Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- louisville.edu

- PeopleSoft HR

- PeopleSoft Campus Solutions

- PeopleSoft Financials

- Business Ops

- Cardinal Careers

- Undergraduate

- International

- Online Learning

University of Louisville Writing Center

- University Writing Center FAQs

- Virtual Writing Center FAQs

- HSC Writing Center FAQs

- Writing FAQs

- Handouts and Videos

- Graduate Student Writing

- Spring Dissertation Writing Retreat

- Graduate Student Writing Workshops

- Graduate Student Writing Group

- Writing Groups

- Accessibility and Accommodations

- The University Writing Center and Your Students

- Request a Presentation about the University Writing Center

- Resources for Teaching Writing

- The Writing Center and Your Writing

- Faculty and Graduate Student Writing Group

- University Writing Center Mission Statement

- Meet Our Staff

- Statement on Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity

- Research at the University Writing Center

- How I Write Blog Posts

- Our Community Writing Values and Approaches

- Community Writing Internships and Volunteering

- Family Scholar House

- Western Branch Library

- How can I make myself a stronger writer?

- What makes college writing different than the writing I’ve done up to this point?

- How are the papers I'm asked to write in my major different from those in English 101, 102, and 105 courses?

- What can I do if I don’t completely understand the writing assignment?

- I want to get started writing early, but how do I begin?

- How do I get started writing a personal statement?

- I have a lot to say, but how can I organize my thoughts?

- How can I learn how to write in a new genre (for example, personal statement, resume, or literature review)?

- How do I expand a rough draft to make it meet the assignment’s length requirement?

- How can I find good sources for my research paper?

- What are some strategies for working sources into my research paper?

- What is the difference between quotation, paraphrase, and summary?

- How can I revise my draft if it doesn’t seem to “flow”?

- What does my teacher mean by “substantial revision?”

- How do I write an essay that makes an “argument”?

- How can I avoid plagiarizing?

- What are some strategies for improving my grammar and punctuation?

- How can I format my document properly in Word, PowerPoint or Excel?

- How should I approach writing a literature review at the graduate level?

- / Resources for Students

- / Writing FAQs

- / How should I approach writing a literature review at the graduate level?

What is the purpose of a Literature Review? For a graduate student the purpose of academic writing changes from what it was as an undergraduate. Where undergraduates often write to demonstrate a mastery of existing knowledge, graduate students are considered scholars and move toward creating new knowledge. Writing in graduate school, then, focuses on communicating that new knowledge to others in their field. In order to communicate this knowledge to other scholars, however, it also necessary to explain how that knowledge engages ongoing scholarly conversations in the field.

A literature review is a common genre for many types of writing you’ll have to do as a graduate student and scholar. Not only do dissertations contain literature reviews, but most articles and grant proposals have some form of literature review included in them. The reason the literature review is so prevalent in scholarly writing is that it functions as an argument about how your project fits in the ongoing scholarly conversation in your field and justifies your project.

A successful literature review does more than list the research that has preceded your work. A literature review is not simply a summary of research. Your literature review must not only demonstrate that you understand important conversations and debates surrounding your project and your position in regard to the conversations, but it must also create an argument as to why your work is relevant to your field of study. In order to create such an argument you must evaluate the relevant research, describing its strengths and weaknesses in relation to your project. You must then explain how your project will build on the work of other researchers, and fill the scholarly gaps left by other researchers. What is typically included in a Literature Review and how do I start?

To show how your project joins an existing scholarly conversation you need to provide readers with the necessary background to understand your research project and persuade them that your intervention in the scholarly conversation is necessary. The first step is to evaluate and analyze the scholarship that is key to understanding your work. The scholarship you evaluate may include previous research on similar topics, theoretical concepts and perspectives, or methodological approaches. Evaluating existing research means more than just summarizing the scholar’s main point. You will also want to assess the strengths and limits of the writer’s project and approach. Questions to consider as you read include: What problems or issues is the writer exploring? What position does the writer take? How is the writer intervening in an ongoing conversation? Where does the writer leave the issue?

Once you have evaluated the research of others, you need to consider how to integrate ideas from other scholars with your ideas and research project. You will also need to show your readers which research is relevant to understanding your project and explain how you position your work in relationship to what has come before your project. In order to do this, it may be helpful to think about the nature of your research project. Not all research has the same purpose. For example, your research project may focus on extending existing research by applying it in a new context. Or you may be questioning the findings of existing research, or you may be pulling together two or more previously unconnected threads of research. Or your project may be bringing a new theoretical lens or interpretation to existing questions. The focus of your research project will determine the kind of material you need to include in your literature review. What are some approaches for organizing a Literature Review? In the first part of a literature review you typically establish several things. You should define or identify your project and briefly point out overall trends in what has been published about the topic – conflicts, gaps in research, foundational research or theory, etc. You should also establish your position – or argument - for the project and the organization of the review.

In the body of the literature review, consider organizing the research and theory according a particular approach. For example, you could discuss the research chronologically. Or you could organize the research thematically, around key ideas or terms or theoretical approaches. Your literature review may include definitions of key terms and the sources from which they are drawn, descriptions of relevant debates in the field, or a description of the most current thinking on your topic.

