing studies, you can ensure that your research addresses new or underexplored areas, thereby making a unique contribution to the field. Whether you are conducting a systematic review to support a hypothesis or providing an overview to set the stage for new questions, an effective literature review is an invaluable tool that guides your entire research process.

In this guide, we will take you through the key steps to writing a comprehensive and well-structured literature review, from formulating a research question to evaluating sources, organizing themes, and writing up your findings. Our aim is to help you approach the task methodically and confidently, ensuring that your literature review not only meets academic standards but also adds significant value to your research project.

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a critical examination of the body of literature related to a particular research topic. It is not merely a summary of past research but a careful and deliberate selection of sources that collectively help shape the narrative of your research. The literature review goes beyond simply presenting what has been said on the topic; it contextualizes your research within the existing body of knowledge, showing how your work builds on, challenges, or fills gaps in the current understanding.

The purpose of a literature review is multifaceted. First and foremost, it demonstrates that you understand the key debates, discussions, and the broader landscape of scholarship in your field. This means critically engaging with the theories, findings, and methodologies of other researchers. By doing so, you establish the relevance of your own research, showing that you are informed about the topic and aware of the ongoing conversations that your study contributes to. Additionally, a literature review identifies gaps that your study aims to fill, helping to justify the need for your research.

A well-conceived literature review involves a careful balance of summarizing, analyzing, and synthesizing the information gathered from different sources. You need to present what each source says, evaluate its strengths and weaknesses, and relate it to the overall themes and direction of your study. This requires not only a clear understanding of each individual source but also an ability to draw connections between them, identify common threads, and highlight areas of disagreement or contention. By identifying patterns and drawing comparisons, you create a coherent picture of the existing research and set the stage for your own contributions.

Moreover, a good literature review should guide the reader through the evolution of thought on a topic, showcasing how ideas have developed over time and what questions remain unanswered. You can highlight how different scholars approach the same problem in various ways, thus adding nuance to your discussion. This is especially important for showing that you can critically assess the quality and credibility of existing studies. For example, you might point out methodological strengths in certain works and limitations in others, helping to make a case for the robustness of your approach.

Furthermore, the literature review isn't static—it's part of an ongoing process. New studies and data can emerge even as you conduct your research, which might influence the direction of your study. Therefore, a literature review also requires staying up-to-date with the latest developments, indicating that your research is relevant and responsive to the newest findings in the field. Engaging with the most current literature showcases that your work is informed and that it pushes the boundaries of what is already known.

In addition to these functions, a literature review can also help highlight diverse viewpoints. In some fields, debates and differing opinions are prevalent, and a strong literature review will not shy away from acknowledging these controversies. Instead, it will provide a balanced overview of varying perspectives, indicating the richness and complexity of the research landscape. By addressing these differing viewpoints, you add credibility to your own research, as it shows that you are not ignoring dissenting voices but rather are critically engaging with them to arrive at a well-supported conclusion.

A successful literature review is, therefore, a roadmap for your entire research project. It tells the reader where your research fits in, what it aims to address, and how it plans to do so. It is the bridge between what is already known and what your study aims to discover, and it sets up the foundation upon which your research is built.

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Literature Review

1. define your research question or topic.

The first step in creating a literature review is to clearly define your research question or topic. Knowing exactly what you are trying to explore will help you focus on finding the right sources. Your topic should be specific enough to limit the scope but broad enough to encompass significant research. Spend some time refining your research question, making sure it is neither too narrow nor too vague. A well-defined topic will serve as the guiding light throughout your literature review process, allowing you to determine what is relevant and what is not.

Consider breaking down your research question into smaller, manageable components. For instance, if your topic is broad, think of sub-questions that can help give your review a more detailed focus. Ask yourself questions like: What are the main concepts or variables involved? Are there specific populations or settings that you want to focus on? Defining these parameters early on will save you time later and will make your literature review more targeted and effective.

It is also helpful to frame your research question in a way that allows for a critical approach. Instead of simply asking "What is the impact of X on Y?" try asking questions that allow for exploration, comparison, or evaluation, such as "How does X compare to Y in terms of impact?" or "What factors influence the relationship between X and Y?" This type of question provides more scope for discussion and synthesis of multiple sources, which is essential for a robust literature review.

Furthermore, take time to review preliminary literature to ensure that your research question is feasible. If you find that there is too much information available, you may need to narrow your focus. Conversely, if there is too little information, you might need to broaden the scope or choose a different angle. The goal is to find a balance where your topic is sufficiently covered in existing literature, but still offers room for your unique contributions. This preparation step will make it much easier to navigate the subsequent phases of your literature review and will help ensure that your efforts are well-directed from the outset.

2. Search for Relevant Literature

The next step is to conduct a thorough search for relevant literature. Start by consulting academic databases such as Google Scholar, JSTOR, or PubMed to find credible sources. These platforms provide access to a wide variety of academic journals, books, and conference papers that are crucial for a well-rounded review. Make sure to use a combination of keywords, including synonyms and related concepts, to ensure you cover a broad range of research. Experiment with Boolean operators like AND, OR, and NOT to refine your searches effectively and obtain more precise results.

