An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

LATER FIRST MARRIAGE AND MARITAL SUCCESS

Norval d glenn, jeremy uecker, robert w b love jr.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Direct correspondence to Norval Glenn at [email protected]

Issue date 2010 Sep 1.

The research reported here used measures of marital success based on both marital survival and marital quality to assess how well first marriages entered at relatively late ages fare in comparison with those entered younger. Analysis of data from five American data sets indicated that the later marriages fare very well in survival but rather poorly in quality. The greatest indicated likelihood of being in an intact marriage of the highest quality is among those who married at ages 22-25, net of the estimated effects of time since first marriage and several variables that might commonly affect age at marriage and marital outcomes. The negative relationship beyond the early to mid twenties between age at marriage and marital success is likely to be at least partially spurious, and thus it would be premature to conclude that the optimal time for first marriage for most persons is ages 22-25. However, the findings do suggest that most persons have little or nothing to gain in the way of marital success by deliberately postponing marriage beyond the mid twenties.

1. Introduction

The extensive literature on age at marriage and marital success focuses largely on differences between teen and early to middle twenties marriages and devotes little attention to marriages that begin at older ages. The main reason for this emphasis is a huge difference in survival rates between teen marriages and all others, which is only moderately reduced by controls for education, socioeconomic background, race, and so forth ( Becker, Landes, and Michael, 1977 ; Bennett, Blanc, and Bloom, 1988 ; Bumpuss and Sweet, 1972 ; Bumpuss, Martin, and Sweet, 1991 ; Greenstein, 1990 ; Heaton, 1990 ; Lehrer, 2008 ; Menken, Trussel, Stempel, and Babakel, 1991; Morgan and Rindfuss, 1985 ; Schoen, 1975 ; South, 1995 ; Teachman, 2002 ; Thornton and Rodgers, 1987 ; Waite and Lillard, 1991 ). In contrast, the relationship of age at marriage to marital outcomes beyond the mid to late twenties has been found to be relatively weak, with most studies showing a leveling off of survival or a slight increment or decrement at the older ages. Apparently the only major study that found more than a slight decrement is that reported in Becker, Landes, and Michael (1977) . Some inconsistency in results is to be expected given that until recently the number of respondents who married after their mid to late twenties was quite small in most survey samples used for the study of marital outcomes, which of course also has discouraged researchers from focusing on those who married at the older ages.

Another characteristic of most research on age at marriage and marital success is its use of marital survival, or divorce-non-divorce, as the only measure of marital success. The limitations of marital survival as the sole measure of marital success are well known, and thus we need discuss them only briefly here. Many unsatisfactory marriages (from the standpoint of the spouses) endure for various reasons, including a lack of perceived good alternatives to the current marriage, moral and religious objections to divorce, concern about the effects of divorce on children, economic dependency, and the economic costs of divorce. Arguably, when young persons marry and then quickly divorce (especially before children are born), that is a better outcome than a stable but stale, unsatisfying, or destructive marriage. If the latter outcomes are more common among persons who marry at relatively late ages, their lesser tendency to divorce is not necessarily a favorable marital outcome.

The few studies that have related age at marriage to global measures of marital quality have generally found either virtually no relationship or a weak positive one ( Bahr, Chappell, and Leigh, 1983 ; Glenn and Weaver, 1978 ; Lee, 1977 ). These findings do little to clarify the relationship between age at marriage and marital success, because the quality of intact marriages, by itself, is arguably even a poorer measure of marital success than divorce-non-divorce ( Glenn, 1990 ; 1998 ; Rockwell, 1978 ). In the population of persons in intact marriages, many of the persons who have had the least successful marriages are not present because they have divorced—a kind of sample selection bias that can produce observed relationships between variables that are smaller than, or even opposite in sign from, the causal relationships they are supposed to reflect.

Research that has not used global assessments such as happiness and satisfaction as measures of marital quality has found a positive monotonic relationship between age at first marriage and some dimensions of marital quality. For instance, Amato et al. (2007) found a monotonic decline with age at marriage of “divorce proneness,” or “thinking about divorce,” with a particularly large decrease from ages 30-34 to age 35 and older (p. 79). Although divorce proneness is a better measure of marital success than divorce itself, it suffers from the same limitations, because divorce may not be a realistic possibility for many persons in less than emotionally high quality marriages and may simply be unthinkable for others. Amato et al. (2007) report that the findings are similar for “marital interaction,” which increased with age at marriage, and “problems,” which decreased, but they do not report specific data. These findings, combined with the flat pattern of marital happiness and satisfaction with age at first marriage, suggest that many marriages of those who marry late are “good enough” ones characterized by low emotional intensity.

So far as we have been able to determine, there are no reports in the academic literature of research on the effects of age at marriage that has tried to simultaneously take into account marital stability and quality. However, two non-academic publications report the results of such attempts, and both, using different data sets, found that marital success as measured (being in a high-quality intact first marriage versus all other marital outcomes) showed a rise in success with age at marriage until the early to mid twenties and a decline thereafter (Glenn, 2005; Glenn and Marquardt, 2001). An alternative way to deal with both martial stability and quality would be to use marital quality as the dependent variable and apply a correction for selection bias resulting from divorce ( Heckman, 1979 ). However, such corrections work best when they use an instrumental variable that affects the selection but not the dependent variable, and it is hard to imagine an available variable that predicts marital survival but not marital quality. To our knowledge no one has used selection models in studying age at marriage and marital outcomes.

The steep increase in the typical age at first marriage in the United States over the past three decades (by more than five years) has increased both the feasibility and importance of studying differences in marital outcomes for persons who marry at different ages above the early twenties. In recent years about half of all first marriages of females, and well over half of all first marriages of males, have been at age 25 or older, the estimated median age at first marriage in 2005 being 27.1 for men and 25.3 for women (U. S. Census Bureau, 2006)—a condition that makes normative and typical what used to be considered late marriage. It also makes assessing the outcomes of later marriage, and understanding the reasons for those outcomes, important for practical reasons, as persons decide whether or not to participate in the trend to later marriage, and as third parties, such as parents and counselors, decide on the wisdom of encouraging later marriage. Understanding the reasons for the marital outcomes for persons who marry relatively late is also important for a general understanding of the bases for marital success.

We believe, therefore, that the time has come to focus research specifically on persons who first marry at a relatively late age and to do so in a way that takes into account both marital stability and quality. In the research reported here, we first estimated the effects of age at marriage on outcome variables designed to reflect both marital stability and quality, controlling several variables that clearly might affect both the independent and dependent variables. Then we conducted explanatory analyses designed to cast light on the reasons for the findings and to help decide, among others things, whether the estimated “effects” are causal or spurious.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

The literature provides no systematic theory to predict or explain the pattern of marital outcomes by age at first marriage, but it does provide several relevant theoretical perspectives or what perhaps might better be called theoretical fragments or lines of theoretical reasoning. We call each one a thesis.

The most commonly discussed of these seems to be the maturation thesis , or the view that marriages are more likely to succeed if the spouses have reached a high level of psychological maturity at the time of marriage, if they have had time to develop good relationship skills, and if their standards for a spouse and what they have to offer on the marriage market have stabilized ( Glenn, 2002b ; Lehrer, 2008 ; Oppenheimer, 1988 ). This view has often been used to explain why teen marriages are highly unstable, but since psychological maturation tends to continue through young adulthood and since some aspects of marital desirability, such as long-term earning ability, often remain unclear through the twenties, this thesis predicts increments, though decreasing ones, in marital success with age at marriage through the twenties and into the thirties. If, as many observers believe, psychological maturation now occurs more slowly through adolescence and young adulthood than it did a few decades ago ( Arnett, 2004 ; Cote, 2000 ), the thesis also predicts that appreciable increments in marital success with marital age have recently moved up to higher ages. For instance, the average marital success of persons who married in their thirties should have recently increased relative to that of persons who married in their late twenties.

