An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Cognitive Distortions and Deficits Model of Suicide Ideation

Laura l fazakas-dehoog, katerina rnic, david j a dozois.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Department of Psychology, The University of Western Ontario, 313E Westminster Hall, London Ontario N6A3K7; Tel: 519-661-2111 x.84678; Fax: 519-850-2554. [email protected]

Received 2016 Jul 7; Accepted 2017 Jan 21; Collection date 2017 May.

Although cognitive distortions and deficits are known risk factors for the development and escalation of suicide ideation and behaviour, no empirical work has examined how these variables interact to predict suicide ideation. The current study proposes an integrative model of cognitive distortions (hopelessness and negative evaluations of self and future) and deficits (problem solving deficits, problem solving avoidance, and cognitive rigidity). To test the integrity of this model, a sample of 397 undergraduate students completed measures of deficits, distortions, and current suicide ideation. A structural equation model demonstrated excellent fit, and findings indicated that only distortions have a direct effect on suicidal thinking, whereas cognitive deficits may exert their effects on suicide ideation via their reciprocal relation with distortions. Findings underscore the importance of both cognitive distortions and deficits for understanding suicidality, which may have implications for preventative efforts and treatment.

Keywords: cognitive distortions, cognitive deficits, suicide, suicide ideation, hopelessness

Suicide is a major public health concern in North America, where it is the 9 th leading cause of death in Canada, 10 th in the United States, and the 2 nd leading cause among college and university students. Information obtained from the Statistics Canada mortality database ( Statistics Canada, n.d. ) indicates that 3,951 and 3,728 suicidal deaths were reported in Canada for 2010 and 2011, respectively. In 2007, the suicide rate was approximately 35,000 in the United States, where suicide accounts for 1.5% of all mortality ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013 ). Many of these deaths are potentially preventable with appropriate identification and intervention, highlighting the need for research that better delineates the etiology and escalation of suicidal thinking and behaviour.

University students are a population that is particularly vulnerable to mental health problems and suicidality ( Garlow et al., 2008 ). Most undergraduate students are in their late teens or early twenties, which is not only a major transitional period, but is when first episodes of many psychological disorders (e.g., depression) are most likely to appear. A survey of over 30,000 students from 34 colleges and universities in Canada found that 89% of students feel overwhelmed, 54% are hopeless, 64% are lonely, 87% report feeling exhausted, 56% experience overwhelming anxiety, and 10% had seriously considered suicide ( American College Health Association, 2013 ). Reasons for elevated risk of mental health and suicidal thinking and behaviour in students include the stress of moving, academic demands, financial and social pressures, parents’ expectations, a highly competitive job market, and an inability to “unplug” and relax.

Despite the large body of empirical research that has been devoted to identifying the risk factors associated with suicidality across university students and other populations, the majority of research has examined isolated risk factors, which on their own have limited utility for understanding and predicting suicidal behaviour. Nonetheless, several cognitive vulnerabilities, including a number of deficits (e.g., Becker-Weidman, Jacobs, Reinecke, Silva, & March, 2010 ; Linda, Marroquín, & Miranda, 2012 ; Richard-Devantoy, Szanto, Butters, Kalkus, & Dombrovski, 2015 ) and distortions (e.g., Jager-Hyman et al., 2014 ; Lakey, Hirsch, Nelson, & Nsamenang, 2014 ; McMillan, Gilbody, Beresford, & Neilly, 2007 ), have emerged as possible mechanisms that may underlie the development and maintenance of suicidal thinking and behaviour. Cognitive deficits “refer to a lack of certain forms of thinking (e.g., the absence of information processing where it would be beneficial)” ( Kendall & Dobson, 1993 , p. 10). In contrast, distortions “refer to active, but dysfunctional thinking processes” ( Kendall & Dobson, 1993 , p. 10; e.g., thoughts that are biased, contain logical errors, and are not well supported by evidence). Internalizing disorders, such as depression, are associated primarily with cognitive distortions ( Ackerman, & DeRubeis, 1993 ), whereas externalizing disorders are associated with both cognitive distortions and pronounced cognitive deficits ( Crick & Dodge, 1994 ; Milich & Dodge, 1984 ). These share bidirectional associations (e.g., distorted interpretations of stimuli [distortions] are in part a function of information processing deficits in selective attention [deficits], and the process of accessing possible responses to stimuli [deficits] is influenced by earlier occurring attributions about the stimuli [distortions; Dodge & Crick, 1990 ]), although a paucity of research has examined their reciprocal relations. The primary goal of this study was to test the components of an integrated cognitive model of suicide ideation which may have utility for understanding and predicting suicidal thinking and behavior.

Despite a paucity of research examining both cognitive deficits and distortions, researchers have found a number of negatively skewed or distorted cognitions that are associated with an increased risk of suicide ideation and attempts. Suicide ideation is defined as “any self-reported thoughts of engaging in suicide-related behavior” ( O’Carroll et al., 1996 , p. 247), whereas a suicide attempt is a “potentially self-injurious behavior with a nonfatal outcome, for which there is evidence (either explicit or implicit) that the person intended at some (nonzero) level to kill himself/herself” ( O’Carroll et al., 1996 , p. 247). Suicidal thoughts and behaviour can vary by the degree of suicidal intent, that is, the “individual’s desire to bring about his or her own death” ( Hasley et al., 2008 , p. 577). Increasingly distorted cognitions have been associated with increased severity of suicidality, and may have utility for differentiating among non-ideators, ideators, and attempters ( Beck, Steer, Kovacs, & Garrison, 1985 ). Compared to non-suicidal groups, suicidal individuals have a tendency to view their future (i.e., hopelessness), themselves, and their world, more negatively (e.g., Jager-Hyman et al., 2014 ; Miller & Esposito-Smythers, 2013 ). Hopelessness is a distortion corresponding to an overly pessimistic view of the future, and appears to have high specificity for depression, with past research indicating no association with other internalizing (i.e., anxiety) or externalizing pathology ( Alloy et al., 2012 ). Researchers have consistently found a positive correlation between levels of hopelessness and degree of suicide risk, with higher levels of hopelessness associated with increasing levels of suicide intent and completion ( Boergers, Spirito, & Donaldson, 1998 ; Kumar & Steer, 1995 ) even when controlling for the effects of depression (e.g., Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1993 ). Hopelessness is a robust predictor for eventual suicide in clinical and nonclinical samples with follow-ups as long as 13 years (e.g., Beck, Brown, & Steer, 1989 ; Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974 ; Kuo, Gallo, & Eaton, 2004 ). Furthermore, suicidal individuals evinced a cognitive distortion related to death, rating it as more positive than did their non-suicidal counterparts ( Gothelf et al., 1998 ; Neuringer, 1979 ; Orbach et al., 2007 ).

Several other cognitive factors that are associated with suicidal thinking are marked by an absence of an adaptive form of thinking, and therefore represent cognitive deficits. Schotte and Clum (1987) reported that an increased risk of suicide ideation is associated with marked problem-solving deficits in both impersonal and interpersonal domains, including the generation of significantly fewer potential alternatives and more irrelevant solutions to problems. Further, relative to non-ideating controls, individuals with suicide ideation are less likely to implement viable solutions ( Schotte & Clum, 1987 ). Similar findings have been reported in individuals who have attempted suicide as compared to non-suicidal psychiatric controls ( Pollock & Williams, 2004 ). Problem solving deficiencies are also conceptualized as avoidance of and passivity toward solving problems, and research has found that suicide ideators and attempters demonstrate greater problem solving avoidance relative to nonsuicidal psychiatric controls ( Linehan, Camper, Chiles, Strosahl, & Shearin, 1987 ; Orbach, Bar-Joseph, & Dror, 1990 ). In addition, compared to non-ideating controls, individuals who contemplate suicide demonstrate a higher level of cognitive rigidity, defined as low cognitive flexibility ( Litinsky & Haslam, 1998 ; Marzuk, Hartwell, Leon, & Portera, 2005 ; Upmanyu, Narula, & Moein, 1996 ).

It is possible that, like cognitive distortions, these cognitive deficits have utility for differentiating individuals at each stage of the suicide continuum. However, research investigating this relationship has been limited, and results have been mixed. For example, there is some evidence that relative to non-ideators, suicide ideators have deficits in problem-solving ( Schotte & Clum, 1987 ), whereas another study reported that problem-solving deficits do not differ appreciably between suicide ideators and non-ideators ( Yang & Clum, 1994 ). These mixed findings are somewhat difficult to interpret. One possibility is that the samples in these studies differed significantly in terms of the degree of suicide ideation. However, as these authors did not report on the level of suicide ideation in their respective studies, it is unclear whether these mixed results can be attributed to sample characteristics. Consistent with the observation that cognitive deficits are typically more closely associated with externalizing disorders, which are characterized by acting out, in the current study it is hypothesized that cognitive deficits will be less predictive of ideation and will vary less among suicide ideators and non-ideators than will cognitive distortions. When considered together, findings indicate that both cognitive deficits and cognitive distortions play a role in the development of suicidal thinking and behaviour, and that university students are a relevant population for examining these associations. As researchers have not proposed or studied this relationship, the degree to which deficits and distortions interact, or uniquely contribute, to suicidal thinking has yet to be examined. The primary goal of this study was to test a model of suicidal ideation in a sample of suicide ideators and non-ideators. Given that suicidal ideation and behavior are common in university student populations ( Garlow et al., 2008 ), the integrity of the proposed model was assessed utilizing structural equation modeling in a large undergraduate sample. Predictors for cognitive distortions and deficits, each represented as latent variables in the model, were selected based on research findings in the suicidology literature reviewed above. The cognitive distortions factor in the model was defined in terms of hopelessness, as well as the individual’s cognitive appraisals about self and future. The cognitive deficits factor in the model was assessed by each individual’s problem-solving deficits, approach to problem-solving (active approach versus avoidance), and cognitive rigidity (i.e., a deficit in cognitive flexibility). Further, the individual’s degree of suicide ideation was utilized as the outcome variable in the model.

Cognitive distortions and deficits are expected to have a direct association with suicide ideation. Further, cognitive distortions are expected to have a stronger relationship with suicide ideation than are cognitive deficits. It is also hypothesized that cognitive deficits and cognitive distortions will demonstrate reciprocal relations, such that increases in one will be associated with increases in the other. That is, deficits in problem solving, cognitive rigidity, and problem-solving avoidance are expected to be, in part, a function of greater hopelessness and negative appraisals about self and future, due to negative thought content interfering with effective cognitive processing ( Dodge & Crick, 1990 ). Similarly, distorted cognitions are likely related to cognitive deficits; the individual is unable to effectively manage problems, and therefore thought content has become increasingly negative over time. The proposed relationships in the model were examined by assessing whether significant differences were evident along the continuum between non-ideation and high levels of ideation.

Participants

Given the characteristics and number of parameters to be estimated in the proposed model, a sample of at least 350 participants was required to assess the fit of the model. Given that university students are considered to be an important vulnerable population, a sample of undergraduate students was recruited for the study. Three hundred and ninety-seven undergraduate psychology students enrolled in an introductory psychology course participated in the study. The age of the participants (83 males and 314 females) ranged from 17 to 43 with a mean age of 18.69 years. Of the sample, 98.7% had never been married and 94.2% were full time students. The demographic information for this sample is presented in Table 1 .

Table 1. Participant Demographic Characteristics.

Demographic information.

Prior to completing the package of questionnaires, each participant completed a demographic information sheet. Participants also provided information about their mental health history and treatment.

Suicide Ideation

The Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS; Beck & Steer, 1993 ) was used to identify individuals who had been contemplating or thinking about suicide over the previous week, and to determine their level of suicidal ideation and intent. The first 19 items of the BSS evaluate three dimensions of suicide ideation, including: active suicidal desire, specific plans for suicide, and passive suicidal desire. A total score on the scale is obtained by adding the values from the first nineteen items. Scores may range from 0 to 38, with high scores representing high levels of suicidal ideation. The last two items of the 21-item BSS, which are not included in the calculation of the BSS scores, are used to identify a history of past suicide attempts and the individual’s level of motivation to die in the most recent suicide attempt.

The BSS has good internal consistency. Coefficient alphas range from .87 ( Beck & Steer, 1993 ) to .93 ( Beck, Steer, & Ranieri, 1988 ). Cronbach's alpha in the current sample was .93. Moreover, the validity of the BSS has been well established. Researchers have reported positive correlations between BSS scores and other predictors of suicide, including subjective self-report and a history of previous suicide attempts ( Beck & Steer, 1993 ), and clinician ratings of suicidality ( Beck et al., 1988 ).

Cognitive Distortions

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck & Steer, 1988 ) was used to assess each participant’s level of hopelessness. This scale is a self-report measure composed of 20 true/false items that assess the degree to which an individual has negative expectancies regarding events in his or her future. Scores on the BHS range from 0 (no hopelessness) to 20 (extreme hopelessness). The BHS exhibits high levels of reliability. Estimates of internal consistency range from .84 ( Hill, Gallagher, Thompson, & Ishida, 1988 ) to .93 ( Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974 ). In the current sample Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

Research investigating the validity of the BHS has been extensive. The content validity of the BHS was deemed adequate by a panel of clinicians ( Beck et al., 1974 ). As well, high scores on the BHS are positively correlated with clinician ratings of patient hopelessness ( Ammerman, 1988 ) and suicide intent and completion ( Beck & Steer, 1988 ; Beck et al., 1974 ). In addition, the BHS has excellent predictive validity. Based on the results of several longitudinal studies involving suicidal patients, Beck and colleagues reported that a score of 9 or more on the BHS identified 94% of the patients who ultimately completed suicide ( Beck, Brown, Berchick, Stewart, & Steer, 1990 ; Beck, Steer, Kovacs, & Garrison, 1985 ).

A General Attitudes Scale (GAS) was developed for the present study to measure the degree to which each participant endorsed positive or negative attitudes about themselves, others (in general), his/her future, life, and death. Participants were asked to rate their attitudes (over the past two weeks) for each of these categories (listed as “yourself,” “others (in general),” “your future,” “life,” and death”) using a Likert-type scale, where 1 = extremely negative, and 7 = extremely positive.

The psychometric properties of the GAS have yet to be fully established. The first four items, those that represented positive appraisals of self, other, future, and life all yielded significant positive inter-item correlations ranging from .39 to .62 at ( p < .01). The estimate of internal consistency for these first 4 items was .81. The positive appraisal of death demonstrated only one significant association, which was a negative correlation with positive appraisal of other ( r = -.11, p < .05). In terms of concurrent validity, it is notable that the positive appraisals of self (GAS-S) and of future (GAS-F) both demonstrated significant negative correlations with the BHS, with coefficients of r = -.53, p < .01 and r = -.63, p < .01, respectively.

Cognitive Deficits

The Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI; D’Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 1995 , 1998 ) was utilized to assess each participant’s problem-solving ability. The SPSI is a 25-item self-report questionnaire comprised of five scales including: (1) Positive Problem Orientation (SPSI-PPO: a measure of positive orientation toward problem-solving), (2) Negative Problem Orientation (SPSI-NPO: a measure of a dysfunctional and inhibitive cognitive set regarding problem-solving), (3) Rational Problem Solving Scale (SPSI-R: evaluates the deliberate, rational, and systematic application of effective problem-solving strategies and techniques), (4) Impulsivity/Carelessness Problem-Solving Sc ale (SPSI-I: evaluates hasty attempts at problem-solving in the absence of planned and thoughtful deliberation), and (5) Avoidant Problem Solving Scale (SPSI-R-A: assesses the tendency to avoid engaging in active problem-solving). For each of the 25 items on the SPSI-R, participants are asked to indicate on a five-point Likert–type scale (ranging from 0 = “Not at all true of me” to 4 = “Extremely true of me ”) how they typically respond to problems in general. Each scale score may range from 0 to 20.

The SPSI scales have demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability (α range = .65 – 96; D’Zurilla & Nezu, 1990 ; Maydeu-Olivares, Rodríguez-Fornells, Gómez-Benito, & D’Zurilla, 2000 ; Robichaud & Dugas, 2005 ; Sadowski, Moore, & Kelley, 1994 ). When assessing construct validity, researchers have found that within clinical populations, SPSI-R scores are negatively correlated with hopelessness and an increased risk of suicidal behavior ( Faccini, 1992 ). Further, researchers have reported that SPSI-R scores have utility for discriminating between suicide attempters and both non-suicidal psychiatric patients and non-suicidal controls ( Fitzpatrick, Witte, & Schmidt, 2005 ; Sadowski & Kelley, 1993 ). The SPSI-R and SPSI-A both differentiated recent suicide attempters from a normative sample ( Ghahramanlou-Holloway, Bhar, Brown, Olsen, & Beck, 2012 ).

In the present study, only two of the scales of the SPSI were utilized as indicators of problem-solving deficits in the proposed model. These two scales, which included the SPSI-R and the SPSI-A, were selected for use in the current study as previous research has demonstrated a significant relationship between suicidal thinking and behavior and ineffective problem-solving and problem-solving avoidance (e.g., Orbach et al., 1990 ). In the current sample, the Cronbach's alpha was α = .74 and α = .82 for the SPSI-R and SPSI-A, respectively.

The Embedded Figures Test (EFT) was individually administered to assess each participant’s field-dependence/independence (i.e., cognitive rigidity/flexibility). The EFT ( Oltman, Witkin, Raskin, & Karp, 1971 ) consists of 18 simple geometric figures, the first two of which are used for practice. After the practice trials, the participant is sequentially presented with each of the remaining 16 figures. Beside each simple figure is a more complex geometric design, with the simple figure embedded within it. Using a felt-tipped marker, the participant was asked to outline the embedded figure as quickly as possible, while the test administrator timed the response. One point is given for each correct response, with a total possible score of sixteen for the complete test. The total number of correct responses and the total time to complete all correct responses were calculated. The mean time per correct response was then computed, and this value represents the participant’s score on the test. Higher mean scores are associated with field-dependence (i.e., difficulty in overcoming field embeddedness) and, as such, represent a deficit in cognitive flexibility (i.e., high cognitive rigidity). Good levels of reliability (parallel forms; r = .82) have been established for the EFT ( Oltman et al., 1971 ). Research examining the construct validity of this test has established that high measures of field-dependence are associated with measures of cognitive rigidity and an intolerance of ambiguity ( Witkin, 1965 ).

All participants completed an informed consent and the demographic form. Participants were notified that the goal of the current study was to further our understanding of how mood and thinking processes contribute to the development of suicidal thinking and behavior. They were then administered the self-report questionnaires in a randomized order to control for any order effects. Although small groups of individuals simultaneously completed the study, each participant worked privately and independently on his/her own questionnaires. Each participant was asked in turn to accompany the investigator to an adjoining room to complete the Embedded Figures Test, and then returned to complete the questionnaires. Upon completion of the questionnaires, each individual was then thanked for his/her participation and debriefed. Participants were given a list of community mental health support resources, and individuals who endorsed current suicidal thinking were contacted by the investigator by telephone. In the event that the participant reported distress, referrals were then made to qualified mental health care providers. Participants were observed to be receptive to information on how to access mental health care. Participants were compensated with credit towards an Introductory Psychology course. This study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board (UWO REB). All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the UWO REB and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

The fundamental goal of this study was to assess the fit of the proposed model of suicidal ideation. Cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits were hypothesized to be reciprocally related and associated with suicide ideation, as measured by total scores on the BSS. Furthermore, it was expected that cognitive distortions would have a stronger relation than cognitive deficits with suicide ideation. The correlation matrix for the factors in the model is presented in Table 2 .

Table 2. Correlation Matrix of all Measures in the Hypothesized Model.

Note. n = 397. BSS total = Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; GAS-S = General Attitudes Scale-Self Orientation; GAS-F = General Attitudes Scale-Future Orientation; EFT-Mean time = Embedded Figures Test-Mean time per correct response; SPSI-R = Social Problem-Solving Inventory - Rational; SPSI-A = Social Problem-Solving Inventory - Avoidant Problem-Solving Orientation.

* p < .05. ** p < .01.

Although two of the cognitive deficit indicators (rational problem-solving and cognitive rigidity) were not significantly related to suicide ideation, all other indicators demonstrated significant correlations with the measure of suicide ideation. A further inspection of this correlation matrix indicated that the measure of cognitive rigidity (EFT-mean) was not significantly correlated with any of the variables in the model. Despite these findings, we tested the proposed model in accordance with our hypotheses, given the hypothesized model’s strong theoretical justification.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to assess the integrity and fit of the proposed model. We used the Chi-square (χ 2 ) test, as well as several relative fit indices that are less sensitive to sample size and less affected by model misspecifications ( Hu & Bentler, 1999 ), including the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Values of the TLI, GFI, and CFI that exceed .95, and values of the RMSEA that are .05 or less are indicative of excellent fit to the data ( Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003 ). Analyses were conducted using Mplus version 7.4.

Cognitive Distortions and Deficits Model

Assessing the measurement model.

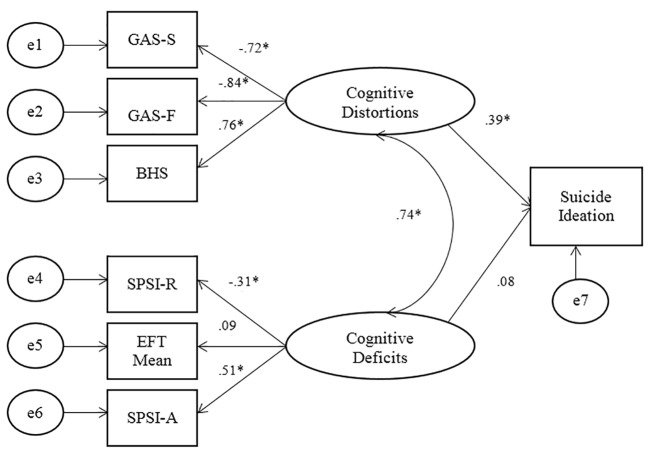

Statistics for the cognitive deficits and distortions model are presented in Figure 1 . All indicators of Cognitive Distortions loaded significantly onto the factor, with BHS (.76, p < .001) loading in a positive direction, and GAS-S (-.72, p < .001), and GAS-F (-.84, p < .001) in a negative direction. For the Cognitive Deficits factor, SPSI-R (-.31, p < .001) loaded negatively, whereas SPSI-A (.51, p < .001) loaded positively. As was the case with the initial model, EFT-Mean loaded in a positive direction (.09, ns ) onto the Cognitive Deficits factor, but the standardized regression weight was very low and was not significant.

Figure 1. SEM statistics for the Modified Cognitive Distortions and Cognitive Deficits Model of Suicidal Thinking.

Note. Suicide Ideation = BSS Total Score; GAS-S = General Attitudes Scale-Self; GAS-F = General Attitudes Scale-Future; BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; SPSI-R = Social Problem-Solving Inventory – Rational problem-solving; EFT-mean = Embedded Figures Test-mean time; SPSI-A = Social Problem-solving Inventory-Avoidant problem-solving.

* p < .001.

Assessing the Fit of the Cognitive Distortions and Deficits Model

Maximum likelihood estimation was utilized to assess the fit of the Cognitive Distortions and Deficits Model. The Chi-Square (χ 2 (12) = 21.34, p = .046) of the model presented in Figure 1 was small, indicating a close fit. Although the Chi-square was significant, the CFI = .98, the TLI = .97, and the RMSEA = .044, all indicative of excellent fit. Contrary to hypotheses, the path from cognitive deficits to suicide ideation was non-significant. The SEM results indicated that eliminating the path from Cognitive Deficits to suicide ideation did not improve the overall fit of the cognitive deficits and distortions model. The resulting Chi-square value actually increased to a value of (χ 2 (13) = 21.55, p = .06). Although this change is not significant (Δχ 2 [1, N = 397] = .21, ns ), it marginally decreases the overall fit of the model, rather than increasing the goodness of fit. Further, eliminating the path from cognitive deficits to suicide ideation did not result in any appreciable increases in the other adjunct fit indices. Subsequent to the elimination of the Cognitive Defi c its to ideation path, the resulting CFI was .98 and the GFI was .98. These resulting values are the same as the initial fit indices that were observed prior to the elimination of the deficits to ideation path. Consequently, the elimination of the path between Cognitive Deficits and suicide ideation did not improve the overall fit of the model. The only notable improvement that resulted from eliminating the path from Cognitive Deficits to suicide ideation was a very small decrease in the RMSEA value from .044 to .041, indicating that this modification provided a slight decrease in the estimate of residual error. Overall, these resulting fit indices are not indicative of a relatively better fit in the model, and thus, do not support the elimination of the path from Cognitive Deficits to suicide ideation.

Considered together, the results of the SEM analyses for the Cognitive Deficits and Distortions Model ( Figure 1 ) indicate that, consistent with hypotheses, cognitive distortions have a direct and significant relation with suicide ideation. Further, also consistent with predictions, cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits have a significant reciprocal relationship. Moreover, as was predicted, cognitive distortions had a much stronger impact on suicidal thinking than did cognitive deficits, which, contrary to hypotheses, did not relate directly with suicide ideation. However, cognitive deficits do have an indirect effect on suicide ideation through their impact on cognitive distortions. Overall, the results of all of the SEM analyses are supportive of the hypothesized model and of the initial hypotheses.

The primary goal of the current study was to assess the integrity of the proposed cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits model of suicidal thinking. The fit indices assessing the fit between the model and the data were all significant, indicating a close fit between the proposed model and the data. As was predicted, cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits had a direct and reciprocal relationship that was significant. Cognitive distortions had a direct association with suicide ideation, whereas cognitive deficits had an indirect relation with suicide ideation through its association with cognitive distortions. The pathway of cognitive deficits to suicide ideation was kept in the model due to theoretical and empirical support for this association in individuals with more severe suicidality (e.g., attempters), and removal of the pathway did not significantly improve model fit. The results of the current study suggest that a lack of adequate problem-solving and a tendency to engage in problem-solving avoidance contribute to hopelessness and to negative evaluations about self and future, both of which are associated with greater suicide ideation. Because the individual avoids solving problems or has difficulty solving them, his or her stressors may be exacerbated, and he or she may therefore feel unable to improve his or her situation, leading to hopelessness and negative thoughts about self and future. The relationship between cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits, and the specific contribution of each in the development of suicide attempts , remains more speculative though. Additional research is required to more definitively assess how cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits interact over time to impact the development of suicide ideation as well as suicide attempts.

The current findings should be interpreted in the context of the study’s strengths and limitations. Although the sample size was considerably large, the study was limited by the fact that it was conducted with a sample of undergraduate students. While this sample was chosen due to the high incidence of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in university students, the use of this sample limits the generalization of the results to a broader population. The relationships in the model need to be further examined in a community and/or clinical sample. Further, the sample in the study was comprised of ideators and non-ideators. Consequently, the proposed relationships in the model also need to be further assessed in a group of suicide attempters, whereby cognitive deficits likely play a more direct role in suicidality ( Richard-Devantoy, Szanto, Butters, Kalkus, & Dombrovski, 2015 ). Furthermore, the study used a cross-sectional design. Future research is needed to examine how a range of cognitive distortions and deficits interact to predict suicide thinking and behaviours over time. Other cognitive distortions and deficits not examined in the current study that could be important for predicting suicide thinking and behaviour (e.g., rumination) should also be included in future models.

A concern regarding the tested model was the low inter-correlations between the indicators of cognitive deficits in the tested model. In particular, the measure of cognitive rigidity used in the current study (EFT) did not correlate with the measures of problem-solving or with suicide ideation. Consequently, there was a degree of misspecification in the measurement model. Previous research has demonstrated that the EFT is a valid and reliable measure of cognitive rigidity, which correlates well with measures of hopelessness and suicide ideation ( Upmanyu et al., 1996 ). However, these patterns were not found in the current study. One reason that could explain this finding is that EFT was a behavioral measure, whereas all other measures were based on self-report; this is an additional limitation of the current study. In addition, there were numerous differences between the current sample and those studied in previous research; other studies used older samples ( Litinsky & Haslam, 1998 ; Marzuk et al., 2005 ; Upmanyu et al., 1996 ), who were culturally distinct (i.e., lived in India; Upmanyu, Narula, & Moein, 1996 ), were inpatients with diagnosed depression ( Marzuk et al., 2005 ), or were psychiatric patients ( Litinsky & Haslam, 1998 ). Past findings may therefore not have been generalizable to the current sample.

The current research makes an important contribution to suicidology research. The proposed cognitive distortions and deficits model of suicide ideation moves beyond examining suicidal thinking in terms of isolated risk factors. Instead, in this new model, suicidal thinking and behavior are discussed in terms of vulnerabilities, including cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits. This new model was not designed to be all-encompassing, but rather, was developed to integrate basic psychological factors and processes that are known to be associated with suicidal thinking. With few exceptions, the proposed model is supported by the current research, and is consistent with extant research findings in the suicidology literature.

The current findings are informative for the assessment and treatment of suicide ideation. Consistent with past research (e.g., Wang, Jiang, Cheung, Sun, & Chan, 2015 ), hopelessness was found to be an important predictor of suicide ideation, as were negative evaluation of self and future. These cognitive distortions are therefore important targets for assessment of suicidality and subsequent treatment. Cognitive behavioral therapies, with their focus on testing negative cognitions, would be one recommended form of treatment ( Nock, Millner, Deming, & Glenn, 2014 ).

In conclusion, the current research study supports the proposed cognitive distortions and deficits model of suicide ideation. The results indicate an almost perfect fit between the data and the proposed model. While it has limitations, the cognitive distortions and cognitive deficits model has important implications for suicidology research and for the assessment and treatment of suicide ideation.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no support to report.

Biographies

Laura Fazakas-DeHoog is a Forensic Psychologist at the Southwest Centre for Forensic Mental Health Care in St. Thomas Ontario as well as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Western Ontario. Her research interests include the causes of suicidal thinking and behavior as well as the prediction of violence recidivism.

Katerina Rnic is a PhD candidate in the Clinical Psychology program at the University of Western Ontario. Her research interests include cognitive vulnerability, stress generation in depression, and how cognitive and behavioural vulnerabilities relate to the generation of and response to depressogenic life events, particularly those involving rejection.

David J. A. Dozois is a Full Professor of Psychology and Director of the Clinical Psychology Graduate Program at the University of Western Ontario. His research focuses on cognitive vulnerability to depression and cognitive-behavioral theory/therapy.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the University of Western Ontario Research Ethics Board (UWO REB). All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the UWO REB and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding: This research was supported in part by a Standard Research Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) and a SSHRC Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Ackerman, R., & DeRubeis, R. J. (1993). The role of cognition in depression. In K. S. Dobson & P. C. Kendall (Eds.), Psychopathology and cognitio n (pp. 83-119). San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alloy L. B., Black S. K., Young M. E., Goldstein K. E., Shapero B. G., Stange J. P., et al. Abramson L. Y. (2012). Cognitive vulnerabilities and depression versus other psychopathology symptoms and diagnoses in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41, 539–560. 10.1080/15374416.2012.703123 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American College Health Association. (2013 ). American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Canadian Reference Group Data Report Spring 2013. Hanover, MD, USA: Author.

- Ammerman, R. T. (1988). Hopelessness Scale. In M. Mersen (Ed.), Dictionary of behavioral assessment techniques (pp. 251-252). University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Pergamon. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Brown G., Berchick R. J., Stewart B. L., Steer R. A. (1990). The relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 190–195. 10.1176/ajp.147.2.190 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Brown G., Steer R. A. (1989). Prediction of eventual suicide in psychiatric inpatients by clinical ratings of hopelessness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 309–310. 10.1037/0022-006X.57.2.309 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1988). Manual for Beck Hopelessness Scale . San Antonio, TX, USA: Psychological Corporation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Manual for Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation . San Antonio, TX, USA: Psychological Corporation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Brown G. (1993). Dysfunctional attitudes and suicidal ideation in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 23, 11–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Kovacs M., Garrison B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A 10-year prospective study of patients hospitalized for suicidal ideation. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 559-563. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Ranieri W. F. (1988). Scale for Suicide Ideation: Psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 499–505. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T., Weissman A., Lester D., Trexler L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 861–865. 10.1037/h0037562 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker-Weidman E. G., Jacobs R. H., Reinecke M. A., Silva S. G., March J. S. (2010). Social problem-solving among adolescents treated for depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48, 11–18. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.08.006 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boergers J., Spirito A., Donaldson D. (1998). Reasons for adolescent suicide attempts: Associations with psychological functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1287–1293. 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00012 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Injury prevention and control: Data and statistics (WISQARS). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Crick N. R., Dodge K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dodge K. A., Crick N. R. (1990). Social information-processing bases of aggressive behavior in children. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 8–22. 10.1177/0146167290161002 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Zurilla T. J., Nezu A. M. (1990). Development and preliminary evaluation of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory. Psychological Assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2, 156–163. 10.1037/1040-3590.2.2.156 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Zurilla, T. J., Nezu, A. M., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (1995). Manual for the Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised . Unpublished manuscript, State University of New York at Stony Brook, NY, USA.

- D’Zurilla, T. J., Nezu, A. M., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (1998). Manual for the Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised. North Tonawanda, New York, NY, USA: Multi-Health Systems. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faccini, L. (1992). The relationship between stress, problem-solving, and suicide. Dissertation Abstracts International, 53 , 03B. (University Microfilms No. 9219142) [ Google Scholar ]

- Fitzpatrick K. K., Witte T. K., Schmidt N. B. (2005). Randomized controlled trial of a brief problem-orientation intervention for suicidal ideation. Behavior Therapy, 36, 323–333. 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80114-5 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garlow S. J., Rosenberg J., Moore J. D., Haas A. P., Koestner B., Hendin H., Nemeroff C. B. (2008). Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: Results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 482–488. 10.1002/da.20321 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M., Bhar S. S., Brown G. K., Olsen C., Beck A. T. (2012). Changes in problem-solving appraisal after cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide. Psychological Medicine, 42, 1185–1193. 10.1017/S0033291711002169 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gothelf D., Apter A., Brand-Gothelf A., Offer N., Ofek H., Tyano S., Pfeffer C. R. (1998). Death concepts in suicidal adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1279–1286. 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00011 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hasley J. P., Ghosh B., Huggins J., Bell M. R., Adler L. E., Shroyer A. L. (2008). A review of “suicidal intent” within the existing suicide literature. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 38, 576–591. 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.576 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hill R. D., Gallagher D., Thompson L. W., Ishida T. (1988). Hopelessness as a measure of suicidal intent in the depressed elderly. Psychology and Aging, 3, 230–232. 10.1037/0882-7974.3.3.230 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hu L., Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis. Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jager-Hyman S., Cunningham A., Wenzel A., Mattei S., Brown G. K., Beck A. T. (2014). Cognitive distortions and suicide attempts. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38, 369–374. 10.1007/s10608-014-9613-0 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kendall, P. C., & Dobson, K. S. (1993). On the nature of cognition and its role in psychopathology. In K. S. Dobson & P. H. Kendall (Eds.), Psychopathology and cognition (pp. 3-19). New York, NY, USA: Academic Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kumar G., Steer R. A. (1995). Psychosocial correlates of suicidal ideation in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 25, 339–346. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuo W.-H., Gallo J. J., Eaton W. W. (2004). Hopelessness, depression, substance disorder, and suicidality: A 13-year community-based study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 497–501. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lakey C. E., Hirsch J. K., Nelson L. A., Nsamenang S. A. (2014). Effects of contingent self-esteem on depressive symptoms and suicidal behavior. Death Studies, 38, 563–570. 10.1080/07481187.2013.809035 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Linda W. P., Marroquín B., Miranda R. (2012). Active and passive problem solving as moderators of the relation between negative life event stress and suicidal ideation among suicide attempters and non-attempters. Archives of Suicide Research, 16, 183–197. 10.1080/13811118.2012.695233 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Linehan M. M., Camper P., Chiles J. A., Strosahl K., Shearin E. N. (1987). Interpersonal problem solving and parasuicide. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 1–12. 10.1007/BF01183128 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Litinsky A. M., Haslam N. (1998). Dichotomous thinking as a sign of suicide risk on the TAT. Journal of Personality Assessment, 71, 368–378. 10.1207/s15327752jpa7103_6 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marzuk P. M., Hartwell N., Leon A. C., Portera L. (2005). Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112, 294–301. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00585.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maydeu-Olivares A., Rodríguez-Fornells A., Gómez-Benito J., D’Zurilla T. J., Jr. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Spanish adaptation of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R). Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 699–708. 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00226-3 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McMillan D., Gilbody S., Beresford E., Neilly L. (2007). Can we predict suicide and non-fatal self-harm with the Beck Hopelessness Scale? A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 37, 769–778. 10.1017/S0033291706009664 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Milich R., Dodge K. A. (1984). Social information processing in child psychiatric populations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 471–489. 10.1007/BF00910660 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Miller A. B., Esposito-Smythers C. (2013). How do cognitive distortions and substance- related problems affect the relationship between child maltreatment and adolescent suicidal ideation? Psychology of Violence, 3, 340–353. 10.1037/a0031355 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Neuringer C. (1979). The semantic perception of life, death, and suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 255–258. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nock, M. K., Millner, A. J., Deming, C. A., & Glenn, C. R. (2014). Depression and suicide. In I. H. Gotlib & C. L. Hammen (Eds.), Handbook of depression (pp. 448-467). New York, NY, USA: Guildford Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Carroll P. W., Berman A. L., Maris R. W., Moscicki E. K., Tanney B. L., Silverman M. M. (1996). Beyond the Tower of Babel: A nomenclature for suicidology. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 26, 237–252. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oltman, P. K., Witkin, H. A., Raskin, E., & Karp, S. A. (1971). A manual for the Embedded Figures Test . Palo Alto, CA, USA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Orbach I., Bar-Joseph H., Dror N. (1990). Styles of problem solving in suicidal individuals. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 20, 56–64. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Orbach I., Blomenson R., Mikulincer M., Gilboa-Schechtman E., Rogolsky M., Retzoni G. (2007). Perceiving a problem-solving task as a threat and suicidal behavior in adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 1010–1034. 10.1521/jscp.2007.26.9.1010 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pollock L. R., Williams J. M. G. (2004). Problem-solving in suicide attempters. Psychological Medicine, 34, 163–167. 10.1017/S0033291703008092 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Richard-Devantoy S., Szanto K., Butters M. A., Kalkus J., Dombrovski A. Y. (2015). Cognitive inhibition in older high‐lethality suicide attempters. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30, 274–283. 10.1002/gps.4138 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Robichaud M., Dugas M. J. (2005). Negative problem orientation (Part II): Construct validity and specificity to worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 403–412. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.008 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sadowski C., Kelley M. L. (1993). Social problem-solving in suicidal adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 121–127. 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.121 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sadowski C., Moore L. A., Kelley M. L. (1994). Psychometric Properties of the Social Problem Solving Inventory (SPSI) with Normal and Emotionally Disturbed Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22, 487–500. 10.1007/BF02168087 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schermelleh-Engel K., Moosbrugger H., Müller H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online, 8, 23–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schotte D. E., Clum G. A. (1987). Problem-solving in suicidal psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 49–54. 10.1037/0022-006X.55.1.49 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Statistics Canada. (n.d.). Suicide. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/help/bb/info/suicide

- Upmanyu V. V., Narula V., Moein L. (1996). A study of suicide ideation: The intervening role of cognitive rigidity. Psychological Studies, 40, 126–131. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y.-y., Jiang N.-z., Cheung E. F. C., Sun H.-w., Chan R. C. K. (2015). Role of depression severity and impulsivity in the relationship between hopelessness and suicidal ideation in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 83–89. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.001 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Witkin H. A. (1965). Psychological differentiation and forms of pathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 70, 317–336. 10.1037/h0022498 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yang B., Clum G. A. (1994). Life stress, social support, and problem-solving skills predictive of depressive symptoms, hopelessness, and suicide ideation in an Asian student population: A test of a model. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 24, 127–139. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (335.3 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2023

An exploration of suicidal ideation and attempts, and care use and unmet need among suicide-ideators in a Belgian population study

- Eva Rens 1 , 2 ,

- Gwendolyn Portzky 3 ,

- Manuel Morrens 2 , 4 ,

- Geert Dom 2 , 5 ,

- Kris Van den Broeck 1 , 2 &

- Mandy Gijzen 3

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 1741 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2649 Accesses

7 Citations

Metrics details

Suicidal ideation, or thinking about death and suicide, is common across all layers of society. The aim of this paper is to add to the understanding of suicidal ideation in the general population, as well as help-seeking behaviors and perceived unmet mental health needs among those who report suicidal thoughts.

The research is part of a representative population-based survey study of mental wellbeing in Antwerp (Flanders, Belgium) carried out in 2021. A total of 1202 participants between 15 and 80 years old answered the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), and an additional question about suicide plans. Participation was by invitation only and possible online or via a postal paper questionnaire. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to explore the association between both current suicidal ideation and self-reported lifetime suicide attempt with the sociodemographic factors age, gender, educational level, origin and financial distress. Moreover, formal care use for mental health was examined among those experiencing suicidal ideation, and logistic regression analyses were used to assess associated sociodemographic factors. Finally, perceived unmet mental health needs were assessed among suicide ideators.

The point-prevalence of suicidal ideation was 8.6% and was higher among younger age groups and individuals reporting financial distress. The lifetime-prevalence of suicide attempts is 6.5% and was higher in younger people and individuals with a primary educational level and with financial distress. About half (45.6%) of those with suicidal ideation consulted a professional for mental health problems in the past twelve months. Men and those with a primary educational level were less likely to seek help. Half of suicide ideators without care use perceived some need for mental health care, and a third of suicide ideators who used care perceived the obtained help as insufficient, resulting in a population prevalence of 3.6% suicide ideators with a fully or partially perceived unmet need.

Conclusions

The prevalence of suicide attempts, suicidal ideation and unmet needs among suicide-ideators is high in this Belgian sample. Mental health care need perception in suicide ideators needs further investigation.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Suicide is a global public health issue and one of the leading causes of death, accounting for one in 100 deaths [ 1 ]. In 2019, the age-standardized suicide rate was 8.96 deaths per 100.000 people globally, and 10.5 deaths per 100.000 people in Europe [ 2 ]. Furthermore, it is estimated that there are more than 20 suicide attempts per suicide death [ 3 ]. Suicide is the result of a complex interaction of neurobiological and psychological susceptibilities, and it is often associated with stressful events and poor conditions such as loneliness [ 4 , 5 ]. Suicidality is often considered a continuum, ranging from suicidal ideation to suicide attempts. ‘Suicidal ideation’ involves a range of thoughts, wishes and preoccupations with death and the possibility of ending one's own life [ 6 ]. Also within suicidal ideation, a distinction is often made between transient thoughts and passive ideation (i.e., thoughts about being death in general), and persistent ruminations and active ideation (i.e., concrete suicidal thoughts or plans) [ 7 , 8 , 9 ].

A meta-analysis found that the prevalence of passive suicidal ideation ranges from 2% point-prevalence to 11% for lifetime ideation in the general population, and even up to 47% for lifetime ideation in psychiatric samples [ 7 ]. This is in line with results from the World Mental Health Surveys carried out in 21 countries in the early 2000s, demonstrating that the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide plans and suicide attempts are 9%, 3% and 3%, respectively [ 10 ]. Between 2015 and 2019, a total 4.3% US adults reported suicidal thoughts, 1.3% a suicide plan and 0.6% a suicide attempt in the preceding year [ 11 ].

As can be expected, these are intercorrelated: among those with lifetime suicidal ideation, one in three also had a lifetime suicide plan and/or a suicide attempt [ 10 ]. Suicidal ideation is often transient, as some studies report that the majority of suicide ideators at baseline do no longer report suicidal thoughts after a follow-up period of one and a half year [ 12 , 13 ]. However, suicidal ideation generally fluctuates greatly, even in a span of a few days, and stronger fluctuations were found to be associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation [ 14 ].

Although fewer than one in 200 ideators actually die from suicide, it remains a major risk factor for suicide [ 12 ]. People expressing suicidal ideation are four times more likely to die by suicide compared to non-suicide-ideators, with an absolute suicide risk of 0.2% in non-psychiatric and 1.4% in psychiatric populations, but the highest relative risks in non-psychiatric populations [ 15 ]. A past suicide attempt is an especially strong and robust risk factor for completed suicide, even up to thirty years after the first attempt [ 16 ]. A study using medical records found a prevalence of 5.4% suicide deaths in a cohort of 1490 individuals of whom a first suicide attempt was recorded during a 20 year period, of which 40.7% did not die on the first attempt [ 17 ].

It is commonly found that socio-demographic risk-factors of suicidal ideation and behavior include being female, younger age and lower socio-economic status [ 7 , 8 , 10 , 18 ]. The relation between gender and suicide is complex. Suicidal ideation and nonfatal suicide attempts are higher in women, but men are two to four times more likely to die from suicide, often referred to as the ‘suicidal behavior gender paradox’ [ 19 , 20 ]. One of the main reasons for this is that males use more lethal methods when committing suicide, but even when the same method is used, male suicide attempts are more often classified under ‘serious attempts’ where there is a clear intent to die [ 20 , 21 ].

It is estimated that one in three people with suicidal thoughts (approximately one in two in high-income countries) seeks help for their mental health in a given year, although it is unclear what proportion of help seekers also explicitly seeks help for suicidality [ 22 , 23 ]. This demonstrates the high unmet need among suicidal people, but formal help-seeking generally increases as suicide risk increases [ 24 ]. Key barriers to seeking help include a preference to solve problems on their own, a lack of perceived need for care, fear of stigmatization and stigmatizing attitudes. On the other hand, social support and mental health literacy facilitate professional help-seeking [ 23 , 25 ].

A systematic review showed that 57% of all people who died from suicide had a lifetime mental health care contact, and 31% had a contact with mental health services in the final twelve months [ 26 ]. Male sex and both younger and older age are consistently associated with non-receipt of mental health services [ 27 ]. An analysis of US nationally representative data between 2008 and 2019 found that mental health care use among suicide attempters has not increased [ 28 ]. However, some people may also use other help sources for suicidality that fall outside of the traditional mental health field. For example, the internet nowadays offers numerous anonymous support resources which may have caused a ‘help seeking shift’, and there is some evidence that especially younger and higher-risk groups seek suicide-related help online [ 29 ].

Regarding perceived or subjective care needs, a study found that 35% of those who experienced suicidal ideation in the past twelve months perceived an unmet mental health need at some point. On the other hand, looking at those with suicidal ideation who did not receive any treatment during that period, two thirds did not perceive an unmet mental health need [ 30 ]. Another study found that differences in perceived unmet needs and health care use between persons with a common mental disorder with and without suicidal ideation were largely explained by severity of the symptomatology, as persons with suicidal ideation typically have more severe mental illness. Moreover, even when receiving mental health care, persons with suicidal ideation were more likely to perceive this care as insufficient or inadequate [ 31 ]. In 2019, a total of 46% of suicide attempters in the US reported needing mental health care but did not receive it, and this did not significantly change during the decade [ 28 ].

The study described in this paper examines the point prevalence and risk factors of suicidal ideation in a Belgian province (Antwerp) based on a population survey study, as well as the lifetime prevalence of self-reported suicide attempts, and twelve-month health care use for mental health and unmet need perception among suicide ideators. Suicide numbers are high in Belgium, with an age-standardized prevalence of 13.93 deaths per 100.000 people in 2019 [ 2 ]. Prior research from the four-yearly national Belgian health survey (2018) found that 13.9% of Belgians ever seriously thought about suicide that time, of whom 4.3% in a 12-month period. Four percent ever attempted suicide and two in thousand did so in the past twelve months [ 32 ].

However, it is unclear how many of Belgian suicide ideators had previous contacts with mental health services and perceive an unmet treatment need. The current paper explores the correlates of suicidal ideation and attempts, help seeking and the perception of unmet need among those with suicidal thoughts in Antwerp (Belgium), with the aim to add to the understanding of the (unmet) needs regarding suicide in the general population.

As part of a research project which aims to assess the level of (unmet) mental health needs in the Antwerp Province in the Flemish region of Belgium, a sample of 5000 Antwerp citizens aged 15 to 80 years was invited to participate in a mental wellbeing survey between May and August 2021. The sample was randomly drawn from the national register and was stratified by gender, municipality, age and nationality (Belgian versus non-Belgian). Invited individuals were asked to fill in a self-report questionnaire and could participate online or through a paper questionnaire sent by postal mail. The paper questionnaire was available in the official language Dutch only, but the online questionnaire was available in six languages that are commonly spoken in Antwerp: Dutch, French, English, German, Polish and Arabic. Ethical approval was obtained from all participants.

The following socio-demographic information was included in the current study: age category (15 – 25y old, 26 – 39y old, 40 – 64y old, 65 – 80y old), gender (male, female), origin (geographic region of Europe, non-Europe), educational attainment (primary education i.e. no high school degree, secondary education or higher) and financial distress (self-reported financial difficulties or not).

Suicidal ideation was measured with five yes/no questions, of which four questions were adapted from the ultra-brief Ask Suicide Screening Questions (ASQ) Suicide Screening Toolkit from the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which is a validated tool for identifying adults and youth at elevated suicide risk in all clinical settings [ 33 , 34 ]. Note that the question about ‘thoughts of killing yourself right now’ was not included as this is more of relevance in a clinical setting to assess suicide risk. Also, a question about suicide plans was added. The original ASQ uses the term ‘killing yourself’, but we decided to use ‘committing suicide’ in the English version as this is more in line with the common Dutch-language terminology that was used in the Dutch version. Current suicidal ideation was considered present when one or more of the four items about suicidal ideation in the past two weeks were answered positively. Question 5, lifetime suicide attempt, was not considered for current suicidal ideation. The items are mentioned in Table 1 in the Results section.

Health care use for mental health problems was assessed by asking the individuals whether they consulted a professional for their mental health in the past twelve months. Those reporting health care use for mental health were asked which professional was consulted (a general practitioner (GP), and/or a psychologist, and/or a psychiatrist) and whether they were prescribed medication for their mental health. Finally, questions about perceived unmet needs for mental health care were asked. Concretely, those with suicidal ideation who reported using health care for their mental health in the past twelve months were asked whether they thought the received help was sufficient. On the other hand, those who did not report using health care for mental health were asked whether they thought they needed help in the past twelve months but did not seek it. Those answering yes are defined as having an unmet need for mental health care.

The observations were weighed to match the Antwerp population using inverse probability weighting to correct for differences in response rate (i.e., larger weight for individuals from subgroups with higher non-response) between age categories, gender and nationality (Belgian versus non-Belgian) [ 35 ]. Descriptive characteristics of the sample and the prevalence of suicidal ideation, lifetime suicide attempts, health care use for mental health problems and perceived unmet mental health need are reported using weighted percentages.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses are used to assess the relationship between sociodemographic variables (sex, age, education, origin, financial distress) and the presence of suicidal ideation and lifetime suicide attempts in the general population. Next, logistic regression analyses were used to assess the sociodemographic associates of mental health care use among those reporting suicidal ideation. Crude odds ratios (COR) are presented for the univariate regression analyses, and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for the multivariate analyses. Finally, Chi Square tests were used to examine the associations between perceived unmet needs and suicidal ideation.

A total of 1202 Antwerp citizens participated in the survey and had no missing demographic data or data about suicidality (24% of the invited sample). In the weighted sample, 49.7% of the participants were men, 10.8% has a non-European place of birth and 13.6% has no secondary education. The mean age is 45.5 years old.

The item scores are presented in Table 1 . Overall, 103 persons or 8.6% of all participants experienced suicidal ideation in the past few weeks. A total of 44.2% of suicide ideators answered yes to only one suicidal ideation item, 18.6% to two items, 29.1% to three items and 8.1% to all four suicidal ideation items. Only 11 people (0.9%) reported suicidal plans in the past few weeks. A lifetime suicide attempt was reported by 78 individuals (6.5%). Among those reporting a suicide attempt, 63.1% has no current suicidal ideation, and 2.4% of the total sample reported both suicidal ideation and a lifetime suicide attempt.

The sociodemographic distribution of current suicidal ideation together with the results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regressions is shown in Table 2 . No gender difference was found. Age is a strong risk factor, with a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation among younger age groups. In the multivariate model, the prevalence of suicidal ideation among people aged 65 and older (3.4%) is significantly lower than the prevalence among 26 to 44 year old’s (10.3%; OR = 3.60, 95% CI 1.58 – 8.19) and 15 to 25 year old’s (15.0%; OR = 5.68, 95% CI 2.38 – 13.54). Twelve percent of those without and eight percent of those with secondary education reported suicidal ideation, but this was not significant. Suicidal ideation did not differ between those with a European or non-European place of birth in the univariate analysis, but non-Europeans were significantly less likely to ideate suicide in the multivariate analysis (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.19—0.88). Finally, self-reported financial distress is a major risk factor of suicidal ideation: 6.6% of those without financial difficulties reported suicidal ideation, as compared to 18.4% of those with financial difficulties (OR = 4.15, 95% CI 2.59 – 6.64).

The sociodemographic distribution of the presence of a lifetime suicide attempt and the results of the logistic regressions are shown in Table 3 . There were no effects of gender or origin. People in the younger age groups were significantly more likely to report a lifetime suicide attempt. In the multivariate regression analysis, those between 26 and 44 years old had a higher odds of reporting a suicide attempt than the oldest age group (OR = 2.96, 95% CI 1.23 – 7.14). Moreover, people with a secondary education or higher are less likely to have attempted suicide in their life (OR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.21—0.70). The effect of financial distress is strongly significant with a three times higher odds of lifetime suicide attempts among those with self-reported financial problems (OR = 3.36, 95% CI 2.01 – 5.64).

More than one in six (17.1%, n = 206) of all participants used health care for their mental health in the past twelve months. A total of 22.8% ( n = 47) of all people with a mental health related health care contact reported suicidal ideation. About half ( n = 47, 45.6%) of those reporting suicidal ideation consulted a professional for mental health problems in the past twelve months, compared to 14.5% ( n = 159) of those without suicidal ideation. Therefore, there are 4.7% people with suicidal ideation who do not use health care for their mental health in the total sample. Of all help seekers with suicidal ideation, 70.2% consulted a GP, 66.0% a psychologist, and 27.7% a psychiatrist. Moreover, 48.9% was also prescribed medication for their mental health.

Table 4 shows the sociodemographic distribution and associated factors of help-seeking among those reporting suicidal ideation. Note that the small subsample of suicide ideators ( N = 103) raises very wide confidence intervals and the results should be interpreted taking into account this large statistical uncertainty. Sixty percent of women experiencing suicidal ideation sought help for their mental health, as compared to 28.2% of men (OR = 4.01, 95% CI 1.62 – 9.92). As regards educational level, 51.9% of people with at least a secondary degree as compared to 22.2% of those with a primary degree in the group of suicide ideators sought professional help (OR = 4.63, 95% CI 1.15 – 18.59).

Finally, questions were asked about perceived (unmet) needs for mental healthcare. Among those with suicidal ideation but no health care use for their mental health, half (50.0%, 28 out of 56) reported that they perceived some need for mental health care in the past twelve months but that they did not seek help. As a comparison, this prevalence is 9.9% (93 out of 940) among non-help-seekers without suicidal ideation, and a Chi square test showed that there is a significant association between suicidal ideation and reporting fully unmet mental health needs (X 2 (1, N = 996) = 79.65, p < 0.001).

Secondly, those who consulted a professional in the past twelve months were asked whether they thought they were sufficiently helped with their mental health problem. Help-seekers with suicidal ideation were more likely to report that the help was insufficient (34.0%, 16 out of 47) compared to help-seekers without suicidal ideation (20.1%, 32 out of 159) ((X 2 (1, N = 206) = 3.93, p = 0.047). As a total of 75 out of 103 suicide ideators either sought help or perceived a need for mental health care in the absence of help, it can be concluded that 72.8% of suicide ideators perceived some mental health need.

Overall, persons with suicidal ideation with a fully unmet need (no care use for mental health) make up 2.3% of the sample, and persons with suicidal ideation with a partially unmet need (insufficient care obtained) 1.3%, leading to a total population prevalence of 3.6% unmet suicidal ideation needs.

The study described in this paper explored the local prevalence and correlates of past-weeks suicidal ideation and lifetime suicide attempts in the general population in the province of Antwerp (Belgium), as well as help seeking for mental health and the perception of unmet mental health need among those experiencing suicidal ideation.

A strength of the study is the use of a representative probability sample. Moreover, participation was possible in six languages and both online and through paper-and-pencil, which allows vulnerable groups such as foreign-language immigrants and those without internet access to participate. However, some bias because of self-selection cannot be avoided, for example, because persons with mental health problems may be more likely to participate. Also, the smaller sample sizes in some subgroups raise large statistical uncertainty. The findings should only be interpreted in the context of descriptive and exploratory research.

Suicidal ideation is high in the sample, with a higher relative prevalence among younger people, people reporting financial difficulties and Europeans. Based on the item-scores, 5.3% and 0.9% respectively thought and planned to commit suicide in the past few weeks,. In comparison, 3.3% of the Flemish population (i.e., Flanders is the Belgian part where Antwerp is located) seriously thought about suicide in the past twelve months according to the national health survey in 2018, mostly women and young people [ 32 ]. A meta-analysis found that there is a point-prevalence of 2% of passive suicidal ideation in the general population worldwide [ 7 ]. It is unclear whether this is due to a general increase in suicidal ideation, given that many of the included prevalence studies are at least ten years old. The high level of suicidal ideation in women and younger age groups is in line with research reporting an alarming increasing trend in suicidal ideation in young and middle-aged women [ 36 ]. Another possible explanation is that suicidal ideation might be especially high in Belgium. As regards actual suicides, it is estimated that the Belgian suicide mortality rate is very high, about 1.7 times higher than the EU-average [ 37 ]. It must be mentioned that this should be interpreted with caution due to international differences in registration and data quality.

On the other hand, other studies also reported even higher level of suicidal ideation in 2021 and argue that this can at least partly be explained by the COVID-19. A systematic review reported a pooled prevalence of 11.5% of suicidal ideation in the general population during the early stages of COVID-19, but this includes twelve-month prevalence estimates as well [ 38 ]. Also in Belgium, several survey studies pointed to increased rates of suicidal ideation. In June 2021, which is during the study period, 10.5% of respondents reported having seriously considered suicide in the past 12 months, and in young people (18–29 years old) this percentage rises to 17% [ 39 ]. Regarding suicide attempts, 0.7% of all respondents and 2.0 of young people reported having attempted suicide in the past 12 months [ 39 ]. It should be noted that the use of non-probability samples during the COVID-19 pandemic may have influenced these findings, but nevertheless these numbers are high and suggest a small elevation in suicidality during the pandemic [ 40 ]. No official suicide mortality numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Belgium are available up to date, but registrations on suicides and attempts from the Federal Police showed no increase [ 41 ].

The prevalence of reporting ever having attempted suicide is very high in the sample. More than one in sixteen people (6.5%) claimed ever having attempted suicide, which is remarkably more than the number of the BHIS 2018, where 3.4% of Flemish people reported a lifetime suicide attempt. Also globally, 3% reported a suicide attempt in the World Mental Health Surveys twenty years ago [ 10 ]. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear.

Among people reporting financial distress in our sample, even 14.6% ever attempted suicide. Given that a prior suicide attempt is considered the most critical risk factor for suicide in the general population, this group needs extra attention [ 17 ]. The same holds for lower educational level, which is another proxy of socio-economic status. Further research should examine if the high suicidality is explained by the financial stress itself, or (a combination of) other social vulnerability factors or possible associated risk factors such as lower social support or poor neighborhood.

As regards help seeking, it was found that half of those with current suicidal ideation reported using health services for their mental health in the past twelve months, especially a GP and/or psychologist, and half were also prescribed medication for a mental health problem. Persons with suicidal ideation make up more than one-fifth of the population of mental health care users. Men and people with a lower educational attainment who experience suicidal ideation are less likely to seek professional help.

The lower use of mental health services and higher level of unmet needs among men with mental health problems is a consistent finding in the literature [ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. In general, men are less likely to perceive a need for mental health care and have less favorable attitudes towards psychological openness and help-seeking for mental health problems [ 43 ]. This can be explained by self-stigma due to conformity to traditional masculine norms such as emotional control and toughness [ 46 , 47 ]. In line with this, a study found that more men than women who died by suicide in the UK were not in contact with mental health services a year before dying [ 48 ].