In addition to these databases, consider looking at specialized repositories that are specific to your field of study. For example, PsycINFO is an excellent resource for psychology-related research, while IEEE Xplore is perfect for those focusing on engineering and technology topics. Exploring multiple databases will ensure that your literature search is comprehensive and not restricted to a limited range of sources.

It's also helpful to set aside dedicated time to perform iterative searches. Often, initial searches may not yield all the information needed, and it's necessary to refine your keywords or try new combinations to discover more relevant literature. Keep an organized list of your search terms and the databases you have already explored, as this will help you avoid redundant work and ensure a systematic approach.

Consider keeping an organized list of your sources, including key information like the author, publication year, key arguments, and relevance to your topic. Tools like reference managers (e.g., Zotero, Mendeley) can be invaluable for this task. These tools allow you to store references, take notes, and easily format your bibliography, saving you considerable time in the long run. You may also want to create an annotated bibliography at this stage, summarizing the key points of each source and its relevance. This will help you stay organized and make it easier to integrate these sources into your literature review later.

Don't forget to check the reference lists of the articles you find particularly relevant. This technique, known as 'backward searching,' can lead you to other important studies that you might have missed during your initial search. Similarly, consider 'forward searching,' where you look at newer papers that have cited the article you're reading. This can help you find recent developments and ensure your literature review is up-to-date with the latest research in the field.

3. Evaluate and Select Sources

Not every source is worth including in your literature review. It is important to evaluate the credibility and relevance of the literature you find carefully. Look at several factors, including the methodology used, the reliability of data presented, the author's background and qualifications, and whether the research has been peer-reviewed. Understanding the research design, data collection, and analysis methods will help you determine whether the source is reliable and applicable to your work. Sources with rigorous methodologies are generally more trustworthy and contribute more valuable insights to your review.

Another critical aspect to consider is the publication date. Focus on sources that are up-to-date, particularly in rapidly evolving fields such as technology or medicine. However, older, foundational sources may still be valuable for providing historical context or explaining the evolution of theories over time. Balancing newer sources with seminal works can help provide a well-rounded understanding of your topic, demonstrating both breadth and depth in your literature review.

Additionally, consider the relevance of each source to your specific research question. Not all sources that mention your topic are equally valuable; prioritize those that directly contribute to the argument or context you are building. Ask yourself: Does this source address the specific aspects of my research question? Does it add new insights, support my thesis, or offer a contrasting viewpoint that is worth discussing? Being selective is key, as including too many irrelevant sources can dilute the impact of your literature review.

Evaluate the impact of the research within the field as well. Some studies have a greater influence and are frequently cited by other researchers. These high-impact sources are often critical to understanding the state of research on a topic. Tools like Google Scholar can help you determine how often a source has been cited, which can serve as an indicator of its significance. Including these well-cited sources in your literature review can strengthen the credibility of your arguments.

Don't forget to assess the author's background and potential biases. Knowing the author's credentials, institutional affiliations, and other publications can help you gauge the perspective from which the research is conducted. Authors affiliated with reputable academic institutions or organizations are generally more reliable, but it's still important to be aware of any potential biases that might affect the research. For example, industry-funded studies might be more likely to support outcomes favorable to the sponsor, which is something you should note in your evaluation.

Discard sources that do not meet these criteria. Sources with unclear methodologies, outdated information, questionable reliability, or that lack relevance to your specific research question should be excluded from your review. The goal is to include sources that provide robust, high-quality, and relevant information that helps build a solid foundation for your own research. By being diligent in this evaluation process, you ensure that your literature review is both comprehensive and trustworthy, ultimately supporting the credibility and value of your research project.

4. Identify Key Themes and Gaps

Once you have gathered your literature, start identifying common themes, areas of agreement, and areas of debate. Look closely at the different aspects of your topic that have been explored and note how various studies relate to one another. Are there consistent findings that point to a general consensus? Conversely, are there areas where researchers disagree, presenting conflicting evidence or different interpretations of the data? Recognizing these points of agreement and contention will help you create a balanced and nuanced literature review.

Are there patterns emerging across different studies? For instance, you might find that many researchers have focused on a particular population or context, which can indicate a trend or bias in the field. Highlighting these patterns can help you identify where the majority of research effort has been concentrated and where there may be gaps that need to be addressed. Also, pay attention to methodological similarities or differences—do researchers tend to use the same approaches, or are there contrasting methods that yield different results? Understanding these methodological patterns will give you insights into the strengths and weaknesses of the existing body of research.

Are there gaps or inconsistencies in the research? Identifying gaps in the literature is crucial, as it shows where further exploration is needed. Look for areas that have been overlooked or not sufficiently explored, and think about how your research could fill these voids. Gaps can include under-researched populations, overlooked variables, or even questions that have not been answered satisfactorily. Additionally, inconsistencies in findings are another important aspect to consider—are there studies that contradict one another? If so, why might these discrepancies exist? Could they be due to different methodologies, sample sizes, or interpretations? Highlighting these inconsistencies will not only help you position your work but also indicate the complexity of the topic.

Identifying these aspects will help you organize your review effectively and determine where your own research fits in. By clearly defining the key themes and gaps, you can create a literature review that does more than summarize existing research—it actively critiques and synthesizes the body of work, providing a meaningful context for your own study. This comprehensive approach will help demonstrate the value of your research and show that you are contributing to an ongoing scholarly conversation rather than simply reiterating what has already been done.

