- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Discuss the Significance of Your Research

- 6-minute read

- 10th April 2023

Introduction

Research papers can be a real headache for college students . As a student, your research needs to be credible enough to support your thesis statement. You must also ensure you’ve discussed the literature review, findings, and results.

However, it’s also important to discuss the significance of your research . Your potential audience will care deeply about this. It will also help you conduct your research. By knowing the impact of your research, you’ll understand what important questions to answer.

If you’d like to know more about the impact of your research, read on! We’ll talk about why it’s important and how to discuss it in your paper.

What Is the Significance of Research?

This is the potential impact of your research on the field of study. It includes contributions from new knowledge from the research and those who would benefit from it. You should present this before conducting research, so you need to be aware of current issues associated with the thesis before discussing the significance of the research.

Why Does the Significance of Research Matter?

Potential readers need to know why your research is worth pursuing. Discussing the significance of research answers the following questions:

● Why should people read your research paper ?

● How will your research contribute to the current knowledge related to your topic?

● What potential impact will it have on the community and professionals in the field?

Not including the significance of research in your paper would be like a knight trying to fight a dragon without weapons.

Where Do I Discuss the Significance of Research in My Paper?

As previously mentioned, the significance of research comes before you conduct it. Therefore, you should discuss the significance of your research in the Introduction section. Your reader should know the problem statement and hypothesis beforehand.

Steps to Discussing the Significance of Your Research

Discussing the significance of research might seem like a loaded question, so we’ve outlined some steps to help you tackle it.

Step 1: The Research Problem

The problem statement can reveal clues about the outcome of your research. Your research should provide answers to the problem, which is beneficial to all those concerned. For example, imagine the problem statement is, “To what extent do elementary and high school teachers believe cyberbullying affects student performance?”

Learning teachers’ opinions on the effects of cyberbullying on student performance could result in the following:

● Increased public awareness of cyberbullying in elementary and high schools

● Teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying negatively affecting student performance

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Whether cyberbullying is more prevalent in elementary or high schools

The research problem will steer your research in the right direction, so it’s best to start with the problem statement.

Step 2: Existing Literature in the Field

Think about current information on your topic, and then find out what information is missing. Are there any areas that haven’t been explored? Your research should add new information to the literature, so be sure to state this in your discussion. You’ll need to know the current literature on your topic anyway, as this is part of your literature review section .

Step 3: Your Research’s Impact on Society

Inform your readers about the impact on society your research could have on it. For example, in the study about teachers’ opinions on cyberbullying, you could mention that your research will educate the community about teachers’ perceptions of cyberbullying as it affects student performance. As a result, the community will know how many teachers believe cyberbullying affects student performance.

You can also mention specific individuals and institutions that would benefit from your study. In the example of cyberbullying, you might indicate that school principals and superintendents would benefit from your research.

Step 4: Future Studies in the Field

Next, discuss how the significance of your research will benefit future studies, which is especially helpful for future researchers in your field. In the example of cyberbullying affecting student performance, your research could provide further opportunities to assess teacher perceptions of cyberbullying and its effects on students from larger populations. This prepares future researchers for data collection and analysis.

Discussing the significance of your research may sound daunting when you haven’t conducted it yet. However, an audience might not read your paper if they don’t know the significance of the research. By focusing on the problem statement and the research benefits to society and future studies, you can convince your audience of the value of your research.

Remember that everything you write doesn’t have to be set in stone. You can go back and tweak the significance of your research after conducting it. At first, you might only include general contributions of your study, but as you research, your contributions will become more specific.

You should have a solid understanding of your topic in general, its associated problems, and the literature review before tackling the significance of your research. However, you’re not trying to prove your thesis statement at this point. The significance of research just convinces the audience that your study is worth reading.

Finally, we always recommend seeking help from your research advisor whenever you’re struggling with ideas. For a more visual idea of how to discuss the significance of your research, we suggest checking out this video .

1. Do I need to do my research before discussing its significance?

No, you’re discussing the significance of your research before you conduct it. However, you should be knowledgeable about your topic and the related literature.

2. Is the significance of research the same as its implications?

No, the research implications are potential questions from your study that justify further exploration, which comes after conducting the research.

3. Discussing the significance of research seems overwhelming. Where should I start?

We recommend the problem statement as a starting point, which reveals clues to the potential outcome of your research.

4. How can I get feedback on my discussion of the significance of my research?

Our proofreading experts can help. They’ll check your writing for grammar, punctuation errors, spelling, and concision. Submit a 500-word document for free today!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

What is the Significance of a Study? Examples and Guide

If you’re reading this post you’re probably wondering: what is the significance of a study?

No matter where you’re at with a piece of research, it is a good idea to think about the potential significance of your work. And sometimes you’ll have to explicitly write a statement of significance in your papers, it addition to it forming part of your thesis.

In this post I’ll cover what the significance of a study is, how to measure it, how to describe it with examples and add in some of my own experiences having now worked in research for over nine years.

If you’re reading this because you’re writing up your first paper, welcome! You may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Looking for guidance on writing the statement of significance for a paper or thesis? Click here to skip straight to that section.

What is the Significance of a Study?

For research papers, theses or dissertations it’s common to explicitly write a section describing the significance of the study. We’ll come onto what to include in that section in just a moment.

However the significance of a study can actually refer to several different things.

Working our way from the most technical to the broadest, depending on the context, the significance of a study may refer to:

- Within your study: Statistical significance. Can we trust the findings?

- Wider research field: Research significance. How does your study progress the field?

- Commercial / economic significance: Could there be business opportunities for your findings?

- Societal significance: What impact could your study have on the wider society.

- And probably other domain-specific significance!

We’ll shortly cover each of them in turn, including how they’re measured and some examples for each type of study significance.

But first, let’s touch on why you should consider the significance of your research at an early stage.

Why Care About the Significance of a Study?

No matter what is motivating you to carry out your research, it is sensible to think about the potential significance of your work. In the broadest sense this asks, how does the study contribute to the world?

After all, for many people research is only worth doing if it will result in some expected significance. For the vast majority of us our studies won’t be significant enough to reach the evening news, but most studies will help to enhance knowledge in a particular field and when research has at least some significance it makes for a far more fulfilling longterm pursuit.

Furthermore, a lot of us are carrying out research funded by the public. It therefore makes sense to keep an eye on what benefits the work could bring to the wider community.

Often in research you’ll come to a crossroads where you must decide which path of research to pursue. Thinking about the potential benefits of a strand of research can be useful for deciding how to spend your time, money and resources.

It’s worth noting though, that not all research activities have to work towards obvious significance. This is especially true while you’re a PhD student, where you’re figuring out what you enjoy and may simply be looking for an opportunity to learn a new skill.

However, if you’re trying to decide between two potential projects, it can be useful to weigh up the potential significance of each.

Let’s now dive into the different types of significance, starting with research significance.

Research Significance

What is the research significance of a study.

Unless someone specifies which type of significance they’re referring to, it is fair to assume that they want to know about the research significance of your study.

Research significance describes how your work has contributed to the field, how it could inform future studies and progress research.

Where should I write about my study’s significance in my thesis?

Typically you should write about your study’s significance in the Introduction and Conclusions sections of your thesis.

It’s important to mention it in the Introduction so that the relevance of your work and the potential impact and benefits it could have on the field are immediately apparent. Explaining why your work matters will help to engage readers (and examiners!) early on.

It’s also a good idea to detail the study’s significance in your Conclusions section. This adds weight to your findings and helps explain what your study contributes to the field.

On occasion you may also choose to include a brief description in your Abstract.

What is expected when submitting an article to a journal

It is common for journals to request a statement of significance, although this can sometimes be called other things such as:

- Impact statement

- Significance statement

- Advances in knowledge section

Here is one such example of what is expected:

Impact Statement: An Impact Statement is required for all submissions. Your impact statement will be evaluated by the Editor-in-Chief, Global Editors, and appropriate Associate Editor. For your manuscript to receive full review, the editors must be convinced that it is an important advance in for the field. The Impact Statement is not a restating of the abstract. It should address the following: Why is the work submitted important to the field? How does the work submitted advance the field? What new information does this work impart to the field? How does this new information impact the field? Experimental Biology and Medicine journal, author guidelines

Typically the impact statement will be shorter than the Abstract, around 150 words.

Defining the study’s significance is helpful not just for the impact statement (if the journal asks for one) but also for building a more compelling argument throughout your submission. For instance, usually you’ll start the Discussion section of a paper by highlighting the research significance of your work. You’ll also include a short description in your Abstract too.

How to describe the research significance of a study, with examples

Whether you’re writing a thesis or a journal article, the approach to writing about the significance of a study are broadly the same.

I’d therefore suggest using the questions above as a starting point to base your statements on.

- Why is the work submitted important to the field?

- How does the work submitted advance the field?

- What new information does this work impart to the field?

- How does this new information impact the field?

Answer those questions and you’ll have a much clearer idea of the research significance of your work.

When describing it, try to clearly state what is novel about your study’s contribution to the literature. Then go on to discuss what impact it could have on progressing the field along with recommendations for future work.

Potential sentence starters

If you’re not sure where to start, why not set a 10 minute timer and have a go at trying to finish a few of the following sentences. Not sure on what to put? Have a chat to your supervisor or lab mates and they may be able to suggest some ideas.

- This study is important to the field because…

- These findings advance the field by…

- Our results highlight the importance of…

- Our discoveries impact the field by…

Now you’ve had a go let’s have a look at some real life examples.

Statement of significance examples

A statement of significance / impact:

Impact Statement This review highlights the historical development of the concept of “ideal protein” that began in the 1950s and 1980s for poultry and swine diets, respectively, and the major conceptual deficiencies of the long-standing concept of “ideal protein” in animal nutrition based on recent advances in amino acid (AA) metabolism and functions. Nutritionists should move beyond the “ideal protein” concept to consider optimum ratios and amounts of all proteinogenic AAs in animal foods and, in the case of carnivores, also taurine. This will help formulate effective low-protein diets for livestock, poultry, and fish, while sustaining global animal production. Because they are not only species of agricultural importance, but also useful models to study the biology and diseases of humans as well as companion (e.g. dogs and cats), zoo, and extinct animals in the world, our work applies to a more general readership than the nutritionists and producers of farm animals. Wu G, Li P. The “ideal protein” concept is not ideal in animal nutrition. Experimental Biology and Medicine . 2022;247(13):1191-1201. doi: 10.1177/15353702221082658

And the same type of section but this time called “Advances in knowledge”:

Advances in knowledge: According to the MY-RADs criteria, size measurements of focal lesions in MRI are now of relevance for response assessment in patients with monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Size changes of 1 or 2 mm are frequently observed due to uncertainty of the measurement only, while the actual focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Size changes of at least 6 mm or more in T 1 weighted or T 2 weighted short tau inversion recovery sequences occur in only 5% or less of cases when the focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Wennmann M, Grözinger M, Weru V, et al. Test-retest, inter- and intra-rater reproducibility of size measurements of focal bone marrow lesions in MRI in patients with multiple myeloma [published online ahead of print, 2023 Apr 12]. Br J Radiol . 2023;20220745. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220745

Other examples of research significance

Moving beyond the formal statement of significance, here is how you can describe research significance more broadly within your paper.

Describing research impact in an Abstract of a paper:

Three-dimensional visualisation and quantification of the chondrocyte population within articular cartilage can be achieved across a field of view of several millimetres using laboratory-based micro-CT. The ability to map chondrocytes in 3D opens possibilities for research in fields from skeletal development through to medical device design and treatment of cartilage degeneration. Conclusions section of the abstract in my first paper .

In the Discussion section of a paper:

We report for the utility of a standard laboratory micro-CT scanner to visualise and quantify features of the chondrocyte population within intact articular cartilage in 3D. This study represents a complimentary addition to the growing body of evidence supporting the non-destructive imaging of the constituents of articular cartilage. This offers researchers the opportunity to image chondrocyte distributions in 3D without specialised synchrotron equipment, enabling investigations such as chondrocyte morphology across grades of cartilage damage, 3D strain mapping techniques such as digital volume correlation to evaluate mechanical properties in situ , and models for 3D finite element analysis in silico simulations. This enables an objective quantification of chondrocyte distribution and morphology in three dimensions allowing greater insight for investigations into studies of cartilage development, degeneration and repair. One such application of our method, is as a means to provide a 3D pattern in the cartilage which, when combined with digital volume correlation, could determine 3D strain gradient measurements enabling potential treatment and repair of cartilage degeneration. Moreover, the method proposed here will allow evaluation of cartilage implanted with tissue engineered scaffolds designed to promote chondral repair, providing valuable insight into the induced regenerative process. The Discussion section of the paper is laced with references to research significance.

How is longer term research significance measured?

Looking beyond writing impact statements within papers, sometimes you’ll want to quantify the long term research significance of your work. For instance when applying for jobs.

The most obvious measure of a study’s long term research significance is the number of citations it receives from future publications. The thinking is that a study which receives more citations will have had more research impact, and therefore significance , than a study which received less citations. Citations can give a broad indication of how useful the work is to other researchers but citations aren’t really a good measure of significance.

Bear in mind that us researchers can be lazy folks and sometimes are simply looking to cite the first paper which backs up one of our claims. You can find studies which receive a lot of citations simply for packaging up the obvious in a form which can be easily found and referenced, for instance by having a catchy or optimised title.

Likewise, research activity varies wildly between fields. Therefore a certain study may have had a big impact on a particular field but receive a modest number of citations, simply because not many other researchers are working in the field.

Nevertheless, citations are a standard measure of significance and for better or worse it remains impressive for someone to be the first author of a publication receiving lots of citations.

Other measures for the research significance of a study include:

- Accolades: best paper awards at conferences, thesis awards, “most downloaded” titles for articles, press coverage.

- How much follow-on research the study creates. For instance, part of my PhD involved a novel material initially developed by another PhD student in the lab. That PhD student’s research had unlocked lots of potential new studies and now lots of people in the group were using the same material and developing it for different applications. The initial study may not receive a high number of citations yet long term it generated a lot of research activity.

That covers research significance, but you’ll often want to consider other types of significance for your study and we’ll cover those next.

Statistical Significance

What is the statistical significance of a study.

Often as part of a study you’ll carry out statistical tests and then state the statistical significance of your findings: think p-values eg <0.05. It is useful to describe the outcome of these tests within your report or paper, to give a measure of statistical significance.

Effectively you are trying to show whether the performance of your innovation is actually better than a control or baseline and not just chance. Statistical significance deserves a whole other post so I won’t go into a huge amount of depth here.

Things that make publication in The BMJ impossible or unlikely Internal validity/robustness of the study • It had insufficient statistical power, making interpretation difficult; • Lack of statistical power; The British Medical Journal’s guide for authors

Calculating statistical significance isn’t always necessary (or valid) for a study, such as if you have a very small number of samples, but it is a very common requirement for scientific articles.

Writing a journal article? Check the journal’s guide for authors to see what they expect. Generally if you have approximately five or more samples or replicates it makes sense to start thinking about statistical tests. Speak to your supervisor and lab mates for advice, and look at other published articles in your field.

How is statistical significance measured?

Statistical significance is quantified using p-values . Depending on your study design you’ll choose different statistical tests to compute the p-value.

A p-value of 0.05 is a common threshold value. The 0.05 means that there is a 1/20 chance that the difference in performance you’re reporting is just down to random chance.

- p-values above 0.05 mean that the result isn’t statistically significant enough to be trusted: it is too likely that the effect you’re showing is just luck.

- p-values less than or equal to 0.05 mean that the result is statistically significant. In other words: unlikely to just be chance, which is usually considered a good outcome.

Low p-values (eg p = 0.001) mean that it is highly unlikely to be random chance (1/1000 in the case of p = 0.001), therefore more statistically significant.

It is important to clarify that, although low p-values mean that your findings are statistically significant, it doesn’t automatically mean that the result is scientifically important. More on that in the next section on research significance.

How to describe the statistical significance of your study, with examples

In the first paper from my PhD I ran some statistical tests to see if different staining techniques (basically dyes) increased how well you could see cells in cow tissue using micro-CT scanning (a 3D imaging technique).

In your methods section you should mention the statistical tests you conducted and then in the results you will have statements such as:

Between mediums for the two scan protocols C/N [contrast to noise ratio] was greater for EtOH than the PBS in both scanning methods (both p < 0.0001) with mean differences of 1.243 (95% CI [confidence interval] 0.709 to 1.778) for absorption contrast and 6.231 (95% CI 5.772 to 6.690) for propagation contrast. … Two repeat propagation scans were taken of samples from the PTA-stained groups. No difference in mean C/N was found with either medium: PBS had a mean difference of 0.058 ( p = 0.852, 95% CI -0.560 to 0.676), EtOH had a mean difference of 1.183 ( p = 0.112, 95% CI 0.281 to 2.648). From the Results section of my first paper, available here . Square brackets added for this post to aid clarity.

From this text the reader can infer from the first paragraph that there was a statistically significant difference in using EtOH compared to PBS (really small p-value of <0.0001). However, from the second paragraph, the difference between two repeat scans was statistically insignificant for both PBS (p = 0.852) and EtOH (p = 0.112).

By conducting these statistical tests you have then earned your right to make bold statements, such as these from the discussion section:

Propagation phase-contrast increases the contrast of individual chondrocytes [cartilage cells] compared to using absorption contrast. From the Discussion section from the same paper.

Without statistical tests you have no evidence that your results are not just down to random chance.

Beyond describing the statistical significance of a study in the main body text of your work, you can also show it in your figures.

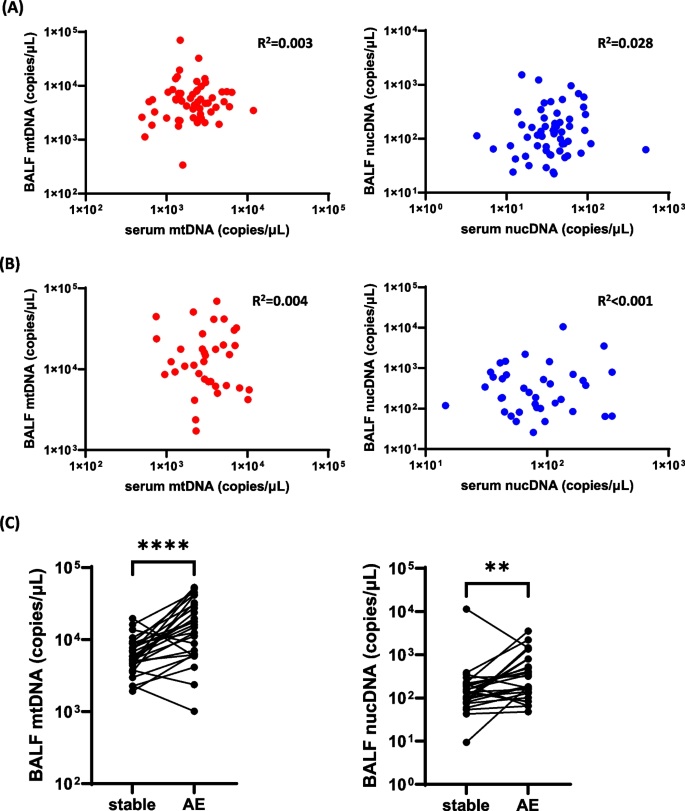

In figures such as bar charts you’ll often see asterisks to represent statistical significance, and “n.s.” to show differences between groups which are not statistically significant. Here is one such figure, with some subplots, from the same paper:

In this example an asterisk (*) between two bars represents p < 0.05. Two asterisks (**) represents p < 0.001 and three asterisks (***) represents p < 0.0001. This should always be stated in the caption of your figure since the values that each asterisk refers to can vary.

Now that we know if a study is showing statistically and research significance, let’s zoom out a little and consider the potential for commercial significance.

Commercial and Industrial Significance

What are commercial and industrial significance.

Moving beyond significance in relation to academia, your research may also have commercial or economic significance.

Simply put:

- Commercial significance: could the research be commercialised as a product or service? Perhaps the underlying technology described in your study could be licensed to a company or you could even start your own business using it.

- Industrial significance: more widely than just providing a product which could be sold, does your research provide insights which may affect a whole industry? Such as: revealing insights or issues with current practices, performance gains you don’t want to commercialise (e.g. solar power efficiency), providing suggested frameworks or improvements which could be employed industry-wide.

I’ve grouped these two together because there can certainly be overlap. For instance, perhaps your new technology could be commercialised whilst providing wider improvements for the whole industry.

Commercial and industrial significance are not relevant to most studies, so only write about it if you and your supervisor can think of reasonable routes to your work having an impact in these ways.

How are commercial and industrial significance measured?

Unlike statistical and research significances, the measures of commercial and industrial significance can be much more broad.

Here are some potential measures of significance:

Commercial significance:

- How much value does your technology bring to potential customers or users?

- How big is the potential market and how much revenue could the product potentially generate?

- Is the intellectual property protectable? i.e. patentable, or if not could the novelty be protected with trade secrets: if so publish your method with caution!

- If commercialised, could the product bring employment to a geographical area?

Industrial significance:

What impact could it have on the industry? For instance if you’re revealing an issue with something, such as unintended negative consequences of a drug , what does that mean for the industry and the public? This could be:

- Reduced overhead costs

- Better safety

- Faster production methods

- Improved scaleability

How to describe the commercial and industrial significance of a study, with examples

Commercial significance.

If your technology could be commercially viable, and you’ve got an interest in commercialising it yourself, it is likely that you and your university may not want to immediately publish the study in a journal.

You’ll probably want to consider routes to exploiting the technology and your university may have a “technology transfer” team to help researchers navigate the various options.

However, if instead of publishing a paper you’re submitting a thesis or dissertation then it can be useful to highlight the commercial significance of your work. In this instance you could include statements of commercial significance such as:

The measurement technology described in this study provides state of the art performance and could enable the development of low cost devices for aerospace applications. An example of commercial significance I invented for this post

Industrial significance

First, think about the industrial sectors who could benefit from the developments described in your study.

For example if you’re working to improve battery efficiency it is easy to think of how it could lead to performance gains for certain industries, like personal electronics or electric vehicles. In these instances you can describe the industrial significance relatively easily, based off your findings.

For example:

By utilising abundant materials in the described battery fabrication process we provide a framework for battery manufacturers to reduce dependence on rare earth components. Again, an invented example

For other technologies there may well be industrial applications but they are less immediately obvious and applicable. In these scenarios the best you can do is to simply reframe your research significance statement in terms of potential commercial applications in a broad way.

As a reminder: not all studies should address industrial significance, so don’t try to invent applications just for the sake of it!

Societal Significance

What is the societal significance of a study.

The most broad category of significance is the societal impact which could stem from it.

If you’re working in an applied field it may be quite easy to see a route for your research to impact society. For others, the route to societal significance may be less immediate or clear.

Studies can help with big issues facing society such as:

- Medical applications : vaccines, surgical implants, drugs, improving patient safety. For instance this medical device and drug combination I worked on which has a very direct route to societal significance.

- Political significance : Your research may provide insights which could contribute towards potential changes in policy or better understanding of issues facing society.

- Public health : for instance COVID-19 transmission and related decisions.

- Climate change : mitigation such as more efficient solar panels and lower cost battery solutions, and studying required adaptation efforts and technologies. Also, better understanding around related societal issues, for instance this study on the effects of temperature on hate speech.

How is societal significance measured?

Societal significance at a high level can be quantified by the size of its potential societal effect. Just like a lab risk assessment, you can think of it in terms of probability (or how many people it could help) and impact magnitude.

Societal impact = How many people it could help x the magnitude of the impact

Think about how widely applicable the findings are: for instance does it affect only certain people? Then think about the potential size of the impact: what kind of difference could it make to those people?

Between these two metrics you can get a pretty good overview of the potential societal significance of your research study.

How to describe the societal significance of a study, with examples

Quite often the broad societal significance of your study is what you’re setting the scene for in your Introduction. In addition to describing the existing literature, it is common to for the study’s motivation to touch on its wider impact for society.

For those of us working in healthcare research it is usually pretty easy to see a path towards societal significance.

Our CLOUT model has state-of-the-art performance in mortality prediction, surpassing other competitive NN models and a logistic regression model … Our results show that the risk factors identified by the CLOUT model agree with physicians’ assessment, suggesting that CLOUT could be used in real-world clinicalsettings. Our results strongly support that CLOUT may be a useful tool to generate clinical prediction models, especially among hospitalized and critically ill patient populations. Learning Latent Space Representations to Predict Patient Outcomes: Model Development and Validation

In other domains the societal significance may either take longer or be more indirect, meaning that it can be more difficult to describe the societal impact.

Even so, here are some examples I’ve found from studies in non-healthcare domains:

We examined food waste as an initial investigation and test of this methodology, and there is clear potential for the examination of not only other policy texts related to food waste (e.g., liability protection, tax incentives, etc.; Broad Leib et al., 2020) but related to sustainable fishing (Worm et al., 2006) and energy use (Hawken, 2017). These other areas are of obvious relevance to climate change… AI-Based Text Analysis for Evaluating Food Waste Policies

The continued development of state-of-the art NLP tools tailored to climate policy will allow climate researchers and policy makers to extract meaningful information from this growing body of text, to monitor trends over time and administrative units, and to identify potential policy improvements. BERT Classification of Paris Agreement Climate Action Plans

Top Tips For Identifying & Writing About the Significance of Your Study

- Writing a thesis? Describe the significance of your study in the Introduction and the Conclusion .

- Submitting a paper? Read the journal’s guidelines. If you’re writing a statement of significance for a journal, make sure you read any guidance they give for what they’re expecting.

- Take a step back from your research and consider your study’s main contributions.

- Read previously published studies in your field . Use this for inspiration and ideas on how to describe the significance of your own study

- Discuss the study with your supervisor and potential co-authors or collaborators and brainstorm potential types of significance for it.

Now you’ve finished reading up on the significance of a study you may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Writing an academic journal paper

I hope that you’ve learned something useful from this article about the significance of a study. If you have any more research-related questions let me know, I’m here to help.

To gain access to my content library you can subscribe below for free:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

Related Posts

How to Master Data Management in Research

25th April 2024 27th April 2024

Thesis Title: Examples and Suggestions from a PhD Grad

23rd February 2024 23rd February 2024

How to Stay Healthy as a Student

25th January 2024 25th January 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

How To Write a Significance Statement for Your Research

A significance statement is an essential part of a research paper. It explains the importance and relevance of the study to the academic community and the world at large. To write a compelling significance statement, identify the research problem, explain why it is significant, provide evidence of its importance, and highlight its potential impact on future research, policy, or practice. A well-crafted significance statement should effectively communicate the value of the research to readers and help them understand why it matters.

Updated on May 4, 2023

A significance statement is a clearly stated, non-technical paragraph that explains why your research matters. It’s central in making the public aware of and gaining support for your research.

Write it in jargon-free language that a reader from any field can understand. Well-crafted, easily readable significance statements can improve your chances for citation and impact and make it easier for readers outside your field to find and understand your work.

Read on for more details on what a significance statement is, how it can enhance the impact of your research, and, of course, how to write one.

What is a significance statement in research?

A significance statement answers the question: How will your research advance scientific knowledge and impact society at large (as well as specific populations)?

You might also see it called a “Significance of the study” statement. Some professional organizations in the STEM sciences and social sciences now recommended that journals in their disciplines make such statements a standard feature of each published article. Funding agencies also consider “significance” a key criterion for their awards.

Read some examples of significance statements from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) here .

Depending upon the specific journal or funding agency’s requirements, your statement may be around 100 words and answer these questions:

1. What’s the purpose of this research?

2. What are its key findings?

3. Why do they matter?

4. Who benefits from the research results?

Readers will want to know: “What is interesting or important about this research?” Keep asking yourself that question.

Where to place the significance statement in your manuscript

Most journals ask you to place the significance statement before or after the abstract, so check with each journal’s guide.

This article is focused on the formal significance statement, even though you’ll naturally highlight your project’s significance elsewhere in your manuscript. (In the introduction, you’ll set out your research aims, and in the conclusion, you’ll explain the potential applications of your research and recommend areas for future research. You’re building an overall case for the value of your work.)

Developing the significance statement

The main steps in planning and developing your statement are to assess the gaps to which your study contributes, and then define your work’s implications and impact.

Identify what gaps your study fills and what it contributes

Your literature review was a big part of how you planned your study. To develop your research aims and objectives, you identified gaps or unanswered questions in the preceding research and designed your study to address them.

Go back to that lit review and look at those gaps again. Review your research proposal to refresh your memory. Ask:

- How have my research findings advanced knowledge or provided notable new insights?

- How has my research helped to prove (or disprove) a hypothesis or answer a research question?

- Why are those results important?

Consider your study’s potential impact at two levels:

- What contribution does my research make to my field?

- How does it specifically contribute to knowledge; that is, who will benefit the most from it?

Define the implications and potential impact

As you make notes, keep the reasons in mind for why you are writing this statement. Whom will it impact, and why?

The first audience for your significance statement will be journal reviewers when you submit your article for publishing. Many journals require one for manuscript submissions. Study the author’s guide of your desired journal to see its criteria ( here’s an example ). Peer reviewers who can clearly understand the value of your research will be more likely to recommend publication.

Second, when you apply for funding, your significance statement will help justify why your research deserves a grant from a funding agency . The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), for example, wants to see that a project will “exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved.” Clear, simple language is always valuable because not all reviewers will be specialists in your field.

Third, this concise statement about your study’s importance can affect how potential readers engage with your work. Science journalists and interested readers can promote and spread your work, enhancing your reputation and influence. Help them understand your work.

You’re now ready to express the importance of your research clearly and concisely. Time to start writing.

How to write a significance statement: Key elements

When drafting your statement, focus on both the content and writing style.

- In terms of content, emphasize the importance, timeliness, and relevance of your research results.

- Write the statement in plain, clear language rather than scientific or technical jargon. Your audience will include not just your fellow scientists but also non-specialists like journalists, funding reviewers, and members of the public.

Follow the process we outline below to build a solid, well-crafted, and informative statement.

Get started

Some suggested opening lines to help you get started might be:

- The implications of this study are…

- Building upon previous contributions, our study moves the field forward because…

- Our study furthers previous understanding about…

Alternatively, you may start with a statement about the phenomenon you’re studying, leading to the problem statement.

Include these components

Next, draft some sentences that include the following elements. A good example, which we’ll use here, is a significance statement by Rogers et al. (2022) published in the Journal of Climate .

1. Briefly situate your research study in its larger context . Start by introducing the topic, leading to a problem statement. Here’s an example:

‘Heatwaves pose a major threat to human health, ecosystems, and human systems.”

2. State the research problem.

“Simultaneous heatwaves affecting multiple regions can exacerbate such threats. For example, multiple food-producing regions simultaneously undergoing heat-related crop damage could drive global food shortages.”

3. Tell what your study does to address it.

“We assess recent changes in the occurrence of simultaneous large heatwaves.”

4. Provide brief but powerful evidence to support the claims your statement is making , Use quantifiable terms rather than vague ones (e.g., instead of “This phenomenon is happening now more than ever,” see below how Rogers et al. (2022) explained it). This evidence intensifies and illustrates the problem more vividly:

“Such simultaneous heatwaves are 7 times more likely now than 40 years ago. They are also hotter and affect a larger area. Their increasing occurrence is mainly driven by warming baseline temperatures due to global heating, but changes in weather patterns contribute to disproportionate increases over parts of Europe, the eastern United States, and Asia.

5. Relate your study’s impact to the broader context , starting with its general significance to society—then, when possible, move to the particular as you name specific applications of your research findings. (Our example lacks this second level of application.)

“Better understanding the drivers of weather pattern changes is therefore important for understanding future concurrent heatwave characteristics and their impacts.”

Refine your English

Don’t understate or overstate your findings – just make clear what your study contributes. When you have all the elements in place, review your draft to simplify and polish your language. Even better, get an expert AJE edit . Be sure to use “plain” language rather than academic jargon.

- Avoid acronyms, scientific jargon, and technical terms

- Use active verbs in your sentence structure rather than passive voice (e.g., instead of “It was found that...”, use “We found...”)

- Make sentence structures short, easy to understand – readable

- Try to address only one idea in each sentence and keep sentences within 25 words (15 words is even better)

- Eliminate nonessential words and phrases (“fluff” and wordiness)

Enhance your significance statement’s impact

Always take time to review your draft multiple times. Make sure that you:

- Keep your language focused

- Provide evidence to support your claims

- Relate the significance to the broader research context in your field

After revising your significance statement, request feedback from a reading mentor about how to make it even clearer. If you’re not a native English speaker, seek help from a native-English-speaking colleague or use an editing service like AJE to make sure your work is at a native level.

Understanding the significance of your study

Your readers may have much less interest than you do in the specific details of your research methods and measures. Many readers will scan your article to learn how your findings might apply to them and their own research.

Different types of significance

Your findings may have different types of significance, relevant to different populations or fields of study for different reasons. You can emphasize your work’s statistical, clinical, or practical significance. Editors or reviewers in the social sciences might also evaluate your work’s social or political significance.

Statistical significance means that the results are unlikely to have occurred randomly. Instead, it implies a true cause-and-effect relationship.

Clinical significance means that your findings are applicable for treating patients and improving quality of life.

Practical significance is when your research outcomes are meaningful to society at large, in the “real world.” Practical significance is usually measured by the study’s effect size . Similarly, evaluators may attribute social or political significance to research that addresses “real and immediate” social problems.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is the Significance of the Study?

- By DiscoverPhDs

- August 25, 2020

- what the significance of the study means,

- why it’s important to include in your research work,

- where you would include it in your paper, thesis or dissertation,

- how you write one

- and finally an example of a well written section about the significance of the study.

What does Significance of the Study mean?

The significance of the study is a written statement that explains why your research was needed. It’s a justification of the importance of your work and impact it has on your research field, it’s contribution to new knowledge and how others will benefit from it.

Why is the Significance of the Study important?

The significance of the study, also known as the rationale of the study, is important to convey to the reader why the research work was important. This may be an academic reviewer assessing your manuscript under peer-review, an examiner reading your PhD thesis, a funder reading your grant application or another research group reading your published journal paper. Your academic writing should make clear to the reader what the significance of the research that you performed was, the contribution you made and the benefits of it.

How do you write the Significance of the Study?

When writing this section, first think about where the gaps in knowledge are in your research field. What are the areas that are poorly understood with little or no previously published literature? Or what topics have others previously published on that still require further work. This is often referred to as the problem statement.

The introduction section within the significance of the study should include you writing the problem statement and explaining to the reader where the gap in literature is.

Then think about the significance of your research and thesis study from two perspectives: (1) what is the general contribution of your research on your field and (2) what specific contribution have you made to the knowledge and who does this benefit the most.

For example, the gap in knowledge may be that the benefits of dumbbell exercises for patients recovering from a broken arm are not fully understood. You may have performed a study investigating the impact of dumbbell training in patients with fractures versus those that did not perform dumbbell exercises and shown there to be a benefit in their use. The broad significance of the study would be the improvement in the understanding of effective physiotherapy methods. Your specific contribution has been to show a significant improvement in the rate of recovery in patients with broken arms when performing certain dumbbell exercise routines.

This statement should be no more than 500 words in length when written for a thesis. Within a research paper, the statement should be shorter and around 200 words at most.

Significance of the Study: An example

Building on the above hypothetical academic study, the following is an example of a full statement of the significance of the study for you to consider when writing your own. Keep in mind though that there’s no single way of writing the perfect significance statement and it may well depend on the subject area and the study content.

Here’s another example to help demonstrate how a significance of the study can also be applied to non-technical fields:

The significance of this research lies in its potential to inform clinical practices and patient counseling. By understanding the psychological outcomes associated with non-surgical facial aesthetics, practitioners can better guide their patients in making informed decisions about their treatment plans. Additionally, this study contributes to the body of academic knowledge by providing empirical evidence on the effects of these cosmetic procedures, which have been largely anecdotal up to this point.

The statement of the significance of the study is used by students and researchers in academic writing to convey the importance of the research performed; this section is written at the end of the introduction and should describe the specific contribution made and who it benefits.

Need to write a list of abbreviations for a thesis or dissertation? Read our post to find out where they go, what to include and how to format them.

Starting your PhD can feel like a daunting, exciting and special time. They’ll be so much to think about – here are a few tips to help you get started.

Multistage sampling is a more complex form of cluster sampling for obtaining sample populations. Learn their pros and cons and how to undertake them.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

The unit of analysis refers to the main parameter that you’re investigating in your research project or study.

The purpose of research is to enhance society by advancing knowledge through developing scientific theories, concepts and ideas – find out more on what this involves.

Kai is a PhD student at Imperial College London. His research centres around sample efficiency, transfer learning and interpretability for deep reinforcement learning.

Dr Manning gained his PhD in Chemical Engineering from the University of Sheffield in 2019. He is now a postdoc researcher studying molecular simulations on nanomaterials at the University of Bath.

Join Thousands of Students

How To Write Significance of the Study (With Examples)

Whether you’re writing a research paper or thesis, a portion called Significance of the Study ensures your readers understand the impact of your work. Learn how to effectively write this vital part of your research paper or thesis through our detailed steps, guidelines, and examples.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

What is the significance of the study.

The Significance of the Study presents the importance of your research. It allows you to prove the study’s impact on your field of research, the new knowledge it contributes, and the people who will benefit from it.

Related: How To Write Scope and Delimitation of a Research Paper (With Examples)

Where Should I Put the Significance of the Study?

The Significance of the Study is part of the first chapter or the Introduction. It comes after the research’s rationale, problem statement, and hypothesis.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Why Should I Include the Significance of the Study?

The purpose of the Significance of the Study is to give you space to explain to your readers how exactly your research will be contributing to the literature of the field you are studying 1 . It’s where you explain why your research is worth conducting and its significance to the community, the people, and various institutions.

How To Write Significance of the Study: 5 Steps

Below are the steps and guidelines for writing your research’s Significance of the Study.

1. Use Your Research Problem as a Starting Point

Your problem statement can provide clues to your research study’s outcome and who will benefit from it 2 .

Ask yourself, “How will the answers to my research problem be beneficial?”. In this manner, you will know how valuable it is to conduct your study.

Let’s say your research problem is “What is the level of effectiveness of the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in lowering the blood glucose level of Swiss mice (Mus musculus)?”

Discovering a positive correlation between the use of lemongrass and lower blood glucose level may lead to the following results:

- Increased public understanding of the plant’s medical properties;

- Higher appreciation of the importance of lemongrass by the community;

- Adoption of lemongrass tea as a cheap, readily available, and natural remedy to lower their blood glucose level.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the general benefits of your study, it’s time to break it down into specific beneficiaries.

2. State How Your Research Will Contribute to the Existing Literature in the Field

Think of the things that were not explored by previous studies. Then, write how your research tackles those unexplored areas. Through this, you can convince your readers that you are studying something new and adding value to the field.

3. Explain How Your Research Will Benefit Society

In this part, tell how your research will impact society. Think of how the results of your study will change something in your community.

For example, in the study about using lemongrass tea to lower blood glucose levels, you may indicate that through your research, the community will realize the significance of lemongrass and other herbal plants. As a result, the community will be encouraged to promote the cultivation and use of medicinal plants.

4. Mention the Specific Persons or Institutions Who Will Benefit From Your Study

Using the same example above, you may indicate that this research’s results will benefit those seeking an alternative supplement to prevent high blood glucose levels.

5. Indicate How Your Study May Help Future Studies in the Field

You must also specifically indicate how your research will be part of the literature of your field and how it will benefit future researchers. In our example above, you may indicate that through the data and analysis your research will provide, future researchers may explore other capabilities of herbal plants in preventing different diseases.

Tips and Warnings

- Think ahead . By visualizing your study in its complete form, it will be easier for you to connect the dots and identify the beneficiaries of your research.

- Write concisely. Make it straightforward, clear, and easy to understand so that the readers will appreciate the benefits of your research. Avoid making it too long and wordy.

- Go from general to specific . Like an inverted pyramid, you start from above by discussing the general contribution of your study and become more specific as you go along. For instance, if your research is about the effect of remote learning setup on the mental health of college students of a specific university , you may start by discussing the benefits of the research to society, to the educational institution, to the learning facilitators, and finally, to the students.

- Seek help . For example, you may ask your research adviser for insights on how your research may contribute to the existing literature. If you ask the right questions, your research adviser can point you in the right direction.

- Revise, revise, revise. Be ready to apply necessary changes to your research on the fly. Unexpected things require adaptability, whether it’s the respondents or variables involved in your study. There’s always room for improvement, so never assume your work is done until you have reached the finish line.

Significance of the Study Examples

This section presents examples of the Significance of the Study using the steps and guidelines presented above.

Example 1: STEM-Related Research

Research Topic: Level of Effectiveness of the Lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ) Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice ( Mus musculus ).

Significance of the Study .

This research will provide new insights into the medicinal benefit of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ), specifically on its hypoglycemic ability.

Through this research, the community will further realize promoting medicinal plants, especially lemongrass, as a preventive measure against various diseases. People and medical institutions may also consider lemongrass tea as an alternative supplement against hyperglycemia.

Moreover, the analysis presented in this study will convey valuable information for future research exploring the medicinal benefits of lemongrass and other medicinal plants.

Example 2: Business and Management-Related Research

Research Topic: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Social Media Marketing of Small Clothing Enterprises.

Significance of the Study:

By comparing the two marketing strategies presented by this research, there will be an expansion on the current understanding of the firms on these marketing strategies in terms of cost, acceptability, and sustainability. This study presents these marketing strategies for small clothing enterprises, giving them insights into which method is more appropriate and valuable for them.

Specifically, this research will benefit start-up clothing enterprises in deciding which marketing strategy they should employ. Long-time clothing enterprises may also consider the result of this research to review their current marketing strategy.

Furthermore, a detailed presentation on the comparison of the marketing strategies involved in this research may serve as a tool for further studies to innovate the current method employed in the clothing Industry.

Example 3: Social Science -Related Research.

Research Topic: Divide Et Impera : An Overview of How the Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Prevailed on Philippine Political History.

Significance of the Study :

Through the comprehensive exploration of this study on Philippine political history, the influence of the Divide et Impera, or political decentralization, on the political discernment across the history of the Philippines will be unraveled, emphasized, and scrutinized. Moreover, this research will elucidate how this principle prevailed until the current political theatre of the Philippines.

In this regard, this study will give awareness to society on how this principle might affect the current political context. Moreover, through the analysis made by this study, political entities and institutions will have a new approach to how to deal with this principle by learning about its influence in the past.

In addition, the overview presented in this research will push for new paradigms, which will be helpful for future discussion of the Divide et Impera principle and may lead to a more in-depth analysis.

Example 4: Humanities-Related Research

Research Topic: Effectiveness of Meditation on Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students.

Significance of the Study:

This research will provide new perspectives in approaching anxiety issues of college students through meditation.

Specifically, this research will benefit the following:

Community – this study spreads awareness on recognizing anxiety as a mental health concern and how meditation can be a valuable approach to alleviating it.

Academic Institutions and Administrators – through this research, educational institutions and administrators may promote programs and advocacies regarding meditation to help students deal with their anxiety issues.

Mental health advocates – the result of this research will provide valuable information for the advocates to further their campaign on spreading awareness on dealing with various mental health issues, including anxiety, and how to stop stigmatizing those with mental health disorders.

Parents – this research may convince parents to consider programs involving meditation that may help the students deal with their anxiety issues.

Students will benefit directly from this research as its findings may encourage them to consider meditation to lower anxiety levels.

Future researchers – this study covers information involving meditation as an approach to reducing anxiety levels. Thus, the result of this study can be used for future discussions on the capabilities of meditation in alleviating other mental health concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is the difference between the significance of the study and the rationale of the study.

Both aim to justify the conduct of the research. However, the Significance of the Study focuses on the specific benefits of your research in the field, society, and various people and institutions. On the other hand, the Rationale of the Study gives context on why the researcher initiated the conduct of the study.

Let’s take the research about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Levels of College Students as an example. Suppose you are writing about the Significance of the Study. In that case, you must explain how your research will help society, the academic institution, and students deal with anxiety issues through meditation. Meanwhile, for the Rationale of the Study, you may state that due to the prevalence of anxiety attacks among college students, you’ve decided to make it the focal point of your research work.

2. What is the difference between Justification and the Significance of the Study?

In Justification, you express the logical reasoning behind the conduct of the study. On the other hand, the Significance of the Study aims to present to your readers the specific benefits your research will contribute to the field you are studying, community, people, and institutions.

Suppose again that your research is about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students. Suppose you are writing the Significance of the Study. In that case, you may state that your research will provide new insights and evidence regarding meditation’s ability to reduce college students’ anxiety levels. Meanwhile, you may note in the Justification that studies are saying how people used meditation in dealing with their mental health concerns. You may also indicate how meditation is a feasible approach to managing anxiety using the analysis presented by previous literature.

3. How should I start my research’s Significance of the Study section?

– This research will contribute… – The findings of this research… – This study aims to… – This study will provide… – Through the analysis presented in this study… – This study will benefit…

Moreover, you may start the Significance of the Study by elaborating on the contribution of your research in the field you are studying.

4. What is the difference between the Purpose of the Study and the Significance of the Study?

The Purpose of the Study focuses on why your research was conducted, while the Significance of the Study tells how the results of your research will benefit anyone.

Suppose your research is about the Effectiveness of Lemongrass Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice . You may include in your Significance of the Study that the research results will provide new information and analysis on the medical ability of lemongrass to solve hyperglycemia. Meanwhile, you may include in your Purpose of the Study that your research wants to provide a cheaper and natural way to lower blood glucose levels since commercial supplements are expensive.

5. What is the Significance of the Study in Tagalog?

In Filipino research, the Significance of the Study is referred to as Kahalagahan ng Pag-aaral.

- Draft your Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from http://dissertationedd.usc.edu/draft-your-significance-of-the-study.html

- Regoniel, P. (2015). Two Tips on How to Write the Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from https://simplyeducate.me/2015/02/09/significance-of-the-study/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE : A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration: