Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Journal article analysis assignments require you to summarize and critically assess the quality of an empirical research study published in a scholarly [a.k.a., academic, peer-reviewed] journal. The article may be assigned by the professor, chosen from course readings listed in the syllabus, or you must locate an article on your own, usually with the requirement that you search using a reputable library database, such as, JSTOR or ProQuest . The article chosen is expected to relate to the overall discipline of the course, specific course content, or key concepts discussed in class. In some cases, the purpose of the assignment is to analyze an article that is part of the literature review for a future research project.

Analysis of an article can be assigned to students individually or as part of a small group project. The final product is usually in the form of a short paper [typically 1- 6 double-spaced pages] that addresses key questions the professor uses to guide your analysis or that assesses specific parts of a scholarly research study [e.g., the research problem, methodology, discussion, conclusions or findings]. The analysis paper may be shared on a digital course management platform and/or presented to the class for the purpose of promoting a wider discussion about the topic of the study. Although assigned in any level of undergraduate and graduate coursework in the social and behavioral sciences, professors frequently include this assignment in upper division courses to help students learn how to effectively identify, read, and analyze empirical research within their major.

Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Benefits of Journal Article Analysis Assignments

Analyzing and synthesizing a scholarly journal article is intended to help students obtain the reading and critical thinking skills needed to develop and write their own research papers. This assignment also supports workplace skills where you could be asked to summarize a report or other type of document and report it, for example, during a staff meeting or for a presentation.

There are two broadly defined ways that analyzing a scholarly journal article supports student learning:

Improve Reading Skills

Conducting research requires an ability to review, evaluate, and synthesize prior research studies. Reading prior research requires an understanding of the academic writing style , the type of epistemological beliefs or practices underpinning the research design, and the specific vocabulary and technical terminology [i.e., jargon] used within a discipline. Reading scholarly articles is important because academic writing is unfamiliar to most students; they have had limited exposure to using peer-reviewed journal articles prior to entering college or students have yet to gain exposure to the specific academic writing style of their disciplinary major. Learning how to read scholarly articles also requires careful and deliberate concentration on how authors use specific language and phrasing to convey their research, the problem it addresses, its relationship to prior research, its significance, its limitations, and how authors connect methods of data gathering to the results so as to develop recommended solutions derived from the overall research process.

Improve Comprehension Skills

In addition to knowing how to read scholarly journals articles, students must learn how to effectively interpret what the scholar(s) are trying to convey. Academic writing can be dense, multi-layered, and non-linear in how information is presented. In addition, scholarly articles contain footnotes or endnotes, references to sources, multiple appendices, and, in some cases, non-textual elements [e.g., graphs, charts] that can break-up the reader’s experience with the narrative flow of the study. Analyzing articles helps students practice comprehending these elements of writing, critiquing the arguments being made, reflecting upon the significance of the research, and how it relates to building new knowledge and understanding or applying new approaches to practice. Comprehending scholarly writing also involves thinking critically about where you fit within the overall dialogue among scholars concerning the research problem, finding possible gaps in the research that require further analysis, or identifying where the author(s) has failed to examine fully any specific elements of the study.

In addition, journal article analysis assignments are used by professors to strengthen discipline-specific information literacy skills, either alone or in relation to other tasks, such as, giving a class presentation or participating in a group project. These benefits can include the ability to:

- Effectively paraphrase text, which leads to a more thorough understanding of the overall study;

- Identify and describe strengths and weaknesses of the study and their implications;

- Relate the article to other course readings and in relation to particular research concepts or ideas discussed during class;

- Think critically about the research and summarize complex ideas contained within;

- Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

- Model the type of source summary and critique you should do for any college-level research paper; and,

- Increase interest and engagement with the research problem of the study as well as with the discipline.

Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students make the most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946.

Structure and Organization

A journal article analysis paper should be written in paragraph format and include an instruction to the study, your analysis of the research, and a conclusion that provides an overall assessment of the author's work, along with an explanation of what you believe is the study's overall impact and significance. Unless the purpose of the assignment is to examine foundational studies published many years ago, you should select articles that have been published relatively recently [e.g., within the past few years].

Since the research has been completed, reference to the study in your paper should be written in the past tense, with your analysis stated in the present tense [e.g., “The author portrayed access to health care services in rural areas as primarily a problem of having reliable transportation. However, I believe the author is overgeneralizing this issue because...”].

Introduction Section

The first section of a journal analysis paper should describe the topic of the article and highlight the author’s main points. This includes describing the research problem and theoretical framework, the rationale for the research, the methods of data gathering and analysis, the key findings, and the author’s final conclusions and recommendations. The narrative should focus on the act of describing rather than analyzing. Think of the introduction as a more comprehensive and detailed descriptive abstract of the study.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the introduction section may include:

- Who are the authors and what credentials do they hold that contributes to the validity of the study?

- What was the research problem being investigated?

- What type of research design was used to investigate the research problem?

- What theoretical idea(s) and/or research questions were used to address the problem?

- What was the source of the data or information used as evidence for analysis?

- What methods were applied to investigate this evidence?

- What were the author's overall conclusions and key findings?

Critical Analysis Section

The second section of a journal analysis paper should describe the strengths and weaknesses of the study and analyze its significance and impact. This section is where you shift the narrative from describing to analyzing. Think critically about the research in relation to other course readings, what has been discussed in class, or based on your own life experiences. If you are struggling to identify any weaknesses, explain why you believe this to be true. However, no study is perfect, regardless of how laudable its design may be. Given this, think about the repercussions of the choices made by the author(s) and how you might have conducted the study differently. Examples can include contemplating the choice of what sources were included or excluded in support of examining the research problem, the choice of the method used to analyze the data, or the choice to highlight specific recommended courses of action and/or implications for practice over others. Another strategy is to place yourself within the research study itself by thinking reflectively about what may be missing if you had been a participant in the study or if the recommended courses of action specifically targeted you or your community.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the analysis section may include:

Introduction

- Did the author clearly state the problem being investigated?

- What was your reaction to and perspective on the research problem?

- Was the study’s objective clearly stated? Did the author clearly explain why the study was necessary?

- How well did the introduction frame the scope of the study?

- Did the introduction conclude with a clear purpose statement?

Literature Review

- Did the literature review lay a foundation for understanding the significance of the research problem?

- Did the literature review provide enough background information to understand the problem in relation to relevant contexts [e.g., historical, economic, social, cultural, etc.].

- Did literature review effectively place the study within the domain of prior research? Is anything missing?

- Was the literature review organized by conceptual categories or did the author simply list and describe sources?

- Did the author accurately explain how the data or information were collected?

- Was the data used sufficient in supporting the study of the research problem?

- Was there another methodological approach that could have been more illuminating?

- Give your overall evaluation of the methods used in this article. How much trust would you put in generating relevant findings?

Results and Discussion

- Were the results clearly presented?

- Did you feel that the results support the theoretical and interpretive claims of the author? Why?

- What did the author(s) do especially well in describing or analyzing their results?

- Was the author's evaluation of the findings clearly stated?

- How well did the discussion of the results relate to what is already known about the research problem?

- Was the discussion of the results free of repetition and redundancies?

- What interpretations did the authors make that you think are in incomplete, unwarranted, or overstated?

- Did the conclusion effectively capture the main points of study?

- Did the conclusion address the research questions posed? Do they seem reasonable?

- Were the author’s conclusions consistent with the evidence and arguments presented?

- Has the author explained how the research added new knowledge or understanding?

Overall Writing Style

- If the article included tables, figures, or other non-textual elements, did they contribute to understanding the study?

- Were ideas developed and related in a logical sequence?

- Were transitions between sections of the article smooth and easy to follow?

Overall Evaluation Section

The final section of a journal analysis paper should bring your thoughts together into a coherent assessment of the value of the research study . This section is where the narrative flow transitions from analyzing specific elements of the article to critically evaluating the overall study. Explain what you view as the significance of the research in relation to the overall course content and any relevant discussions that occurred during class. Think about how the article contributes to understanding the overall research problem, how it fits within existing literature on the topic, how it relates to the course, and what it means to you as a student researcher. In some cases, your professor will also ask you to describe your experiences writing the journal article analysis paper as part of a reflective learning exercise.

Possible questions to help guide your writing of the conclusion and evaluation section may include:

- Was the structure of the article clear and well organized?

- Was the topic of current or enduring interest to you?

- What were the main weaknesses of the article? [this does not refer to limitations stated by the author, but what you believe are potential flaws]

- Was any of the information in the article unclear or ambiguous?

- What did you learn from the research? If nothing stood out to you, explain why.

- Assess the originality of the research. Did you believe it contributed new understanding of the research problem?

- Were you persuaded by the author’s arguments?

- If the author made any final recommendations, will they be impactful if applied to practice?

- In what ways could future research build off of this study?

- What implications does the study have for daily life?

- Was the use of non-textual elements, footnotes or endnotes, and/or appendices helpful in understanding the research?

- What lingering questions do you have after analyzing the article?

NOTE: Avoid using quotes. One of the main purposes of writing an article analysis paper is to learn how to effectively paraphrase and use your own words to summarize a scholarly research study and to explain what the research means to you. Using and citing a direct quote from the article should only be done to help emphasize a key point or to underscore an important concept or idea.

Business: The Article Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing, Grand Valley State University; Bachiochi, Peter et al. "Using Empirical Article Analysis to Assess Research Methods Courses." Teaching of Psychology 38 (2011): 5-9; Brosowsky, Nicholaus P. et al. “Teaching Undergraduate Students to Read Empirical Articles: An Evaluation and Revision of the QALMRI Method.” PsyArXi Preprints , 2020; Holster, Kristin. “Article Evaluation Assignment”. TRAILS: Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology . Washington DC: American Sociological Association, 2016; Kershaw, Trina C., Jennifer Fugate, and Aminda J. O'Hare. "Teaching Undergraduates to Understand Published Research through Structured Practice in Identifying Key Research Concepts." Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology . Advance online publication, 2020; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Reviewer's Guide . SAGE Reviewer Gateway, SAGE Journals; Sego, Sandra A. and Anne E. Stuart. "Learning to Read Empirical Articles in General Psychology." Teaching of Psychology 43 (2016): 38-42; Kershaw, Trina C., Jordan P. Lippman, and Jennifer Fugate. "Practice Makes Proficient: Teaching Undergraduate Students to Understand Published Research." Instructional Science 46 (2018): 921-946; Gyuris, Emma, and Laura Castell. "To Tell Them or Show Them? How to Improve Science Students’ Skills of Critical Reading." International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 21 (2013): 70-80; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36; MacMillan, Margy and Allison MacKenzie. "Strategies for Integrating Information Literacy and Academic Literacy: Helping Undergraduate Students Make the Most of Scholarly Articles." Library Management 33 (2012): 525-535.

Writing Tip

Not All Scholarly Journal Articles Can Be Critically Analyzed

There are a variety of articles published in scholarly journals that do not fit within the guidelines of an article analysis assignment. This is because the work cannot be empirically examined or it does not generate new knowledge in a way which can be critically analyzed.

If you are required to locate a research study on your own, avoid selecting these types of journal articles:

- Theoretical essays which discuss concepts, assumptions, and propositions, but report no empirical research;

- Statistical or methodological papers that may analyze data, but the bulk of the work is devoted to refining a new measurement, statistical technique, or modeling procedure;

- Articles that review, analyze, critique, and synthesize prior research, but do not report any original research;

- Brief essays devoted to research methods and findings;

- Articles written by scholars in popular magazines or industry trade journals;

- Academic commentary that discusses research trends or emerging concepts and ideas, but does not contain citations to sources; and

- Pre-print articles that have been posted online, but may undergo further editing and revision by the journal's editorial staff before final publication. An indication that an article is a pre-print is that it has no volume, issue, or page numbers assigned to it.

Journal Analysis Assignment - Myers . Writing@CSU, Colorado State University; Franco, Josue. “Introducing the Analysis of Journal Articles.” Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association’s 2020 Teaching and Learning Conference, February 7-9, 2020, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Woodward-Kron, Robyn. "Critical Analysis and the Journal Article Review Assignment." Prospect 18 (August 2003): 20-36.

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Giving an Oral Presentation >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

The Beginner's Guide to Statistical Analysis | 5 Steps & Examples

Statistical analysis means investigating trends, patterns, and relationships using quantitative data . It is an important research tool used by scientists, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

To draw valid conclusions, statistical analysis requires careful planning from the very start of the research process . You need to specify your hypotheses and make decisions about your research design, sample size, and sampling procedure.

After collecting data from your sample, you can organize and summarize the data using descriptive statistics . Then, you can use inferential statistics to formally test hypotheses and make estimates about the population. Finally, you can interpret and generalize your findings.

This article is a practical introduction to statistical analysis for students and researchers. We’ll walk you through the steps using two research examples. The first investigates a potential cause-and-effect relationship, while the second investigates a potential correlation between variables.

Table of contents

Step 1: write your hypotheses and plan your research design, step 2: collect data from a sample, step 3: summarize your data with descriptive statistics, step 4: test hypotheses or make estimates with inferential statistics, step 5: interpret your results, other interesting articles.

To collect valid data for statistical analysis, you first need to specify your hypotheses and plan out your research design.

Writing statistical hypotheses

The goal of research is often to investigate a relationship between variables within a population . You start with a prediction, and use statistical analysis to test that prediction.

A statistical hypothesis is a formal way of writing a prediction about a population. Every research prediction is rephrased into null and alternative hypotheses that can be tested using sample data.

While the null hypothesis always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

- Null hypothesis: A 5-minute meditation exercise will have no effect on math test scores in teenagers.

- Alternative hypothesis: A 5-minute meditation exercise will improve math test scores in teenagers.

- Null hypothesis: Parental income and GPA have no relationship with each other in college students.

- Alternative hypothesis: Parental income and GPA are positively correlated in college students.

Planning your research design

A research design is your overall strategy for data collection and analysis. It determines the statistical tests you can use to test your hypothesis later on.

First, decide whether your research will use a descriptive, correlational, or experimental design. Experiments directly influence variables, whereas descriptive and correlational studies only measure variables.

- In an experimental design , you can assess a cause-and-effect relationship (e.g., the effect of meditation on test scores) using statistical tests of comparison or regression.

- In a correlational design , you can explore relationships between variables (e.g., parental income and GPA) without any assumption of causality using correlation coefficients and significance tests.

- In a descriptive design , you can study the characteristics of a population or phenomenon (e.g., the prevalence of anxiety in U.S. college students) using statistical tests to draw inferences from sample data.

Your research design also concerns whether you’ll compare participants at the group level or individual level, or both.

- In a between-subjects design , you compare the group-level outcomes of participants who have been exposed to different treatments (e.g., those who performed a meditation exercise vs those who didn’t).

- In a within-subjects design , you compare repeated measures from participants who have participated in all treatments of a study (e.g., scores from before and after performing a meditation exercise).

- In a mixed (factorial) design , one variable is altered between subjects and another is altered within subjects (e.g., pretest and posttest scores from participants who either did or didn’t do a meditation exercise).

- Experimental

- Correlational

First, you’ll take baseline test scores from participants. Then, your participants will undergo a 5-minute meditation exercise. Finally, you’ll record participants’ scores from a second math test.

In this experiment, the independent variable is the 5-minute meditation exercise, and the dependent variable is the math test score from before and after the intervention. Example: Correlational research design In a correlational study, you test whether there is a relationship between parental income and GPA in graduating college students. To collect your data, you will ask participants to fill in a survey and self-report their parents’ incomes and their own GPA.

Measuring variables

When planning a research design, you should operationalize your variables and decide exactly how you will measure them.

For statistical analysis, it’s important to consider the level of measurement of your variables, which tells you what kind of data they contain:

- Categorical data represents groupings. These may be nominal (e.g., gender) or ordinal (e.g. level of language ability).

- Quantitative data represents amounts. These may be on an interval scale (e.g. test score) or a ratio scale (e.g. age).

Many variables can be measured at different levels of precision. For example, age data can be quantitative (8 years old) or categorical (young). If a variable is coded numerically (e.g., level of agreement from 1–5), it doesn’t automatically mean that it’s quantitative instead of categorical.

Identifying the measurement level is important for choosing appropriate statistics and hypothesis tests. For example, you can calculate a mean score with quantitative data, but not with categorical data.

In a research study, along with measures of your variables of interest, you’ll often collect data on relevant participant characteristics.

| Variable | Type of data |

|---|---|

| Age | Quantitative (ratio) |

| Gender | Categorical (nominal) |

| Race or ethnicity | Categorical (nominal) |

| Baseline test scores | Quantitative (interval) |

| Final test scores | Quantitative (interval) |

| Parental income | Quantitative (ratio) |

|---|---|

| GPA | Quantitative (interval) |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In most cases, it’s too difficult or expensive to collect data from every member of the population you’re interested in studying. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

Statistical analysis allows you to apply your findings beyond your own sample as long as you use appropriate sampling procedures . You should aim for a sample that is representative of the population.

Sampling for statistical analysis

There are two main approaches to selecting a sample.

- Probability sampling: every member of the population has a chance of being selected for the study through random selection.

- Non-probability sampling: some members of the population are more likely than others to be selected for the study because of criteria such as convenience or voluntary self-selection.

In theory, for highly generalizable findings, you should use a probability sampling method. Random selection reduces several types of research bias , like sampling bias , and ensures that data from your sample is actually typical of the population. Parametric tests can be used to make strong statistical inferences when data are collected using probability sampling.

But in practice, it’s rarely possible to gather the ideal sample. While non-probability samples are more likely to at risk for biases like self-selection bias , they are much easier to recruit and collect data from. Non-parametric tests are more appropriate for non-probability samples, but they result in weaker inferences about the population.

If you want to use parametric tests for non-probability samples, you have to make the case that:

- your sample is representative of the population you’re generalizing your findings to.

- your sample lacks systematic bias.

Keep in mind that external validity means that you can only generalize your conclusions to others who share the characteristics of your sample. For instance, results from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic samples (e.g., college students in the US) aren’t automatically applicable to all non-WEIRD populations.

If you apply parametric tests to data from non-probability samples, be sure to elaborate on the limitations of how far your results can be generalized in your discussion section .

Create an appropriate sampling procedure

Based on the resources available for your research, decide on how you’ll recruit participants.

- Will you have resources to advertise your study widely, including outside of your university setting?

- Will you have the means to recruit a diverse sample that represents a broad population?

- Do you have time to contact and follow up with members of hard-to-reach groups?

Your participants are self-selected by their schools. Although you’re using a non-probability sample, you aim for a diverse and representative sample. Example: Sampling (correlational study) Your main population of interest is male college students in the US. Using social media advertising, you recruit senior-year male college students from a smaller subpopulation: seven universities in the Boston area.

Calculate sufficient sample size

Before recruiting participants, decide on your sample size either by looking at other studies in your field or using statistics. A sample that’s too small may be unrepresentative of the sample, while a sample that’s too large will be more costly than necessary.

There are many sample size calculators online. Different formulas are used depending on whether you have subgroups or how rigorous your study should be (e.g., in clinical research). As a rule of thumb, a minimum of 30 units or more per subgroup is necessary.

To use these calculators, you have to understand and input these key components:

- Significance level (alpha): the risk of rejecting a true null hypothesis that you are willing to take, usually set at 5%.

- Statistical power : the probability of your study detecting an effect of a certain size if there is one, usually 80% or higher.

- Expected effect size : a standardized indication of how large the expected result of your study will be, usually based on other similar studies.

- Population standard deviation: an estimate of the population parameter based on a previous study or a pilot study of your own.

Once you’ve collected all of your data, you can inspect them and calculate descriptive statistics that summarize them.

Inspect your data

There are various ways to inspect your data, including the following:

- Organizing data from each variable in frequency distribution tables .

- Displaying data from a key variable in a bar chart to view the distribution of responses.

- Visualizing the relationship between two variables using a scatter plot .

By visualizing your data in tables and graphs, you can assess whether your data follow a skewed or normal distribution and whether there are any outliers or missing data.

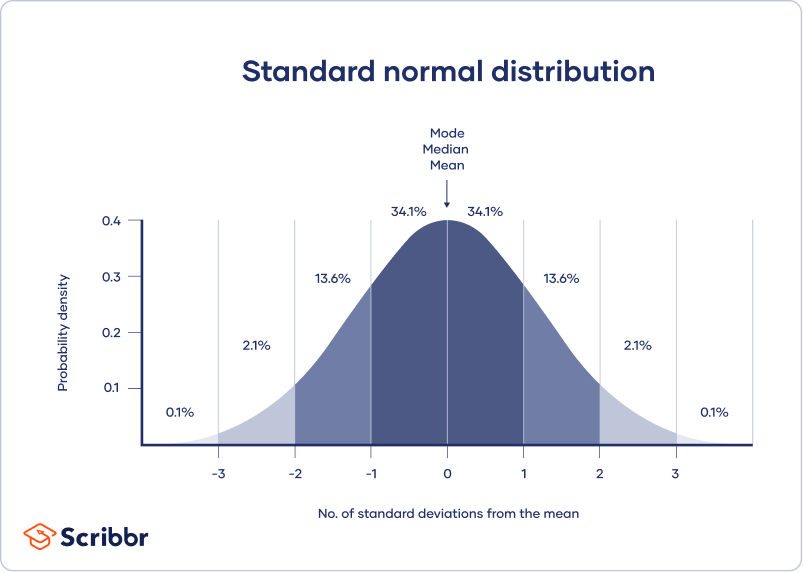

A normal distribution means that your data are symmetrically distributed around a center where most values lie, with the values tapering off at the tail ends.

In contrast, a skewed distribution is asymmetric and has more values on one end than the other. The shape of the distribution is important to keep in mind because only some descriptive statistics should be used with skewed distributions.

Extreme outliers can also produce misleading statistics, so you may need a systematic approach to dealing with these values.

Calculate measures of central tendency

Measures of central tendency describe where most of the values in a data set lie. Three main measures of central tendency are often reported:

- Mode : the most popular response or value in the data set.

- Median : the value in the exact middle of the data set when ordered from low to high.

- Mean : the sum of all values divided by the number of values.

However, depending on the shape of the distribution and level of measurement, only one or two of these measures may be appropriate. For example, many demographic characteristics can only be described using the mode or proportions, while a variable like reaction time may not have a mode at all.

Calculate measures of variability

Measures of variability tell you how spread out the values in a data set are. Four main measures of variability are often reported:

- Range : the highest value minus the lowest value of the data set.

- Interquartile range : the range of the middle half of the data set.

- Standard deviation : the average distance between each value in your data set and the mean.

- Variance : the square of the standard deviation.

Once again, the shape of the distribution and level of measurement should guide your choice of variability statistics. The interquartile range is the best measure for skewed distributions, while standard deviation and variance provide the best information for normal distributions.

Using your table, you should check whether the units of the descriptive statistics are comparable for pretest and posttest scores. For example, are the variance levels similar across the groups? Are there any extreme values? If there are, you may need to identify and remove extreme outliers in your data set or transform your data before performing a statistical test.

| Pretest scores | Posttest scores | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 68.44 | 75.25 |

| Standard deviation | 9.43 | 9.88 |

| Variance | 88.96 | 97.96 |

| Range | 36.25 | 45.12 |

| 30 | ||

From this table, we can see that the mean score increased after the meditation exercise, and the variances of the two scores are comparable. Next, we can perform a statistical test to find out if this improvement in test scores is statistically significant in the population. Example: Descriptive statistics (correlational study) After collecting data from 653 students, you tabulate descriptive statistics for annual parental income and GPA.

It’s important to check whether you have a broad range of data points. If you don’t, your data may be skewed towards some groups more than others (e.g., high academic achievers), and only limited inferences can be made about a relationship.

| Parental income (USD) | GPA | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 62,100 | 3.12 |

| Standard deviation | 15,000 | 0.45 |

| Variance | 225,000,000 | 0.16 |

| Range | 8,000–378,000 | 2.64–4.00 |

| 653 | ||

A number that describes a sample is called a statistic , while a number describing a population is called a parameter . Using inferential statistics , you can make conclusions about population parameters based on sample statistics.

Researchers often use two main methods (simultaneously) to make inferences in statistics.

- Estimation: calculating population parameters based on sample statistics.

- Hypothesis testing: a formal process for testing research predictions about the population using samples.

You can make two types of estimates of population parameters from sample statistics:

- A point estimate : a value that represents your best guess of the exact parameter.

- An interval estimate : a range of values that represent your best guess of where the parameter lies.

If your aim is to infer and report population characteristics from sample data, it’s best to use both point and interval estimates in your paper.

You can consider a sample statistic a point estimate for the population parameter when you have a representative sample (e.g., in a wide public opinion poll, the proportion of a sample that supports the current government is taken as the population proportion of government supporters).

There’s always error involved in estimation, so you should also provide a confidence interval as an interval estimate to show the variability around a point estimate.

A confidence interval uses the standard error and the z score from the standard normal distribution to convey where you’d generally expect to find the population parameter most of the time.

Hypothesis testing

Using data from a sample, you can test hypotheses about relationships between variables in the population. Hypothesis testing starts with the assumption that the null hypothesis is true in the population, and you use statistical tests to assess whether the null hypothesis can be rejected or not.

Statistical tests determine where your sample data would lie on an expected distribution of sample data if the null hypothesis were true. These tests give two main outputs:

- A test statistic tells you how much your data differs from the null hypothesis of the test.

- A p value tells you the likelihood of obtaining your results if the null hypothesis is actually true in the population.

Statistical tests come in three main varieties:

- Comparison tests assess group differences in outcomes.

- Regression tests assess cause-and-effect relationships between variables.

- Correlation tests assess relationships between variables without assuming causation.

Your choice of statistical test depends on your research questions, research design, sampling method, and data characteristics.

Parametric tests

Parametric tests make powerful inferences about the population based on sample data. But to use them, some assumptions must be met, and only some types of variables can be used. If your data violate these assumptions, you can perform appropriate data transformations or use alternative non-parametric tests instead.

A regression models the extent to which changes in a predictor variable results in changes in outcome variable(s).

- A simple linear regression includes one predictor variable and one outcome variable.

- A multiple linear regression includes two or more predictor variables and one outcome variable.

Comparison tests usually compare the means of groups. These may be the means of different groups within a sample (e.g., a treatment and control group), the means of one sample group taken at different times (e.g., pretest and posttest scores), or a sample mean and a population mean.

- A t test is for exactly 1 or 2 groups when the sample is small (30 or less).

- A z test is for exactly 1 or 2 groups when the sample is large.

- An ANOVA is for 3 or more groups.

The z and t tests have subtypes based on the number and types of samples and the hypotheses:

- If you have only one sample that you want to compare to a population mean, use a one-sample test .

- If you have paired measurements (within-subjects design), use a dependent (paired) samples test .

- If you have completely separate measurements from two unmatched groups (between-subjects design), use an independent (unpaired) samples test .

- If you expect a difference between groups in a specific direction, use a one-tailed test .

- If you don’t have any expectations for the direction of a difference between groups, use a two-tailed test .

The only parametric correlation test is Pearson’s r . The correlation coefficient ( r ) tells you the strength of a linear relationship between two quantitative variables.

However, to test whether the correlation in the sample is strong enough to be important in the population, you also need to perform a significance test of the correlation coefficient, usually a t test, to obtain a p value. This test uses your sample size to calculate how much the correlation coefficient differs from zero in the population.

You use a dependent-samples, one-tailed t test to assess whether the meditation exercise significantly improved math test scores. The test gives you:

- a t value (test statistic) of 3.00

- a p value of 0.0028

Although Pearson’s r is a test statistic, it doesn’t tell you anything about how significant the correlation is in the population. You also need to test whether this sample correlation coefficient is large enough to demonstrate a correlation in the population.

A t test can also determine how significantly a correlation coefficient differs from zero based on sample size. Since you expect a positive correlation between parental income and GPA, you use a one-sample, one-tailed t test. The t test gives you:

- a t value of 3.08

- a p value of 0.001

The final step of statistical analysis is interpreting your results.

Statistical significance

In hypothesis testing, statistical significance is the main criterion for forming conclusions. You compare your p value to a set significance level (usually 0.05) to decide whether your results are statistically significant or non-significant.

Statistically significant results are considered unlikely to have arisen solely due to chance. There is only a very low chance of such a result occurring if the null hypothesis is true in the population.

This means that you believe the meditation intervention, rather than random factors, directly caused the increase in test scores. Example: Interpret your results (correlational study) You compare your p value of 0.001 to your significance threshold of 0.05. With a p value under this threshold, you can reject the null hypothesis. This indicates a statistically significant correlation between parental income and GPA in male college students.

Note that correlation doesn’t always mean causation, because there are often many underlying factors contributing to a complex variable like GPA. Even if one variable is related to another, this may be because of a third variable influencing both of them, or indirect links between the two variables.

Effect size

A statistically significant result doesn’t necessarily mean that there are important real life applications or clinical outcomes for a finding.

In contrast, the effect size indicates the practical significance of your results. It’s important to report effect sizes along with your inferential statistics for a complete picture of your results. You should also report interval estimates of effect sizes if you’re writing an APA style paper .

With a Cohen’s d of 0.72, there’s medium to high practical significance to your finding that the meditation exercise improved test scores. Example: Effect size (correlational study) To determine the effect size of the correlation coefficient, you compare your Pearson’s r value to Cohen’s effect size criteria.

Decision errors

Type I and Type II errors are mistakes made in research conclusions. A Type I error means rejecting the null hypothesis when it’s actually true, while a Type II error means failing to reject the null hypothesis when it’s false.

You can aim to minimize the risk of these errors by selecting an optimal significance level and ensuring high power . However, there’s a trade-off between the two errors, so a fine balance is necessary.

Frequentist versus Bayesian statistics

Traditionally, frequentist statistics emphasizes null hypothesis significance testing and always starts with the assumption of a true null hypothesis.

However, Bayesian statistics has grown in popularity as an alternative approach in the last few decades. In this approach, you use previous research to continually update your hypotheses based on your expectations and observations.

Bayes factor compares the relative strength of evidence for the null versus the alternative hypothesis rather than making a conclusion about rejecting the null hypothesis or not.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Likert scale

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Framing effect

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hostile attribution bias

- Affect heuristic

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Descriptive Statistics | Definitions, Types, Examples

- Inferential Statistics | An Easy Introduction & Examples

- Choosing the Right Statistical Test | Types & Examples

More interesting articles

- Akaike Information Criterion | When & How to Use It (Example)

- An Easy Introduction to Statistical Significance (With Examples)

- An Introduction to t Tests | Definitions, Formula and Examples

- ANOVA in R | A Complete Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Central Limit Theorem | Formula, Definition & Examples

- Central Tendency | Understanding the Mean, Median & Mode

- Chi-Square (Χ²) Distributions | Definition & Examples

- Chi-Square (Χ²) Table | Examples & Downloadable Table

- Chi-Square (Χ²) Tests | Types, Formula & Examples

- Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test | Formula, Guide & Examples

- Chi-Square Test of Independence | Formula, Guide & Examples

- Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Calculation & Interpretation

- Correlation Coefficient | Types, Formulas & Examples

- Frequency Distribution | Tables, Types & Examples

- How to Calculate Standard Deviation (Guide) | Calculator & Examples

- How to Calculate Variance | Calculator, Analysis & Examples

- How to Find Degrees of Freedom | Definition & Formula

- How to Find Interquartile Range (IQR) | Calculator & Examples

- How to Find Outliers | 4 Ways with Examples & Explanation

- How to Find the Geometric Mean | Calculator & Formula

- How to Find the Mean | Definition, Examples & Calculator

- How to Find the Median | Definition, Examples & Calculator

- How to Find the Mode | Definition, Examples & Calculator

- How to Find the Range of a Data Set | Calculator & Formula

- Hypothesis Testing | A Step-by-Step Guide with Easy Examples

- Interval Data and How to Analyze It | Definitions & Examples

- Levels of Measurement | Nominal, Ordinal, Interval and Ratio

- Linear Regression in R | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Missing Data | Types, Explanation, & Imputation

- Multiple Linear Regression | A Quick Guide (Examples)

- Nominal Data | Definition, Examples, Data Collection & Analysis

- Normal Distribution | Examples, Formulas, & Uses

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions & Examples

- One-way ANOVA | When and How to Use It (With Examples)

- Ordinal Data | Definition, Examples, Data Collection & Analysis

- Parameter vs Statistic | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) | Guide & Examples

- Poisson Distributions | Definition, Formula & Examples

- Probability Distribution | Formula, Types, & Examples

- Quartiles & Quantiles | Calculation, Definition & Interpretation

- Ratio Scales | Definition, Examples, & Data Analysis

- Simple Linear Regression | An Easy Introduction & Examples

- Skewness | Definition, Examples & Formula

- Statistical Power and Why It Matters | A Simple Introduction

- Student's t Table (Free Download) | Guide & Examples

- T-distribution: What it is and how to use it

- Test statistics | Definition, Interpretation, and Examples

- The Standard Normal Distribution | Calculator, Examples & Uses

- Two-Way ANOVA | Examples & When To Use It

- Type I & Type II Errors | Differences, Examples, Visualizations

- Understanding Confidence Intervals | Easy Examples & Formulas

- Understanding P values | Definition and Examples

- Variability | Calculating Range, IQR, Variance, Standard Deviation

- What is Effect Size and Why Does It Matter? (Examples)

- What Is Kurtosis? | Definition, Examples & Formula

- What Is Standard Error? | How to Calculate (Guide with Examples)

What is your plagiarism score?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Being able to summarize and analyze a research article is important not only for showing your professor that you have understood your assigned reading, but it also is the first step to learning how to write your own research papers and literature reviews.

In writing up your critical essay, you will need to include the following: Summary of the article you are critiquing: this shows you understood it. Provide a brief overview of what the article was trying to do (i.e., the problem), methods, if relevant, and the thesis or findings.

Plan, organize, and write an effective inquiry-based paper that investigates a research study, evaluates evidence, expounds on the author’s main ideas, and presents an argument concerning the significance and impact of the research in a clear and concise manner;

To draw valid conclusions, statistical analysis requires careful planning from the very start of the research process. You need to specify your hypotheses and make decisions about your research design, sample size, and sampling procedure.

How To Critically Analyze A Research Paper - YouTube. Bitesize Bio. 1.21K subscribers. Subscribed. 58. 5.6K views 1 year ago. Originally broadcast in 2018....

An important part of a careful and critical reading of a research article is understanding and evaluating these elements. The more effectively an author builds each of these elements, the stronger the research paper will be. However, you will find that some authors do not necessarily present strong,