5. Structure Your Literature Review

A well-structured literature review typically follows a clear organizational pattern. There are several approaches you can choose from, depending on the nature of your research question and the body of literature available. One common method is the chronological approach , which organizes sources by publication date. This approach is particularly useful when you want to demonstrate how research has evolved over time or when there has been a significant shift in perspectives within your field. For example, you can show how early studies laid the groundwork for later research, or how advancements in technology influenced newer studies and methodologies.

Alternatively, a thematic approach groups sources by major topics, themes, or concepts rather than by time. This is especially useful when multiple studies address similar topics but from different angles or methodologies. By grouping sources thematically, you can highlight the different facets of your topic, such as recurring themes, points of agreement, and areas of debate. This approach can help you provide a more cohesive understanding of the literature, demonstrating how various aspects of the topic connect and interact with one another.

Another option is to use a methodological approach , which organizes sources based on the research methods used. This is particularly effective if you want to highlight how different research methods have contributed to the understanding of a topic. By categorizing studies based on qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods, you can analyze the strengths and limitations of each approach and show how different methodologies offer complementary insights. This type of structure can help underscore the robustness of your research question and position your study as filling a methodological gap in the literature.

You may also opt for a theoretical framework approach , where you organize your literature review based on the theoretical perspectives that guide the research. This approach is beneficial when discussing different theoretical lenses, such as social constructivism, positivism, or feminist theory, and how these theories shape the interpretation of findings. By using a theoretical approach, you can give your reader a better understanding of the various frameworks that inform the current body of literature and how your research contributes to or challenges these perspectives.

Make sure your structure makes it easy for readers to understand the evolution of research on your topic. Begin with broader concepts and foundational studies before narrowing down to more specific issues directly related to your research question. Providing a logical flow from general to specific allows your reader to grasp the bigger picture before delving into the finer details, thereby enhancing overall comprehension. Additionally, using subheadings for each section within your chosen structure can improve readability and help your readers navigate the review more effectively.

Regardless of the approach you choose, clarity and logical progression are key. The structure should guide your reader smoothly from one point to the next, helping them understand not only what has been studied but also why each piece of research is important. A well-structured literature review will naturally lead your reader to see the gaps that your research aims to fill, setting up a strong foundation for your research objectives and questions.

6. Write Your Review

Once you have an organized structure, start writing your literature review. Begin with an introduction that explains the scope of your review and outlines the main themes. The introduction should also include the reasons why this literature is relevant to your research, highlighting the gaps that your study will address. Establishing a clear rationale helps orient the reader and sets expectations for what is to come. Mention briefly the methodologies and key concepts that will be explored in your literature review to give the reader a roadmap of the discussion ahead.

In the body , summarize each source and discuss its contributions to the field, providing critical analysis where necessary. Each section of the body should cover a different theme or sub-topic, depending on the organizational approach you have chosen. For each source, consider summarizing the main arguments, but also add your own critical perspective on how the research contributes to the field and how it relates to other studies. Highlight the strengths of each study, such as innovative methodologies or significant findings, as well as the weaknesses, such as limited sample sizes or potential biases. This critical engagement not only adds depth to your literature review but also demonstrates your ability to think analytically about the literature.

Use subheadings to organize themes and make it easier for readers to follow. Subheadings also help to create a logical flow, making it clear how different areas of research link together. When transitioning between sections, use transitional sentences that help the reader understand how the literature evolves from one theme to the next. For instance, after discussing one theme, you could introduce the next by showing how it builds on or contrasts with the previous findings. This approach ensures that the reader is not only absorbing information but also understanding the connections between different pieces of research.

Be sure to include direct quotes where they add value, but use them sparingly and ensure that they are well-integrated into your own writing. Paraphrasing and summarizing are usually more effective because they demonstrate your understanding of the material. When you do use direct quotes, follow them up with a critical interpretation to explain why that particular point is important for your research.

Finish your literature review with a conclusion that ties everything together. Recap the main themes, highlight gaps, and explain how your research will address those gaps. A strong conclusion will reinforce the importance of your research and show that you have laid the foundation for your own work. In addition, the conclusion should reiterate how your findings contribute to the broader field of study and why addressing the identified gaps is essential. This not only establishes the value of your work but also helps the reader see the path forward for future research. If applicable, propose areas for further investigation that arise from your review, which will demonstrate a forward-thinking approach and highlight potential contributions beyond your immediate research.

7. Cite Your Sources Properly

Proper citation is crucial in a literature review. Using the correct citation style required by your institution or publication (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago) ensures that your work adheres to academic standards and makes it easy for readers to locate the original sources. The choice of citation style is often based on the discipline—for example, APA is commonly used in social sciences, while MLA is favored in the humanities. Familiarizing yourself with the nuances of your required style will help ensure that your citations are formatted correctly, which reflects positively on your attention to detail.

Correct citation not only adds credibility to your literature review but also helps you avoid plagiarism, which is a serious offense in academic work. Properly acknowledging the contributions of other researchers shows that you have engaged with the existing body of literature and gives credit where it is due. It also allows your readers to verify your sources, which strengthens the reliability of your arguments and demonstrates transparency in your research process. To maintain accuracy, make sure to cite not just direct quotes but also paraphrased ideas and any data or insights that are not your own.

To make this process more manageable, consider using reference managers like Zotero, EndNote, or Mendeley. These tools can help you organize your citations efficiently, allowing you to easily store, organize, and retrieve references. They also enable you to create bibliographies in the required style automatically, saving considerable time when finalizing your literature review. In addition, reference managers can be used to add notes to each reference, helping you keep track of why each source is relevant and how it contributes to your overall review.

Another important consideration is consistency. Ensure that all in-text citations and references in your bibliography follow the same format and meet the guidelines of the chosen citation style. Even minor inconsistencies, such as misplaced commas or incorrect italics, can detract from the professionalism of your work. Taking the time to double-check each citation for consistency will enhance the quality of your literature review.

It may also be beneficial to familiarize yourself with tools like citation guides or online resources (e.g., Purdue OWL) that provide examples and rules for specific citation styles. These resources can be particularly useful when you are unsure about how to cite unusual sources, such as government documents, personal interviews, or multimedia sources. Remember that accurate citation not only validates your work but also contributes to the academic community by making it easier for others to follow the research trail.

Tips for a Successful Literature Review

- Be selective : Don’t try to include everything you find. Focus on high-quality, relevant sources. Prioritize peer-reviewed journal articles, well-regarded books, and foundational texts that provide significant insights into your topic. Selectivity ensures that your literature review remains focused and directly contributes to your research goals.

- Stay organized : Keep a detailed record of your searches and sources. Annotated bibliographies are a useful tool. Tools like Mendeley, EndNote, or Zotero can help you keep your sources organized and allow you to easily insert citations as you write. Creating a system to tag or categorize your sources can make it easier to retrieve information when needed.

- Balance summary with critical analysis : Your literature review should not be a mere collection of summaries. Aim to synthesize and analyze, showing the relationships between different studies. Make connections between sources by highlighting how they build on, support, or contradict each other. This approach will help to provide depth to your review and illustrate the broader conversations happening within your research field.

- Revise and refine : Writing a literature review is an iterative process. Revise your draft to ensure it flows logically and effectively communicates your points. Revisiting and refining the organization of your review can help ensure that your argument builds logically and that your findings are presented in a compelling manner.

- Use mind maps or charts : Visual tools such as mind maps or thematic charts can help you organize ideas and see relationships among various studies more clearly. These tools are particularly useful for identifying themes, gaps, and patterns across multiple sources, and they can make the writing process smoother by providing a visual roadmap of your arguments.

- Keep track of evolving research : Stay updated on new publications even as you are working on your literature review. Use alerts on academic databases to receive notifications of new studies related to your topic. Incorporating the most recent research shows that your review is current and relevant, which can be especially important in rapidly changing fields.

- Consult with peers or advisors : Don’t hesitate to seek feedback on your literature review from peers, advisors, or mentors. They may provide insights or identify gaps that you’ve missed, helping to strengthen the quality of your work. Peer feedback is also helpful for identifying areas where the flow or clarity of your review could be improved.

- Define and refine your scope : Clearly define the scope of your literature review at the outset. Are you focusing on a specific time period, demographic, methodology, or geographic area? Being explicit about your scope will make it easier to decide which sources to include and which to exclude, ensuring that your review remains focused and relevant.

- Develop a critical voice : Don’t simply report what other studies have said; evaluate their contributions. What are the strengths and weaknesses of the methodologies used? Are the conclusions justified by the data? Developing a critical voice means that you are actively engaging with the literature and providing your own interpretation rather than passively summarizing.

- Be mindful of biases : Evaluate potential biases in the literature, such as funding sources, publication bias, or the author's background. Addressing these biases in your literature review adds depth and shows your ability to critically engage with the literature, enhancing the credibility of your work.

- Link to your research question : Throughout your review, continually link back to your own research question. Explicitly state how each study relates to or informs your research. This makes your literature review more cohesive and ensures that every source you include serves a purpose in building the foundation for your study.

Final Thoughts

Writing a literature review can feel overwhelming, especially if you’re new to academic research. However, by breaking it down into manageable steps and staying organized, you can create a literature review that provides a solid foundation for your research. Remember, the goal is not just to summarize existing studies but to synthesize the information and create a compelling narrative that supports your research question.

It's important to remember that a literature review is not a one-time task but rather an iterative process. You may need to revisit your review multiple times as new studies emerge or as your research takes on a clearer direction. Each iteration allows you to refine your synthesis, making your arguments stronger and your narrative more compelling. Flexibility is key—be open to changing your perspective if new evidence suggests a better approach or reveals a different gap in the literature.

Another valuable approach is to continuously question the relevance of the literature you include. Ask yourself: Does this source add real value to my argument? Does it strengthen the rationale behind my research question? By being selective and ensuring that each source is directly relevant to your objectives, you can create a focused and impactful literature review. This level of discernment is what differentiates a well-crafted literature review from one that simply lists sources without a cohesive purpose.