You will also want to provide clear transitions and strong organizing sentences at the start of sections or paragraphs. You may find it helpful to divide the body of the review up into individual sections with individual subheadings. As you summarize and evaluate studies or articles keep in mind that each article should not necessarily get the same amount of attention. Some scholarship will be more central to your project and will therefore have to be discussed at more length. There also may be some scholarship that you choose not to include, so you might need to explain those decisions. At every turn, you want to keep in mind how you are making the case for how your research will advance the ongoing scholarly conversation. What can the Writing Center do to help? It can sometimes be difficult, after reading pages and pages of research in your field, to step back from the work and decide how best to approach your literature review. Even before you begin to write you may find a consultation in the Writing Center will help you plan out your literature review. Consultants at the Writing Center are experienced in working with scholars to help them reflect on and organize their work in a literature review so it creates the argument for your project. Make an appointment to work with us on your focus and organization even before you begin to write. We are also able to help you by reading and responding to your drafts or to help with issues of documentation. We can help you understand the genre conventions of the literature review, work through revisions, and help you learn how to edit your own work. We recommend that you come in early to give yourself enough time to work through any problems that may come up as you write.

Five Ideas on Working with the Writing Center Sep 04, 2024

Conceptualizing Trauma-Informed Consulting in the University Writing Center Apr 17, 2024

Creating Art: A Painter’s Journey Into the World of Writing Mar 25, 2024

Getting Comfortable with Directive Practices in the Writing Center Mar 08, 2024

International Mother Language Day 2024 Mar 04, 2024

University and High School Writing Centers Feb 26, 2024

UofL Writing Center Blog - More…

University Writing Center

Ekstrom Library 132

Kornhauser Library 218

University of Louisville

Louisville, Kentucky 40292

Ekstrom Library

M 9 am - 5 pm

T, W, Th 9 am - 7 pm

F 9 am - 4 pm

Closed on student breaks and holidays

(502) 852-2173

Social Media

Work With Us

Private Coaching

Done-For-You

Short Courses

Client Reviews

Free Resources

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Q uality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Learn More About Lit Review:

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

5 Signs You Need A Dissertation Helper

Discover the 5 signs that suggest you need a dissertation helper to get unstuck, finish your degree and get your life back.

Writing A Literature Review: 4 Time-Saving Hacks

🎙️ PODCAST: Ace The Literature Review 4 Time-Saving Tips To Fast-Track Your Literature...

Research Question 101: Everything You Need To Know

Learn what a research question is, how it’s different from a research aim or objective, and how to write a high-quality research question.

Research Question Examples: The Perfect Starting Point

See what quality research questions look like across multiple topic areas, including psychology, business, computer science and more.

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

- Library Catalogue

Literature reviews for graduate students

On this page, what is a literature review, literature review type definitions, literature review protocols and guidelines, to google scholar, or not to google scholar, subject headings vs. keywords, keeping track of your research, project management software, citation management software, saved searches.

Related guides:

- Systematic, scoping, and rapid reviews: An overview

- Academic writing: what is a literature review , a guide that addresses the writing and composition aspect of a literature review

- Media literature reviews: how to conduct a literature review using news sources

- Literature reviews in the applied sciences

- Start your research here , literature review searching, mainly of interest to newer researchers

For more assistance, please contact the Liaison Librarian in your subject area .

Most generally, a literature review is a search within a defined range of information source types, such as, for instance, journals and books, to discover what has been already written about a specific subject or topic. A literature review is a key component of almost all research papers. However, the term is often applied loosely to describe a wide range of methodological approaches. A literature review in a first or second year course may involve browsing the library databases to get a sense of the research landscape in your topic and including 3-4 journal articles in your paper. At the other end of the continuum, the review may involve completing a comprehensive search, complete with documented search strategies and a listing of article inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the most rigorous format - a Systematic Review - a team of researchers may compile and review over 100,000 journal articles in a project spanning one to two years! These are out of scope for most graduate students, but it is important to be aware of the range of types of reviews possible.

One of the first steps in conducting a lit review is thus to clarify what kind of review you are doing, and its associated expectations.

Factors determining review approach are varied, including departmental/discipline conventions, granting agency stipulations, evolving standards for evidence-based research (and the corollary need for documented, replicable search strategies), and available time and resources.

The standards are also continually evolving in light of changing technology and evidence-based research about literature review methodology effectiveness. The availability of new tools such as large-scale library search engines and sophisticated citation management software continues to influence the research process.

Some specific types of lit reviews types include systematic reviews , scoping reviews , realist reviews , narrative reviews , mapping reviews, and qualitative systematic reviews , just to name a few. The protocols and distinctions for review types are particularly delineated in health research fields, but we are seeing conventions quickly establishing themselves in other academic fields.

The below definitions are quoted from the very helpful book, Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review . London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

For more definitions, try:

- Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Sage Research Methods Online. A database devoted to research methodology. Includes handbooks, encyclopedia entries, and a research concepts map.

- Research Methods

- Report Writing

- Research--Methodology

- Research--Methodology--Handbooks, manuals, etc.

Note: There is unfortunately no subject heading specifically for "literature reviews" which brings together all related material.

Mapping Review : "A rapid search of the literature aiming to give a broad overview of the characteristics of a topic area. Mapping of existing research, identification of gaps, and a summary assessment of the quantity and quality of the available evidence helps to decide future areas for research or for systematic reviews." (Booth, Papaioannou & Sutton, 2012, p. 264)

Mixed Method Review : "A literature review that seeks to bring together data from quantitative and qualitative studies integrating them in a way that facilitates subsequent analysis" (Booth et al., p. 265).

Meta-analysis : "The process of combining statistically quantitative studies that have measured the same effect using similar methods and a common outcome measure" (Booth et al., p. 264).

Narrative Review: "A term used to describe a conventional overview of the literature, particularly when contrasted with a systematic review" (Booth et al., p. 265).

Note: this term is often used pejoratively, describing a review that is inadvertently guided by a confirmation bias.

Qualitative Evidence Synthesis : "An umbrella term increasingly used to describe a group of review types that attempt to synthesize and analyze findings from primary qualitative research studies" (Booth et al., p. 267).

Rapid Review : "Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p.96).

Note: Rapid reviews are often done when there are insufficient time and/or resources to conduct a systematic review. As stated by Butler et. al, "They aim to be rigorous and explicit in method and thus systematic but make concessions to the breadth or depth of the process by limiting particular aspects of the systematic review process" (as cited in Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 100).

Scoping Review: "A type of review that has as its primary objective the identification of the size and quality of research in a topic area in order to inform subsequent review" (Booth et al., p. 269).

Systematic Review : "A review of a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant research and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review" (Booth et al., p. 271).

Note : a systematic review (SR) is the most extensive and well-documented type of lit review, as well as potentially the most time-consuming. The idea with SRs is that the search process becomes a replicable scientific study in itself. This level of review will possibly not be necessary (or desirable) for your research project.

Many lit review types are based on organization-driven specific protocols for conducting the reviews. These protocols provide specific frameworks, checklists, and other guidance to the generic literature review sub-types. Here are a few popular examples:

Cochrane Review - known as the "gold standard" of systematic reviews, designed by the Cochrane Collaboration. Primarily used in health research literature reviews.

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . "The official document that describes in detail the process of preparing and maintaining Cochrane systematic reviews".

Campbell Review - the sister organization of the Cochrane Institute which focuses on systematic reviews in the social sciences.

- So you want to write a Campbell Systematic review?

- Campbell Information Retrieval Guide. The details of effective information searching

Literature Reviews in Psychology

A recent article in the Annual Review of Psychology provides a very helpful guide to conducting literature reviews specifically in the field of Psychology.

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. (2019). Annual Review of Psychology, 70 (1), 747-770. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Rapid Reviews have become increasingly common due to their flexibility, as well as the lack of time and resources available to do a comprehensive systematic review. McMaster University's National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT) has created a Rapid Review Guidebook , which "details each step in the rapid review process, with notes on how to tailor the process given resource limitations."

Scoping Review

There is no strict protocol for a scoping review (unlike Campbell and Cochrane reviews). The following are some recommended guidelines for scoping reviews:

- Scoping Reviews from the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis

- Current best practices for the conduct of scoping reviews, from the EQUATOR Network

In addition to protocols which provide holistic guidance for conducting specific kinds of reviews, there are also a vast number of frameworks, checklists, and other tools available to help focus your review and ensure comprehensiveness. Some provide broader-level guidance; others are targeted to specific parts of your reviews such as data extraction or reporting out results.

- PICO or PICOC A framework for posing a researchable question (population, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, context/environment)

- PRISMA Minimum items to report upon in a systematic review, as well as its extensions , such as PRISMA-ScR (for scoping reviews)

- SALSA framework: frames the literature review into four parts: search (S), appraisal(AL), synthesis(S), analysis(A)

- STARLITE Minimum requirements for reporting out on literature reviews.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Checklists Includes a checklist for evaluating Systematic Reviews.

These are just a sampling of specific guides generated from the ever-growing literature review industry.

Much of the online discussion about the use of Google Scholar in literature reviews seems to focus more on values and ideals, rather than a technical assessment of the search engine's role. Here are some things to keep in mind.

- It's good practice to use both Google Scholar and subject-specific databases (example: PsycINFO) for conducting a lit review of any type. For most graduate-level literature reviews, it is usually recommended to use both.

- You should search Google Scholar through the library's website when off-campus. This way you can avoid being prompted for payment to access articles that the SFU Library already subscribes to.

- Search tips for Google and Google Scholar

Google Advantages:

- Allows you to cast a wide net in your search.

- The most popular articles are revealed

- A high volume of articles are retrieved

- Google's algorithm helps compensate for poorly designed searches

- Full-text indexing of articles is now being done in Google Scholar

- A search feature allow you to search within articles citing your key article

- Excellent for known-item searching or locating a quote/citation

- Helpful when searching for very unique terminology (e.g., places and people)

- Times cited tool can help identify relevant articles

- Extensive searching of non-article, but academic, information items: universities' institutional repositories, US case law, grey literature , academic websites, etc.

Disadvantages:

- The database is not mapped to a specific discipline

- Much less search sophistication and manipulation supported

- Psuedo-Boolean operators

- Missing deep data (e.g., statistics)

- Mysterious algorithms and unknown source coverage at odds with the systematic and transparent requirement of a literature review.

- Searches are optimized (for example, by your location), thwarting the replicability criteria of most literature review types

- Low level of subject and author collocation - that is, bringing together all works by one author or one sub-topic

- Challenging to run searches that involve common words. A search for "art AND time", for example, might bring up results on the art of time management when you are looking for the representation of time in art. In contrast, searching by topic is readily facilitated by use of subject headings in discipline-specific databases. Google Scholar has no subject headings.

- New articles might not be pushed up if the popularity of an article is prioritized

- Indexes articles from predatory publishers , which may be hard to identify if working outside of your field

Unlike Google Scholar, subject specific databases such as PsycINFO , Medline , or Criminal Justice Abstracts are mapped to a disciplinary perspective. Article citations contain high-quality and detailed metadata. Metadata can be used to build specific searches and apply search limits relevant to your subject area. These databases also often offer access to specialized material in your area such as grey literature , psychological tests, statistics, books and dissertations.

For most graduate-level literature reviews, it is usually recommended to use both. Build careful searches in the subject/academic databases, and check Google Scholar as well.

For most graduate-level lit reviews, you will want to make use of the subject headings (aka descriptors) found in the various databases.

Subject headings are words or phrases assigned to articles, books, and other info items that describe the subject of their content. They are designed to succinctly capture a document's concepts, allowing the researcher to retrieve all articles/info items about that concept using one term. By identifying the subject headings associated with your research areas, and subsequently searching the database for other articles and materials assigned with that same subject heading, you are taking a significant measure to ensure the comprehensiveness of your literature review.

About subject headings:

- They are applied systematically : articles and books will usually have about 3-8 subject headings assigned to their bibliographic record.

- The subject headings come from a finite pool of terms - one that is updated frequently.

- They are often organized in a hierarchical taxonomy , with subject headings belonging to broader headings, and/or having narrower headings beneath them. Sometimes there are related terms (lateral) as well.

- They provide a standardized way to describe a concept. For instance, a subject heading of "physician" may be used to capture many of the natural language words that describe a physician such as doctor, family doctor, GP, and MD.

One way to identify subject headings (SHs) of interest to you is to start with a keyword search in a database, and see which SHs are associated with the articles of interest.

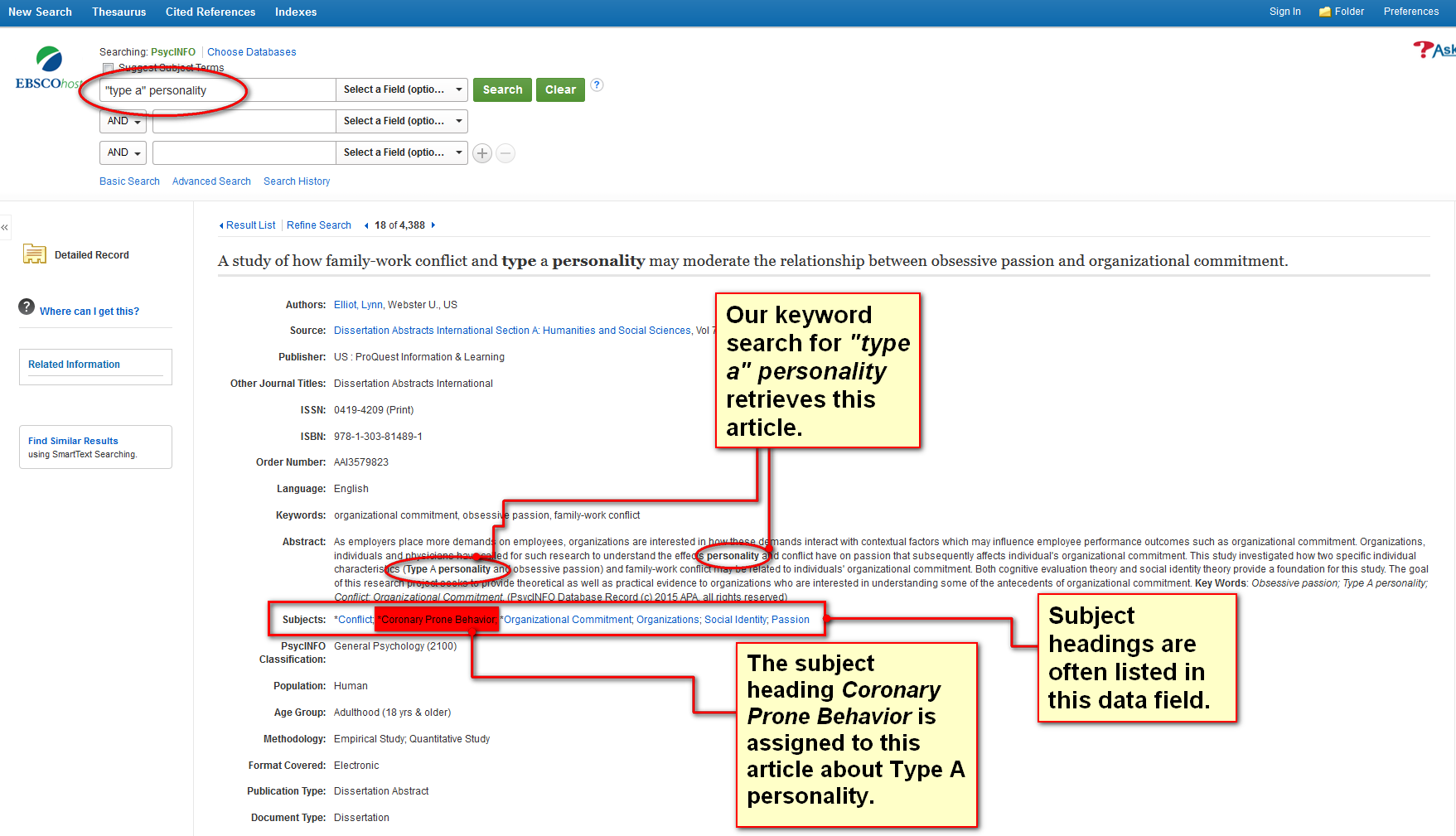

A. In the below example, we start with a keyword search for "type a" personality in PsycINFO . A more contemporary term to describe this phenomena is then found in the subject heading field:

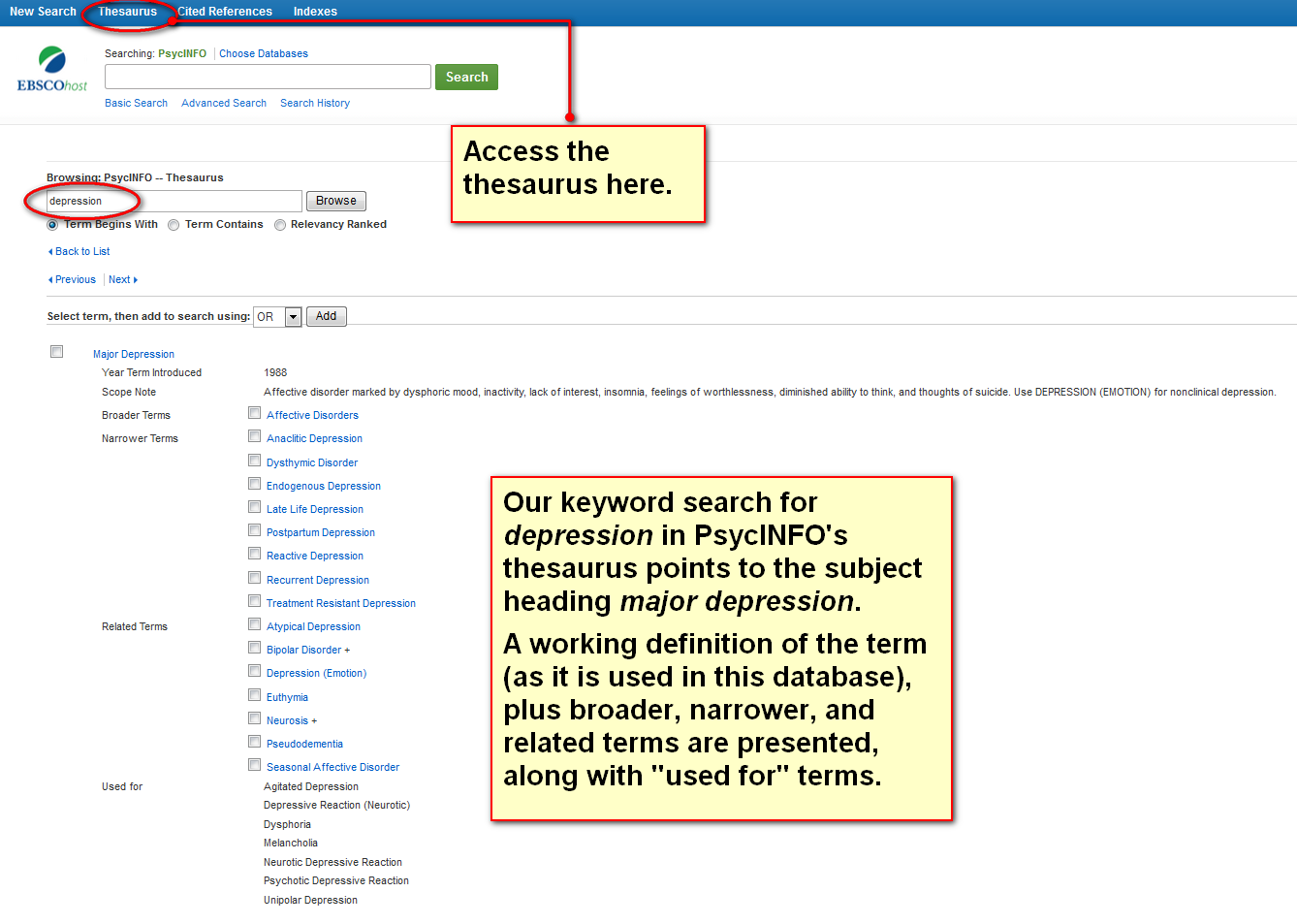

B. Another way to identify subject headings related to your topic is to go directly to a database's thesaurus or index. For example, if we are researching depression, the PsycINFO entry for major depression suggests some narrower terms we could focus our search by.

For more in-depth help with using subject headings in a literature review, please contact the Liaison Librarian in your subject area .

- NEW! Covidence . Covidence is a web-based literature review tool that will help you through the process of screening your references, data extraction, and keeping track of your work. Ideal for streamlining systematic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses, and other related methods of evidence synthesis.

- NVivo is a robust software package that helps with management and analysis of qualitative information.The Library's Research Commons offers extensive support for NVivo.

- Research Support Software offered by the Research Commons

Citation management software such as Zotero, Mendeley, or Endnote is essential for completing a substantial lit review. Citation software is a centralized, online location for managing your sources. Specifically, it allows you to:

- Access and manage your sources online, all in one place

- Import references from library databases and websites

- Automatically generate bibliographies and in-text citations within Microsoft Word

- Share your collection of sources with others, and work collaboratively with references

- De-duplicate your search results* (*Note: Mendeley is not recommended for deduplication in systematic reviews.)

- Annotate your citations. Some software allows you to mark up PDFs.

- Note trends in your research such as which journals or authors you cite from the most.

More information on Citation Management Software

Did you know that many databases allow you to save your search strategies? The advantages of saving and tracking your search strategies online in a literature review include:

- Developing your search strategy in a methodological manner, section by section. For instance, you can run searches for all synonyms and subjects headings associated with one concept, then combine them with different concepts in various combinations.

- Re-running your well-executed search in the future

- Creating search alerts based on a well-designed search, allowing you to stay notified of new research in your area

- Tracking and remember all of the searches you have done. Avoid inadvertently re-doing your searches by being well-documented and systematic as you go along - it's worth the extra effort!

Databases housed on the EBSCO plaform (examples: Business Source Complete, PsycINFO, Medline, Academic Search Premier) allow you to create an free account where you might save your searches:

- Using the EBSCOhost Search History - Tutorial [2:08]

- Creating a Search Alert in EBSCOhost - Tutorial [1:26]

How to Conduct a Literature Review: A Guide for Graduate Students

- Let's Get Started!

- Traditional or Narrative Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Typology of Reviews

- Literature Review Resources

- Developing a Search Strategy

- What Literature to Search

- Where to Search: Indexes and Databases

- Finding articles: Libkey Nomad

- Finding Dissertations and Theses

- Extending Your Searching with Citation Chains

- Forward Citation Chains - Cited Reference Searching

- Keeping up with the Literature

- Managing Your References

- Need More Information?

Bookmark This Guide!

https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/gradlitrev

Where to Get Help

Librarians at ISU are subject experts who can help with your research and course needs. There are experts available for every discipline at ISU who are ready to assist you with your information needs!

What we do:

- Answer questions via phone, chat and in-person

- Consult with student and faculty researchers on request

- Purchase materials for the collection

- Teach instruction session for ISU courses

- Support faculty getting ready for promotion & tenure reviews

- Help with data management plans

Find Your Librarian

“Google can bring you back 100,000 answers. A librarian can bring you back the right one.” - Neil Gaiman

The literature review is an important part of your thesis or dissertation. It is a survey of existing literature that provides context for your research contribution, and demonstrates your subject knowledge. It is also the way to tell the story of how your research extends knowledge in your field.

The first step to writing a successful literature review is knowing how to find and evaluate literature in your field. This guide is designed to introduce you to tools and give you skills you can use to effectively find the resources needed for your literature review.

Before getting started, familiarize yourself with some essential resources provided by the Graduate College:

- Dissertation and Thesis Information

- Center for Communication Excellence

- Graduate College Handbook

Below are some questions that you can discuss with your advisor as you begin your research:

Questions to ask as you think about your literature review:

What is my research question.

Choosing a valid research question is something you will need to discuss with your academic advisor and/or POS committee. Ideas for your topic may come from your coursework, lab rotations, or work as a research assistant. Having a specific research topic allows you to focus your research on a project that is manageable. Beginning work on your literature review can help narrow your topic.

What kind of literature review is appropriate for my research question?

Depending on your area of research, the type of literature review you do for your thesis will vary. Consult with your advisor about the requirements for your discipline. You can view theses and dissertations from your field in the library's Digital Repository can give you ideas about how your literature review should be structured.

What kind of literature should I use?

The kind of literature you use for your thesis will depend on your discipline. The Library has developed a list of Guides by Subject with discipline-specific resources. For a given subject area, look for the guide titles "[Discipline] Research Guide." You may also consult our liaison librarians for information about the literature available your research area.

How will I make sure that I find all the appropriate information that informs my research?

Consulting multiple sources of information is the best way to insure that you have done a comprehensive search of the literature in your area. The What Literature to Search tab has information about the types of resources you may need to search. You may also consult our liaison librarians for assistance with identifying resources..

How will I evaluate the literature to include trustworthy information and eliminate unnecessary or untrustworthy information?

While you are searching for relevant information about your topic you will need to think about the accuracy of the information, whether the information is from a reputable source, whether it is objective and current. Our guides about Evaluating Scholarly Books and Articles and Evaluating Websites will give you criteria to use when evaluating resources.

How should I organize my literature? What citation management program is best for me?

Citation management software can help you organize your references in folders and/or with tags. You can also annotate and highlight the PDFs within the software and usually the notes are searchable. To choose a good citation management software, you need to consider which one can be streamlined with your literature search and writing process. Here is a guide page comparing EndNote, Mendeley & Zotero. The Library also has guides for three of the major citation management tools:

- EndNote & EndNote Web Guide

- Mendeley Guide

- Getting Started with Zotero

What steps should I take to ensure academic integrity?

The best way to ensure academic integrity is to familiarize yourself with different types of intentional and unintentional plagiarism and learn about the University's standards for academic integrity. Start with this guide . The Library also has a guide about your rights and responsibilities regarding copyrighted images and figures that you include in your thesis.

Where can I find writing and editing help?

Writing and editing help is available at the Graduate College's Center for Communication Excellence . The CCE offers individual consultations, peer writing groups, workshops and seminars to help you improve your writing.

Where can I find I find formatting standards? Technical support?

The Graduate College has a Dissertation/ Thesis website with extensive examples and videos about formatting theses and dissertations. The site also has templates and formatting instructions for Word and LaTex .

What citation style should I use?

The Graduate College thesis guidelines require that you "use a consistent, current academic style for your discipline." The Library has a Citation Style Guides resource you can use for guidance on specific citation styles. If you are not sure, please consult your advisor or liaison librarians for help.

Adapted from The Literature Review: For Dissertations, by the University of Michigan Library. Available: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/dissertationlitreview

Center for Communication Excellence/ Library Workshop Slides

Slides from the CCE/ Library Workshop "A Citation Here...A Citation There...Pretty Soon You'll Have a Lit Review" held on February 21, 2024 are below:

- CCE Workshop February 21, 2024

- Next: Types of Literature Reviews >>

The library's collections and services are available to all ISU students, faculty, and staff and Parks Library is open to the public .

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/gradlitrev

How to Write a Literature Review

- Writing a Review of Literature Superb introduction from the University of Wisconsin at Madison

- Outline for Comprehensive Science Literature Reviews Written by a librarian, so the focus is on efficient searching. From Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship . For further details, see the full document .

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students From North Carolina State University Libraries

- Tips on Conducting the Literature Review From the Health Sciences Writing Centre at the University of Toronto

- Literature Review Demystified From the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library. Overview of the literature review including its purpose, research strategies, help for keeping track of your work, examples of published lit reviews, and books on graduate-level (and beyond) writing.

- Applying for Graduate School

- Understanding Expectations

- Developing Genre Awareness

- Establishing a Project’s Value

- Writing Scholarship and Research Proposals

Writing Literature Reviews

- Strategies for Writing About Literature

- Writing Theses and Dissertations

- Understanding the Publication Cycle

- Understanding Authorship

- Writing About Data

- Explaining Research to Diverse Audiences

- Writing with Integrity

- Revising with Intent

- Staying Motivated and Productive

- Creating a Writing Toolkit

- Building Grammatical Confidence

Graduate Writing: Writing Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are commonly written in graduate school, either as a standalone document or as part of a larger text (e.g., scholarship proposal, research project, thesis, dissertation), and provide an overview about what is currently known and not known about a particular research area. Literature refers primarily to the work of other scholars, captured in academic journal articles or monographs, though may include other documents too, such as government reports, white papers, and more.

Most graduate-level literature reviews are likely to be narrative reviews, but some students, especially those in health sciences , may be expected to produce a systematic review or a scoping (or mapping) review. Other literature reviews include critical reviews*, conceptual reviews, empirical reviews, meta-analysis reviews , and rapid reviews, among others.

* Critical review in different contexts may refer to an article or book critique.

While some graduate students will already be comfortable undertaking a narrative review, it is recommended that they work closely with their subject librarian when conducting any type of review for the first time. You can make an appointment with your subject librarian to learn more about how to navigate databases effectively, source grey literature, and more. Keep in mind that certain types of reviews may require academics to follow standardized procedures, both in terms of how research is undertaken and how it is written (e.g., PRISMA for scoping reviews ). Unsure of which review is right for you? Consider completing a questionnaire or reviewing resources to help make the decision-making process a bit easier.

Narrative literature reviews have several purposes. In conducting the review, the writer deepens their understanding of the present research (the literature) and, in doing so, clarifies their own research question or problem statement. A standalone literature review (sometimes referred to as a review article ) can also provide other scholars and professionals a useful overview of current research so that they can stay up to date in their field. However, one of the main purposes of the review is to provide justification for a research project by situating the project in relation to the work of other scholars.

While a narrative literature review should provide a sense of the breadth and depth of what the author has read, it is not necessary to include every single article or book that is tangentially related to the topic at hand. Instead, the text should serve the reader so that they have sufficient context to understand the issue(s) being explored.

Situating Research: Create a Research Space (CARS)

For literature reviews that are integrated into the paper’s introduction, the Create a Research Space (CARS) model , as articulated by John Swales, can be an effective method for helping to justify one’s own project. It involves the following three rhetorical moves that help establish an argument for one’s work by explaining

- what is already known about a topic (what has already been found)

- what is not known about a topic (the gap in the literature)

- what will be/is known about a topic because of one’s project (entering the gap)

This structure is frequently used within academia, echoing a problem-solution structure that establishes an appealing rhetorical situation readers can easily understand.

While CARS provides a broad structure for organizing a narrative literature review, within the “known” section additional thought must be given to overall organization. In general, there are three main options: chronological, thematic, or methodological . Within a chronological structure, the writer follows how the topic has developed over time; within a thematic structure, the writer identifies and develops themes (and sub-themes) around which the research circles; and within a methodological structure, the writer groups studies according to how they were designed (e.g., qualitative vs. quantitative studies). In practice, many writers blend aspects of two of more of these structures when writing their reviews.

Looking to fine-tune your literature review? Select a comparable review from your field and examine how it has been structured. Ask yourself how the authors have organized the text. Do they follow CARS moves?

Looking for more information on writing literature reviews?

- Hastings, C. (2016, September 27). Get lit: The literature review [Video]. YouTube . https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9la5ytz9MmM

- Hillary, A. (2017, December 13). I found a gap in the lit, now what? Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/gradhacker/i-found-gap-lit-now-what

- Costanza-Robinson, M., Maxwell, A., Wright, C., & Bertollini, M.E. (2021). Gap statements . Write Like a Scientist. https://sites.middlebury.edu/middsciwriting/overview/organization/gap-statements/

- Cornell University Library (2022, April 7). What is Evidence Synthesis? A Guide to Evidence Synthesis. https://guides.library.cornell.edu/evidence-synthesis/types

- Guerin, C. (2013, September 1). Literature reviews – trust yourself! DoctoralWriting SIG. https://doctoralwriting.wordpress.com/2013/09/01/literature-reviews-trust-yourself/

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104 , 333 – 339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Tay, A. (2020, December 4). How to write a superb literature review. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

- Willyard, C. (2012, March). Literature reviews made easy. gradPSYCH, 10 (2). https://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2012/03/literature

Keeping the Literature Organized

One of the more challenging aspects of crafting literature reviews is managing the volume of sources that you are expected to read, interrogate, and integrate into the final text.

Citation managers , spreadsheets and annotated bibliographies are all methods by which students can keep track of their sources.

Having a system in place from the start means that it is easier to synthesize and cite the research during the drafting and revising of the review.

Looking for more information on how to keep literature organized?

- Clarke, K. (2017, October 24). Organizing your literature: Spreadsheet style . Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/gradhacker/organizing-your-literature-spreadsheet-style

- Perkel, J. (2020). Streamline your writing — and collaborations — with these reference managers. Nature, 585 , 149 – 150. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02491-2

Synthesis and the Literature Review

Synthesis is a central characteristic of literature reviews, demonstrating a writer’s ability to group sources together based on shared information. Synthesis also creates more readable text by reducing needless repetition.

Consider the examples below. Which do you prefer reading?

Example 1: Baptiste (2001) reviewed 85 instances of elderly women who experienced hip fractures following falls. He determined that in most cases, these falls were preventable. Beyond the physiological impact of these falls, the costs associated with such injuries were significant. Adams (2011) also studied instances of elderly women experiencing hip fractures in her study. According to her research, most of these falls were preventable. In 2018, Statistics Canada released a report on the costs associated with bone fractures in elderly populations, which often result in expensive hospitalizations. These injuries are often caused by falls and are largely preventable.

Example 2: The costs associated with bone fractures among elderly populations are notable as these injuries often result in expensive hospitalizations (Baptiste, 2001; Statistics Canada, 2018). However, some of these injuries may be avoidable. For instance, two studies studying hip fractures experienced by elderly women who had fallen found that most falls were preventable (Baptiste, 2001; Adams, 2011).

Did you prefer the second example? Most readers do as it communicates the same information as the first but in a more concise way. That is the power of synthesis.

Synthesis can also be understood as a form of pattern recognition that involves writers asking themselves how different sources relate to each other. Because of this focus on relationships, the following questions can also be used to generate synthesis:

- Are researchers asking similar or different questions about the same topic?

- Do the scholars agree? Or do they contradict each other?

- What debate(s) are emerging?

- Do researchers interpret data in similar or different ways?

- What methodologies have been used to investigate comparable questions?

- How are scholars responding to previous research?

- How does the research fit into the current academic conversation?

Graduate students may also wish to use a synthesis matrix . These are useful tools that can be easily tailored to any research project and make visualizing commonalities among studies as simple as glancing at a table.

Looking for more information on how to synthesize effectively?

- Frederiksen, L., & Phelps, S. F. (n.d.). Synthesizing Sources. In Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students . Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/literaturereviewsedunursing/chapter/chapter-7-synthesizing-sources/

- McNeill, J. (2020, March 10). Step-by-step synthesis. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/gradhacker/step-step-synthesis

- << Previous: Writing Scholarship and Research Proposals

- Next: Strategies for Writing About Literature >>

- Library A to Z

- Follow on Facebook

- Follow on Twitter

- Follow on YouTube

- Follow on Instagram

The University of Saskatchewan's main campus is situated on Treaty 6 Territory and the Homeland of the Métis.

© University of Saskatchewan Disclaimer | Privacy

- Last Updated: Oct 29, 2024 9:46 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usask.ca/grad_writing

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say "literature review" or refer to "the literature," we are talking about the research (scholarship) in a given field. You will often see the terms "the research," "the ...

A literature review is a common genre for many types of writing you'll have to do as a graduate student and scholar. Not only do dissertations contain literature reviews, but most articles and grant proposals have some form of literature review included in them.

usually be some element of literature review in the introduction. And if you have to write a grant application, you will be expected to review the work that has already been done in your area. However, just because we all have to do this a lot, doesn't make the task any easier, and indeed for many, writing a literature review is one of