Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.5 Identifying and Overcoming Problem-Solving Barriers

The 9 dot problem.

Here is another popular type of puzzle that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper (Mayer, 1992).

Did you figure it out?

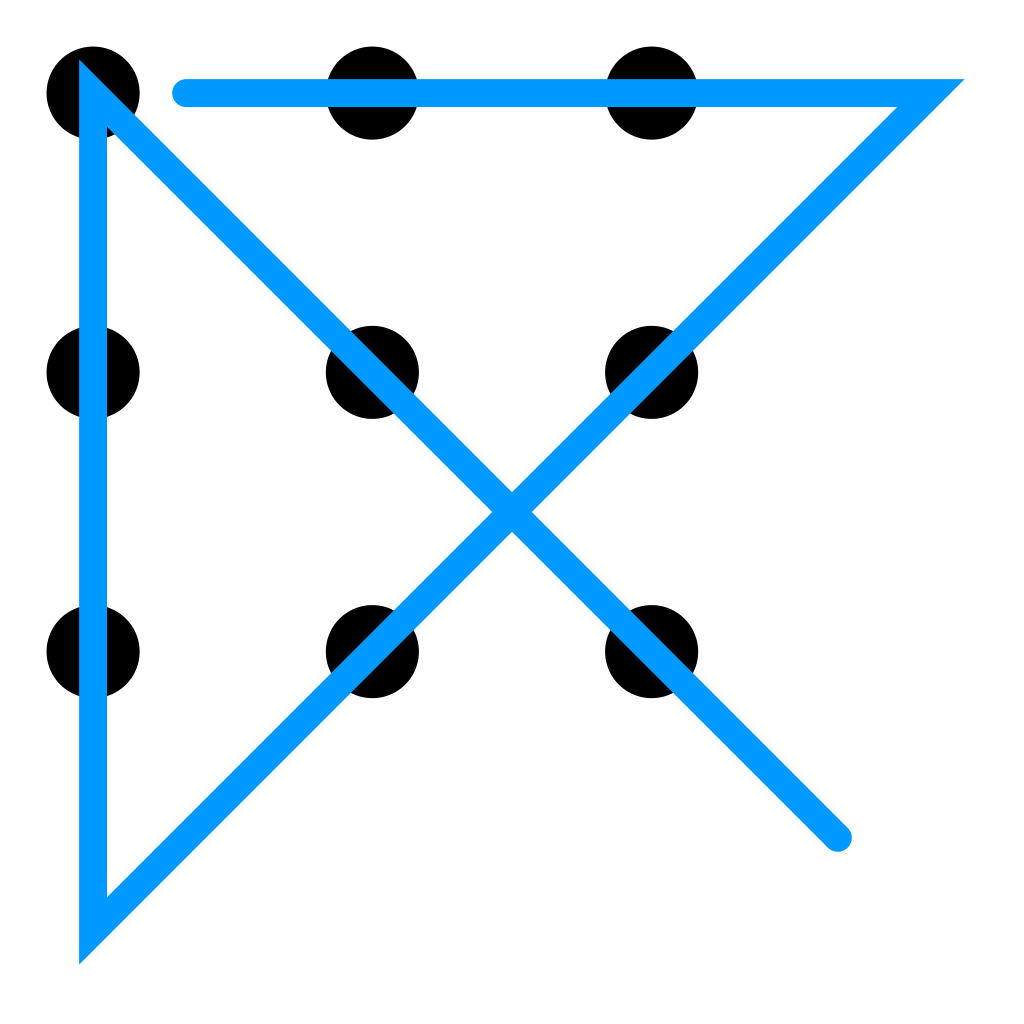

Solve the puzzle with 4 contiguous segments:

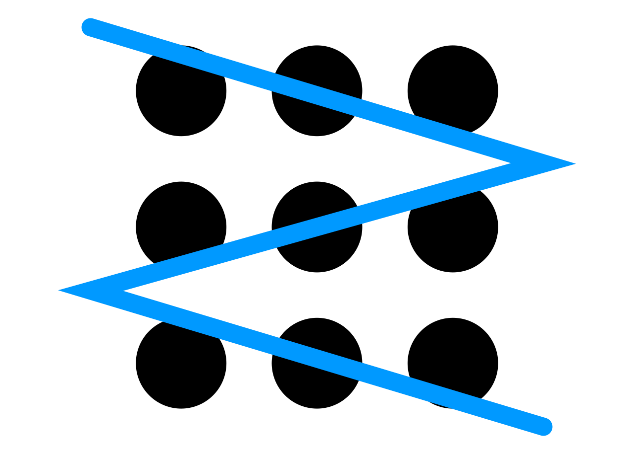

Now, solve the puzzle with just 3 contiguous segments!

Remember, the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem or represents a problem often facilitates or hinders problem solving. If information is misunderstood, thought about, or used inappropriately, then mistakes are likely – if indeed the problem can be solved at all.

So we not only metaphorically, but sometimes literally, want to “think outside the box” to facilitate creative problem solving. Until we had this insight with the problem, we were having “ representation failure . ”

Put differently, there were obstacles in problem representation, the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. Initially, we were understanding and organizing information the information in a manner that hindered successful problem solving.

Likely related to our initial representation failure, we likely made the unwarranted assumption or unwarranted expectation that we needed to stay inside some imaginary box. Note that in some contexts, we do want to stay inside some imaginary box. Further, we often have a history of parents and teachers encouraging us to stay inside the lines, leading to a negative transfer of learning in which past learning or training negatively impacts performance on new tasks.

If information is misunderstood or used inappropriately and/or unwarranted assumptions are made, then mistakes are likely – if indeed the problem can be solved at all. With the nine-dot matrix problem, for example, construing the instruction to draw four lines as meaning “draw four lines entirely within the imaginary box matrix” means that the problem simply could not be solved.

A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now .

In the example of the Nine-Dot Problem described above, students often tried one solution after another, but each solution was constrained by being stuck or set in their way of thinking about and response not to extend any line beyond the matrix of an imaginary box.

Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked . The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway , keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck , but she just needs to go to another doorway instead of trying to get out through the locked door.

Functional Fixedness

Fu nctional fixedness is a type of mental set where you do not consider using something for a purpose other than what it was designed for or is typically used for.

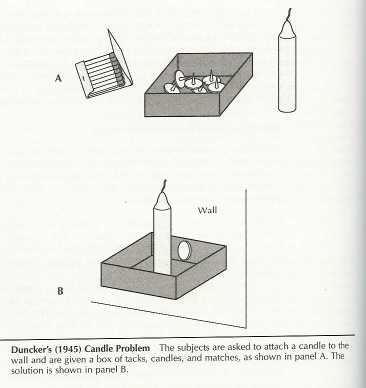

Functional fixedness concerns the solution of object-use problems. The basic idea is that when the usual way of using an object is emphasized , it will be far more difficult for a person to use that object in a novel manner . An example of this effect of being fixed on the typical use of objects is Duncker’s (194 5 ) candle problem .

Imagine you are given a box of matches, some candles and tacks. On the wall of the room there is a corkboard. Your task is to fix the candle to the corkboard in such a way that no wax will drop on the floor when the candle is lit. – Got an idea?

Explanation: The clue is just the following. When people are confronted with a problem and given certain objects to solve it, it is difficult for them to figure out that they could use them in a different (not so familiar or obvious) way s .

In this example the box needs to be recognized as a support for the candle rather than as a container. People tend to be stuck or fixed on the box as a container, and not think of or notice other uses or functions (like to support a candle).

Until we had this insight with the Candle Problem, we were having “ representation failure ”, or we were understanding and organizing information the information in a manner that hindered successful problem solving.

Likely related to our initial representation failure, we likely made the unwarranted assumption or unwarranted expectation that we needed to think about and use the box as a container (only).

Finally, check this link as an interesting way to review some of these concepts and relate them to your life. https://prezi.com/3o1o7yqdsabl/functional-fixedness/

A process in which previous learning obstructs or interferes with present learning. For instance, tennis players who learn racquetball must often unlearn their tendency to take huge, muscular swings with the shoulder and upper arm.

A temporary readiness to perform certain psychological functions that influences the response to a situation or stimulus, such as the tendency to apply a previously successful technique in solving a new problem.

The tendency to perceive an object only in terms of its most common (or intended) use.

Cognitive Psychology Copyright © by Robert Graham and Scott Griffin. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Identifying Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology

Problem-solving is a key aspect of psychology, essential for understanding and overcoming challenges in our daily lives. There are common barriers that can hinder our ability to effectively solve problems. From mental blocks to confirmation bias, these obstacles can impede our progress.

In this article, we will explore the various barriers to problem-solving in psychology, as well as strategies to overcome them. By addressing these challenges head-on, we can unlock the benefits of improved problem-solving skills and mental agility.

- Identifying and overcoming barriers to problem-solving in psychology can lead to more effective and efficient solutions.

- Some common barriers include mental blocks, confirmation bias, and functional fixedness, which can all limit critical thinking and creativity.

- Mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, and collaborating with others can help overcome these barriers and lead to more successful problem-solving.

- 1 What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

- 2 Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

- 3.1 Mental Blocks

- 3.2 Confirmation Bias

- 3.3 Functional Fixedness

- 3.4 Lack of Creativity

- 3.5 Emotional Barriers

- 3.6 Cultural Influences

- 4.1 Divergent Thinking

- 4.2 Mindfulness Techniques

- 4.3 Seeking Different Perspectives

- 4.4 Challenging Assumptions

- 4.5 Collaborating with Others

- 5 What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

- 6 Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Problem-Solving in Psychology?

Problem-solving in psychology refers to the cognitive processes through which individuals identify and overcome obstacles or challenges to reach a desired goal, drawing on various mental processes and strategies.

In the realm of cognitive psychology, problem-solving is a key area of study that delves into how people use algorithms and heuristics to tackle complex issues. Algorithms are systematic step-by-step procedures that guarantee a solution, whereas heuristics are mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that provide efficient solutions, albeit without certainty. Understanding these mental processes is crucial in exploring how individuals approach different types of problems and make decisions based on their problem-solving strategies.

Why Is Problem-Solving Important in Psychology?

Problem-solving holds significant importance in psychology as it facilitates the discovery of new insights, enhances understanding of complex issues, and fosters effective actions based on informed decisions.

Assumptions play a crucial role in problem-solving processes, influencing how individuals perceive and approach challenges. By challenging these assumptions, individuals can break through mental barriers and explore creative solutions.

Functional fixedness, a cognitive bias where individuals restrict the use of objects to their traditional functions, can hinder problem-solving. Overcoming functional fixedness involves reevaluating the purpose of objects, leading to innovative problem-solving strategies.

Through problem-solving, psychologists uncover underlying patterns in behavior, delve into subconscious motivations, and offer practical interventions to improve mental well-being.

What Are the Common Barriers to Problem-Solving in Psychology?

In psychology, common barriers to problem-solving include mental blocks , confirmation bias , functional fixedness, lack of creativity, emotional barriers, and cultural influences that hinder the application of knowledge and resources to overcome challenges.

Mental blocks refer to the difficulty in generating new ideas or solutions due to preconceived notions or past experiences. Confirmation bias, on the other hand, is the tendency to search for, interpret, or prioritize information that confirms existing beliefs or hypotheses, while disregarding opposing evidence.

Functional fixedness limits problem-solving by constraining individuals to view objects or concepts in their traditional uses, inhibiting creative approaches. Lack of creativity impedes the ability to think outside the box and consider unconventional solutions.

Emotional barriers such as fear, stress, or anxiety can halt progress by clouding judgment and hindering clear decision-making. Cultural influences may introduce unique perspectives or expectations that clash with effective problem-solving strategies, complicating the resolution process.

Mental Blocks

Mental blocks in problem-solving occur when individuals struggle to consider all relevant information, fall into a fixed mental set, or become fixated on irrelevant details, hindering progress and creative solutions.

For instance, irrelevant information can lead to mental blocks by distracting individuals from focusing on the key elements required to solve a problem effectively. This could involve getting caught up in minor details that have no real impact on the overall solution. A fixed mental set, formed by previous experiences or patterns, can limit one’s ability to approach a problem from new perspectives, restricting innovative thinking.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias, a common barrier in problem-solving, leads individuals to seek information that confirms their existing knowledge or assumptions, potentially overlooking contradictory data and hindering objective analysis.

This cognitive bias affects decision-making and problem-solving processes by creating a tendency to favor information that aligns with one’s beliefs, rather than considering all perspectives.

- One effective method to mitigate confirmation bias is by actively challenging assumptions through critical thinking.

- By questioning the validity of existing beliefs and seeking out diverse viewpoints, individuals can counteract the tendency to only consider information that confirms their preconceptions.

- Another strategy is to promote a culture of open-mindedness and encourage constructive debate within teams to foster a more comprehensive evaluation of data.

Functional Fixedness

Functional fixedness restricts problem-solving by limiting individuals to conventional uses of objects, impeding the discovery of innovative solutions and hindering the application of insightful approaches to challenges.

For instance, when faced with a task that requires a candle to be mounted on a wall to provide lighting, someone bound by functional fixedness may struggle to see the potential solution of using the candle wax as an adhesive instead of solely perceiving the candle’s purpose as a light source.

This mental rigidity often leads individuals to overlook unconventional or creative methods, which can stifle their ability to find effective problem-solving strategies.

To combat this cognitive limitation, fostering divergent thinking, encouraging experimentation, and promoting flexibility in approaching tasks can help individuals break free from functional fixedness and unlock their creativity.

Lack of Creativity

A lack of creativity poses a significant barrier to problem-solving, limiting the potential for improvement and hindering flexible thinking required to generate novel solutions and address complex challenges.

When individuals are unable to think outside the box and explore unconventional approaches, they may find themselves stuck in repetitive patterns without breakthroughs.

Flexibility is key to overcoming this hurdle, allowing individuals to adapt their perspectives, pivot when necessary, and consider multiple viewpoints to arrive at innovative solutions.

Encouraging a culture that embraces experimentation, values diverse ideas, and fosters an environment of continuous learning can fuel creativity and push problem-solving capabilities to new heights.

Emotional Barriers

Emotional barriers, such as fear of failure, can impede problem-solving by creating anxiety, reducing risk-taking behavior, and hindering effective collaboration with others, limiting the exploration of innovative solutions.

When individuals are held back by the fear of failure, it often stems from a deep-seated worry about making mistakes or being judged negatively. This fear can lead to hesitation in decision-making processes and reluctance to explore unconventional approaches, ultimately hindering the ability to discover creative solutions. To overcome this obstacle, it is essential to cultivate a positive emotional environment that fosters trust, resilience, and open communication among team members. Encouraging a mindset that embraces failure as a stepping stone to success can enable individuals to take risks, learn from setbacks, and collaborate effectively to overcome challenges.

Cultural Influences

Cultural influences can act as barriers to problem-solving by imposing rigid norms, limiting flexibility in thinking, and hindering effective communication and collaboration among diverse individuals with varying perspectives.

When individuals from different cultural backgrounds come together to solve problems, the ingrained values and beliefs they hold can shape their approaches and methods.

For example, in some cultures, decisiveness and quick decision-making are highly valued, while in others, a consensus-building process is preferred.

Understanding and recognizing these differences is crucial for navigating through the cultural barriers that might arise during collaborative problem-solving.

How Can These Barriers Be Overcome?

These barriers to problem-solving in psychology can be overcome through various strategies such as divergent thinking, mindfulness techniques, seeking different perspectives, challenging assumptions, and collaborating with others to leverage diverse insights and foster critical thinking.

Engaging in divergent thinking , which involves generating multiple solutions or viewpoints for a single issue, can help break away from conventional problem-solving methods. By encouraging a free flow of ideas without immediate judgment, individuals can explore innovative paths that may lead to breakthrough solutions. Actively seeking diverse perspectives from individuals with varied backgrounds, experiences, and expertise can offer fresh insights that challenge existing assumptions and broaden the problem-solving scope. This diversity of viewpoints can spark creativity and unconventional approaches that enhance problem-solving outcomes.

Divergent Thinking

Divergent thinking enhances problem-solving by encouraging creative exploration of multiple solutions, breaking habitual thought patterns, and fostering flexibility in generating innovative ideas to address challenges.

When individuals engage in divergent thinking, they open up their minds to various possibilities and perspectives. Instead of being constrained by conventional norms, a person might ideate freely without limitations. This leads to out-of-the-box solutions that can revolutionize how problems are approached. Divergent thinking sparks creativity by allowing unconventional ideas to surface and flourish.

For example, imagine a team tasked with redesigning a city park. Instead of sticking to traditional layouts, they might brainstorm wild concepts like turning the park into a futuristic playground, a pop-up art gallery space, or a wildlife sanctuary. Such diverse ideas stem from divergent thinking and push boundaries beyond the ordinary.

Mindfulness Techniques

Mindfulness techniques can aid problem-solving by promoting present-moment awareness, reducing cognitive biases, and fostering a habit of continuous learning that enhances adaptability and open-mindedness in addressing challenges.

Engaging in regular mindfulness practices encourages individuals to stay grounded in the current moment, allowing them to detach from preconceived notions and biases that could cloud judgment. By cultivating a non-judgmental attitude towards thoughts and emotions, people develop the capacity to observe situations from a neutral perspective, facilitating clearer decision-making processes. Mindfulness techniques facilitate the development of a growth mindset, where one acknowledges mistakes as opportunities for learning and improvement rather than failures.

Seeking Different Perspectives

Seeking different perspectives in problem-solving involves tapping into diverse resources, engaging in effective communication, and considering alternative viewpoints to broaden understanding and identify innovative solutions to complex issues.

Collaboration among individuals with various backgrounds and experiences can offer fresh insights and approaches to tackling challenges. By fostering an environment where all voices are valued and heard, teams can leverage the collective wisdom and creativity present in diverse perspectives. For example, in the tech industry, companies like Google encourage cross-functional teams to work together, harnessing diverse skill sets to develop groundbreaking technologies.

To incorporate diverse viewpoints, one can implement brainstorming sessions that involve individuals from different departments or disciplines to encourage out-of-the-box thinking. Another effective method is to conduct surveys or focus groups to gather input from a wide range of stakeholders and ensure inclusivity in decision-making processes.

Challenging Assumptions

Challenging assumptions is a key strategy in problem-solving, as it prompts individuals to critically evaluate preconceived notions, gain new insights, and expand their knowledge base to approach challenges from fresh perspectives.

By questioning established beliefs or ways of thinking, individuals open the door to innovative solutions and original perspectives. Stepping outside the boundaries of conventional wisdom enables problem solvers to see beyond limitations and explore uncharted territories. This process not only fosters creativity but also encourages a culture of continuous improvement where learning thrives. Daring to challenge assumptions can unveil hidden opportunities and untapped potential in problem-solving scenarios, leading to breakthroughs and advancements that were previously overlooked.

- One effective technique to challenge assumptions is through brainstorming sessions that encourage participants to voice unconventional ideas without judgment.

- Additionally, adopting a beginner’s mindset can help in questioning assumptions, as newcomers often bring a fresh perspective unburdened by past biases.

Collaborating with Others

Collaborating with others in problem-solving fosters flexibility, encourages open communication, and leverages collective intelligence to navigate complex challenges, drawing on diverse perspectives and expertise to generate innovative solutions.

Effective collaboration enables individuals to combine strengths and talents, pooling resources to tackle problems that may seem insurmountable when approached individually. By working together, team members can break down barriers and silos that often hinder progress, leading to more efficient problem-solving processes and better outcomes.

Collaboration also promotes a sense of shared purpose and increases overall engagement, as team members feel valued and enableed to contribute their unique perspectives. To foster successful collaboration, it is crucial to establish clear goals, roles, and communication channels, ensuring that everyone is aligned towards a common objective.

What Are the Benefits of Overcoming These Barriers?

Overcoming the barriers to problem-solving in psychology leads to significant benefits such as improved critical thinking skills, enhanced knowledge acquisition, and the ability to address complex issues with greater creativity and adaptability.

By mastering the art of problem-solving, individuals in the field of psychology can also cultivate resilience and perseverance, two essential traits that contribute to personal growth and success.

When confronting and overcoming cognitive obstacles, individuals develop a deeper understanding of their own cognitive processes and behavioral patterns, enabling them to make informed decisions and overcome challenges more effectively.

Continuous learning and adaptability play a pivotal role in problem-solving, allowing psychologists to stay updated with the latest research, techniques, and methodologies that enhance their problem-solving capabilities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Similar posts.

Exploring the Concept of Social Scripts in Psychology

The article was last updated by Marcus Wong on February 5, 2024. Have you ever found yourself acting in a certain way in social situations…

Uncovering the Meaning of Blind Spots in Psychology

The article was last updated by Dr. Emily Tan on February 8, 2024. Ever find yourself making decisions that seem irrational in hindsight? Or perhaps…

Unveiling Memory Stages: Psychology Experts and the Second Stage

The article was last updated by Rachel Liu on February 5, 2024. Have you ever wondered how your memory works and the different stages it…

Exploring Stress Tests in Evolutionary Psychology

The article was last updated by Ethan Clarke on February 8, 2024. Have you ever wondered why humans behave the way they do? Evolutionary psychology…

Informed Consent in Psychology: Understanding its Gestures and Limitations

The article was last updated by Julian Torres on February 5, 2024. In psychology, informed consent plays a crucial role in ensuring ethical practices and…

Exploring Dr. Spellman’s Contributions to Psychology: What Did He Study?

The article was last updated by Lena Nguyen on February 9, 2024. Have you ever wondered who Dr. Spellman is and what contributions he made…

More From Forbes

The six main barriers against problem-solving and how to overcome them.

Challenges. Disputes. Dilemmas. Obstacles. Troubles. Issues. Headaches.

- The uniqueness of every different issue makes the need for an also adapted and individualized solution.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Business people discussing the plan at office photo credit: Getty

There are more than thirty different ways to call all those unpleasant and stressful situations which prevent us from directly achieving what we want to achieve. Life is full of them. This is why the ability to solve problems in an effective and timely manner without any impediments is considered to be one of the most key and critical skill for resolutive and successful leaders. But is not just leaders or top managers facing the way forward. According to a Harvard Bussiness Review survey , people's skills depends on their level on the organization and their particular job and activities. However, when coming to problem-solving, there is a remarkable consistency about the importance of it within all the different measured organization levels.

There are small problems and big problems. Those ones that we laugh about and those that take our sleep away. Problems that affect just us or our whole company. Issues that need to be resolved proactively and others that require us to wait and observe. There is a special kind of problem for every day of our lives, but all of them responds to a common denominator: addressing them adequately. It is our ability to do so what makes the difference between success and failure.

Problems manifest themselves in many different ways. As inconsistent results or performance. As a failure toward standards. As discrepancies between expectations and reality. The uniqueness of every different issue makes the need for an also adapted and individualized solution. This is why finding the way forward can be sometimes tricky. There are many reasons why it is difficult to find a solution to a problem, but you can find the six more common causes and the way to overcome them!

1. Difficulty to recognize that there is a problem

Nobody likes to be wrong. “Cognitive dissonance is what we feel when the self-concept — I’m smart, I’m kind, I’m convinced this belief is true — is threatened by evidence that we did something that wasn’t smart, that we did something that hurt another person, that the belief isn’t true,” explains Carol Tavris.

Problems and mistakes are not easy to digest. To reduce this cognitive dissonance, we need to modify our self-concept or well deny the evidence. Many times is just easier to simply turn our back to an issue and blindly keep going. But the only way to end it up to satisfactory is to make an effort to recognize and accept the evidence. Being wrong is human and until the problem is not acknowledged solutions will never materialize. To fully accept that something is not going the way it should, the easiest way is to focus on the benefits of new approaches and always remain non-judgemental about the causes. Sometimes we may be are afraid of the costs in terms of resources, time and physical or mental efforts that working for the solution may eventually bring. We may need then to project ourselves in all the fatalistic consequences that we will finally encounter in case we continue sunk in the problem. Sometimes we really need to visualize the disaster before accepting a need for change.

2. Huge size problem

Yes! We clearly know that something is going wrong. But the issue is so big that there is no way we can try to solve it without blowing our life into pieces. Fair enough. Some problems are so big that it is not possible to find at once a solution for them. But we can always break them into smaller pieces and visualize the different steps and actions that we could eventually undertake to get to our final goal. Make sure you do not lose sight of the original problem!

3. Poorly framed problem

Without the proper framing, there is no certainty about the appropriate focus on the right problem. Asking the relevant questions is a crucial aspect to it. Does your frame of the problem capture its real essence? Do you have all the background information needed? Can you rephrase the problem and it is still understandable? Have you explored it from different perspectives? Are different people able to understand your frame for the problem correctly? Answering to the right problem in the right way depends 95% on the correct framing of it!

'If I have an hour to solve a problem, I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about the solution' (Albert Einstein)

4. Lack of respect for rhythms

There is always a right time for preparation, a right time for action and a right time for patience. Respecting the rhythms of a problem is directly link to the success of the solution. Acting too quickly or waiting too long can have real counterproductive effects. There is a need for enough time to gather information and understand all the different upshots of a planned solution. A balance of action is crucial to avoid both eagerness and laxity. Waiting for the proper time to take action is sometimes the most complicated part of it.

5. Lack of problem'roots identification

It is quite often that we feel something is not going the way it should without clearly identifying what the exact problematic issue is. We are able to frame all the negative effects and consequences, but we do not really get to appropriately verbalized what the problem is all together. Consequently, we tend to fix the symptoms without getting to the real causes. It is as common as dangerous and not sustainable for problem-solving.

Make sure that you have a clear picture of what are the roots of the problem and what are just the manifestations or ramifications of it. Double loop always to make sure that you are not patching over the symptoms but getting to the heart of the matter.

6. Failure to identify the involved parts

Take time to figure out and consult every simple part involved in the problem as well as affected by the possible solution. Problems and solutions always have at the core human needs and impacts. Failing to identify and take into consideration the human factor in the problem-solving process will prevent the whole mechanism from reaching the desired final goal.

'We always hope for the easy fix: the one simple change that will erase a problem in a stroke. But few things in life work this way. Instead, success requires making a hundred small steps go right - one after the other, no slipups, no goofs, everyone pitching in.' ( Atul Gawande)

- Editorial Standards

- Forbes Accolades

Barriers to Effective Problem Solving

Learning how to effectively solve problems is difficult and takes time and continual adaptation. There are several common barriers to successful CPS, including:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to only search for or interpret information that confirms a person’s existing ideas. People misinterpret or disregard data that doesn’t align with their beliefs.

- Mental Set: People’s inclination to solve problems using the same tactics they have used to solve problems in the past. While this can sometimes be a useful strategy (see Analogical Thinking in a later section), it often limits inventiveness and creativity.

- Functional Fixedness: This is another form of narrow thinking, where people become “stuck” thinking in a certain way and are unable to be flexible or change perspective.

- Unnecessary Constraints: When people are overwhelmed with a problem, they can invent and impose additional limits on solution avenues. To avoid doing this, maintain a structured, level-headed approach to evaluating causes, effects, and potential solutions.

- Groupthink: Be wary of the tendency for group members to agree with each other — this might be out of conflict avoidance, path of least resistance, or fear of speaking up. While this agreeableness might make meetings run smoothly, it can actually stunt creativity and idea generation, therefore limiting the success of your chosen solution.

- Irrelevant Information: The tendency to pile on multiple problems and factors that may not even be related to the challenge at hand. This can cloud the team’s ability to find direct, targeted solutions.

- Paradigm Blindness : This is found in people who are unwilling to adapt or change their worldview, outlook on a particular problem, or typical way of processing information. This can erode the effectiveness of problem solving techniques because they are not aware of the narrowness of their thinking, and therefore cannot think or act outside of their comfort zone.

According to Jaffa, the primary barrier of effective problem solving is rigidity. “The most common things people say are, ‘We’ve never done it before,’ or ‘We’ve always done it this way.’” While these feelings are natural, Jaffa explains that this rigid thinking actually precludes teams from identifying creative, inventive solutions that result in the greatest benefit. “The biggest barrier to creative problem solving is a lack of awareness – and commitment to – training employees in state-of-the-art creative problem-solving techniques,” Mattimore explains. “We teach our clients how to use ideation techniques (as many as two-dozen different creative thinking techniques) to help them generate more and better ideas. Ideation techniques use specific and customized stimuli, or ‘thought triggers’ to inspire new thinking and new ideas.” MacLeod adds that ineffective or rushed leadership is another common culprit. “We're always in a rush to fix quickly,” she says. “Sometimes leaders just solve problems themselves, making unilateral decisions to save time. But the investment is well worth it — leaders will have less on their plates if they can teach and eventually trust the team to resolve. Teams feel empowered and engagement and investment increases.”

Image Courtesy of Pexels.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IResearchNet

Problem Solving

Problem solving, a fundamental cognitive process deeply rooted in psychology, plays a pivotal role in various aspects of human existence, especially within educational contexts. This article delves into the nature of problem solving, exploring its theoretical underpinnings, the cognitive and psychological processes that underlie it, and the application of problem-solving skills within educational settings and the broader real world. With a focus on both theory and practice, this article underscores the significance of cultivating problem-solving abilities as a cornerstone of cognitive development and innovation, shedding light on its applications in fields ranging from education to clinical psychology and beyond, thereby paving the way for future research and intervention in this critical domain of human cognition.

Introduction

Problem solving, a quintessential cognitive process deeply embedded in the domains of psychology and education, serves as a linchpin for human intellectual development and adaptation to the ever-evolving challenges of the world. The fundamental capacity to identify, analyze, and surmount obstacles is intrinsic to human nature and has been a subject of profound interest for psychologists, educators, and researchers alike. This article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of problem solving, investigating its theoretical foundations, cognitive intricacies, and practical applications in educational contexts. With a clear understanding of its multifaceted nature, we will elucidate the pivotal role that problem solving plays in enhancing learning, fostering creativity, and promoting cognitive growth, setting the stage for a detailed examination of its significance in both psychology and education. In the continuum of psychological research and educational practice, problem solving stands as a cornerstone, enabling individuals to navigate the complexities of their world. This article’s thesis asserts that problem solving is not merely a cognitive skill but a dynamic process with profound implications for intellectual growth and application in diverse real-world contexts.

The Nature of Problem Solving

Problem solving, within the realm of psychology, refers to the cognitive process through which individuals identify, analyze, and resolve challenges or obstacles to achieve a desired goal. It encompasses a range of mental activities, such as perception, memory, reasoning, and decision-making, aimed at devising effective solutions in the face of uncertainty or complexity.

Problem solving as a subject of inquiry has drawn from various theoretical perspectives, each offering unique insights into its nature. Among the seminal theories, Gestalt psychology has highlighted the role of insight and restructuring in problem solving, emphasizing that individuals often reorganize their mental representations to attain solutions. Information processing theories, inspired by computer models, emphasize the systematic and step-by-step nature of problem solving, likening it to information retrieval and manipulation. Furthermore, cognitive psychology has provided a comprehensive framework for understanding problem solving by examining the underlying cognitive processes involved, such as attention, memory, and decision-making. These theoretical foundations collectively offer a richer comprehension of how humans engage in and approach problem-solving tasks.

Problem solving is not a monolithic process but a series of interrelated stages that individuals progress through. These stages are integral to the overall problem-solving process, and they include:

- Problem Representation: At the outset, individuals must clearly define and represent the problem they face. This involves grasping the nature of the problem, identifying its constraints, and understanding the relationships between various elements.

- Goal Setting: Setting a clear and attainable goal is essential for effective problem solving. This step involves specifying the desired outcome or solution and establishing criteria for success.

- Solution Generation: In this stage, individuals generate potential solutions to the problem. This often involves brainstorming, creative thinking, and the exploration of different strategies to overcome the obstacles presented by the problem.

- Solution Evaluation: After generating potential solutions, individuals must evaluate these alternatives to determine their feasibility and effectiveness. This involves comparing solutions, considering potential consequences, and making choices based on the criteria established in the goal-setting phase.

These components collectively form the roadmap for navigating the terrain of problem solving and provide a structured approach to addressing challenges effectively. Understanding these stages is crucial for both researchers studying problem solving and educators aiming to foster problem-solving skills in learners.

Cognitive and Psychological Aspects of Problem Solving

Problem solving is intricately tied to a range of cognitive processes, each contributing to the effectiveness of the problem-solving endeavor.

- Perception: Perception serves as the initial gateway in problem solving. It involves the gathering and interpretation of sensory information from the environment. Effective perception allows individuals to identify relevant cues and patterns within a problem, aiding in problem representation and understanding.

- Memory: Memory is crucial in problem solving as it enables the retrieval of relevant information from past experiences, learned strategies, and knowledge. Working memory, in particular, helps individuals maintain and manipulate information while navigating through the various stages of problem solving.

- Reasoning: Reasoning encompasses logical and critical thinking processes that guide the generation and evaluation of potential solutions. Deductive and inductive reasoning, as well as analogical reasoning, play vital roles in identifying relationships and formulating hypotheses.

While problem solving is a universal cognitive function, individuals differ in their problem-solving skills due to various factors.

- Intelligence: Intelligence, as measured by IQ or related assessments, significantly influences problem-solving abilities. Higher levels of intelligence are often associated with better problem-solving performance, as individuals with greater cognitive resources can process information more efficiently and effectively.

- Creativity: Creativity is a crucial factor in problem solving, especially in situations that require innovative solutions. Creative individuals tend to approach problems with fresh perspectives, making novel connections and generating unconventional solutions.

- Expertise: Expertise in a specific domain enhances problem-solving abilities within that domain. Experts possess a wealth of knowledge and experience, allowing them to recognize patterns and solutions more readily. However, expertise can sometimes lead to domain-specific biases or difficulties in adapting to new problem types.

Despite the cognitive processes and individual differences that contribute to effective problem solving, individuals often encounter barriers that impede their progress. Recognizing and overcoming these barriers is crucial for successful problem solving.

- Functional Fixedness: Functional fixedness is a cognitive bias that limits problem solving by causing individuals to perceive objects or concepts only in their traditional or “fixed” roles. Overcoming functional fixedness requires the ability to see alternative uses and functions for objects or ideas.

- Confirmation Bias: Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek, interpret, and remember information that confirms preexisting beliefs or hypotheses. This bias can hinder objective evaluation of potential solutions, as individuals may favor information that aligns with their initial perspectives.

- Mental Sets: Mental sets are cognitive frameworks or problem-solving strategies that individuals habitually use. While mental sets can be helpful in certain contexts, they can also limit creativity and flexibility when faced with new problems. Recognizing and breaking out of mental sets is essential for overcoming this barrier.

Understanding these cognitive processes, individual differences, and common obstacles provides valuable insights into the intricacies of problem solving and offers a foundation for improving problem-solving skills and strategies in both educational and practical settings.

Problem Solving in Educational Settings

Problem solving holds a central position in educational psychology, as it is a fundamental skill that empowers students to navigate the complexities of the learning process and prepares them for real-world challenges. It goes beyond rote memorization and standardized testing, allowing students to apply critical thinking, creativity, and analytical skills to authentic problems. Problem-solving tasks in educational settings range from solving mathematical equations to tackling complex issues in subjects like science, history, and literature. These tasks not only bolster subject-specific knowledge but also cultivate transferable skills that extend beyond the classroom.

Problem-solving skills offer numerous advantages to both educators and students. For teachers, integrating problem-solving tasks into the curriculum allows for more engaging and dynamic instruction, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Additionally, it provides educators with insights into students’ thought processes and areas where additional support may be needed. Students, on the other hand, benefit from the development of critical thinking, analytical reasoning, and creativity. These skills are transferable to various life situations, enhancing students’ abilities to solve complex real-world problems and adapt to a rapidly changing society.

Teaching problem-solving skills is a dynamic process that requires effective pedagogical approaches. In K-12 education, educators often use methods such as the problem-based learning (PBL) approach, where students work on open-ended, real-world problems, fostering self-directed learning and collaboration. Higher education institutions, on the other hand, employ strategies like case-based learning, simulations, and design thinking to promote problem solving within specialized disciplines. Additionally, educators use scaffolding techniques to provide support and guidance as students develop their problem-solving abilities. In both K-12 and higher education, a key component is metacognition, which helps students become aware of their thought processes and adapt their problem-solving strategies as needed.

Assessing problem-solving abilities in educational settings involves a combination of formative and summative assessments. Formative assessments, including classroom discussions, peer evaluations, and self-assessments, provide ongoing feedback and opportunities for improvement. Summative assessments may include standardized tests designed to evaluate problem-solving skills within a particular subject area. Performance-based assessments, such as essays, projects, and presentations, offer a holistic view of students’ problem-solving capabilities. Rubrics and scoring guides are often used to ensure consistency in assessment, allowing educators to measure not only the correctness of answers but also the quality of the problem-solving process. The evolving field of educational technology has also introduced computer-based simulations and adaptive learning platforms, enabling precise measurement and tailored feedback on students’ problem-solving performance.

Understanding the pivotal role of problem solving in educational psychology, the diverse pedagogical strategies for teaching it, and the methods for assessing and measuring problem-solving abilities equips educators and students with the tools necessary to thrive in educational environments and beyond. Problem solving remains a cornerstone of 21st-century education, preparing students to meet the complex challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Applications and Practical Implications

Problem solving is not confined to the classroom; it extends its influence to various real-world contexts, showcasing its relevance and impact. In business, problem solving is the driving force behind product development, process improvement, and conflict resolution. For instance, companies often use problem-solving methodologies like Six Sigma to identify and rectify issues in manufacturing. In healthcare, medical professionals employ problem-solving skills to diagnose complex illnesses and devise treatment plans. Additionally, technology advancements frequently stem from creative problem solving, as engineers and developers tackle challenges in software, hardware, and systems design. Real-world problem solving transcends specific domains, as individuals in diverse fields address multifaceted issues by drawing upon their cognitive abilities and creative problem-solving strategies.

Clinical psychology recognizes the profound therapeutic potential of problem-solving techniques. Problem-solving therapy (PST) is an evidence-based approach that focuses on helping individuals develop effective strategies for coping with emotional and interpersonal challenges. PST equips individuals with the skills to define problems, set realistic goals, generate solutions, and evaluate their effectiveness. This approach has shown efficacy in treating conditions like depression, anxiety, and stress, emphasizing the role of problem-solving abilities in enhancing emotional well-being. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) incorporates problem-solving elements to help individuals challenge and modify dysfunctional thought patterns, reinforcing the importance of cognitive processes in addressing psychological distress.

Problem solving is the bedrock of innovation and creativity in various fields. Innovators and creative thinkers use problem-solving skills to identify unmet needs, devise novel solutions, and overcome obstacles. Design thinking, a problem-solving approach, is instrumental in product design, architecture, and user experience design, fostering innovative solutions grounded in human needs. Moreover, creative industries like art, literature, and music rely on problem-solving abilities to transcend conventional boundaries and produce groundbreaking works. By exploring alternative perspectives, making connections, and persistently seeking solutions, creative individuals harness problem-solving processes to ignite innovation and drive progress in all facets of human endeavor.

Understanding the practical applications of problem solving in business, healthcare, technology, and its therapeutic significance in clinical psychology, as well as its indispensable role in nurturing innovation and creativity, underscores its universal value. Problem solving is not only a cognitive skill but also a dynamic force that shapes and improves the world we inhabit, enhancing the quality of life and promoting progress and discovery.

In summary, problem solving stands as an indispensable cornerstone within the domains of psychology and education. This article has explored the multifaceted nature of problem solving, from its theoretical foundations rooted in Gestalt psychology, information processing theories, and cognitive psychology to its integral components of problem representation, goal setting, solution generation, and solution evaluation. It has delved into the cognitive processes underpinning effective problem solving, including perception, memory, and reasoning, as well as the impact of individual differences such as intelligence, creativity, and expertise. Common barriers to problem solving, including functional fixedness, confirmation bias, and mental sets, have been examined in-depth.

The significance of problem solving in educational settings was elucidated, underscoring its pivotal role in fostering critical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Pedagogical approaches and assessment methods were discussed, providing educators with insights into effective strategies for teaching and evaluating problem-solving skills in K-12 and higher education.

Furthermore, the practical implications of problem solving were demonstrated in the real world, where it serves as the driving force behind advancements in business, healthcare, and technology. In clinical psychology, problem-solving therapies offer effective interventions for emotional and psychological well-being. The symbiotic relationship between problem solving and innovation and creativity was explored, highlighting the role of this cognitive process in pushing the boundaries of human accomplishment.

As we conclude, it is evident that problem solving is not merely a skill but a dynamic process with profound implications. It enables individuals to navigate the complexities of their environment, fostering intellectual growth, adaptability, and innovation. Future research in the field of problem solving should continue to explore the intricate cognitive processes involved, individual differences that influence problem-solving abilities, and innovative teaching methods in educational settings. In practice, educators and clinicians should continue to incorporate problem-solving strategies to empower individuals with the tools necessary for success in education, personal development, and the ever-evolving challenges of the real world. Problem solving remains a steadfast ally in the pursuit of knowledge, progress, and the enhancement of human potential.

References:

- Anderson, J. R. (1995). Cognitive psychology and its implications. W. H. Freeman.

- Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89-195). Academic Press.

- Duncker, K. (1945). On problem-solving. Psychological Monographs, 58(5), i-113.

- Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1980). Analogical problem solving. Cognitive Psychology, 12(3), 306-355.

- Jonassen, D. H., & Hung, W. (2008). All problems are not equal: Implications for problem-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 2(2), 6.

- Kitchener, K. S., & King, P. M. (1981). Reflective judgment: Concepts of justification and their relation to age and education. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 2(2), 89-116.

- Luchins, A. S. (1942). Mechanization in problem solving: The effect of Einstellung. Psychological Monographs, 54(6), i-95.

- Mayer, R. E. (1992). Thinking, problem solving, cognition. W. H. Freeman.

- Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving (Vol. 104). Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination: Principles and procedures of creative problem solving (3rd ed.). Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Polya, G. (1945). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method. Princeton University Press.

- Sternberg, R. J. (2003). Wisdom, intelligence, and creativity synthesized. Cambridge University Press.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Put differently, there were obstacles in problem representation, the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. Initially, we were understanding and organizing information the information in a manner that hindered successful problem solving.

In psychology, common barriers to problem-solving include mental blocks, confirmation bias, functional fixedness, lack of creativity, emotional barriers, and cultural influences that hinder the application of knowledge and resources to overcome challenges.

Problem-solving involves taking certain steps and using psychological strategies. Learn problem-solving techniques and how to overcome obstacles to solving problems.

There are many reasons why it is difficult to find a solution to a problem, but you can find the six more common causes and the way to overcome them! 1. Difficulty to recognize that there is a...

A mental set is a tendency to only see solutions that have worked in the past. This type of fixed thinking can make it difficult to come up with solutions and can impede the problem-solving process. For example, that you are trying to solve a math problem in algebra class.

Learning how to effectively solve problems is difficult and takes time and continual adaptation. There are several common barriers to successful CPS, including: Confirmation Bias: The tendency to only search for or interpret information that confirms a person’s existing ideas.

Functional fixedness and the response set are obstacles in problem representation, the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. If information is misunderstood or used inappropriately, then mistakes are likely—if indeed the problem can be solved at all.

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

Got a problem to solve? From school to relationships, we look at examples of problem-solving strategies and how to use them.

Problem solving, within the realm of psychology, refers to the cognitive process through which individuals identify, analyze, and resolve challenges or obstacles to achieve a desired goal.