Almost the opposite of the maturation thesis is the coordinated development thesis , which is rarely discussed by family social scientists but which seems to be fairly common among lay persons. In a rare treatment of this view by a social scientist, sociologist Mark Regnerus (2009) gets at its essence when he writes that “We learn marriage just as we learn language, and to the teachable, some lessons just come easier earlier in life….” This thesis is akin to the popular belief that persons who spend early adulthood living alone tend to become “set in their ways” and thus tend to have trouble adjusting to marriage. Another aspect of this view is the belief that couples who marry at a relatively young age are more likely than others to develop compatible live styles, values, and so forth after they marry because they are more malleable and flexible than older persons. Stated differently, the quality of the marital match is not fixed at marriage and is more likely to change positively if the persons are relatively young when they marry.

Related to the notion that persons become “set in their ways” as they experience solitary living is the proposition that experiencing a long series of low commitment relationships, most of which end badly, makes it difficult for persons to fully to commit to marriage. We call this the destructive relationship experiences thesis . This view appears fairly frequently in the social science literature and is usually derived from such empirical findings as that the number of premarital cohabitations is a negative predictor of favorable marital outcomes and that age at marriage is positively associated with number of premarital cohabitations ( Axinn and Thronton, 1992 ; Lehrer and Chiswick, 1993 ; Teachman and Polonko, 1993 ). The association of number of premarital cohabitations with divorce is almost certainly partially spurious because serial cohabitators tend to have preexisting characteristics not conducive to marital success ( Schoen, 1992 ; Bennett, Blanc, and Bloom, 1988 ), but according to the reasoning of such authors as Axinn and Thornton (1992) , it is not likely to be totally spurious.

According to another view, which we call the length of search thesis , the longer a person searches for a mate and “circulates” on the marriage market (at least to a certain point), the greater is the probability of a good marital match when he/she marries ( Becker, 1981 ; Levinger, 1965 ; South, 1995 ). This thesis posits that teenagers in particular, and persons in their early twenties to a lesser extent, typically have not met and gotten to know a large and varied enough pool of prospects to know what they want in a spouse and have not adequately tested their desirability on the mating market, leading often to marriage to an inappropriate spouse. Some authors who discuss the thesis believe that the search is often prematurely terminated, or skipped entirely, by “premature entanglement” ( Glenn, 2002b ) or by “sliding” into relationships rather than deciding to enter them ( Stanley, Rhoades, and Markman, 2006 ), for example through casual decisions to cohabit or pregnancies.

The simple version of this thesis assumes that the longer the search, the better, and thus it predicts a positive monotonic relationship between age at marriage and marital success. A more complex version takes into account that the search is likely to be productive only up to a certain length of time, beyond which the person will likely have already failed to take advantage of most of the opportunities for good matches that he/she will ever have, perhaps including the very best ones. Furthermore, according to this view, as people leave school or college and go into the world of work, opportunities to meet prospective spouses are likely to diminish, thus hampering the search for appropriate mates ( Glenn, 2002b ). A related point is that as the influence of parents, other relatives, and long-term friends diminish in young adulthood, and as gaining background information on prospective spouses becomes more difficult as persons move away from their communities and social circles of origin, bad marital choices may become more likely ( Glenn, 2002b ). This version of the thesis predicts a non-monotonic relationship between age at marriage and marital success, a positive one up to a certain age and then a negative one at higher ages.

A related view, which we call the changing marriage market thesis , is that the favorableness of marriage markets for individuals tends to change as they grow older, often improving as persons move away from the communities in which they grew up and as they circulate in wider social circles, but then deteriorating as the pool of unmarried cohort mates diminishes. The effects of this change are likely to be greater for persons with relatively little education because of their earlier typical age at marriage. The effects are also likely to be greater for women than for men because the sex ratio in a birth cohort declines as it grows older, although in the United States the ratio of unmarried men to unmarried women remains somewhat favorable to women through the thirties and into the early forties ( Glenn, 2002a ). The effects are also likely to be greater for women because of the “ticking of the biological clock,” which may lead women in their thirties and older to settle for a spouse who falls far short of their ideal ( Becker, Landes, and Michael, 1977 ). Both men and women are likely to settle for less-than-ideal spouses if they perceive that their chances for good marriages are declining. Furthermore, both men and women who first marry at a relatively late age are more likely than others entering first marriages to marry someone who has a child or children, thus creating a stepfamily with its complications ( Chiswick and Lehrer, 1990 ; Waite and Lillard, 1991 ).

Multiple predictions derive from this thesis. First, it predicts a non-monotonic relationship between age at first marriage and marital success, and, because it posits an effect of age at marriage relative to one’s cohort mates rather than an effect of absolute age, it predicts an upward movement of the turning point age between positive and negative along with the increase in the typical age at marriage. It also predicts a later age at marriage for peak marital success for sub-populations in which marriage tends to occur later, such as college graduates and men.

All perspectives discussed so far posit a causal relationship between age at marriage, or relative age at marriage, and the outcome variables. However, the relationship could be partly spurious, and perhaps largely so, due to common influences from variables other than the background variables usually controlled in the relevant research. This possibility leads to the selection thesis , according to which persons who marry at different ages tend to vary in preexisting personal characteristics that affect marital outcomes ( Bartz and Nye, 1970 ; Lee, 1977 ). For instance, there is evidence, though now dated, that low psychological adjustment is associated with early marriage ( Bartz and Nye, 1970 ), and one might speculate that before sexual gratification was readily available outside of marriage, persons who married in their teens tended to be lower in impulse control and the ability to defer gratification than persons who married at older ages. It is also possible that persons who marry at an unusually late age also tend to have characteristics inimical to marital success. For instance, those persons may be unusually particular and have unrealistically high standards for a spouse, being intent on marrying someone who conforms to their notion of an ideal spouse. In other words, they may tend to be what psychologist Barry Schwartz (2004) calls maximizers in contrast to those he calls satisficers , who are willing to settle for “good enough” rather than perfection. However, if maximizers ever marry, many if not most of them almost certainly have to settle for someone who is less than their ideal and with whom they are not highly satisfied. This could lead to a high proclivity to divorce or a high probability of being in a stable but mediocre marriage, depending on such factors as their perception of available alternatives. Or, many persons who marry late may have rather poor relationship skills or other characteristics that made it difficult for them to connect with potential spouses and that keep the quality of their marriages low when they do connect. Regardless of how their characteristics affect their marriages, persons who have trouble connecting may be disinclined to divorce and go back on the marriage market and thus are likely to be willing to settle for a “good enough” marriage. Therefore, this perspective predicts an unusually high percentage of stable but mediocre marriages among those who marry late. Furthermore, this perspective predicts that the relationship between age at marriage and marital outcomes depends on age at marriage relative to others in one’s birth cohort rather than on absolute age. Therefore, in view of the recent increase in the average age at marriage, this perspective predicts a recent increase in the age at which the age-at-marriage-marital-success relationship turns from positive to negative. It also predicts a relatively late age for the turn-around point of the up-down pattern of marital success for sub-populations in which marriage tends to occur relatively late, such as college graduates and males.

In summary, the coordinated development, destructive relationship experiences, changing marriage market, and selection theses , plus the complex form of the length of search thesis , all predict a non-monotonic relationship of age at first marriage to marital success, with the relationship being positive up to a certain age and then turning negative. In contrast, the maturation thesis and the simple form of the length of search thesis predict a positive monotonic relationship, though perhaps one that is weaker at the older ages of marriage than at the younger ones. The maturation, changing marriage market , and selection theses all predict a recent increase in the age at which the age-at-marriage relationship levels off or turns from positive to negative while the other perspectives do not. The changing marriage market thesis and the selection thesis , unlike the others, predicts a later downturn in marital success for college graduates than for those with less education and for males than for females. According to these perspectives, age at marriage relative to others in one’s birth cohort is what matters, whereas according to the other perspectives, it is absolute age that counts.

Given the inconsistency in the predictions derived from the different theoretical perspectives, we do not use the perspectives to formulate directional hypotheses. Rather, we simply ask what is the relationship between age at first marriage and measures of marital success and then perform additional analyses to help explain the findings and to tentatively assess the relative credibility of the different theoretical perspectives.

The data for the study reported here are from five different American data sets, namely, those based on the American General Social Surveys (GSS), the Oklahoma Marriage Initiative Baseline Survey (OMIBS), the Texas Healthy Marriage Initiative Baseline Survey (THMIBS), the National Fatherhood Initiative National Marriage Survey (NFINMS) and the National Fatherhood Initiative 25-State Marriage Survey (NFISMS). The GSS and the NFINMS sampled persons age 18 and older living in households in the 48 contiguous United States, the NFINMS sampled persons age 18 and older living in households in 25 states that had 73 percent of the U. S. population in 2004, while the Oklahoma and Texas surveys sampled persons age 18 and older living in households in those states. The GSS and the Oklahoma survey included only persons who could be interviewed in English whereas the other surveys included those who could be interviewed only in Spanish.

The interviews for the surveys were conducted in 2001 (OMIBS), 2004 (NFINMS and NFISMS), 2007-2008 (THMIBS), and 1973-1984 (GSS). GSS data collected after 1994 could not be used because the age at first marriage question was dropped after that date, being reinstated in 2006 but not on the same subsample questionnaire as the marital happiness question. We restricted most of the analyses with the GSS data to 1985-1994 to keep the data reasonably recent but used earlier data to help detect trends. Aside from the GSS, which used face-to-face interviews, all of the surveys were random digit dialing telephone household surveys with RDD samples obtained from Survey Sampling International, and all used the most recent birthday method to select respondents within households. The two NFI surveys and the Texas survey were conducted by the Office of Survey Research at the University of Texas at Austin and the Oklahoma survey was conducted by the Oklahoma State University Bureau of Social Research. Except for the Texas survey, all of the telephone surveys had American Association for Public Opinion Research (2008c; 2008b ) individual cooperation rates above 80 percent and AAPOR response rates in the range of 45-55 percent, which are normal for recent RDD telephone surveys with relatively short interview times ( Singer, 2006 ). The Texas survey, which had a much longer interview time (around 45 minutes) than the other surveys and was conducted later than the others and thus was more affected by the recent decline in response rates to telephone surveys, had AAPOR individual cooperation rates in the range of 61 to 77 and response rates varying from 12 to 24 for the six kinds of response rates recommended by AAPOR. We included the Texas survey in the study in spite of its low response rate for two reasons, namely, (a) recent evidence suggests that response rates bear little relationship to the accuracy of parameter estimates derived from sample data ( American Association for Public Opinion Research, 2008a ; Singer, 2006 ), and (b) the results from the Texas survey are very similar to those from the other surveys.

The NFI 25-State Marriage Survey interviewed an approximately equal number (400 to 404) of respondents from each of the states, and the data set includes a weight variable to make the data representative of the total adult population of the combined 25 states, the weights varying from .09 for South Dakota to 4.02 for California. 2 We used weighted data for our analyses.

3.2. Variables

The independent variable for the study reported here is age at first marriage entered as four of a set of five dummy variables based on the age categories of less than 20, 21-22, 22-25, 26-29, and 30 or older. 1 The dependent variables for the main analyses are constructed ones based on whether or not ever-married, not widowed persons had ever divorced, and for those who had not divorced, on responses to the following two global marital quality questions:

Taking things all together, how would you describe your marriage?

Would you say it is very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?

All in all, how satisfied are you with your marriage? Are you completely satisfied, very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied?

Each of the two constructed first marriage outcome variables consists of three categories that form a partially ordered scale and must be treated as a nominal variable in the analyses. The categories of the first variable are “divorced,” “intact very happy,” and “intact less than very happy” and of the second they are “divorced,” “intact completely satisfied,” and “intact less than completely satisfied.” Thus, the categories include all ever-married respondents except for widowed ones, for whom all needed data on the outcomes of first marriages are not available. The exclusion of widowed persons is not problematic because it corresponds with the removal through death of ever-married persons from the sampled population. That is, marriages ended by the death of either of the spouses are excluded from the analyses.

Ideally, persons who were widowed and had remarried would also be excluded, because in the case of those who had never divorced, their remarriages are erroneously treated as intact first marriages. Unfortunately, only the 1987-1994 General Social Surveys have information that allows this needed exclusion, but fortunately analyses with data from those surveys show that the respondents who need to be excluded are so few (3.5 percent of the ever-married and not currently widowed ones) that their exclusion does not make a very substantial difference in the results. For instance, when being in an intact first marriage reported to be very happy is regressed on age at first marriage entered as a continuous variable and all control variables used for this study are included in the equation, the logistic regression equation with the ever-widowed married persons included is .054 and with them excluded it is .043, both statistically significant at the .001 level on a two-tailed test. Even though this difference is moderate, we did supplementary analyses with persons who married in 1980 or later, among whom persons remarried after widowhood must have been very rare, to make sure that inclusion of remarried widowed persons did not appreciably affect any of our main findings.

The marital happiness question was asked on all of the surveys except the Texas survey, and the marital satisfaction question was asked on all of the surveys except the GSS. Therefore, data are available from four data sets for each marital outcome variable except “divorced,” which is available from all five data sets.

For the analyses that most directly address our basic research question, we collapsed each three-category outcome variable into a dichotomous one, namely, “intact very happy” versus all other first marriages and “intact completely satisfied” versus all other first marriages. For other analyses, we dichotomized the-marital outcome variables differently or excluded one of the three categories and compared the remaining two, for instance two categories of intact marriages. For some analyses we also dichotomized the intact marriages differently, into “completely or very satisfied” versus lower levels of satisfaction. We could not treat the marital happiness variable similarly, because there are too few responses—no more than two percent on any data set—in the “not too happy” category.

The most important control variable is years since first marriage, which we entered into the analyses as a set of dummy variables because this variable bears a nonlinear relationship to marital outcomes. The categories for the dummy variables are 0-2, 3-5, 6-8, 9-11, 12-14, 15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40-49, and 50 years or longer, the categories being more narrow for the earlier durations because changes in marriages are more frequent then. Other variables controlled because they might commonly affect age at marriage and marital outcomes are race, as a set of dummy variables (white, black, and other), Hispanic versus not Hispanic (except for the GSS), whether or not parents divorced before the respondent was age 16 (except for the Oklahoma survey), and respondent’s level of education as a set of dummy variables (less than high school graduation, high school graduation but no college, one to three years of college, and four or more years of college), and gender.

Additional variables used in the explanatory analyses are described below.

3.3. Basic analysis

We investigated the relationship between age at first marriage and being in an intact high quality first marriage, net of the estimated effects of the control variables, by using binary logistic regression, with “age 30 or older” the age-at-marriage reference category. To assess marital outcomes in more detail, we used multinomial logistic regression, with either “intact high quality marriage” or “divorced” the reference category. For all analyses we used listwise deletion of cases with missing data, which resulted in a total n for the combined surveys of 20,535 for analyses involving marital survival, 19,212 for those involving marital happiness, and 10,791 for those involving marital satisfaction.

To the extent possible, we did parallel analyses with data from the different data sets, and then we did simple meta-analyses, using the adding Zs method for significance tests and the weighted (for sample size) mean of the coefficients as the effect size estimate for all of the data sets considered together ( Cooper, 2004 ). In the absence of directional hypotheses, all significance tests are two-tailed. The results of the meta-analyses are in Tables 1 and 2 , and the results of the analyses with data from the different data sets are available from the senior author upon request.

Meta-analysis results: Mean (weighted by sample size) logistic regression coefficients relating age at first marriage to first marriage outcomes

Meta-analysis results: Mean (weighted by sample size) multinomial logit regression coefficients relating age at first marriage to first marriage outcomes

p < .001

The changing marriage market thesis predicts gender differences in the findings, and thus we repeated our basic analyses separately for men and women. The maturation, changing marriage market , and selection theses all predict changes in the pattern of marital outcomes by age at marriage in concert with the change in the typical age at marriage, and thus we supplemented the 1985-1994 GSS analysis with one that included data from earlier surveys. The changing marriage market thesis and the selection thesis predict differences by educational level and gender, and thus we did separate analyses for college graduates and for respondents with less education, and for males and females.

We defer description of the explanatory analyses until after the report of the basic analysis results, upon which the nature of the explanatory analyses depend.

4.1. Findings from basic analyses

The logistic regression results with “intact first marriage of any quality” versus not intact (first column of Table 1 ) show a strong positive monotonic relationship with age at first marriage, although the difference between ages 26-29 and 30 and older is not significant and thus we cannot be confident that marital survival does not level off after marriage in the late twenties. This finding is important mainly because it shows that in the only way in which this study corresponds with other recent studies that have estimated the effects of age at marriage, its findings are consistent with those from the other research. It is clear that in the United States in recent years, the later marriages as a whole have been at least as likely to survive as the moderately late ones and much more likely to do so than the earliest ones.

The logistic regression results with both “intact very happy marriage versus others” and “intact completely satisfied with marriage versus others” as dependent variables are consistent with the up-down pattern of marital success with age at first marriage predicted by several of the theoretical perspectives (second and third columns of Table 1 ). The evidence for the up-down thesis is weak in the case of the happiness variable but is quite strong in the case of the satisfaction variable, with the indicated success of the latest marriages being about as low on the average as that of the earliest ones. Overall, the findings provide considerable support for the existence of an up-down pattern, though of course marital happiness and marital satisfaction are different constructs that may relate differently to age at first marriage. In any event, the findings provide no evidence for a positive monotonic relationship of age at first marriage to marital success, and they indicate that using marital survival as the sole indicator of marital success yields highly misleading results.

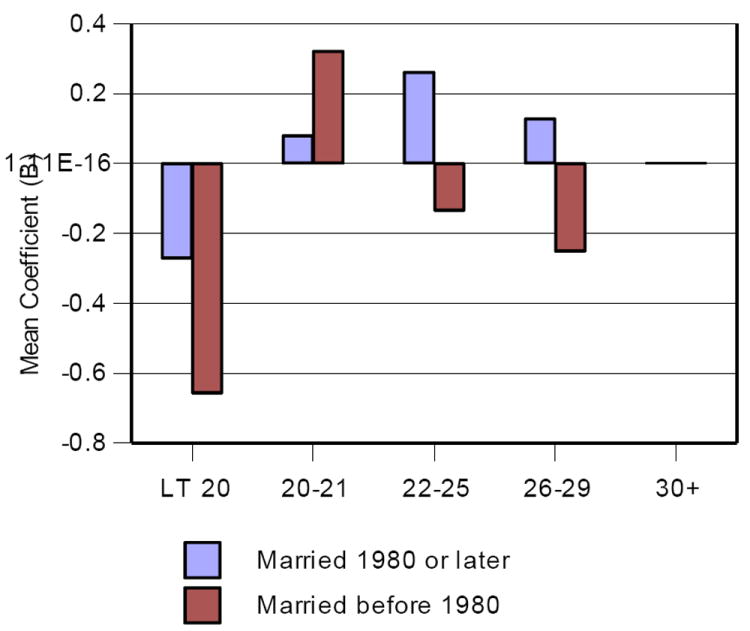

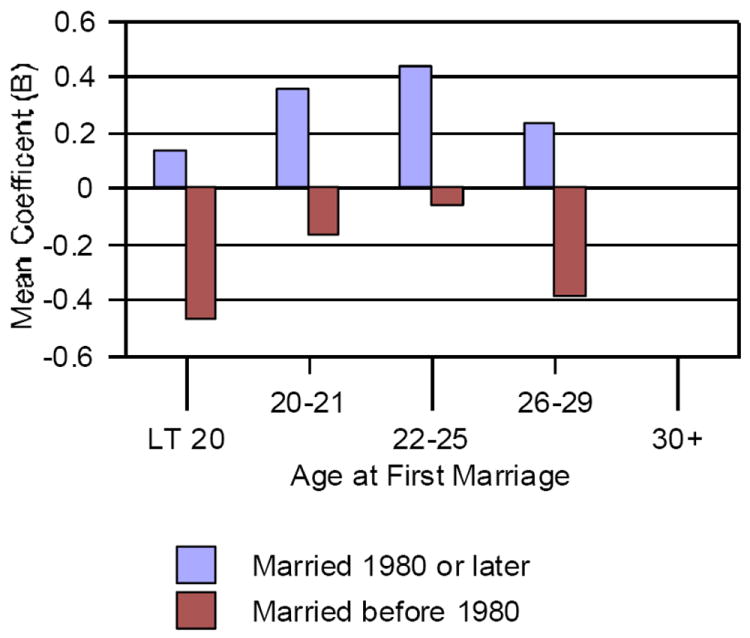

In view of the fact that the population sampled for this study includes all ever-married non-widowed persons age 18 and older, one might suspect that the findings are driven largely by the older respondents, who married prior to the increase in age at first marriage during the past few decades. It is also possible that the findings are distorted somewhat by the misclassification of some remarried widowed persons as being in intact first marriages. To investigate these possibilities, we conducted separate analyses for persons who first married before 1980, which is about when the upward trend in age at marriage began, and for those who married in 1980 and later. The results for our two main dependent variables are shown in Figures 1 and 2 .

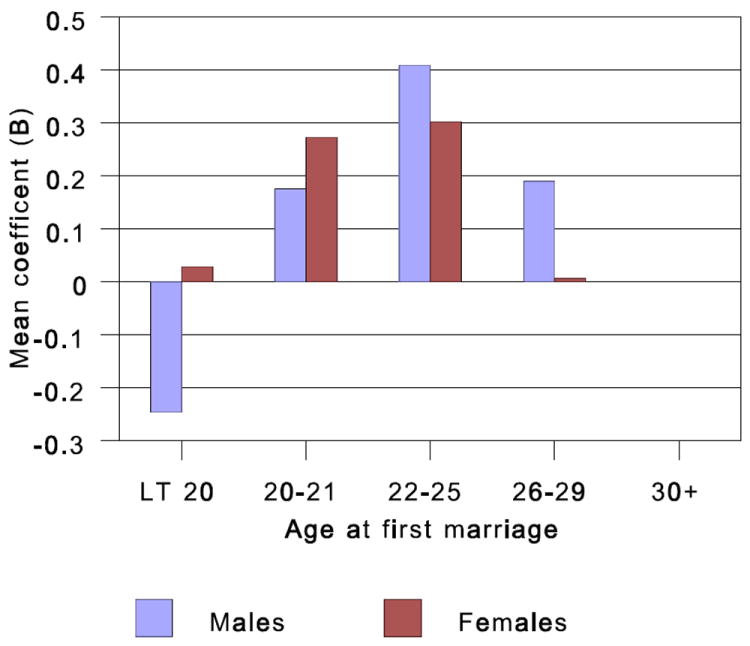

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “very happy” marriages, by age at first marriage and marriage cohort, weighted (for sample size) mean from four data sets, reference category = age 30+

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “completely satisfying” first marriages, by age at first marriage and marriage cohort, weighted (for sample size) mean from four surveys, reference category = age 30+

The principal findings of our study clearly did not result from inclusion of respondents who married before 1980, because the up-down pattern, with indicated marital success increasing up to ages 22-25 and declining after that, is more pronounced for respondents who married in 1980 or later than for all respondents. Although the mean coefficient for ages at marriage of 22-25 in the case of intact very happy marriages is only significant at the .10 level for all respondents, it is significant at the .01 level for respondents who married in 1980 or later. For respondents who married before 1980, the pattern is up-down-up, which suggests that the up-down pattern emerged or became more pronounced as the typical age at first marriage increased. There are two alternative explanations, however, namely, (a) that misclassified remarried widowed persons are distorting the data for the older respondents, and that the differences by marriage cohort are time-since-marriage (age) effects rather than period effects. That is, the up-down pattern may tend to diminish or disappear as a marriage cohort grows older.

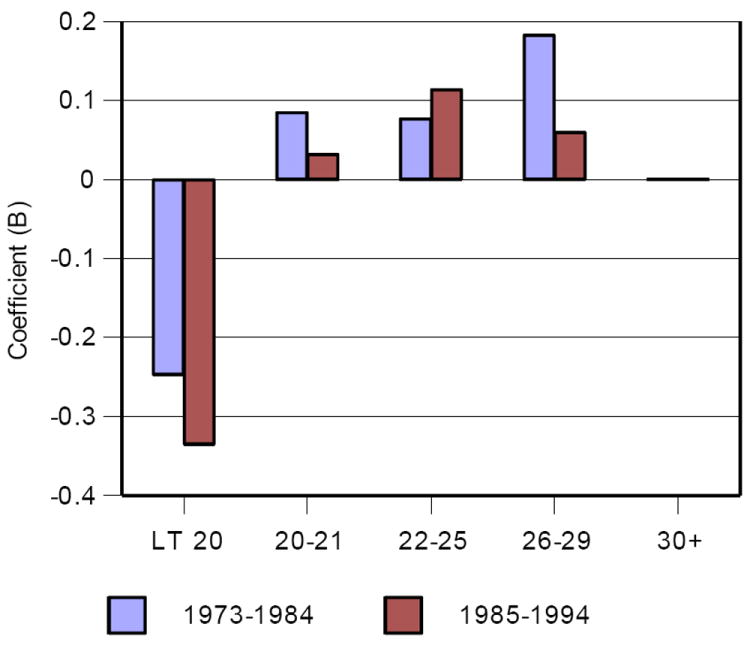

The GSS data, which come from multiple surveys, can provide limited evidence concerning this issue. We conducted separate analyses for 1973-1984 and for 1985-1994 with respondents who married no more than 20 years before the surveys were conducted, the results of which are in Figure 3 . The 1985-1994 data show the familiar up-down pattern, while the earlier data do not, though they do indicate lower marital success for ages 30 and older than for any other age category except less than 20. Contrary to expectations, the 1973-1984 data show a later peak age-at-marriage for marital success than do the 1985-1994 data. These findings are suggestive only, but they are consistent with the view that the up-down pattern has strengthened in recent decades, and they provide no evidence of an upward shift in the peak age-at-marriage for marital success as the typical age at first marriage has increased.

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “very happy” marriages, by age at first marriage, respondents who married 20 or fewer years before the surveys, 1973-1984 and 1985-1994, data from GSS

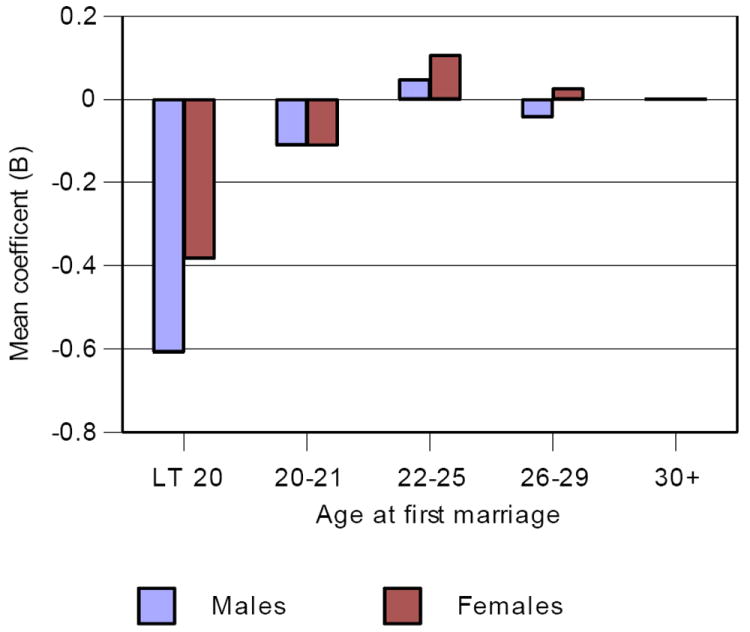

In contrast to earlier studies, this one shows a negative relationship between age at first marriage and marital quality among persons in intact first marriages (see the first three columns in Table 2 ). The adjusted (for the estimated effects of the control variables) mean coefficients shown in the table indicate how prevalent higher quality marriages were relative to lower quality ones, and thus the fact that they decrease from the early ages at marriage to the later ones indicates an association of low marital quality with high age at marriage. The data in the third column are particularly important because they indicate that even the lowest quality marriages were substantially more frequent for persons who married later than for those who married earlier.

The findings on divorce and on the quality of intact marriages mean that being in an intact marriage of less than the highest quality must bear a positive monotonic relationship with age at marriage, and the data in the fourth and fifth columns of Table 1 show that relationship to be quite strong, especially in the case of being in an intact marriage that is less than completely satisfying. That finding is not just a matter of the persons who married late being more likely to be in mediocre marriages, because the data in the last column show that being in an intact marriage of poor quality relates positively and strongly to age at marriage.

The data in the last three columns of Table 2 indicate that when people find themselves in a less than good first marriage, their propensity to divorce is related to their age at marriage, with the probability of divorce being lower for those who marry later. The data in the last column are especially revealing, because the two outcomes compared are both unequivocally negative, the category of intact marriages containing only about the 12 percent who ranked the lowest in marital satisfaction among those in intact first marriages. The constraints against divorce apparently are considerably stronger among those who marry relatively late than among those who marry earlier.

All of these findings, considered together, indicate that the positive monotonic, or almost monotonic, relationship between age at marriage and marital survival that has been found by numerous studies does not mean that the later the marriage, the greater the likelihood that it will be successful. Rather, marital success apparently increases with age at marriage only up to the early to mid twenties, with increases in marital survival beyond those ages resulting entirely from a greater tendency for persons to remain in mediocre or poor marriages.

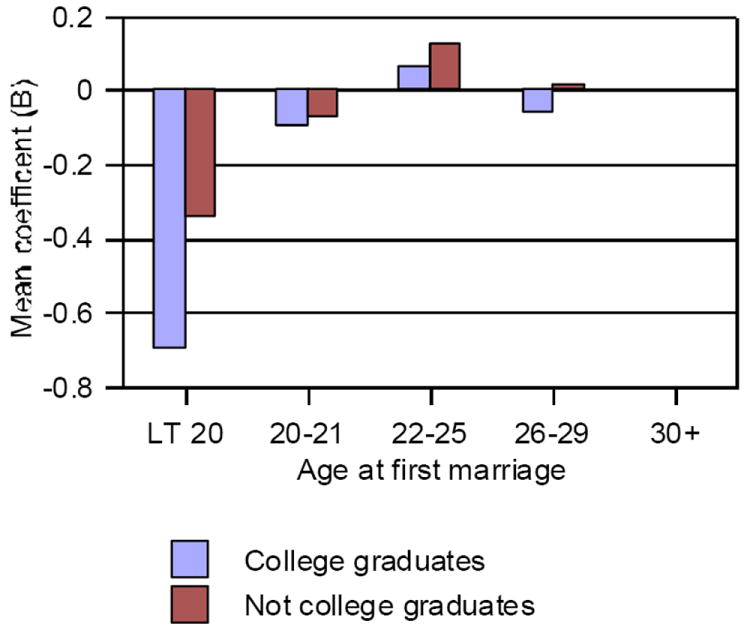

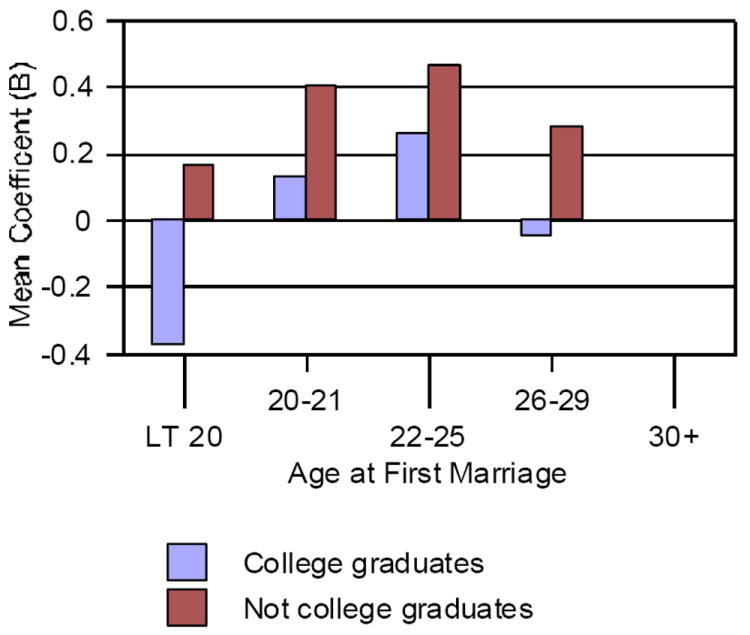

The changing marriage market thesis and the selection thesis predict relatively late peaks in marital success for subpopulations, such of college graduates and males, in which marriage tends to occur relatively late. Our findings do not show such a difference, the indicated high point in the up-down pattern of marital success being ages 22-25 for both college graduates and those with less education and for both males and females ( Figures 4 through 7 ). However, the predicted difference may be present but concealed by our use of broad age-at-first-marriage categories, and thus we can conclude only that we found no evidence for the difference and that it is unlikely to be very large.

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “very happy” first marriages, by age at first marriage and educational level, weighted (for sample size) mean coefficient from four data sets, reference category = age 30+

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “completely satisfying” first marriages, by age at first marriage and gender, weighted (for sample size) mean coefficient from four surveys, reference category = age 30+

4.2. Findings from explanatory analyses

A possible reason for the high prevalence of stable but mediocre or poor marriages among persons who marry at the later ages is that the relationship is spurious due to the common effects of attitudes toward divorce on the independent and dependent variables. An unusually strong determination to avoid divorce might lead to both extreme cautiousness about, and thus a delay in, entering into marriage and a reluctance to divorce when the marriage is found to be of less than the highest quality.

Both of the NFI surveys used for this study asked several questions about attitudes toward divorce, and four of the questions form an anti-divorce scale of moderate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .687 in the case of the NFISMS). However, when the scale scores are regressed on the age-at-marriage dummy variables and the control variables used for other analyses in our research are included in the regression equation, the relationship of age at marriage to anti-divorce attitudes is negative rather than positive. With age 30 and older used as the reference category, the unstandardized regression coefficients, from the earliest to the latest of the other categories, are .234, .221, .179, and .070, all but the last being significant. Comparable analysis of the NFINMS data yields similar results, although due to the smaller sample size no coefficient is significant.

In view of the fact that the up-down pattern is very distinct for the younger marriage cohorts, one might expect that cohabitation in some way helps account for the pattern in those cohorts. It is well established that in the United States marital quality on the average declines fairly steeply during the first few years (see various chapters in Bradbury, 1998 , for much of the evidence), and this decline may begin before marriage in the case of those who cohabit for long periods before marriage. If so, and if persons who marry later tend to have longer periods of premarital cohabitation than those who marry younger, this could account for at least some of the decline in marital success after ages 22-25.

The NFI surveys both provide information on premarital cohabitation, and it is true that cohabitation with the spouse of more than a year is negatively associated with marital success and that persons who married later were more likely to have cohabited with the spouse for more than a year. However, these relationships are only moderately strong, and thus including “cohabited with spouse for more than a year versus all others” in the regression equation does not make a substantial difference when our marital success measures are the dependent variables. For instance, with the NFISMS data and with being in a very happy intact first marriage the dependent variable, adding the cohabitation control variable lowers the coefficient for ages 22-25 only from .078 to .066. When being in a completely satisfying intact first marriage is the dependent variable, the comparable change is only from .324 to .314. In the data from the NFINMS, the comparable changes are from .927 to .921 for the variable based on marital happiness and from .720 to .706 for the one based on marital satisfaction. Therefore, variation in premarital cohabitation across the age-at-marriage categories accounts for only a small proportion of the indicated difference in marital success between the 22-25 and the 30+ categories.

Another possibility, which is discussed above in regard to the selection thesis , is that persons who marry later tend to have personality characteristics that affect both their age at marriage and their marital success. One possibility we mentioned is a tendency to be a maximizer rather than a satisficer ( Schwartz, 2004 ), that is, to always seek the very best and be reluctant to accept anything less. The fact that the relationships among variables found by this study apparently have changed little as the typical age at marriage has increased casts some doubt on this explanation because if the relationships were totally spurious, the age at which the down side of the up-down pattern of marital success begins should have increased. However, due to the small samples sizes and our use of rather broad age categories, we cannot pinpoint the exact age of the downturn, and thus the spuriousness explanation is not ruled out.

The Texas survey gathered limited information about the personalities of its respondents, and thus we were able to conduct some crude tests to estimate whether the measured relationships between age at first marriage and marital outcomes are partially spurious due to the effects of personality. The survey has a four-item maximization scale, but that has low reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .409), and only one of its items predicts marital outcomes. However, that one—a four-point agree-disagree item worded, “No matter how satisfied I am, I’m always on the lookout for something better“—has face validity as a global measure of maximization, and thus we used it as an indicator of that construct. The test for spuriousness using this variable is quite crude because of (a) the limitations of self-report personality measures, especially one-item ones, and (b) the fact that the personality characteristic was measured after—in some cases by many years—some of the marital outcomes occurred. The latter is probably the less serious limitation, given considerable evidence that personality tends to be fairly stable in adulthood (see Roberts and Del Vecchio, 2000 , for a review).

Maximizing as measured both predicts negative marital outcomes and relates positively to age at first marriage, and thus adding it to the regression equation makes a difference, albeit a small one. The age 22-25 coefficient, which compares marital success in that category with that in the age 30+ category and is the largest coefficient for the age-at-marriage categories, is reduced from .498 to .449, a change of about ten percent that is not statistically significant. Of course, use of a larger number of well measured personality variables would probably make a greater difference, possibly a substantial one, but this study provides scant evidence of spuriousness in the relationship of age at marriage to marital outcomes due to common influences from personality.

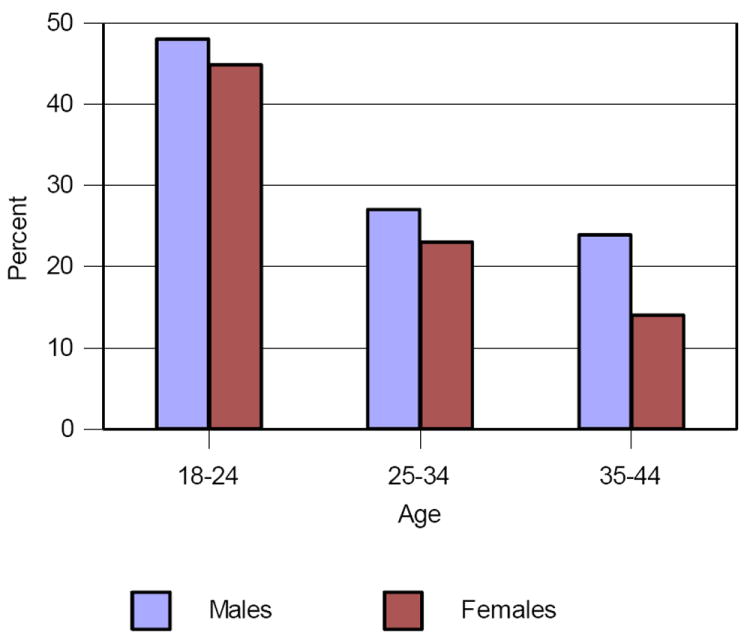

Late marriage is no doubt to some degree selective of persons who lack characteristics conducive to success on the marriage market, and persons who do have those characteristics but postpone the search for a spouse until relatively late may find that market conditions hamper their quest for a suitable match, as we point out above. Whatever the reasons may be, data from the NFISMS indicate that many persons older than the mid twenties who were “on the market” did not view their prospects as being especially good (see Figure 8 )—a condition likely to be conducive to “settling” for a spouse who falls short of one’s ideal. Unfortunately, there is no way to distinguish between respondents who lacked optimism largely because of past failures due to their personal limitations and those whose pessimism grew mainly out of market conditions external to themselves.

Percent of persons actively seeking a spouse who said their prospects were “very good,” by age and gender, NFISMS, 2005

5. Discussion

5.1. theoretical and conceptual implications.

The analysis results are clearly inconsistent with two of the theoretical perspectives discussed above, namely, the maturation thesis and the simple version of the length of search thesis , both of which predict a positive monotonic relationship of age at first marriage with marital success. Apparently, psychological maturation beyond the mid-twenties either matters little or else its positive effects on marital success are offset by other influences. Similarly, length of search apparently has substantial positive effects for most people only up to a certain point before the effects become negligible or completely offset.

We found no evidence that the age at marriage at which negative effects on marital success equal and then surpass positive ones has shifted upward in tandem with the increase in the average age at marriage. Given the width of the age-at-marriage categories we used and other limitations of our methods for assessing change, some such change may have occurred, but it is very unlikely to have been proportional to the increase in the age at marriage. The lack of evidence that the turn-around point of the up-down pattern of marital success has shifted upward, and the fact that that point seems to differ little by education or between males and females, suggests that it is absolute age that matters rather than the age at which one marries relative to when one’s cohort mates do so. This tentative conclusion is consistent with the coordinated development thesis , the complex form of the length of search thesis , and the destructive relationship experiences thesis and casts some doubt on the changing marriage market thesis and the selection thesis . However, the latter two are by no means disproven, and the fact that among persons on the marriage market those ages 25-34 seem to have distinctly less optimism about their prospects than the younger ones suggests that many persons who marry relatively late “settle” for a spouse who falls considerably short of their ideal. If this thesis is correct, the “settling” could be the result of changing marriage market conditions for persons who deliberately postpone marriage, in which case it would be a matter of age at marriage affecting marital outcomes. Or, it could be a matter of personal characteristics commonly affecting age at marriage and marital outcomes, thus creating a spurious relationship between those two variables.

In brief, it is unclear to what extent the downside of the up-down pattern of measured marital success with age at marriage is a causal relationship and the extent to which the association of later age at marriage with rather low marital success is spurious. We suspect that it is both to a substantial extent.

Perhaps as important as the substance of the findings of this study is the fact that they dramatically illustrate the limitations of using either marital survival or the quality of intact marriages as the sole measure of marital success. According to the first measure, age at first marriage bears a strong positive monotonic relationship to marital success, whereas by the second one (when a global marital quality measure is used), the relationship is negative and monotonic. When both marital survival and quality are taken into account, the relationship is non-monotonic, with the indicated success rising steeply up to ages 22-25 and declining thereafter.

Although we believe that it is very important to conceive of marital success in terms of both marital survival and marital quality, we do not argue that our implicit definition of marital quality is the only useful one. For the research reported here we used a hedonic conception of marital success, that is, the view that a good marriage is one from which the spouses derive positive emotions. This view of marital quality seems to be the prevailing one in American society and throughout the modern world, but there are alternative ones. For instance, marital quality could be defined in terms of effects on the well-being and socialization of children, or even in terms of effects on the community or the society as a whole. One could make a very strong argument for at least including effects on children in the definition, but to our knowledge no social scientist has successfully operationalized marital quality defined that way.

However, many social scientists have operationalized marital quality in a manner that is not totally consistent with a hedonic definition. For instance, multidimensional marital adjustment scales usually incorporate such variables as degree of conflict, extent of shared activities, and frequency of sexual intercourse as constituents of the construct measured, thus implicitly judging some characteristics and behaviors to be good or bad independent of their effects on the emotions and well-being of the spouses ( Glenn, 1990 , Amato et al., 2007 ).

The results of the study reported here have no direct implications for understanding marital success when marital quality is not defined in a strictly hedonic way, and thus our findings should not be considered either consistent or inconsistent with findings, such as those reported by Amato et al. (2007) and summarized above, from research that used different implicit definitions of marital quality.

5.2. Practical implications

The peaking of marital success, as measured, at first marriage ages of 22-25 has important practical implications because it is inconsistent with the widespread current belief that it is wise to wait until the late twenties or later to marry. However, that finding should be interpreted with caution, and it would be premature to label 22-25 as the optimal ages for marriage. Some of the relationship of age at marriage to marital outcomes is almost certainly spurious, which means that at least some of the persons who married relatively late would not have had better marriages if they had married earlier. Furthermore, it is likely that the optimal age at marriage varies widely among individuals and may be atypical for some categories of persons not examined separately in our research. For instance, although the optimal age suggested by our findings does not differ between college graduates and persons with less education, it might be different for persons with advanced degrees. Or it might be atypical for persons in religious subcultures that value early marriage.

The findings of this study do indicate that for most persons, little or nothing in the way of marital success is likely to be gained by deliberately delaying marriage beyond the mid twenties. For instance, a 25 year old person who meets an excellent marriage prospect would be ill-advised to pass up that opportunity only because he/she feels not yet at the ideal age for marriage. Furthermore, delaying marriage beyond the mid twenties will lead to the loss during a portion of young adulthood of any emotional and health benefits that a good marriage would bring ( Waite and Gallagher, 2000 ). On the other hand, it is extremely important to stress that the findings of this study should not lead anyone of any age to panic and thus make a bad choice of a spouse.

5.3 Needed additional research

Much is left to be done to explain the findings reported in this paper. We found strong negative evidence for two theses about how age at marriage beyond the early twenties affects marital outcomes but only tentative evidence about four other perspectives we discuss. Additional evidence could be provided by analysis of available survey data on the characteristics of persons who marry at various ages and of course by surveys designed specifically to investigate the topic. However, the most valuable evidence would probably be from in-depth interviews of persons who married at various ages and with persons of various ages who are “on the market” for a spouse.

Although we prefer to use a hedonic definition of marital quality, research on how age at marriage relates to any and all of the many variables used in multi-dimensional marital adjustment and marital quality scales is very useful, both to those who think of such variables as contributors to marital quality and to those who think of them as constituents of that concept. It is not possible to fully understand why persons who marry relatively late tend not to give their marriages the highest happiness and satisfaction ratings without studying the variables that affect marital happiness and marital satisfaction. Since age-at-marriage research using non-hedonic outcome variables has been very limited, the needed research is very extensive. For instance, it would be useful to test our speculation earlier in this paper that many marriages entered into at a relatively late age are “good enough” ones of low emotional intensity, that is, marriages low in conflict and disagreements, high in utilitarian benefits, but not reported by the spouses to be “very happy” or “completely satisfying.”

It would also be useful to expand the research on age at marriage and marital outcomes to include second and subsequent marriages as well as first ones, asking for instance if remarriages occurring as early as the mid twenties tend to equal first marriages entered into at that age. One might also ask how age at first marriage relates to eventual marital success in the case of first marriages that end in divorce, testing hypotheses about selectivity into very early marriages and the long-term consequences of very early marriages that quickly end in divorce. And there is a need for more knowledge about the outcomes of marriages that begin in middle age or later, whether they be first marriages or remarriages.

In short, in spite of the great amount of evidence about the survival of very early marriages and the results of our efforts to expand age-at-marriage research to older ages and beyond marital survival, there remains an abundance of largely unexplored research topics relating to age at marriage and marital outcomes.

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “completely satisfying” first marriages, by age at first marriage and Educational level, weighted (for sample size) mean from four surveys, reference category = age 30+

Adjusted (for estimated effects of control variables) level of ever-married nonwidowed respondents in intact “very happy” first marriages, by age at first marriage and gender, weighted (for sample size) mean coefficient from four surveys, reference category = age 30+

Only the NFISMS has enough respondents who first married at age 30 or older to make fine distinctions within that broad category. The data from that survey show no statistically significant relationships within that category of age at marriage with any of our outcome variables, with or without the control variables held constant.

The states are Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Presented at the 2009 Annual Meetings of the American Sociological Association, San Francisco, August 10

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Amato PR, Booth A, Johnson DR, Rogers SJ. Alone Together: How Marriage in America is Changing. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Do Response Rates Matter? 2008a http://www.aapor.org .

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Response Rate Calculator. 2008b http://www.aapor.org .

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions. 2000c http://www.aapor.org .

- Arnett J. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens through the Twenties. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Axinn WG, Thornton A. The relationship between cohabitation and divorce: Selectivity or causal influence. Demography. 1992;29:357–374. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bahr SJ, Chappell CB, Leigh GK. Age at marriage, role enactment, role consensus, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1983;45:795–803. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bartz KW, Nye IN. Early marriage: A propositional formulation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1970;32:258–268. [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker GS. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1981. [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker GS, Landes EM, Michael RT. An economic analysis of marital instability. Journal of Political Economy. 1977;85:1141–1187. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bennett NG, Blanc AK, Bloom DE. Commitment and the modern union: Assessing the link between premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability. American Sociological Review. 1988;53:127–138. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradbury TN, editor. The Developmental Course of Marital Dysfunction. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bumpuss LL, Sweet JA. Differentials in marital instability: 1970. American Sociological Review. 1972;37:754–766. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bumpuss LL, Martin TC, Sweet JA. The impact of family background and early marital factors on marital disruption. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12:22–42. doi: 10.1177/019251391012001003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chiswick CU, Lehrer EL. On marriage-specific capital: Its role as a determinant of remarriage. Journal of Population Economics. 1990;3:193–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00163075. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper HM. Meta-analysis. In: Lewis-Beck MS, Bryman A, Liao TF, editors. The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. pp. 635–639. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cote J. Arrested Adulthood: The Changing Nature of Maturity and Identity. New York University Press; New York: 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glenn ND. Quantitative research on marital quality in the 1980s: A critical review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:818–831. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glenn ND. Problems and prospects in longitudinal research on marriage: A sociologist’s perspective. In: Bradbury TN, editor. The Developmental Course of Marital Dysfunction. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1998. pp. 427–440. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glenn ND. Marriage and remarriage. In: Eckardt DJ, editor. Encyclopedia of Aging. Macmillan Reference USA; New York: 2002a. pp. 872–875. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glenn ND. A plea for greater concern about the quality of marital matching. In: Hawkins A, Wardle L, Coolidge D, editors. Revitalizing the Institution of Marriage for the Twenty-First Century. Praeger Publishers; Westport, CT: 2002b. pp. 45–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- Glenn ND, Weaver C. A multivariate, multisurvey study of marital happiness. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1978;40:269–282. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenstein TN. Marital disruption and the employment of married women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:657–676. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heaton TB. Marital stability throughout the child-rearing years. Demography. 1990;27:55–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heckman JJ. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometica. 1979;47:153–161. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee GR. Age at marriage and marital satisfaction: A multivariate analysis with implications for marital stability. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1977;39:493–504. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer EL. Age at marriage and marital instability: Revisiting the Becker-Landes-Michael hypothesis. Journal of Population Economics. 2008;31:463–484. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrer EL, Chiswick CU. Religion as a determinant of marital stability. Demography. 1993;30:385–404. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levinger G. Marital cohesiveness and dissolution: An integrative review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1965;27:19–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Menken J, Trussel J, Stempel D, Babakel Proportional hazards life table models: An illustrative analysis of socio-economic influences on marriage dissolution in the United States. Demography. 1981;18:181–200. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan SP, Rindfuss RR. Marital disruption: Structural and temporal dimensions. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;90:1055, 1077. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:563–591. [ Google Scholar ]

- Regnerus M. Say yes. What are you waiting for? Washington Post; 2009. Apr 26, [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts BW, Del Vecchio WF. The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;81:670–683. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rockwell R. Age at marriage and marital satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1978;40:213–217. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schoen R. California divorce rates by age at first marriage and duration of first marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1975;37:548–555. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schoen R. First unions and the stability of first marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:281–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Singer E, editor. Special issue on nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:639–810. [ Google Scholar ]

- South SJ. Do you need to shop around? Age at marriage, spousal alternatives, and marital dissolution. Journal of Family Issues. 1995;16:432–449. doi: 10.1177/019251395016004002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwartz B. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. HarperCollins Publishers; New York: 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stanley MS, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ. Sliding versus deciding: Inertia and the premarital cohabitation effect. Family Relations. 2006;55:499–509. [ Google Scholar ]

- Teachman JD. Stability across cohorts in divorce risk factors. Demography. 2002;39:331–351. doi: 10.1353/dem.2002.0019. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Teachman JD, Polonko KA. Cohabitation and marital stability in the United States. Social Forces. 1993;69:207–220. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thornton A, Rodgers W. The influence of individual and historical time on marital dissolution. Demography. 1987;24:1–22. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- U. S. Census Bureau. http:www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms2.pdf .

- Waite LJ, Gallagher M. The Case for Marriage: Why Married People Are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite LJ, Lillard LA. Children and marital disruption. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96:930–953. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (510.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections