- Humanities ›

- Writing Essays ›

How to Start an Essay: 13 Engaging Strategies

ThoughtCo / Hugo Lin

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

There are countless ways to start an essay effectively. A solid introductory paragraph both informs and motivates. It lets readers know what your piece is about and it encourages them to keep reading.

For folks new to learning how to start an essay, here are 13 introductory strategies accompanied by examples from a wide range of professional writers.

State Your Thesis Briefly and Directly

One straightforward way to begin is to get right to the point. But avoid making your thesis a bald announcement, such as "This essay is about...".

"It is time, at last, to speak the truth about Thanksgiving, and the truth is this. Thanksgiving is really not such a terrific holiday...." (Michael J. Arlen, "Ode to Thanksgiving." The Camera Age: Essays on Television . Penguin, 1982)

Pose a Question Related to Your Subject

A thought-provoking way to start an essay is by asking a relevant question that needs to be unpacked. Follow up the question with an answer, or an invitation for your readers to answer the question.

"What is the charm of necklaces? Why would anyone put something extra around their neck and then invest it with special significance? A necklace doesn't afford warmth in cold weather, like a scarf, or protection in combat, like chain mail; it only decorates. We might say, it borrows meaning from what it surrounds and sets off, the head with its supremely important material contents, and the face, that register of the soul. When photographers discuss the way in which a photograph reduces the reality it represents, they mention not only the passage from three dimensions to two, but also the selection of a point de vue that favors the top of the body rather than the bottom, and the front rather than the back. The face is the jewel in the crown of the body, and so we give it a setting." (Emily R. Grosholz, "On Necklaces." Prairie Schooner , Summer 2007)

State an Interesting Fact About Your Subject

Leading with a fact that draws readers in immediately can grab their attention effectively.

" The peregrine falcon was brought back from the brink of extinction by a ban on DDT, but also by a peregrine falcon mating hat invented by an ornithologist at Cornell University. If you cannot buy this, Google it. Female falcons had grown dangerously scarce. A few wistful males nevertheless maintained a sort of sexual loitering ground. The hat was imagined, constructed, and then forthrightly worn by the ornithologist as he patrolled this loitering ground, singing, Chee-up! Chee-up! and bowing like an overpolite Japanese Buddhist trying to tell somebody goodbye...." (David James Duncan, "Cherish This Ecstasy." The Sun , July 2008)

Present Your Thesis as a Recent Discovery or Revelation

"I've finally figured out the difference between neat people and sloppy people. The distinction is, as always, moral. Neat people are lazier and meaner than sloppy people." (Suzanne Britt Jordan, "Neat People vs. Sloppy People." Show and Tell . Morning Owl Press, 1983)

Briefly Describe the Primary Setting of Your Essay

"It was in Burma, a sodden morning of the rains. A sickly light, like yellow tinfoil, was slanting over the high walls into the jail yard. We were waiting outside the condemned cells, a row of sheds fronted with double bars, like small animal cages. Each cell measured about ten feet by ten and was quite bare within except for a plank bed and a pot of drinking water. In some of them brown silent men were squatting at the inner bars, with their blankets draped round them. These were the condemned men, due to be hanged within the next week or two." (George Orwell, "A Hanging," 1931)

Recount an Incident That Dramatizes Your Subject

Sharing an incident from your life or history in general is an impactful way to start an essay.

"One October afternoon three years ago while I was visiting my parents, my mother made a request I dreaded and longed to fulfill. She had just poured me a cup of Earl Grey from her Japanese iron teapot, shaped like a little pumpkin; outside, two cardinals splashed in the birdbath in the weak Connecticut sunlight. Her white hair was gathered at the nape of her neck, and her voice was low. “Please help me get Jeff’s pacemaker turned off,” she said, using my father’s first name. I nodded, and my heart knocked." (Katy Butler, "What Broke My Father's Heart." The New York Times Magazine , June 18, 2010)

Use the Narrative Strategy of Delay

The narrative strategy of delay allows you to put off identifying your subject just long enough to pique your readers' interest without frustrating them.

"They woof. Though I have photographed them before, I have never heard them speak, for they are mostly silent birds. Lacking a syrinx, the avian equivalent of the human larynx, they are incapable of song. According to field guides the only sounds they make are grunts and hisses, though the Hawk Conservancy in the United Kingdom reports that adults may utter a croaking coo and that young black vultures, when annoyed, emit a kind of immature snarl...." (Lee Zacharias, "Buzzards." Southern Humanities Review , 2007)

Use the Historical Present Tense

An effective way to start an essay is to use historical present tense to relate an incident from the past as if it were happening now.

"Ben and I are sitting side by side in the very back of his mother’s station wagon. We face glowing white headlights of cars following us, our sneakers pressed against the back hatch door. This is our joy—his and mine—to sit turned away from our moms and dads in this place that feels like a secret, as though they are not even in the car with us. They have just taken us out to dinner, and now we are driving home. Years from this evening, I won’t actually be sure that this boy sitting beside me is named Ben. But that doesn’t matter tonight. What I know for certain right now is that I love him, and I need to tell him this fact before we return to our separate houses, next door to each other. We are both five." (Ryan Van Meter, "First." The Gettysburg Review , Winter 2008)

Briefly Describe a Process That Leads Into Your Subject

"I like to take my time when I pronounce someone dead. The bare-minimum requirement is one minute with a stethoscope pressed to someone’s chest, listening for a sound that is not there; with my fingers bearing down on the side of someone’s neck, feeling for an absent pulse; with a flashlight beamed into someone’s fixed and dilated pupils, waiting for the constriction that will not come. If I’m in a hurry, I can do all of these in sixty seconds, but when I have the time, I like to take a minute with each task." (Jane Churchon, "The Dead Book." The Sun , February 2009)

Reveal a Secret or Make a Candid Observation

"I spy on my patients. Ought not a doctor to observe his patients by any means and from any stance, that he might the more fully assemble evidence? So I stand in doorways of hospital rooms and gaze. Oh, it is not all that furtive an act. Those in bed need only look up to discover me. But they never do." ( Richard Selzer , "The Discus Thrower." Confessions of a Knife . Simon & Schuster, 1979)

Open with a Riddle, Joke, or Humorous Quotation

A fun way to start an essay is to use a riddle , joke, or humorous quotation that reveals something about your subject.

" Q: What did Eve say to Adam on being expelled from the Garden of Eden? A: 'I think we're in a time of transition.' The irony of this joke is not lost as we begin a new century and anxieties about social change seem rife. The implication of this message, covering the first of many periods of transition, is that change is normal; there is, in fact, no era or society in which change is not a permanent feature of the social landscape...." (Betty G. Farrell, Family: The Making of an Idea, an Institution, and a Controversy in American Culture . Westview Press, 1999)

Offer a Contrast Between Past and Present

"As a child, I was made to look out the window of a moving car and appreciate the beautiful scenery, with the result that now I don't care much for nature. I prefer parks, ones with radios going chuckawaka chuckawaka and the delicious whiff of bratwurst and cigarette smoke." (Garrison Keillor, "Walking Down The Canyon." Time , July 31, 2000)

Offer a Contrast Between Image and Reality

A compelling way to start an essay is with a contrast between a common misconception and the opposing truth.

"They aren’t what most people think they are. Human eyes, touted as ethereal objects by poets and novelists throughout history, are nothing more than white spheres, somewhat larger than your average marble, covered by a leather-like tissue known as sclera and filled with nature’s facsimile of Jell-O. Your beloved’s eyes may pierce your heart, but in all likelihood they closely resemble the eyes of every other person on the planet. At least I hope they do, for otherwise he or she suffers from severe myopia (near-sightedness), hyperopia (far-sightedness), or worse...." (John Gamel, "The Elegant Eye." Alaska Quarterly Review , 2009)

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- 501 Topic Suggestions for Writing Essays and Speeches

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- Essay Assignment: Descriptive and Informative Profile

- Practice in Supporting a Topic Sentence with Specific Details

- How to Start a Book Report

- What Is Expository Writing?

- An Essay Revision Checklist

- Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing

- 50 Argumentative Essay Topics

- How to Outline and Organize an Essay

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech (With Topic Ideas)

- Writing an Opinion Essay

How To Start a College Essay: 9 Effective Techniques

This post was co-written by me (Ethan) and Luci Jones (Brown University, CO ‘23).

How to start a college essay TABLE OF CONTENTS

The full hemingway, the mini hemingway, the philosophical question, the confession, the trailer thesis, the fascinating concept, the random personal fun fact, the shocking image.

In anything you do, there’s a special, pivotal moment.

I don’t mean the moment when inspiration strikes or the last brushstroke is painted or the audience oohs and ahs over the final product. The point in time we’re talking about here is the Moment When You Do The Darn Thing (DTDT for short). It’s when you get off the couch, stop binging Netflix , and take action. It’s when you put pencil to paper, fingers to keyboard, or *insert whatever other analogy feels applicable here.*

For many, getting started is the hardest part of anything. And that’s understandable. First, because it turns whatever you’re doing into a reality, which raises the stakes. Second, because where you start can easily dictate the quality of where you end up.

College essays have their own special brand of DTDT. Knowing how to begin a college essay is daunting. It can be hard to write an engaging, authentic opener. But without an interesting hook, you risk getting lost in a vast sea of applications. To this end, we’ve put together some techniques about how to start a college essay to make your DTDT moment a little smoother and a little less stressful.

I say “probably” because I’m about to share a few overused techniques that I don’t recommend. Having said that, it is possible to pull them off—they’re just really hard to do well.

The Overly Grand Ambiguous Statement: From a distance, it might seem nice to talk about why all of humankind has felt some type of way for as long as history has existed. (Examples: “Many great thinkers have existed in our nation’s history” or “The key to a successful endeavor is perseverance.”) But these kinds of overly generalized or impersonal grand statements get lost easily in the crowd because they don’t tell the reader much about you. And without a connection to you, there’s not much reason for them to continue reading.

Going Meta: As cool as it may seem to demonstrate to your audience that you are aware of how you’re writing your essay in the moment you’re writing it, it’s less cool to college admissions officers who read meta stuff like that all the time. There are other, more subtle ways to demonstrate self-awareness in your intro rather than to open your essay with some variation of, “I stare at the blank screen...” or, worse, “When I was asked to write this personal statement, at first I wasn’t sure how to begin.” Note that the meta essay can sometimes work (you’ll see a couple examples below), but has a higher degree of difficulty.

The Quote: While quoting famous people who have said something cool in the past may seem like an appealing way to start your essay, remember that colleges want to hear YOUR thoughts. Don’t use the words of another person to stand in for your own opinions or insights. You have cool things to say. It may just take a little while to discover what those things are.

The Too-Obvious Thesis That Spoils the Ending of the Movie (i.e. Your Essay): What if Avengers: Infinity War had opened with a voiceover from the director saying, “This is a film about how Thanos collects all the infinity stones and destroys half the population.” (Aaaaaand this is your too-late spoiler alert. Sorry. But don’t worry, they go back in time and undo it in Endgame . Oh, also spoiler.) That would’ve sucked. That’s what it feels like, though, if you start your essay with something like, “I want to be a veterinarian because I care about animals and the environment.” I read a sentence like that and I go, “Cool, thanks, now I can save myself the three minutes it would’ve taken to read the essay. Thank you, next.” While you may want to have that sentence in mind so you know what you’re trying to get across (this is called a logline), just don’t give away the whole thing. Instead, start your essay with something to pique our interest. How? We’re about to share 9 ways.

Want to read a few more college essay tips? Check out this huge list from admissions experts.

9 WAYS TO START A COLLEGE ESSAY:

An image-based description that focuses on a particular moment and doesn’t explain much—at least not right away. This technique lets dialogue, actions, or details speak for themselves.

(Note that there are many other authors that do this — it’s part of great writing — but my little brother suggested Hemingway and I kinda’ liked the sound of it.)

Example:

Every Saturday morning, I’d awaken to the smell of crushed garlic and piquant pepper. I would stumble into the kitchen to find my grandma squatting over a large silver bowl, mixing fat lips of fresh cabbages with garlic, salt, and red pepper.

Why It Works: In this intro, the author paints a very visceral picture of waking up in the morning to the smell of her grandmother’s traditional Korean cooking. Through the careful word choice (“piquant pepper,” “fat lips of fresh cabbages,” etc.), we get a sense that something important is happening, even if we don’t know what it is yet. But this one can be difficult to pull off if you don’t help the reader understand why you’ve described what you’ve described. Read the rest of the essay here .

Which brings us to...

An image-based description, perhaps 1-3 sentences in length, that focuses on a particular moment and then follows up with a sentence that explains, comments on, or somehow provides context for what is being described.

Take a look at how this can happen by just adding one sentence to the example above (see bolded line below):

Every Saturday morning, I’d awaken to the smell of crushed garlic and piquant pepper. I would stumble into the kitchen to find my grandma squatting over a large silver bowl, mixing fat lips of fresh cabbages with garlic, salt, and red pepper. That was how the delectable Korean dish, kimchi, was born every weekend at my home.

Why it Works: This single sentence hints at some of the author’s core values—culture, ritual, family—without giving too much away about where the essay is headed. Like any good intro, this one creates more questions that answers. (Read the rest of the essay here .)

Another example:

They covered the precious mahogany coffin with a brown amalgam of rocks, decomposed organisms, and weeds. It was my turn to take the shovel, but I felt too ashamed to dutifully send her off when I had not properly said goodbye. I refused to throw dirt on her. I refused to let go of my grandmother, to accept a death I had not seen coming, to believe that an illness could not only interrupt, but steal a beloved life.

Why It Works: The author drops us right into the middle of something we know nothing about, yet it invites us to care. How? The specifics. The details she notices and the resistance she’s feeling help to put us in her shoes. This means we don’t just feel sympathy, we feel empathy . And that empathetic connection heightens the stakes for us by raising questions: How did her grandmother die? Why can’t the author let her go? Why is she angry? (Spoiler: It turns out she’s more angry at herself than anyone else. Read the rest of the essay here .)

The author begins with information that creates certain expectations about them before taking us in a surprising direction.

Growing up, my world was basketball. My summers were spent between the two solid black lines. My skin was consistently tan in splotches and ridden with random scratches. My wardrobe consisted mainly of track shorts, Nike shoes, and tournament t-shirts. Gatorade and Fun Dip were my pre-game snacks. The cacophony of rowdy crowds, ref whistles, squeaky shoes, and scoreboard buzzers was a familiar sound. I was the team captain of almost every team I played on—familiar with the Xs and Os of plays, commander of the court, and the coach’s right hand girl. But that was only me on the surface. Deep down I was an East-Asian influenced bibliophile and a Young Adult fiction writer.

Why It Works: We’re introduced to the author as a basketball superstar, the queen of the court, a sports fanatic—and at this point the reader may even be making assumptions about this author’s identity based on her initial description of herself. However, in one sentence, the writer takes us in a completely unexpected direction. This plays with audience expectations and demonstrates that she has a good degree of self awareness about the layers of her identity. After having our expectations thrown for a loop, we can’t help but wonder more about who exactly this person is (and if you want to know like I did, read the rest of this essay here ).

Another example:

I am on Oxford Academy’s Speech and Debate Team, in both the Parliamentary Debate division and the Lincoln-Douglass debate division. I write screenplays, short stories, and opinionated blogs and am a regular contributor to my school literary magazine, The Gluestick. I have accumulated over 300 community service hours that includes work at homeless shelters, libraries, and special education youth camps. I have been evaluated by the College Board and have placed within the top percentile. But I am not any of these things. I am not a test score, nor a debater, nor a writer. I am an anti-nihilist punk rock philosopher. And I became so when I realized three things:

Why It Works: He basically tears up his (impressive) resume in the first few sentences and says, “That’s not me! Here’s the real me…” and as a result we wonder, “How does one become an anti-nihilist punk rock philosopher? And what are the three things??” (Read the rest here .)

Ask a question that you won’t (and probably can’t) answer in your essay. This gives you a chance to show how your brilliant brain works, plus keeps us hooked as you explore possible answers/solutions.

Does every life matter? Because it seems like certain lives matter more than others, especially when it comes to money.

Why it Works: It raises a complex, interesting question and poses a controversial idea: that we treat some lives as though they matter more than others. We wonder: “Is that true? Could it be? Say more…” Heads-up: This one can veer into the “Overly Grand Ambiguous Statement” opening if you’re not careful. Click here to read the rest of the essay mentioned above, which by the way took him a long time to refine—as this approach is not easy to pull off.

Begin by admitting something you might be judged (or judge yourself) for.

Example:

I have been pooped on many times. I mean this in the most literal sense possible. I have been pooped on by pigeons and possums, house finches and hawks, egrets and eastern grays. (Read the rest here .)

Why it Works: Shows vulnerability, but also in many cases intrigues us to learn more.

Here is a secret that no one in my family knows: I shot my brother when I was six. Luckily, it was a BB gun. But to this day, my older brother Jonathan does not know who shot him. And I have finally promised myself to confess this eleven year old secret to him after I write this essay.

Why It Works: This is a super vulnerable to admit and raises all sorts of questions for us: Why did he shoot his brother? Why hasn’t he confessed it to him? What will his brother say once he tells him? (Fun fact: This essay actually breaks the “don’t start with a quote” rule. Here’s the rest if you wanna’ read it.)

A contextualizing 1-2-sentences (often at the end of the first paragraph) to ground the essay by giving us a sneak peek at what’s to come in the essay—but that do NOT give away the ending.

Example (I’ve marked it in bold below at the end of the first paragraph):

Six years ago, a scrawny twelve year old kid took his first steps into Home Depot: the epitome of manliness. As he marched through the wood section, his eyes scrolled past the options. Red Oak? No, too ubiquitous. Pine? No, too banal. Mahogany? Perfect, it would nicely complement his walls. As days went on, the final product was almost ready. 91 degree angles had been perfected to 90. Drawer slides had been lubricated ten times over. Finally, the masterpiece was finished, and the little boy couldn’t help but smile. A scrawny 12-year-old kid had become a scrawny 12-year-old man. This desk I sit at has not only seen me through the last six years, but its story and the story of the objects I keep on it provide a foundation for my future pursuits.

Why It Works: As we read the first few sentences of this paragraph we might wonder, “Where is this going?” But this sentence sets us at ease and—again, without giving too much away—gives us a sense of what’s to come. We know that we’re going to learn about the author and his future through the objects on his desk. Great! It also signals to the reader “Don’t worry, you’re in good hands. I’m still aware of the task at hand.”

Begin with a concept that’s unusual, paradoxical, and/or marked a turning point in your thinking. This is often followed up with context explaining where the concept came from and why the author is considering it.

Crayfish can turn their red blood cells into precursor neuronal cells, I read in shock. The scientific paper, published in Cell 2014, outlined the process where crayfish could regenerate lost eyestalks or olfactory (smell and odor) nerves with their blood – they could see and smell again! It seemed unfair from an evolutionary standpoint. Humans, who were so much larger than a 7-ounce crayfish, couldn’t use their abundant blood to fix their brain damage.

Why It Works: This opening signals to the reader that the author is: a) someone who has read quite a bit, b) curious, and c) knows, as I like to say, “some stuff about some stuff.” In this case, she knows some science stuff.

Do you know some stuff about some stuff? If so, a little geeky language can help signal this to the reader. Don’t overdo it, though, or it can seem showy.

FYI: I see this more often at the start of great essays than personal statements, as this can often lead to an essay that’s more heady/intellectual and less vulnerable/personal. A variation on this that’s a bit more personal is the...

Begin with a strange fact about yourself to grab our attention. Then go on to say why it’s meaningful. Example:

I subscribe to what the New York Times dubs “the most welcomed piece of daily e-mail in cyberspace.” Cat pictures? Kardashian updates? Nope: A Word A Day.

(Read the rest here .)

Why It Works: It pulls us in by making us think, “Oh, that’s cool!” and then wondering, “Okay, where is this going?”

Grab our attention with an incredibly specific and arresting image or sentence. Then tell us why it matters.

Smeared blood, shredded feathers. Clearly, the bird was dead. But wait, the slight fluctuation of its chest, the slow blinking of its shiny black eyes. No, it was alive.

Why It Works: This style subtly highlights the writing talent of the author without drawing attention away from the content of the story. In this example, the staccatoed sentence fragments convey a sense of halting anxiety and also mimic the movement of the bird’s chest as it struggles to breathe. All sorts of questions come up: What happened to the bird? What will the author do? (Read the rest of the essay here .)

February 2011– My brothers and I were showing off our soccer dribbling skills in my grandfather’s yard when we heard gunshots and screaming in the distance. We paused and listened, confused by sounds we had only ever heard on the news or in movies. My mother rushed out of the house and ordered us inside. The Arab Spring had come to Bahrain.

(Read the rest of the essay here .)

Bowing down to the porcelain god, I emptied the contents of my stomach. Foaming at the mouth, I was ready to pass out. My body couldn’t stop shaking as I gasped for air, and the room started spinning. (Read the rest of the essay here .)

There are, of course, many more kinds of openings—and I’ll add to this post as I discover new ones.

We get it, writing a standout introduction is easier said than done. Hopefully though, after seeing some examples of dynamic and thoughtful intros that used our techniques, you’re inspired to brainstorm some of your own . You’ve got this. DTDT has never looked so good.

Have a great college essay opening or a new type of opening you’d like to suggest? Share it in the comments below!

This post was co-written by me (Ethan) and Luci Jones (Brown University, CO ‘23). Luci took my How to Write a Personal Statement course last year. The essay that she produced was so good and her writing was so beautiful, I’ve asked her to help me co-write this blog post with me, create a few techniques for writing a great introduction, and analyze why they work so well.

How to Write an Essay Introduction (with Examples)

The introduction of an essay plays a critical role in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. It sets the stage for the rest of the essay, establishes the tone and style, and motivates the reader to continue reading.

Table of Contents

What is an essay introduction , what to include in an essay introduction, how to create an essay structure , step-by-step process for writing an essay introduction , how to write an essay introduction paragraph with paperpal – step -by -step, how to write a hook for your essay , how to include background information , how to write a thesis statement .

- Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

- Expository Essay Introduction Example

Literary Analysis Essay Introduction Example

Check and revise – checklist for essay introduction , key takeaways , frequently asked questions .

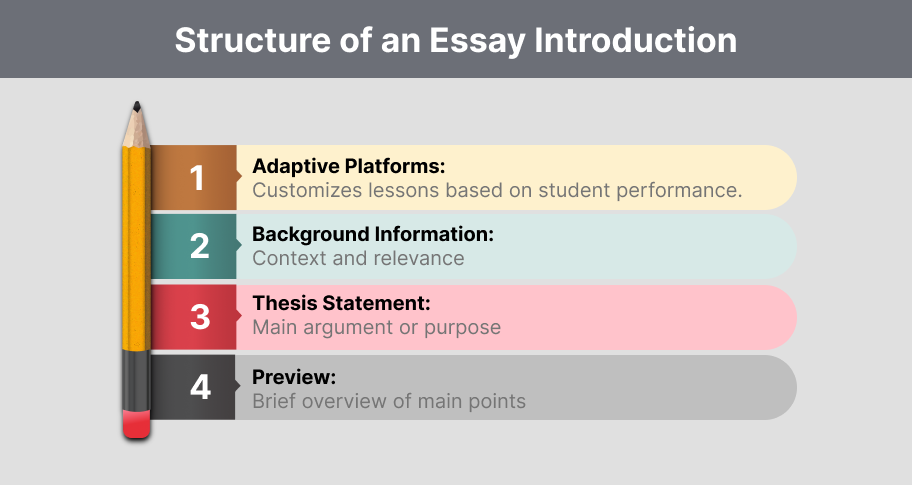

An introduction is the opening section of an essay, paper, or other written work. It introduces the topic and provides background information, context, and an overview of what the reader can expect from the rest of the work. 1 The key is to be concise and to the point, providing enough information to engage the reader without delving into excessive detail.

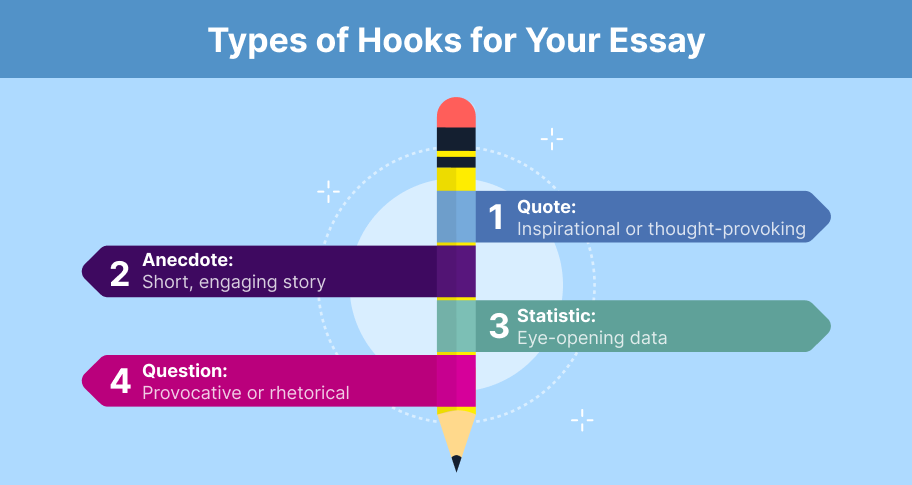

The essay introduction is crucial as it sets the tone for the entire piece and provides the reader with a roadmap of what to expect. Here are key elements to include in your essay introduction:

- Hook : Start with an attention-grabbing statement or question to engage the reader. This could be a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or a compelling anecdote.

- Background information : Provide context and background information to help the reader understand the topic. This can include historical information, definitions of key terms, or an overview of the current state of affairs related to your topic.

- Thesis statement : Clearly state your main argument or position on the topic. Your thesis should be concise and specific, providing a clear direction for your essay.

Before we get into how to write an essay introduction, we need to know how it is structured. The structure of an essay is crucial for organizing your thoughts and presenting them clearly and logically. It is divided as follows: 2

- Introduction: The introduction should grab the reader’s attention with a hook, provide context, and include a thesis statement that presents the main argument or purpose of the essay.

- Body: The body should consist of focused paragraphs that support your thesis statement using evidence and analysis. Each paragraph should concentrate on a single central idea or argument and provide evidence, examples, or analysis to back it up.

- Conclusion: The conclusion should summarize the main points and restate the thesis differently. End with a final statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. Avoid new information or arguments.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an essay introduction:

- Start with a Hook : Begin your introduction paragraph with an attention-grabbing statement, question, quote, or anecdote related to your topic. The hook should pique the reader’s interest and encourage them to continue reading.

- Provide Background Information : This helps the reader understand the relevance and importance of the topic.

- State Your Thesis Statement : The last sentence is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be clear, concise, and directly address the topic of your essay.

- Preview the Main Points : This gives the reader an idea of what to expect and how you will support your thesis.

- Keep it Concise and Clear : Avoid going into too much detail or including information not directly relevant to your topic.

- Revise : Revise your introduction after you’ve written the rest of your essay to ensure it aligns with your final argument.

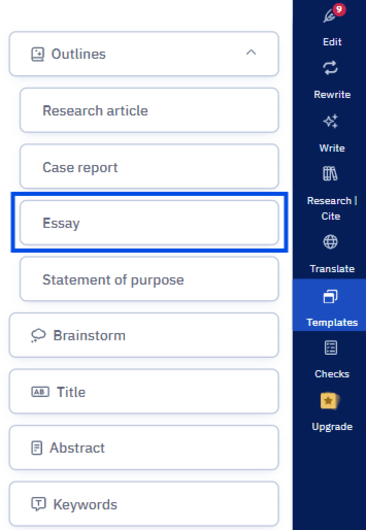

Unsure of how to start your essay introduction? Leverage Paperpal’s Generative AI templates to provide a base for your essay introduction. Here’s an example of an essay outline generated by Paperpal.

Use Paperpal’s Preditive AI writing features to maintain your writing flow

This is one of the key steps in how to write an essay introduction. Crafting a compelling hook is vital because it sets the tone for your entire essay and determines whether your readers will stay interested. A good hook draws the reader in and sets the stage for the rest of your essay.

- Avoid Dry Fact : Instead of simply stating a bland fact, try to make it engaging and relevant to your topic. For example, if you’re writing about the benefits of exercise, you could start with a startling statistic like, “Did you know that regular exercise can increase your lifespan by up to seven years?”

- Avoid Using a Dictionary Definition : While definitions can be informative, they’re not always the most captivating way to start an essay. Instead, try to use a quote, anecdote, or provocative question to pique the reader’s interest. For instance, if you’re writing about freedom, you could begin with a quote from a famous freedom fighter or philosopher.

- Do Not Just State a Fact That the Reader Already Knows : This ties back to the first point—your hook should surprise or intrigue the reader. For Here’s an introduction paragraph example, if you’re writing about climate change, you could start with a thought-provoking statement like, “Despite overwhelming evidence, many people still refuse to believe in the reality of climate change.”

Write essays 2x faster with Paperpal. Try for free

Including background information in the introduction section of your essay is important to provide context and establish the relevance of your topic. When writing the background information, you can follow these steps:

- Start with a General Statement: Begin with a general statement about the topic and gradually narrow it down to your specific focus. For example, when discussing the impact of social media, you can begin by making a broad statement about social media and its widespread use in today’s society, as follows: “Social media has become an integral part of modern life, with billions of users worldwide.”

- Define Key Terms : Define any key terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to your readers but are essential for understanding your argument.

- Provide Relevant Statistics: Use statistics or facts to highlight the significance of the issue you’re discussing. For instance, “According to a report by Statista, the number of social media users is expected to reach 4.41 billion by 2025.”

- Discuss the Evolution: Mention previous research or studies that have been conducted on the topic, especially those that are relevant to your argument. Mention key milestones or developments that have shaped its current impact. You can also outline some of the major effects of social media. For example, you can briefly describe how social media has evolved, including positives such as increased connectivity and issues like cyberbullying and privacy concerns.

- Transition to Your Thesis: Use the background information to lead into your thesis statement, which should clearly state the main argument or purpose of your essay. For example, “Given its pervasive influence, it is crucial to examine the impact of social media on mental health.”

A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, or other type of academic writing. It appears near the end of the introduction. Here’s how to write a thesis statement:

- Identify the topic: Start by identifying the topic of your essay. For example, if your essay is about the importance of exercise for overall health, your topic is “exercise.”

- State your position: Next, state your position or claim about the topic. This is the main argument or point you want to make. For example, if you believe that regular exercise is crucial for maintaining good health, your position could be: “Regular exercise is essential for maintaining good health.”

- Support your position: Provide a brief overview of the reasons or evidence that support your position. These will be the main points of your essay. For example, if you’re writing an essay about the importance of exercise, you could mention the physical health benefits, mental health benefits, and the role of exercise in disease prevention.

- Make it specific: Ensure your thesis statement clearly states what you will discuss in your essay. For example, instead of saying, “Exercise is good for you,” you could say, “Regular exercise, including cardiovascular and strength training, can improve overall health and reduce the risk of chronic diseases.”

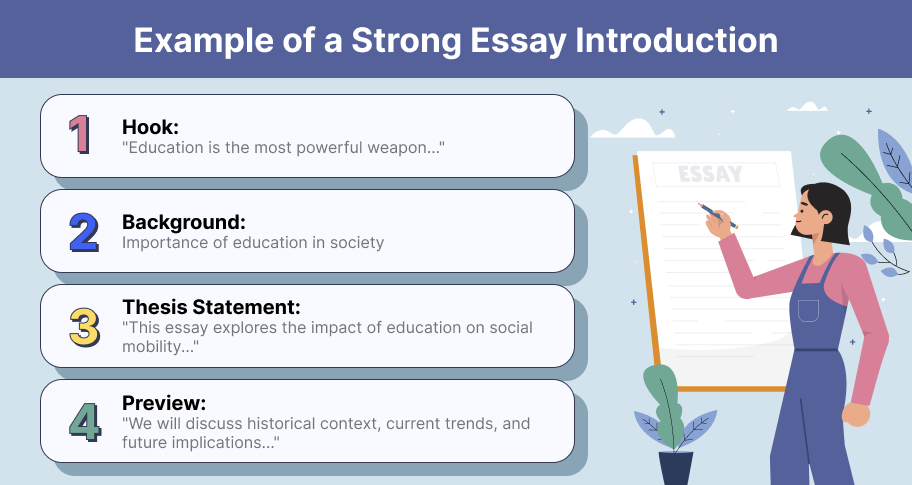

Examples of essay introduction

Here are examples of essay introductions for different types of essays:

Argumentative Essay Introduction Example:

Topic: Should the voting age be lowered to 16?

“The question of whether the voting age should be lowered to 16 has sparked nationwide debate. While some argue that 16-year-olds lack the requisite maturity and knowledge to make informed decisions, others argue that doing so would imbue young people with agency and give them a voice in shaping their future.”

Expository Essay Introduction Example

Topic: The benefits of regular exercise

“In today’s fast-paced world, the importance of regular exercise cannot be overstated. From improving physical health to boosting mental well-being, the benefits of exercise are numerous and far-reaching. This essay will examine the various advantages of regular exercise and provide tips on incorporating it into your daily routine.”

Text: “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee

“Harper Lee’s novel, ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ is a timeless classic that explores themes of racism, injustice, and morality in the American South. Through the eyes of young Scout Finch, the reader is taken on a journey that challenges societal norms and forces characters to confront their prejudices. This essay will analyze the novel’s use of symbolism, character development, and narrative structure to uncover its deeper meaning and relevance to contemporary society.”

- Engaging and Relevant First Sentence : The opening sentence captures the reader’s attention and relates directly to the topic.

- Background Information : Enough background information is introduced to provide context for the thesis statement.

- Definition of Important Terms : Key terms or concepts that might be unfamiliar to the audience or are central to the argument are defined.

- Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement presents the main point or argument of the essay.

- Relevance to Main Body : Everything in the introduction directly relates to and sets up the discussion in the main body of the essay.

Write strong essays in academic English with Paperpal. Try it for free

Writing a strong introduction is crucial for setting the tone and context of your essay. Here are the key takeaways for how to write essay introduction: 3

- Hook the Reader : Start with an engaging hook to grab the reader’s attention. This could be a compelling question, a surprising fact, a relevant quote, or an anecdote.

- Provide Background : Give a brief overview of the topic, setting the context and stage for the discussion.

- Thesis Statement : State your thesis, which is the main argument or point of your essay. It should be concise, clear, and specific.

- Preview the Structure : Outline the main points or arguments to help the reader understand the organization of your essay.

- Keep it Concise : Avoid including unnecessary details or information not directly related to your thesis.

- Revise and Edit : Revise your introduction to ensure clarity, coherence, and relevance. Check for grammar and spelling errors.

- Seek Feedback : Get feedback from peers or instructors to improve your introduction further.

The purpose of an essay introduction is to give an overview of the topic, context, and main ideas of the essay. It is meant to engage the reader, establish the tone for the rest of the essay, and introduce the thesis statement or central argument.

An essay introduction typically ranges from 5-10% of the total word count. For example, in a 1,000-word essay, the introduction would be roughly 50-100 words. However, the length can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the overall length of the essay.

An essay introduction is critical in engaging the reader and providing contextual information about the topic. To ensure its effectiveness, consider incorporating these key elements: a compelling hook, background information, a clear thesis statement, an outline of the essay’s scope, a smooth transition to the body, and optional signposting sentences.

The process of writing an essay introduction is not necessarily straightforward, but there are several strategies that can be employed to achieve this end. When experiencing difficulty initiating the process, consider the following techniques: begin with an anecdote, a quotation, an image, a question, or a startling fact to pique the reader’s interest. It may also be helpful to consider the five W’s of journalism: who, what, when, where, why, and how. For instance, an anecdotal opening could be structured as follows: “As I ascended the stage, momentarily blinded by the intense lights, I could sense the weight of a hundred eyes upon me, anticipating my next move. The topic of discussion was climate change, a subject I was passionate about, and it was my first public speaking event. Little did I know , that pivotal moment would not only alter my perspective but also chart my life’s course.”

Crafting a compelling thesis statement for your introduction paragraph is crucial to grab your reader’s attention. To achieve this, avoid using overused phrases such as “In this paper, I will write about” or “I will focus on” as they lack originality. Instead, strive to engage your reader by substantiating your stance or proposition with a “so what” clause. While writing your thesis statement, aim to be precise, succinct, and clear in conveying your main argument.

To create an effective essay introduction, ensure it is clear, engaging, relevant, and contains a concise thesis statement. It should transition smoothly into the essay and be long enough to cover necessary points but not become overwhelming. Seek feedback from peers or instructors to assess its effectiveness.

References

- Cui, L. (2022). Unit 6 Essay Introduction. Building Academic Writing Skills .

- West, H., Malcolm, G., Keywood, S., & Hill, J. (2019). Writing a successful essay. Journal of Geography in Higher Education , 43 (4), 609-617.

- Beavers, M. E., Thoune, D. L., & McBeth, M. (2023). Bibliographic Essay: Reading, Researching, Teaching, and Writing with Hooks: A Queer Literacy Sponsorship. College English, 85(3), 230-242.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- How to Write a Good Hook for Essays, with Examples

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

Similarity Checks: The Author’s Guide to Plagiarism and Responsible Writing

Types of plagiarism and 6 tips to avoid it in your writing , you may also like, what are the types of literature reviews , abstract vs introduction: what is the difference , mla format: guidelines, template and examples , machine translation vs human translation: which is reliable..., dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal.

- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

- Study Documents

- Learning Tools

Writing Guides

- Citation Generator

- Flash Card Generator

- Homework Help

- Essay Examples

- Essay Title Generator

- Essay Topic Generator

- Essay Outline Generator

- Flashcard Generator

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Introduction Generator

- Literature Review Generator

- Hypothesis Generator

- Human Editing Service

- Essay Hook Generator

Writing Guides / How to Start an Essay: Tips for Writing a Strong Introduction

How to Start an Essay: Tips for Writing a Strong Introduction

Introduction

The first place you lose a reader is right at the very start. Not the middle. Not the second paragraph. The very first line.

It’s the first impression that matters—which is why the essay hook is so big a deal. It’s the initial greeting, the smile, the posture, the body language. It tells all, reveals all. If your hook has meat on it, you’ll get the bite you desire. If it doesn’t, your essay is going to sink like a log.

Writing an essay introduction doesn’t have to be hard. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll go over all the ins and outs of how to start an essay. We’ll cover all the essay introduction sins you might be tempted to commit.

We’ll show you how to launch right into it with a compelling fact, quote or question.

Stick with us and you’ll be a paragon of essay-writing virtue.

The goal of this article is to help readers craft effective essay introductions.

Understanding the Essay Introduction

Definition of an essay introduction.

An essay introduction is like welcome center when you enter a new state on the expressway. You can see your location on the map, get an idea of all the neat things to do and see, get some refreshment, and head out. In an essay, the introduction sets the course, establishes the tone, pulls the reader in, and conveys the main idea or point.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Obviously, introductions matter. If you show up at a party and no one is there to receive you or introduce you to others, you might spend an uncomfortable evening sitting alone. A good essay introduction brings two minds together—yours (the writer) and theirs (the reader). It shows the reader that you have thoughtfully considered him as a guest in the house of your mind, and are prepared to deliver a reasonable greeting, show him around, get him seated, and make him comfortable. It shows you know how to make what you have to say appear relevant to your audience.

Overview of What a Strong Introduction Should Achieve

A strong introduction should create in the reader a desire to read on. The intro is like the “hors d’oeuvres”—which is French for “outside the main work”—which is to say: the intro is not the meat but rather the morsel before the main dish. It should give a sense of what’s to come and whet the appetite for more. When writing an essay introduction, the goal is to conclude with a thesis statement , which conveys the precise purpose of the essay. The whole idea of how to start an essay is found in this simple analogy of the appetizer as prelude to the main course.

View 120,000+ High Quality Essay Examples

Learn-by-example to improve your academic writing

Key Elements of an Essay Introduction

The hook: different types of hooks.

The hook is the first sentence of your essay . It is usually something as simple as a quote, statistic, or question designed to pique the reader’s interest. With longer essays it could be all right to tell an anecdote as a hook.

The point is that a well-chosen hook will stir your reader’s imagination.

- Quotes: Starting with a relevant quote can add authority and context to your essay. For example, “ Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere ,” is a quote from Martin Luther King Jr. that can be used to establish a powerful moral tone for an essay on social justice.

- Anecdotes: A brief, interesting story or personal experience can draw readers in by making the topic relatable, human, humorous or dramatic.

- Statistics: Presenting a surprising or shocking statistic can instantly capture attention. For example, “ Nearly 70% of adults experience imposter syndrome at some point in their careers. “

- Questions: Asking a thought-provoking question encourages readers to think critically and engage with the topic. For example, “What would you do if you knew this was your last day on earth?”

Background Information: How to Provide Context and Relevance

After the hook, your reader will need some background information that puts your subject into its proper context. You might share historical background, definitions, or an overview of the current state of the topic. Basically, this section of the introduction should bridge the gap between the hook and the thesis statement which is to come.

When sharing background information, be mindful not to overwhelm your reader with too much detail. Remember: the body paragraphs are the meat—the intro is just the appetizer. You can use the body to give more background and context if needed. The introduction should be brief and focused—a few short steps from the hook to the thesis. Done!

Thesis Statement: Crafting a Clear and Concise Thesis

The thesis statement is really the distillation of the point of the essay—and therefore it has great importance in your introduction. It presents the main argument or claim of your essay, so that the reader has an idea what to expect. A strong thesis statement is clear, precise, confident, and direct. It may even preview the points that will be discussed in the essay.

For example, in an argumentative essay on healthcare, a strong thesis might be: “Healthcare today is controlled by a cartel of corporations that put profits before people because they know that if they actually healed people and prevented disease their entire industry would go out of business.”

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing an Essay Introduction

Step 1: start with a hook.

Start with a hook that makes your reader want to read on. The hook should be relevant and allow you to get from point A (“Hey, look at this!”) to point B (“Here’s what I have to say now!”). A good hook also sets the tone for the rest of the essay—so a humorous anecdote about barracks life is probably not appropriate for a serious essay on trench warfare.

Step 2: Provide Background Information

After the hook, you’ll need to give some background information. Help the reader understand the context of your essay. By letting your reader know where you are coming from, the reader can orient himself and make quicker sense of what you have to say.

Step 3: State Your Thesis Statement

Say what your point is and how you intend to show it. Simple as that.

Step 4: Preview the Main Points

Don’t go into too much detail here: just quickly—in a few words—list your reasons that support your thesis. For example, “Hamlet is a tragic hero according to Aristotle’s definition , because he is good (virtuous), realistic (flawed), and experiences a fall.”

Step 5: Revise and Refine

Once you have written your introduction, take the time to revise and refine it. This is actually the most important step. Great intros don’t happen by themselves—they take skill, effort, and practice. Look to see that it all flows smoothly and that each element (hook, background information, thesis statement, and preview) is effectively linked. Take out any extraneous information or unnecessary clichés. Keep it sweet and to point.

Examples of Essay Introductions

To help illustrate these concepts discussed, here are examples of introductions for different types of essays and topics.

Essay Types

- Argumentative Essay Example: “Universal Basic Income (UBI) is a progressive policy that proposes providing all citizens with a guaranteed income regardless of their employment status. Advocates argue that UBI can reduce poverty, boost economic security, and provide a safety net in an increasingly automated world. However, two major problems with UBI are how to fund it and how it might hinder stimulating productivity. This essay contends that implementing UBI is a misstep to addressing income inequality and adapting to the future of work, and that instead free education, training, and child care should be offered to people who need it so that they can work.”

- Expository Essay Example: “Renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, are becoming increasingly popular as the world seeks to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels. This essay explores the various types of renewable energy, their benefits for the environment and economy, and the challenges posed in transitioning to a sustainable energy future.”

- Literary Analysis Essay Example: “In George Orwell’s ‘1984,’ the concept of totalitarianism is explored through the dystopian society of Oceania, where the government holds absolute control over every aspect of its citizens’ lives. This essay shows how Orwell uses the symbol of the omnipresent and omnipotent figure of Big Brother, and the concept of ‘Newspeak,’ to describe a regime that operates totally on lies.”

Essay Topics

Air Pollution Example: “Air pollution is cited by the World Health Organization as the main cause of death for 6.7 million people worldwide . Clearly, the consequences of air pollution are far-reaching, with smog, smoke, and toxins filling the air. This essay looks at the causes, effects, and potential solutions to the problem of air pollution.”

Drug Abuse Example: “Drug abuse is on the rise all over the world, thanks in no small part to the Sackler family and its development of opioids like Oxycontin and Fentanyl. While the courts are having their say regarding the extent to which the Sackler’s Purdue Pharma must pay for this crisis, victims of drug abuse still have to struggle to put their lives back together again. This essay explores the social factors contributing to drug abuse, its impact on families, and the strategies for prevention and treatment.”

Save Water Example: “Have you ever thought about how water is a precious resource that is essential for life, yet is often taken for granted? It may seem odd to think of it, considering that the earth is literally covered with water, but the fact is that water conservation is a serious problem in the world. This essay discusses the reasons why saving water is important, the challenges we face, and the steps that can be taken.”

Social Media Example: “Social media has democratized information and stood legacy media on its head. In that respect, it is a win for the people. On the other hand, it has totally seduced young people and become the whole center of their existence, causing depression and isolation. This essay describes the pros and cons of social media, and discusses how to balance it through moderation and self-control.”

Technology Example: “Technology has literally transformed the planet: even the Amish are using modern tools! As for the rest of us, we engage with smartphones and artificial intelligence on a daily basis, and it is changing our lives, our work, our social interactions, and our ability to think and be productive. This essay shows the benefits and drawbacks of technology, as we move through the 21 st century.”

Sports Example: “Sports! It’s the one topic that gets everyone giddy at trivia night. But more than that—it offers great opportunities for physical health, teamwork, and discipline. However, the world of sports is not without its problems, including issues related to doping and over-commercialization. This essay examines the significance of sports in society, its potential for positive change, and the dangers that surround it.”

Inflation Example: “Inflation is an economic phenomenon that affects the purchasing power of money and the overall stability of an economy. In a nutshell, goods get more expensive while wages remain the same. But what is the cause of inflation? Why does it go away and then come back? The fact is, a lot of it has to do with the central bank’s tendency to print a lot of new money in a short amount of time. This essay goes into the nitty-gritty details of the causes and consequences of inflation, and what people can do to control it.”

Healthcare Example: “Healthcare is an industry that has gotten a free pass for far too long. For all the sickness and poverty in America, you would think we didn’t have any healthcare system at all—yet our country spends more money on healthcare than anywhere else in the world. Do we have healthy people to show for it? Not at all! We have obesity off the charts, opioid epidemics, and the most expensive care ever. This essay will explain how healthcare became a corrupt member of the family of corporate cartels, and what people can do to regain their health holistically and naturally.”

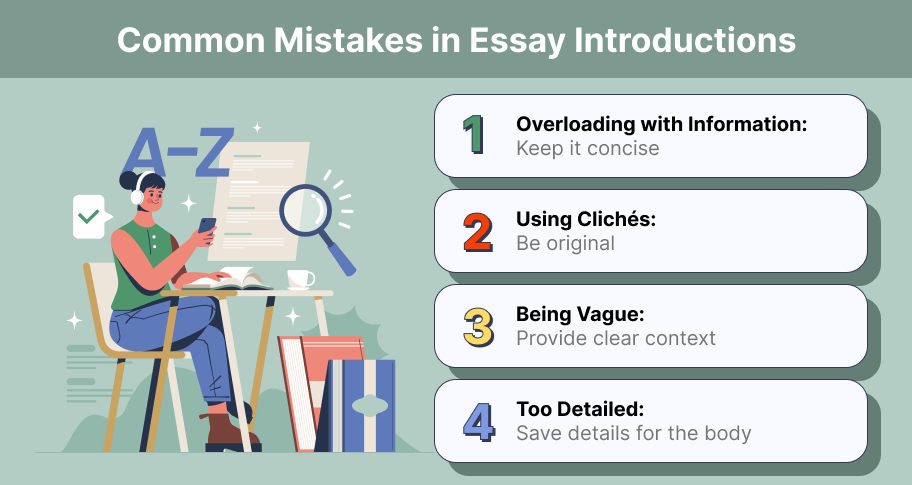

Common Mistakes to Avoid

When writing an essay introduction, it’s important to avoid certain common mistakes (these are what we call the three deadly sins of writing an introduction). Avoid them if you want a successful intro.

Overloading with Information

One of the most common mistakes is overloading the introduction with too much information. While it’s important to provide context, the introduction should not be mistaken for the body (the meat) of the essay. Be concise and focused. If something needs or deserves more explanation, reserve a section of the body for that purpose (and say so). Don’t burden your reader with too much detail up front.

Starting with Clichés

Using clichés or overused phrases in your introduction is tedious as all get out. It makes you look unpolished, unprofessional, and immature. Phrases like “Since the dawn of time…” or “In today’s modern world…” are tired and trite. Don’t use them!

Being Too Vague or Too Detailed

Striking the right balance between being too vague and too detailed is a challenge—but it’s one you have to rise up to. A vague introduction lacks direction and focus. An overly detailed introduction can lack the same things, though. Shoot for a clear and precise introduction that provides enough information to gear up the reader for the topic but leaves room for further exploration in the body of the essay.

Tips for Writing an Engaging Introduction

To write an introduction that is engaging, follow these tips:

Keeping it Concise

A good introduction is concise and to the point. Just get rid of unnecessary words or phrases that add no value to your essay. There should be no room in your essay for fluff. If the sentence adds nothing, scrap it!

Using Powerful and Relevant Language

The language you use in your introduction should be powerful and relevant to your topic. Don’t be generic: be vivid and alive, and your reader will thank you for it.

Ensuring Alignment with the Rest of the Essay

Your introduction should align with the rest of your essay in terms of tone, content, and structure. It is all one: intro, body, conclusion. They should go together like bones in a body. A well-aligned introduction starts off the logical flow of ideas throughout the rest of the essay.

How Long Should an Essay Introduction Be?

The length of an essay introduction will vary depending on the length of the essay. As a general rule, the introduction should be about 10% of the total word count. For a standard five-paragraph essay, the introduction should be one paragraph long, or a third of one double-spaced page. Longer essays may benefit from a more detailed introduction.

Can You Use Questions in Your Introduction?

Yes, using questions in your introduction can be a great way to hook your reader. Questions get people to think critically. A well-placed question can inspire curiosity and guide the reader towards your way of thinking.

How Do You Revise an Introduction?

Revising an introduction involves reviewing it for clarity and consistency. Once finished with your first draft, step away for a bit, and come back with fresh eyes. Read the whole thing and note any parts that seem lacking. Revise them to address their flaws. Re-read the whole thing again to see if it flows more smoothly now. Repeat again until perfect.

How to Start an Argumentative Essay?

To start an argumentative essay, begin with a hook that relates to some controversy related to the topic you will be arguing. You can use a relevant quote or stat, or just pose a provocative question. Toss in some background information to establish context. Then, state your thesis to articulate your position on the issue and show the main arguments that you will discuss in the essay.

How to Start Off an Essay?

Introduce the topic with a fact, a stat, a question, a statement of interest, a story, or some other tidbit that might call the reader to mind. Once you have the reader’s attention, give some background info on the topic. Follow that up with your point—i.e., your thesis statement (what you intend to show in the body of your essay).

How to Start an Essay About Yourself?

Personal essays let you talk about yourself. So, since it’s an essay about you, start off with what you’re doing or thinking as it pertains to the main point of the essay. A personal reflection, a personal anecdote, a personal struggle—all of it is fair use. From there, give some background information about yourself, and then tell the main point of your essay.

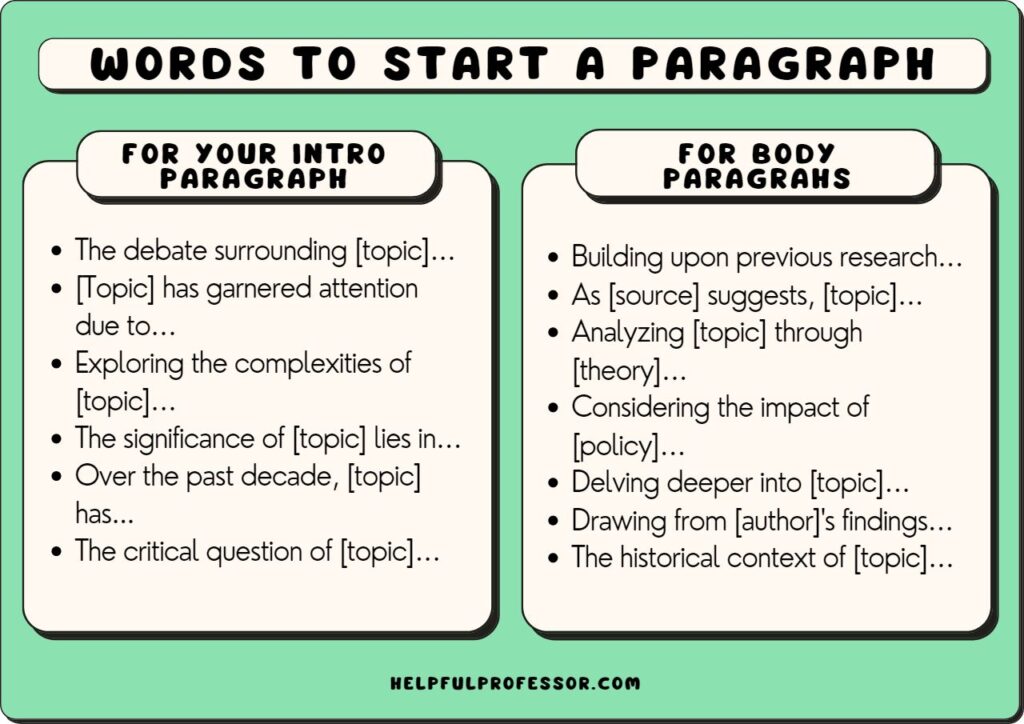

How to Start a Paragraph in an Essay?

Starting a paragraph in an essay involves introducing a new idea or point that supports your thesis. Begin with a topic sentence : this will be the main idea of the paragraph. Next, give evidence or examples to support the main idea, and link it back to the thesis of your essay. Conclude with some transition words that let the reader know what to expect in the next paragraph.

Writing an essay introduction is one of the most important things to learn. Knowing the key elements of an essay introduction, avoiding common mistakes, and following a step-by-step approach, will help students succeed more easily in their academic endeavors. Keep it clear, keep it simple, and keep it on point.

With practice and attention to detail, you will soon master the art of writing essay introductions and create essays that win over readers with ease.

If you’re looking for more tips and resources on essay writing, be sure to check out our other articles and guides [insert links here]. Happy writing!

Take the first step to becoming a better academic writer.

Writing tools.

- How to write a research proposal 2021 guide

- Guide to citing in MLA

- Guide to citing in APA format

- Chicago style citation guide

- Harvard referencing and citing guide

- How to complete an informative essay outline

AI Text Detection Services

Unlock Your Writing Potential with Our AI Essay Writing Assistant

The Negative Impacts of Artificial Intelligence on Tactile Learning

Overcome Your Writer’s Block: Essay Writing Tips for Students

How To Start An Essay (With 20 Great Examples)

Starting your essay is probably the most difficult thing to do in the whole writing process.

Facing a blank page and unsure how to start your essay? Crafting a compelling essay isn’t innate for everyone. While it’s about presenting clear ideas, even top students can struggle. For many, meeting deadlines or ensuring quality becomes daunting, leading them to consult professionals like do my essay cheap . These experts whip up top-tier essays swiftly. A standout essay can elevate your academic status, with the introduction being the pivotal hook. Many opt to hire essay writers for that impeccable start. But crafting an engaging intro is doable. Want to captivate your readers immediately? Or impress academic panels? If the task still feels daunting, there’s always the option to buy assignments online for guaranteed quality. But let’s explore ways to start an essay on your own.

How to start your essay? – The most straightforward advice

In his famous book “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft” , Stephen King said: “The scariest moment is always just before you start.” So the best thing to do is to start writing as soon as you can. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Just sit down and write anything, because the Muse comes to those who are brave enough to start. Maybe you’ll throw half of it away, but at least you’ll have something to hang on to.

How to begin your essay? – The lengthier and more appropriate advice

The aim of an academic essay is usually to persuade readers to change their minds about something. It can also be a descriptive, expository, argumentative, or narrative essay .

But regardless of the format of the essay , the introduction should still have these basic ingredients:

- Introduce the topic – let the reader know what is it about straight away.

- Put the topic in an appropriate context. Frame it, and provide some background information.

- Narrow down the focus. If your essay is too broad, you’ll lose the interest of the reader and fail to address the important issue.

- Answer an important question or make a strong statement which you’ll defend throughout the essay.

- Orientate the reader. In the beginning, you need to answer questions like who, what, when, and how. Remember that the reader probably doesn’t know all the facts that you do.

- Briefly mention the main ideas you are going to discuss in the essay.

How long should an essay introduction be?

It all depends on the overall length of your essay. If it’s a standard, five-paragraph college essay , the introduction should only take one paragraph or 60-80 words. But if you’re writing something longer, for example, a five-page interpretation of a literary work, the introduction could take two to three paragraphs or 120-150 words. You can measure the length using a simple word counter but don’t obsess too much about the number. The crucial thing is to say what you need to say and impact the reader.

The aim of the introductory paragraph

The first paragraph is always tricky because it serves a double purpose. It has to state what the essay will be about, but it needs to hook the readers and motivate them to read on. That’s why you need a perfect balance between clinical precision and artistic flair.

If you truly want to learn how to begin an essay, there are three best ways to do it:

- Read as many great essays as possible

- Write as many great essays as possible

- Check examples of great essay introductory paragraphs (that’s what you can see below)

20 Great examples and tips on how to start an essay:

1. describe a setting and start with an emotional punch.

“I’ve been to Australia twice so far, but according to my father, I’ve never actually seen it. He made this observation at the home of my cousin Joan, whom he and I visited just before Christmas last year, and it came on the heels of an equally aggressive comment.” – David Sedaris, Laugh, Kookaburra

2. Start with a deeply personal story from your childhood

“One Sunday morning when I was a boy, my father came out of his office and handed me a poem. It was about a honeybee counseling a flea to flee a doggy and see the sea. The barbiturates my father took to regulate his emotions made him insomniac, and I understood that he’d been awake most of the night, laboring over these lines, listing all the words he could think of ending in a long “e.” – Charles D’Ambrosio – Documents

3. Create a mysterious atmosphere

“Moths that fly by day are not properly to be called moths; they do not excite that pleasant sense of dark autumn nights and ivy-blossom which the commonest yellow-underwing asleep in the shadow of the curtain never fails to rouse in us.” – Virginia Woolf – Death of the Moth

4. Throw the reader straight into the middle of the events

“Earlier this summer I was walking down West End Avenue in Manhattan and remembered, with a sadness that nearly knocked me off my feet, just why I came to New York seven years ago and just why I am now about to leave.” – Meghan Daum – My Misspent Youth

5. Start with universal questions of life and death

“I know it is coming, and I do not fear it, because I believe there is nothing on the other side of death to fear. I hope to be spared as much pain as possible on the approach path. I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state.” – Roger Ebert – Go Gentle Into That Good Night

6. Start with a question and then answer it

“What is the charm of necklaces? Why would anyone put something extra around their neck and then invest it with special significance? A necklace doesn’t afford warmth in cold weather, like a scarf, or protection in combat, like chain mail; it only decorates. We might say, it borrows meaning from what it surrounds and sets off, the head with its supremely important material contents, and the face, that register of the soul.” – Emily R. Grosholz – On Necklaces

7. Start with irony

“In Moulmein, in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people – the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me.” – George Orwell – Shooting an Elephant

8. Begin by creating great expectations of what’s to come (use the introduction as bait)

“At a dinner party that will forever be green in the memory of those who attended it, somebody was complaining not just about the epic badness of the novels of Robert Ludlum but also about the badness of their titles. (You know the sort of pretentiousness: The Bourne Supremacy, The Aquitaine Progression, The Ludlum Impersonation, and so forth.) Then it happily occurred to another guest to wonder aloud what a Shakespeare play might be called if named in the Ludlum manner.” – Christopher Hitchens – Assassins of The Mind

9. Start with a puzzle (notice how you start to wonder who is she talking about in this introduction)

“The first time I heard her I didn’t hear her at all. My parents did not prepare me. (The natural thing in these situations is to blame the parents.) She was nowhere to be found on their four-foot-tall wood veneer hi-fi. Given the variety of voices you got to hear on that contraption, her absence was a little strange.” – Zadie Smith – Some Notes on Attunement

10. Start with dark humor

“When I was young, I thought Life: A User’s Manual would teach me how to live and Suicide: A User’s Manual how to die.” – Édouard Levé – When I Look at a Strawberry, I Think of a Tongue

11. Start with an unusual question that will pull the readers in

“Do you know what a twerp is? When I was in Shortridge High School in Indianapolis 65 years ago, a twerp was a guy who stuck a set of false teeth up his butt and bit the buttons off the back seats of taxicabs. (And a snarf was a guy who sniffed the seats of girls’ bicycles.)” – Kurt Vonnegut – Dispatch From A Man Without a Country

12. Commence by taking the reader into the world of mystery and awe

“The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory, magical; art was an instrument of ritual. (Cf. the paintings in the caves at Lascaux, Altamira, Niaux, La Pasiega, etc.) The earliest theory of art, that of the Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of reality.” – Susan Sontag – Against Interpretation

13. State your thesis at the very beginning – be clear about it

“Science has beauty, power, and majesty that can provide spiritual as well as practical fulfillment. But superstition and pseudoscience keep getting in the way providing easy answers, casually pressing our awe buttons, and cheapening the experience.” – Carl Sagan – Does Truth Matter – Science, Pseudoscience, and Civilization

14. Start with the obvious that’s not so obvious after all

“To do something well you have to like it. That idea is not exactly novel. We’ve got it down to four words: “Do what you love.” But it’s not enough just to tell people that. Doing what you love is complicated.” – Paul Graham – How To Do What You Love

15. Be unpredictable and highly intellectual

“Once, in a dry season, I wrote in large letters across two pages of a notebook that innocence ends when one is stripped of the delusion that one likes oneself. Although now, some years later, I marvel that a mind on the outs with itself should have nonetheless made painstaking record of its every tremor, I recall with embarrassing clarity the flavor of those particular ashes. It was a matter of misplaced self-respect.” – Joan Didion – On Self Respect

16. Get straight to the point

“The enormous, pungent, and extremely well marketed Maine Lobster Festival is held every late July in the state’s mid-coast region, meaning the western side of Penobscot Bay, the nerve stem of Maine’s lobster industry.” – David Foster Wallace – Consider The Lobster

17. Start in a deeply emotional, poetic manner

“The collie wakes me up about three times a night, summoning me from a great distance as I row my boat through a dim, complicated dream. She’s on the shoreline, barking. Wake up. She’s staring at me with her head slightly tipped to the side, long nose, gazing eyes, toenails clenched to get a purchase on the wood floor. We used to call her the face of love.” – Jo Ann Beard – The Fourth State of Matter

18. Begin by describing the place and circumstances in great detail

“Two blocks away from the Mississippi State Capitol, and on the same street with it, where our house was when I was a child growing up in Jackson, it was possible to have a little pasture behind your backyard where you could keep a Jersey cow, which we did. My mother herself milked her. A thrifty homemaker, wife, and mother of three, she also did all her cooking. And as far as I can recall, she never set foot inside a grocery store. It wasn’t necessary.” – Eudora Welty – The Little Store

19. Start by presenting an original idea (frame it in a way that the reader never considered before)

“Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent, but the tests that have to be applied to them are not, of course, the same in all cases. In Gandhi’s case the questions one feels inclined to ask are: to what extent was Gandhi moved by vanity — by the consciousness of himself as a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat and shaking empires by sheer spiritual power — and to what extent did he compromise his principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud?” – George Orwell – Reflections on Gandhi

20. Be clear-headed and approach the subject as objectively as possible

“Fantasists and zealots can be found on both sides of the debate over guns in America. On the one hand, many gun rights advocates reject even the most sensible restrictions on the sale of weapons to the public. On the other, proponents of stricter gun laws often seem unable to understand why a good person would ever want ready access to a loaded firearm. Between these two extremes, we must find grounds for a rational discussion about the problem of gun violence.” – Sam Harris – The Riddle of The Gun

Looking for an answer on how to start an essay is always tricky. You can get inspiration from many sources, but if you want to create an essay that packs a powerful punch from the very beginning, look inside yourself and come up with at least a few openings. Then, do your best to revise the opening paragraphs a couple of times so you end up with something truly impactful and attention-grabbing. Good luck! Next up, you may want to explore a guide on how to write a great 500-word essay .

Get your free PDF report: Download your guide to 80+ AI marketing tools and learn how to thrive as a marketer in the digital era.

Rafal Reyzer

Hey there, welcome to my blog! I'm a full-time entrepreneur building two companies, a digital marketer, and a content creator with 10+ years of experience. I started RafalReyzer.com to provide you with great tools and strategies you can use to become a proficient digital marketer and achieve freedom through online creativity. My site is a one-stop shop for digital marketers, and content enthusiasts who want to be independent, earn more money, and create beautiful things. Explore my journey here , and don't miss out on my AI Marketing Mastery online course.

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

How to Start a College Essay Perfectly

College Essays

If you've been sitting in front of a blank screen, unsure of exactly how to start a personal statement for college, then believe me—I feel your pain. A great college essay introduction is key to making your essay stand out, so there's a lot of pressure to get it right.

Luckily, being able to craft the perfect beginning for your admissions essay is just like many other writing skills— something you can get better at with practice and by learning from examples.