Don't underestimate the power of collaboration during the literature review process. Discussing your findings, interpretations, and gaps with peers or mentors can provide new insights that you may not have considered. Feedback from colleagues can help pinpoint areas that need more depth or clarify arguments that are not as strong. Collaboration is particularly helpful when synthesizing diverse viewpoints, as it allows you to gain a different perspective on the same body of literature, adding richness to your review.

Additionally, managing your time effectively is crucial. Set milestones for each stage of your literature review—from identifying your research question to finalizing your written review. Breaking the task into smaller, time-bound goals will not only make it more manageable but will also ensure that you stay on track and do not become overwhelmed by the volume of information. Time management also allows you to allocate periods for revising and refining, which are critical to producing a polished final product.

Finally, remember that a well-written literature review does more than serve as a backdrop for your research; it sets the stage for everything that follows. By establishing a clear context, identifying gaps, and linking existing knowledge to your research objectives, your literature review becomes the foundation that justifies your study. The more effort you put into crafting a cohesive and thorough review, the more effectively it will support your research, helping to establish your credibility as a scholar and making a meaningful contribution to your field.

With practice and careful planning, your literature review can become a powerful part of your academic writing, adding depth and context to your work.

Sourcely weekly newsletters

Cut through the AI noise with a focus on Students! Subscribe for 3 Student AI tools every week to accelerate your academic career.

Join Sourcely weekly newsletters

Ready to get started.

Start today and explore all features with up to 300 characters included. No commitment needed — experience the full potential risk-free!

Check out our other products

Discover cutting-edge research with arXivPulse: Your AI-powered gateway to scientific papers

Don't stress about deadlines. Write better with Yomu and simplify your academic life.

Welcome to Sourcely! Our AI-powered source finding tool is built by students for students, and this approach allows us to create a tool that truly understands the needs of the academic community. Our student perspective also enables us to stay up-to-date with the latest research and trends, and our collaborative approach ensures that our tool is continually improving and evolving.

- Refund Policy

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Friends of Sourcely

- ArXiv Pulse

- Semantic Reader

- AI Tools Inc

© 2024 Sourcely

Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- Six Steps to Writing a Literature Review

- Finding Articles

- Try A Citation Manager

- Avoiding Plagiarism

Selecting a Research Topic

The first step in the process involves exploring and selecting a topic. You may revise the topic/scope of your research as you learn more from the literature. Be sure to select a topic that you are willing to work with for a considerable amount of time.

When thinking about a topic, it is important to consider the following:

Does the topic interest you?

Working on something that doesn’t excite you will make the process tedious. The research content should reflect your passion for research so it is essential to research in your area of interest rather than choosing a topic that interests someone else. While developing your research topic, broaden your thinking and creativity to determine what works best for you. Consider an area of high importance to your profession, or identify a gap in the research. It may take some time to narrow down on a topic and get started, but it’s worth the effort.

Is the Topic Relevant?

Be sure your subject meets the assignment/research requirements. When in doubt, review the guidelines and seek clarification from your professor.

What is the Scope and Purpose?

Sometimes your chosen topic may be too broad. To find direction, try limiting the scope and purpose of the research by identifying the concepts you wish to explore. Once this is accomplished, you can fine-tune your topic by experimenting with keyword searches our A-Z Databases until you are satisfied with your retrieval results.

Are there Enough Resources to Support Your Research?

If the topic is too narrow, you may not be able to provide the depth of results needed. When selecting a topic make sure you have adequate material to help with the research. Explore a variety of resources: journals, books, and online information.

Adapted from https://jgateplus.com/home/2018/10/11/the-dos-of-choosing-a-research-topic-part-1/

Why use keywords to search?

- Library databases work differently than Google. Library databases work best when you search for concepts and keywords.

- For your research, you will want to brainstorm keywords related to your research question. These keywords can lead you to relevant sources that you can use to start your research project.

- Identify those terms relevant to your research and add 2-3 in the search box.

Now its time to decide whether or not to incorporate what you have found into your literature review. E valuate your resources to make sure they contain information that is authoritative, reliable, relevant and the most useful in supporting your research.

Remember to be:

- Objective : keep an open mind

- Unbiased : Consider all viewpoints, and include all sides of an argument, even ones that don't support your own

Criteria for Evaluating Research Publications

Significance and Contribution to the Field

• What is the author’s aim?

• To what extent has this aim been achieved?

• What does this text add to the body of knowledge? (theory, data and/or practical application)

• What relationship does it bear to other works in the field?

• What is missing/not stated?

• Is this a problem?

Methodology or Approach (Formal, research-based texts)

• What approach was used for the research? (eg; quantitative or qualitative, analysis/review of theory or current practice, comparative, case study, personal reflection etc…)

• How objective/biased is the approach?

• Are the results valid and reliable?

• What analytical framework is used to discuss the results?

Argument and Use of Evidence

• Is there a clear problem, statement or hypothesis?

• What claims are made?

• Is the argument consistent?

• What kinds of evidence does the text rely on?

• How valid and reliable is the evidence?

• How effective is the evidence in supporting the argument?

• What conclusions are drawn?

• Are these conclusions justified?

Writing Style and Text Structure

• Does the writing style suit the intended audience? (eg; expert/non-expert, academic/non- academic)

• What is the organizing principle of the text?

- Could it be better organized?

Prepared by Pam Mort, Lyn Hallion and Tracey Lee Downey, The Learning Centre © April 2005 The University of New South Wales.

Analysis: the Starting Point for Further Analysis & Inquiry

After evaluating your retrieved sources you will be ready to explore both what has been found and what is missing . Analysis involves breaking the study into parts, understanding each part, assessing the strength of evidence, and drawing conclusions about its relationship to your topic.

Read through the information sources you have selected and try to analyze, understand and critique what you read. Critically review each source's methods, procedures, data validity/reliability, and other themes of interest. Consider how each source approaches your topic in addition to their collective points of intersection and separation . Offer an appraisal of past and current thinking, ideas, policies, and practices, identify gaps within the research, and place your current work and research within this wider discussion by considering how your research supports, contradicts, or departs from other scholars’ research and offer recommendations for future research.

Top 10 Tips for Analyzing the Research

- Define key terms

- Note key statistics

- Determine emphasis, strengths & weaknesses

- Critique research methodologies used in the studies

- Distinguish between author opinion and actual results

- Identify major trends, patterns, categories, relationships, and inconsistencies

- Recognize specific aspects in the study that relate to your topic

- Disclose any gaps in the literature

- Stay focused on your topic

- Excluding landmark studies, use current, up-to-date sources

Prepared by the fine librarians at California State University Sacramento.

Synthesis vs Summary

Your literature review should not simply be a summary of the articles, books, and other scholarly writings you find on your topic. It should synthesize the various ideas from your sources with your own observations to create a map of the scholarly conversation taking place about your research topics along with gaps or areas for further research.

Bringing together your review results is called synthesis. Synthesis relies heavily on pattern recognition and relationships or similarities between different phenomena. Recognizing these patterns and relatedness helps you make creative connections between previously unrelated research and identify any gaps.

As you read, you'll encounter various ideas, disagreements, methods, and perspectives which can be hard to organize in a meaningful way. A synthesis matrix also known as a Literature Review Matrix is an effective and efficient method to organize your literature by recording the main points of each source and documenting how sources relate to each other. If you know how to make an Excel spreadsheet, you can create your own synthesis matrix, or use one of the templates below.

Because a literature review is NOT a summary of these different sources, it can be very difficult to keep your research organized. It is especially difficult to organize the information in a way that makes the writing process simpler. One way that seems particularly helpful in organizing literature reviews is the synthesis matrix. Click on the link below for a short tutorial and synthesis matrix spreadsheet.

- Literature Review and Synthesis

- Lit Review Synthesis Matrix

- Synthesis Matrix Example

A literature review must include a thesis statement, which is your perception of the information found in the literature.

A literature review:

- Demonstrates your thorough investigation of and acquaintance with sources related to your topic

- Is not a simple listing, but a critical discussion

- Must compare and contrast opinions

- Must relate your study to previous studies

- Must show gaps in research

- Can focus on a research question or a thesis

- Includes a compilation of the primary questions and subject areas involved

- Identifies sources

https://custom-writing.org/blog/best-literature-review

Organizing Your Literature Review

The structure of the review is divided into three main parts—an introduction, body, and the conclusion.

Introduction

Discuss what is already known about your topic and what readers need to know in order to understand your literature review.

- Scope, Method, Framework: Explain your selection criteria and similarities between your sources. Be sure to mention any consistent methods, theoretical frameworks, or approaches.

- Research Question or Problem Statement: State the problem you are addressing and why it is important. Try to write your research question as a statement.

- Thesis : Address the connections between your sources, current state of knowledge in the field, and consistent approaches to your topic.

- Format: Describe your literature review’s organization and adhere to it throughout.

Body

The discussion of your research and its importance to the literature should be presented in a logical structure.

- Chronological: Structure your discussion by the literature’s publication date moving from the oldest to the newest research. Discuss how your research relates to the literature and highlight any breakthroughs and any gaps in the research.

- Historical: Similar to the chronological structure, the historical structure allows for a discussion of concepts or themes and how they have evolved over time.

- Thematic: Identify and discuss the different themes present within the research. Make sure that you relate the themes to each other and to your research.

- Methodological: This type of structure is used to discuss not so much what is found but how. For example, an methodological approach could provide an analysis of research approaches, data collection or and analysis techniques.

Provide a concise summary of your review and provide suggestions for future research.

Writing for Your Audience

Writing within your discipline means learning:

- the specialized vocabulary your discipline uses

- the rhetorical conventions and discourse of your discipline

- the research methodologies which are employed

Learn how to write in your discipline by familiarizing yourself with the journals and trade publications professionals, researchers, and scholars use.

Use our Databases by Title to access:

- The best journals

- The most widely circulated trade publications

- The additional ways professionals and researchers communicate, such as conferences, newsletters, or symposiums.

- << Previous: What is a Literature Review?

- Next: Finding Articles >>

- Last Updated: Jan 18, 2024 1:14 PM

- URL: https://niagara.libguides.com/litreview

Literature Reviews

- Tools & Visualizations

- Literature Review Examples

- Videos, Books & Links

Business & Econ Librarian

Click to Chat with a Librarian

Text: (571) 248-7542

What is a literature review?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area. Often part of the introduction to an essay, research report or thesis, the literature review is literally a "re" view or "look again" at what has already been written about the topic, wherein the author analyzes a segment of a published body of knowledge through summary, classification, and comparison of prior research studies, reviews of literature, and theoretical articles. Literature reviews provide the reader with a bibliographic history of the scholarly research in any given field of study. As such, as new information becomes available, literature reviews grow in length or become focused on one specific aspect of the topic.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but usually contains an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, whereas a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. The literature review might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. Depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

A literature review is NOT:

- An annotated bibliography – a list of citations to books, articles and documents that includes a brief description and evaluation for each citation. The annotations inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy and quality of the sources cited.

- A literary review – a critical discussion of the merits and weaknesses of a literary work.

- A book review – a critical discussion of the merits and weaknesses of a particular book.

- Teaching Information Literacy Reframed: 50+ Framework-Based Exercises for Creating Information-Literate Learners

- The UNC Writing Center – Literature Reviews

- The UW-Madison Writing Center: The Writer’s Handbook – Academic and Professional Writing – Learn How to Write a Literature Review

What is the difference between a literature review and a research paper?

The focus of a literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions, whereas academic research papers present and develop new arguments that build upon the previously available body of literature.

How do I write a literature review?

There are many resources that offer step-by-step guidance for writing a literature review, and you can find some of them under Other Resources in the menu to the left. Writing the Literature Review: A Practical Guide suggests these steps:

- Chose a review topic and develop a research question

- Locate and organize research sources

- Select, analyze and annotate sources

- Evaluate research articles and other documents

- Structure and organize the literature review

- Develop arguments and supporting claims

- Synthesize and interpret the literature

- Put it all together

What is the purpose of writing a literature review?

Literature reviews serve as a guide to a particular topic: professionals can use literature reviews to keep current on their field; scholars can determine credibility of the writer in his or her field by analyzing the literature review.

As a writer, you will use the literature review to:

- See what has, and what has not, been investigated about your topic

- Identify data sources that other researches have used

- Learn how others in the field have defined and measured key concepts

- Establish context, or background, for the argument explored in the rest of a paper

- Explain what the strengths and weaknesses of that knowledge and ideas might be

- Contribute to the field by moving research forward

- To keep the writer/reader up to date with current developments in a particular field of study

- Develop alternative research projects

- Put your work in perspective

- Demonstrate your understanding and your ability to critically evaluate research in the field

- Provide evidence that may support your own findings

- Next: Tools & Visualizations >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 3:43 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.library.american.edu/literaturereview

University Library

Write a literature review.

- Examples and Further Information

1. Introduction

Not to be confused with a book review, a literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources (e.g. dissertations, conference proceedings) relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, providing a description, summary, and critical evaluation of each work. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

2. Components

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Literature reviews should comprise the following elements:

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review

- Division of works under review into categories (e.g. those in support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative theses entirely)

- Explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

In assessing each piece, consideration should be given to:

- Provenance—What are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity—Is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness—Which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value—Are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

3. Definition and Use/Purpose

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

The literature review itself, however, does not present new primary scholarship.

- Next: Examples and Further Information >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

- Learn How to Use the Library

- Providers & Employees

- Research Help

- All Research Guides

Conducting Literature Reviews

- About Literature Reviews

Process Overview

Step 1: the research question, step 2: search the literature, step 3: manage results, step 4: synthesize information, step 5: write the review.

- Additional Resources

- APA Style (7th ed.) This link opens in a new window

Like research, writing a literature review is an iterative process. Here is a very broad example of the process:

- Frame the research question and determine the scope of the literature review

- Search relevant bodies of literature

- Manage and organize search results

- Synthesize the literature

- Write an assessment of the literature

The initial steps should already be familiar to you, as they parallel steps of the research process you have used before.

Research questions, like topics, must be specific and focused so that you can 1) search for materials to address the question, and 2) write a literature review that is manageable in scope and purpose.

Developing a research question is the next logical step after selecting and then narrowing a topic. It is important to have a research question because it focuses your next step in the literature review process: searching. As Booth (2008) explains in The Craft of Research : "If a writer asks no specific question worth asking, he can offer no specific answer worth supporting. And without an answer to support, he cannot select from all the data he could find on a topic to just those relevant to his answer" (p. 41).

Once you have selected and narrowed your topic, ask yourself questions about the topic's:

- History (Is is part of a large context? What is its own internal history? How has it changed over time?)

- Structure and composition (Is it part of a larger system/structure? How do its parts fit together?)

- Categorization (Can you compare/contrast it with similar topics? Does it belong to a group of similar kinds?)

You can also:

- Turn positive questions into negative ones by focusing on "nots" (why didn't this happen? why isn't this significant in context?) or by contrasting differences

- Ask "what if" speculative questions (what if your topic disappeared? Was put in a different context?)

- Ask questions suggested by your initial background research, such as those that build on agreement (Author X made a persuasive point...) or reflect disagreement (Author Y's conclusion doesn't account for this contextual element...)

You may find that you need to reframe or revise your question as you continue through the literature process. That's ok! Remember, the literature review process is iterative.

For more detailed information on forming and evaluating research questions, see these books available to order through ILL from OhioLINK.

- OhioLINK Library Catalog This link opens in a new window Catalog of books and other materials held in Ohio college and university libraries.

More Resources

- The Research Process Get help with selecting and narrowing a topic.

General guidance on where to search for sources:

- Where to Find Sources

Subject-specific guidance on where to search for sources:

- Evidence-Based Practice by Mike Jundi Last Updated Jan 26, 2023 26 views this year

- Finding Legislation, Data, & Statistics by Mike Jundi Last Updated Dec 5, 2023 23 views this year

- Nursing Research by Mike Jundi Last Updated Jan 18, 2024 84 views this year

- RAD 112 - Introduction to Radiography by Mike Jundi Last Updated Jan 18, 2024 26 views this year

- Social Work Resources by Mike Jundi Last Updated Dec 5, 2023 17 views this year

How to search for sources by developing a search strategy:

- How to Search for Sources

General guidance on using catalogs and databases:

- Basic Library Tutorials by Mike Jundi Last Updated Jan 18, 2024 637 views this year

Research management involves collecting, organizing, and citing.

Research management is also based largely on personal preference. Do you have a system that works for you? Great! If you aren't used to research management and/or don't have an effective system in place, you have options.

- Do-it-yourself: maintain your resources on your computer's hard drive or on the cloud (Microsoft OneDrive, Google Drive, DropBox)

- Use a free research management software (Mendeley, Zotero, EndNote)

Regardless of what system you use, it is necessary to keep track of the these elements:

- The literature you found (Did you find full text in a PDF? Save it. Did you find a record in a database, but need to request the article? Save the permalink to the record.)

- The full APA citation for the literature

- An easy way to track results you've found in databases is to create folders

Finally, you will need a note-taking system that will help you record the key concepts from the literature when you read and synthesize it. If you already have one, great! If you struggle with note-taking, see the links below.

What is synthesis?

Synthesizing information is much the opposite of analyzing information. When you read an article or book, you have to pull out specific concepts from the larger document in order to understand it. This is analyzing.

When you synthesize information, you take specific concepts and consider them together to understand how they compare/contrast and how they relate to one another. In other terms, synthesis involves combining multiple elements to create a whole. In regard to literature reviews, the elements refer to the findings from the literature you've gathered. The whole then becomes your conclusion(s) about those findings.

How do I synthesize information?

Note: This stage in the literature review process is as iterative and personal as any other. These steps offer a guideline, but do what works for you best.

- This is where you really decide if you want to read specific materials

- If you have gathered a substantial amount of literature and reading all of it would prove overwhelming, read the abstracts to get a better idea of the content, then select the materials that would best support your review

- Describe and analyze the findings (What were the results? How did the authors get these results? What are the impacts? Etc.)

- Identify the key concepts

- Compare and contrast findings, concepts, conclusions, methods, etc.

- Evaluate the quality and significance of findings, concepts, conclusions, methods, etc.

- Interpret the findings, concepts, conclusions, methods, etc. in the context of your research question

- This is the step where your synthesis of the information will lead to logical conclusions about that information

- These conclusions should speak directly to your research question (i.e. your question should have an answer)

Visit the link below for helpful resources on note-taking:

- Other Helpful Tips: Note-Taking & Proofreading

Writing style

You are expected to follow APA Style in your writing. Visit this guide for an introduction, tips, and tutorials:

- APA Style Resources (7th ed.) by Mike Jundi Last Updated Jan 13, 2023 348 views this year

The structure and flow of your literature review should be logical and should reflect the synthesis you have done.

A common pitfall for students is using an author-driven structure , which might look something like this:

- Introduction

- Author 1 says x

- Author 2 says y

- Author ∞ says...

Why doesn't the author-driven structure work?

- Leans toward listing or summarizing information

- Doesn't illustrate synthesis of information (all of the findings are listed based on where they came from, not their meaning, impact, or significance)

What structures do work? The APA suggests three structures for literature reviews:

- Theme-based (group studies based on common themes or concepts present)

- Methodology-based (group studies based on the methodologies used)

- Chronological (group studies based on the historical developments in the field)

Theme-based structure

The theme-based structure is applicable to most bodies of literature you might gather. It may look like this:

- Concept x from author 1

- Concept a from author 5

- Concept y from author 2

- Concepts…

Why does the them-based structure work better?

- It avoids listing information

- It clearly shows the synthesis that occurred

- It illustrates the connections between concepts and the significance of particular concepts

- << Previous: About Literature Reviews

- Next: Additional Resources >>

- Last Updated: Oct 13, 2022 3:08 PM

- URL: https://aultman.libguides.com/literaturereviews

Aultman Health Sciences Library

Aultman Education Center, C2-230, 2600 Sixth St SW, Canton, OH 44710 | 330-363-5000 | [email protected]

- Franklin University |

- Help & Support |

- Locations & Maps |

- | Research Guides

To access Safari eBooks,

- Select not listed in the Select Your Institution drop down menu.

- Enter your Franklin email address and click Go

- click "Already a user? Click here" link

- Enter your Franklin email and the password you used to create your Safari account.

Continue Close

Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Framing the Literature Review

Literature Review Process

- Mistakes to Avoid & Additional Help

The structure of a literature review should include the following :

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories (e.g. works that support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely),

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?