- AI Essay Writer

- Paraphraser

- AI Text Summarizer

- AI Research Tool

- AI PDF Summarizer

- Outline Generator

- Essay Grader

- Essay Checker

If you ever wondered about how to critique something, a book, a film, or maybe even a research hypothesis, then the answer for you is – to write a critical essay about it. This type of writing revolves around the deep evaluation of the material in front of you. So, in such papers, the goal isn’t to say whether you liked something or not, but rather to analyze it based on evidence and logic. Think of it as taking a step back and asking, “What is really going on here?” and “How did the creator make that happen?”

In a critical essay, you start with a central claim or thesis that makes an argument about the material you’re analyzing. From there, you’ll support your points using evidence, like specific quotes from a book or scenes from a movie. And unlike casual conversations, this type of writing avoids personal opinions or judgments like “I liked it” or “It was boring.” Instead, you’re focused on breaking down the details and exploring themes, techniques, or strategies used by the creator.

For example, rather than saying “Charlie was so lucky to find a Golden Ticket” after watching Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, a critical essay might explore how the film uses the contrast between wealth and morality to make a statement about society.

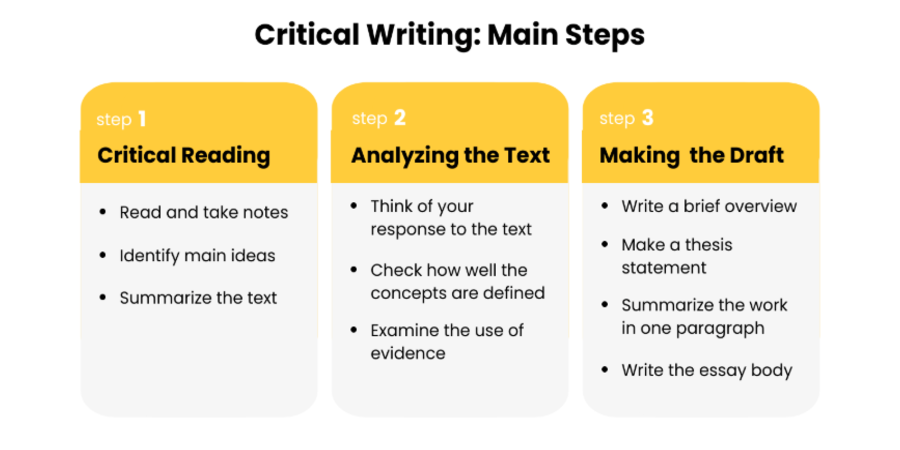

Writing a Perfect Critical Essay: Here’s What to Do

Writing a critical essay doesn’t have to be overwhelming if you approach it with a solid plan. Here’s a step-by-step breakdown of how you can structure your writing process to create a thoughtful, well-organized essay that impresses your readers (and earns you those high grades).

Choose and Fully Understand Your Topic

First things first—you need to select something to write about. This can be a movie, book, piece of music, or artwork. Just make sure it’s something you’re interested in and that you understand well. If your topic is assigned, spend time getting familiar with it. Watch the film or read the book a couple of times, and take notes on key themes, techniques, or elements that stand out.

Gather Your Sources

You’ll need evidence to support your analysis, so gather relevant material. Use scholarly sources like journal articles, books, and credible websites to back up your claims. The trick here is not just collecting information but understanding it. As such, if you’re writing about a novel, find analyses that discuss the author’s themes or techniques, and use that to build your argument. And remember to always keep track of your sources for proper citations later!

Develop a Strong Thesis Statement

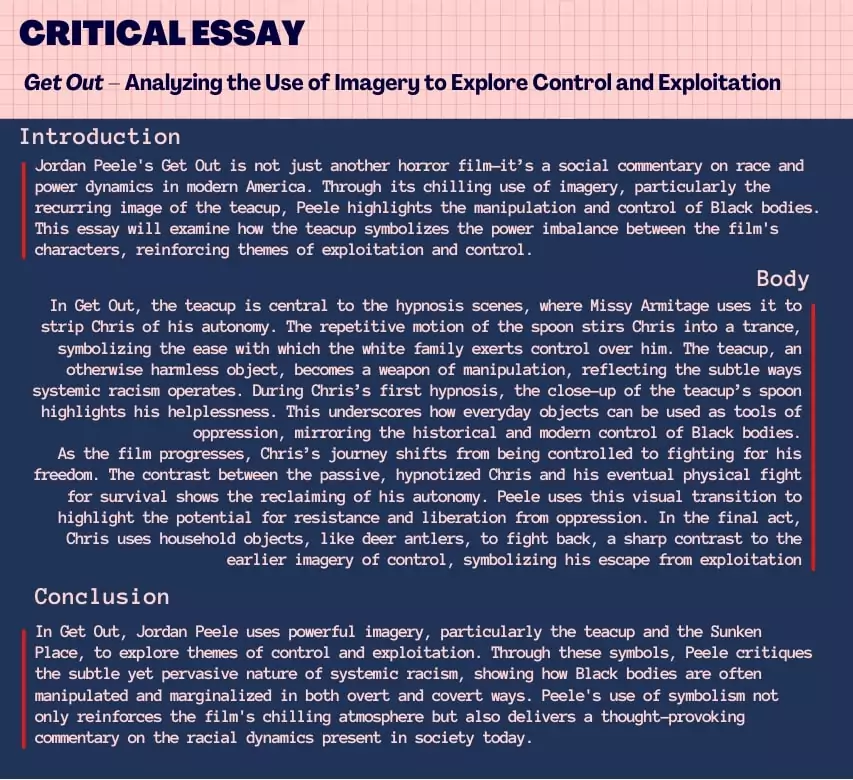

Once you’ve done your research, it’s time to craft your thesis statement. This is the central argument of your essay, and everything you write should connect back to it. For example, if you’re analyzing the use of imagery in Get Out , your thesis might argue how the recurring image of the teacup symbolizes the control and manipulation of Black bodies in the film, reinforcing themes of power and exploitation. Keep your thesis specific, focused, and arguable ad it will carry your entire essay.

Create an Outline

Before you start writing, create an outline to organize your ideas. A typical critical essay includes an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. In the body, each paragraph should focus on a different point that supports your thesis. For instance, one paragraph might discuss symbolism, another might analyze character development, and a third could cover narrative techniques. Outlining helps you see the flow of your writing and make sure that each point has enough evidence to back it up.

Write the Body Paragraphs First

With your outline in place, begin writing the body paragraphs. Each paragraph should start with a topic sentence that introduces the main point, followed by evidence (quotes, examples, or facts) to support it. After presenting the evidence, analyze it and explain how it ties into your thesis. If you’re analyzing a movie, for example, you might focus one paragraph on how the director uses camera angles to create tension in a scene. Stay focused and make sure everything ties back to your central argument.

Write the Conclusion

After finishing the body paragraphs, write the conclusion. This is where you sum up the key points of your essay and restate your thesis in light of the evidence you’ve presented. The conclusion should not introduce new information but instead reinforce your argument, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of your analysis.

Write the Introduction Last

Now that you’ve got the bulk of the essay written, it’s time to finally build the introduction. Start with a hook to grab the reader’s attention—a bold statement, an intriguing question, or a surprising fact can work well. Then, provide some background information to set the context for your analysis, and finish with your thesis statement that you have already created. Writing the introduction last allows you to make sure it aligns perfectly with the rest of your essay and clearly presents your argument.

Revise, Edit, and Proofread

You’ve got your first draft—congrats! Now, it’s time to bring it to perfection. Read through your essay a few times to improve clarity and flow. Check if all your points are well-supported and if your argument makes sense from start to finish. Edit for grammar, spelling, and style errors, and make sure all citations are correctly formatted. Taking this step seriously can make a huge difference in the overall quality of your essay (and in your grade as well).

Critical Essay Example: Proper Structure & Outline

Now, if you still feel kind of lost in all this information, don’t worry too much. Below you will find an example of what a well-organized critical essay can look like. Check it out to gain some inspiration and you will definitely be able to jump right into the writing process in no time at all.

How should I start a critical essay?

To start a critical essay, begin with an engaging introduction that grabs the reader’s attention. You can use a hook, such as an interesting fact, a bold statement, or even a thought-provoking question. After the hook, provide some background information on the topic you’re discussing to set the stage. Finally, end the introduction with a clear thesis statement outlining the main argument or point you’ll analyze. This thesis will guide your essay and tell readers what to expect from your analysis.

What is a critical essay and example?

A critical essay is a type of writing where you analyze and evaluate a piece of work, such as a book, film, painting, or even a theory. This type of writing is dedicated to exploring the deeper meanings, strengths, weaknesses, and overall impact of its subject. For example, if you’re writing a critical essay about The Great Gatsby, you wouldn’t just summarize the plot—you’d dive into how F. Scott Fitzgerald uses symbolism and themes like the American Dream to convey larger messages.

What is the layout of a critical essay?

The layout of a critical essay usually follows a standard structure: an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. In the introduction, you present the topic and your thesis. The body paragraphs are where you break down the main points of your analysis, using evidence to support your claims. The conclusion ties everything together, summarizing your key points and restating your thesis in light of the evidence you’ve discussed.

What are the parts of a critical essay?

A critical essay has three main parts: the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

- Introduction : This is where you introduce the work you’re analyzing and present your thesis.

- Body Paragraphs : These are the meat of your essay, where you break down your analysis into different points, using evidence and examples to support your arguments.

- Conclusion : Here, you wrap up your analysis, summarizing the main points and reinforcing how they support your thesis.

Related Posts

How to Write an Evaluation Essay

- October 3, 2024

- Comments Off on How to Write an Evaluation Essay

How to Quote a Poem in an Essay

- September 27, 2024

- Comments Off on How to Quote a Poem in an Essay

How to Write a Profile Essay

- Comments Off on How to Write a Profile Essay

Are you ready to write top-quality essays?

Boost Your Essay Writing Skills and Achievements with Textero AI

- No credit card required to start

- Cancel anytime

- 4 different tools to explore

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

An Essay on Criticism Summary & Analysis by Alexander Pope

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

Alexander Pope's "An Essay on Criticism" seeks to lay down rules of good taste in poetry criticism, and in poetry itself. Structured as an essay in rhyming verse, it offers advice to the aspiring critic while satirizing amateurish criticism and poetry. The famous passage beginning "A little learning is a dangerous thing" advises would-be critics to learn their field in depth, warning that the arts demand much longer and more arduous study than beginners expect. The passage can also be read as a warning against shallow learning in general. Published in 1711, when Alexander Pope was just 23, the "Essay" brought its author fame and notoriety while he was still a young poet himself.

- Read the full text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

The Full Text of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

1 A little learning is a dangerous thing;

2 Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

3 There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

4 And drinking largely sobers us again.

5 Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts,

6 In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts,

7 While from the bounded level of our mind,

8 Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

9 But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise

10 New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

11 So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try,

12 Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky;

13 The eternal snows appear already past,

14 And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

15 But those attained, we tremble to survey

16 The growing labours of the lengthened way,

17 The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes,

18 Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Summary

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” themes.

Shallow Learning vs. Deep Understanding

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

A little learning is a dangerous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring: There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain, And drinking largely sobers us again.

Fired at first sight with what the Muse imparts, In fearless youth we tempt the heights of Arts, While from the bounded level of our mind, Short views we take, nor see the lengths behind,

But, more advanced, behold with strange surprise New, distant scenes of endless science rise!

Lines 11-14

So pleased at first, the towering Alps we try, Mount o'er the vales, and seem to tread the sky; The eternal snows appear already past, And the first clouds and mountains seem the last;

Lines 15-18

But those attained, we tremble to survey The growing labours of the lengthened way, The increasing prospect tires our wandering eyes, Hills peep o'er hills, and Alps on Alps arise!

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Symbols

The Mountains/Alps

- See where this symbol appears in the poem.

“From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

Extended Metaphor

“from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- A little learning

- Pierian spring

- Bounded level

- Short views

- The lengthened way

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “From An Essay on Criticism: A little learning is a dangerous thing”

Rhyme scheme, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” speaker, “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” setting, literary and historical context of “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing”, more “from an essay on criticism: a little learning is a dangerous thing” resources, external resources.

The Poem Aloud — Listen to an audiobook of Pope's "Essay on Criticism" (the "A little learning" passage starts at 12:57).

The Poet's Life — Read a biography of Alexander Pope at the Poetry Foundation.

"Alexander Pope: Rediscovering a Genius" — Watch a BBC documentary on Alexander Pope.

More on Pope's Life — A summary of Pope's life and work at Poets.org.

Pope at the British Library — More resources and articles on the poet.

LitCharts on Other Poems by Alexander Pope

Ode on Solitude

Ask LitCharts AI: The answer to your questions

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism

Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 8, 2020 • ( 1 )

An Essay on Criticism (1711) was Pope’s first independent work, published anonymously through an obscure bookseller [12–13]. Its implicit claim to authority is not based on a lifetime’s creative work or a prestigious commission but, riskily, on the skill and argument of the poem alone. It offers a sort of master-class not only in doing criticism but in being a critic:addressed to those – it could be anyone – who would rise above scandal,envy, politics and pride to true judgement, it leads the reader through a qualifying course. At the end, one does not become a professional critic –the association with hired writing would have been a contaminating one for Pope – but an educated judge of important critical matters.

But, of the two, less dang’rous is th’ Offence, To tire our Patience, than mislead our Sense: Some few in that, but Numbers err in this, Ten Censure wrong for one who Writes amiss; A Fool might once himself alone expose, Now One in Verse makes many more in Prose.

The simple opposition we began with develops into a more complex suggestion that more unqualified people are likely to set up for critic than for poet, and that such a proliferation is serious. Pope’s typographically-emphasised oppositions between poetry and criticism, verse and prose,patience and sense, develop through the passage into a wider account of the problem than first proposed: the even-handed balance of the couplets extends beyond a simple contrast. Nonetheless, though Pope’s oppositions divide, they also keep within a single framework different categories of writing: Pope often seems to be addressing poets as much as critics. The critical function may well depend on a poetic function: this is after all an essay on criticism delivered in verse, and thus acting also as poetry and offering itself for criticism. Its blurring of categories which might otherwise be seen as fundamentally distinct, and its often slippery transitions from area to area, are part of the poem’s comprehensive,educative character.

Literary Criticism of Alexander Pope

Addison, who considered the poem ‘a Master-piece’, declared that its tone was conversational and its lack of order was not problematic: ‘The Observations follow one another like those in Horace’s Art of Poetry, without that Methodical Regularity which would have been requisite in a Prose Author’ (Barnard 1973: 78). Pope, however, decided during the revision of the work for the 1736 Works to divide the poem into three sections, with numbered sub-sections summarizing each segment of argument. This impluse towards order is itself illustrative of tensions between creative and critical faculties, an apparent casualness of expression being given rigour by a prose skeleton. The three sections are not equally balanced, but offer something like the thesis, antithesis, and synthesis of logical argumentation – something which exceeds the positive-negative opposition suggested by the couplet format. The first section (1–200) establishes the basic possibilities for critical judgement;the second (201–559) elaborates the factors which hinder such judgement;and the third (560–744) celebrates the elements which make up true critical behaviour.

Part One seems to begin by setting poetic genius and critical taste against each other, while at the same time limiting the operation of teaching to those ‘who have written well ’ ( EC, 11–18). The poem immediately stakes an implicit claim for the poet to be included in the category of those who can ‘write well’ by providing a flamboyant example of poetic skill in the increasingly satiric portrayal of the process by which failed writers become critics: ‘Each burns alike, who can, or cannot write,/Or with a Rival’s, or an Eunuch ’s spite’ ( EC, 29–30). At the bottom of the heap are ‘half-learn’d Witlings, num’rous in our Isle’, pictured as insects in an early example of Pope’s favourite image of teeming, writerly promiscuity (36–45). Pope then turns his attention back to the reader,conspicuously differentiated from this satiric extreme: ‘ you who seek to give and merit Fame’ (the combination of giving and meriting reputation again links criticism with creativity). The would-be critic, thus selected, is advised to criticise himself first of all, examining his limits and talents and keeping to the bounds of what he knows (46-67); this leads him to the most major of Pope’s abstract quantities within the poem (and within his thought in general): Nature.

First follow NATURE, and your Judgment frame By her just Standard, which is still the same: Unerring Nature, still divinely bright, One clear, unchang’d, and Universal Light, Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart, At once the Source, and End, and Te s t of Art.

( EC, 68–73)

Dennis complained that Pope should have specified ‘what he means by Nature, and what it is to write or to judge according to Nature’ ( TE I: 219),and modern analyses have the burden of Romantic deifications of Nature to discard: Pope’s Nature is certainly not some pantheistic, powerful nurturer, located outside social settings, as it would be for Wordsworth,though like the later poets Pope always characterises Nature as female,something to be quested for by male poets [172]. Nature would include all aspects of the created world, including the non-human, physical world, but the advice on following Nature immediately follows the advice to study one’s own internal ‘Nature’, and thus means something like an instinctively-recognised principle of ordering, derived from the original,timeless, cosmic ordering of God (the language of the lines implicitly aligns Nature with God; those that follow explicitly align it with the soul). Art should be derived from Nature, should seek to replicate Nature, and can be tested against the unaltering standard of Nature, which thus includes Reason and Truth as reflections of the mind of the original poet-creator, God.

In a fallen universe, however, apprehension of Nature requires assistance: internal gifts alone do not suffice.

Some, to whom Heav’n in Wit has been profuse, Want as much more, to turn it to its use; For Wit and Judgment often are at strife, Tho’ meant each other’s Aid, like Man and Wife.

( EC, 80–03)

Wit, the second of Pope’s abstract qualities, is here seamlessly conjoined with the discussion of Nature: for Pope, Wit means not merely quick verbal humour but something almost as important as Nature – a power of invention and perception not very different from what we would mean by intelligence or imagination. Early critics again seized on the first version of these lines (which Pope eventually altered to the reading given here) as evidence of Pope’s inability to make proper distinctions: he seems to suggest that a supply of Wit sometimes needs more Wit to manage it, and then goes on to replace this conundrum with a more familiar opposition between Wit (invention) and Judgment (correction). But Pope stood by the essential point that Wit itself could be a form of Judgment and insisted that though the marriage between these qualities might be strained, no divorce was possible.

Nonetheless, some external prop to Wit was necessary, and Pope finds this in those ‘RULES’ of criticism derived from Nature:

Those RULES of old discover’d, not devis’d, Are Nature still, but Nature Methodiz’d; Nature, like Liberty , is but restrain’d By the same Laws which first herself ordain’d.

( EC, 88–91)

Nature, as Godlike principle of order, is ‘discover’d’ to operate according to certain principles stated in critical treatises such as Aristotle’s Poetics or Horace’s Ars Poetica (or Pope’s Essay on Criticism ). In the golden age of Greece (92–103), Criticism identified these Rules of Nature in early poetry and taught their use to aspiring poets. Pope contrasts this with the activities of critics in the modern world, where often criticism is actively hostile to poetry, or has become an end in itself (114–17). Right judgement must separate itself out from such blind alleys by reading Homer: ‘ You then whose Judgment the right Course would steer’ ( EC, 118) can see yourself in the fable of ‘young Maro ’ (Virgil), who is pictured discovering to his amazement the perfect original equivalence between Homer, Nature, and the Rules (130–40). Virgil the poet becomes a sort of critical commentary on the original source poet of Western literature,Homer. With assurance bordering consciously on hyperbole, Pope can instruct us: ‘Learn hence for Ancient Rules a just Esteem;/To copy Nature is to copy Them ’ ( EC, 139–40).

Despite the potential for neat conclusion here, Pope has a rider to offer,and again it is one which could be addressed to poet or critic: ‘Some Beauties yet, no Precepts can declare,/For there’s a Happiness as well as Care ’ ( EC, 141–2). As well as the prescriptions of Aristotelian poetics,Pope draws on the ancient treatise ascribed to Longinus and known as On the Sublime [12]. Celebrating imaginative ‘flights’ rather than representation of nature, Longinus figures in Pope’s poem as a sort of paradox:

Great Wits sometimes may gloriously offend, And rise to Faults true Criticks dare not mend; From vulgar Bounds with brave Disorder part, And snatch a Grace beyond the Reach of Art, Which, without passing thro’ the Judgment , gains The Heart, and all its End at once attains.

( EC, 152–7)

This occasional imaginative rapture, not predictable by rule, is an important concession, emphasised by careful typographic signalling of its paradoxical nature (‘ gloriously offend ’, and so on); but it is itself countered by the caution that ‘The Critick’ may ‘put his Laws in force’ if such licence is unjustifiably used. Pope here seems to align the ‘you’ in the audience with poet rather than critic, and in the final lines of the first section it is the classical ‘ Bards Triumphant ’ who remain unassailably immortal, leavingPope to pray for ‘some Spark of your Coelestial Fire’ ( EC, 195) to inspire his own efforts (as ‘The last, the meanest of your Sons’, EC, 196) to instruct criticism through poetry.

Following this ringing prayer for the possibility of reestablishing a critical art based on poetry, Part II (200-559) elaborates all the human psychological causes which inhibit such a project: pride, envy,sectarianism, a love of some favourite device at the expense of overall design. The ideal critic will reflect the creative mind, and will seek to understand the whole work rather than concentrate on minute infractions of critical laws:

A perfect Judge will read each Work of Wit With the same Spirit that its Author writ, Survey the Whole, nor seek slight Faults to find, Where Nature moves, and Rapture warms the Mind;

( EC, 233–6)

Most critics (and poets) err by having a fatal predisposition towards some partial aspect of poetry: ornament, conceit, style, or metre, which they use as an inflexible test of far more subtle creations. Pope aims for akind of poetry which is recognisable and accessible in its entirety:

True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest, What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest, Something, whose Truth convinc’d at Sight we find, That gives us back the Image of our Mind:

( EC, 296–300)

This is not to say that style alone will do, as Pope immediately makesplain (305–6): the music of poetry, the ornament of its ‘numbers’ or rhythm, is only worth having because ‘The Sound must seem an Eccho to the Sense ’ ( EC, 365). Pope performs and illustrates a series of poetic clichés – the use of open vowels, monosyllabic lines, and cheap rhymes:

Tho’ oft the Ear the open Vowels tire … ( EC , 345) And ten low Words oft creep in one dull Line … ( EC , 347) Where-e’er you find the cooling Western Breeze, In the next Line, it whispers thro’ the Trees … ( EC, 350–1)

These gaffes are contrasted with more positive kinds of imitative effect:

Soft is the Strain when Zephyr gently blows, And the smooth Stream in smoother Numbers flows; But when loud Surges lash the sounding Shore, The hoarse, rough Verse shou’d like the Torrent roar.

( EC, 366–9)

Again, this functions both as poetic instance and as critical test, working examples for both classes of writer.

After a long series of satiric vignettes of false critics, who merely parrot the popular opinion, or change their minds all the time, or flatter aristocratic versifiers, or criticise poets rather than poetry (384-473), Pope again switches attention to educated readers, encouraging (or cajoling)them towards staunchly independent and generous judgment within what is described as an increasingly fraught cultural context, threatened with decay and critical warfare (474–525). But, acknowledging that even‘Noble minds’ will have some ‘Dregs … of Spleen and sow’r Disdain’ ( EC ,526–7), Pope advises the critic to ‘Discharge that Rage on more ProvokingCrimes,/Nor fear a Dearth in these Flagitious Times’ (EC, 528–9): obscenity and blasphemy are unpardonable and offer a kind of lightning conductor for critics to purify their own wit against some demonised object of scorn.

If the first parts of An Essay on Criticism outline a positive classical past and troubled modern present, Part III seeks some sort of resolved position whereby the virtues of one age can be maintained during the squabbles of the other. The opening seeks to instill the correct behaviour in the critic –not merely rules for written criticism, but, so to speak, for enacted criticism, a sort of ‘ Good Breeding ’ (EC, 576) which politely enforces without seeming to enforce:

LEARN then what MORALS Criticks ought to show, For ’tis but half a Judge’s Task , to Know. ’Tis not enough, Taste, Judgment, Learning, join; In all you speak, let Truth and Candor shine … Be silent always when you doubt your Sense; And speak, tho’ sure , with seeming Diffidence …Men must be taught as if you taught them not; And Things unknown propos’d as Things forgot:

( EC , 560–3, 566–7, 574–5)

This ideally-poised man of social grace cannot be universally successful: some poets, as some critics, are incorrigible and it is part of Pope’s education of the poet-critic to leave them well alone. Synthesis, if that is being offered in this final part, does not consist of gathering all writers into one tidy fold but in a careful discrimination of true wit from irredeemable ‘dulness’ (584–630).

Thereafter, Pope has two things to say. One is to set a challenge to contemporary culture by asking ‘where’s the Man’ who can unite all necessary humane and intellectual qualifications for the critic ( EC, 631–42), and be a sort of walking oxymoron, ‘Modestly bold, and humanly severe’ in his judgements. The other is to insinuate an answer. Pope offers deft characterisations of critics from Aristotle to Pope who achieve the necessary independence from extreme positions: Aristotle’s primary treatise is likened to an imaginative voyage into the land of Homer which becomes the source of legislative power; Horace is the poetic model for friendly conversational advice; Quintilian is a useful store of ‘the justest Rules, and clearest Method join’d’; Longinus is inspired by the Muses,who ‘bless their Critick with a Poet’s Fire’ ( EC, 676). These pairs include and encapsulate all the precepts recommended in the body of the poem. But the empire of good sense, Pope reminds us, fell apart after the fall of Rome,leaving nothing but monkish superstition, until the scholar Erasmus,always Pope’s model of an ecumenical humanist, reformed continental scholarship (693-696). Renaissance Italy shows a revival of arts, including criticism; France, ‘a Nation born to serve’ ( EC , 713) fossilised critical and poetic practice into unbending rules; Britain, on the other hand, ‘ Foreign Laws despis’d,/And kept unconquer’d, and unciviliz’d’ ( EC, 715–16) – a deftly ironic modulation of what appears to be a patriotic celebration intosomething more muted. Pope does however cite two earlier verse essays (by John Sheffield, Duke of Buckinghamshire, and Wentworth Dillon, Earl of Roscommon) [13] before paying tribute to his own early critical mentor, William Walsh, who had died in 1708 [9]. Sheffield and Dillon were both poets who wrote criticism in verse, but Walsh was not a poet; in becoming the nearest modern embodiment of the ideal critic, his ‘poetic’ aspect becomes Pope himself, depicted as a mixture of moderated qualities which reminds us of the earlier ‘Where’s the man’ passage: he is quite possibly here,

Careless of Censure , nor too fond of Fame, Still pleas’d to praise, yet not afraid to blame, Averse alike to Flatter , or Offend, Not free from Faults, nor yet too vain to mend.

( EC , 741–44)

It is a kind of leading from the front, or tuition by example, as recommended and practised by the poem. From an apparently secondary,even negative, position (writing on criticism, which the poem sees as secondary to poetry), the poem ends up founding criticism on poetry, and deriving poetry from the (ideal) critic.

Early criticism celebrated the way the poem seemed to master and exemplify its own stated ideals, just as Pope had said of Longinus that he ‘Is himself that great Sublime he draws’ ( EC, 680). It is a poem profuse with images, comparisons and similes. Johnson thought the longest example,that simile comparing student’s progress in learning with a traveller’s journey in Alps was ‘perhaps the best that English poetry can shew’: ‘The simile of the Alps has no useless parts, yet affords a striking picture by itself: it makes the foregoing position better understood, and enables it to take faster hold on the attention; it assists the apprehension, and elevates the fancy’ (Johnson 1905: 229–30). Many of the abstract precepts aremade visible in this way: private judgment is like one’s reliance on one’s(slightly unreliable) watch (9– 10); wit and judgment are like man and wife(82–3); critics are like pharmacists trying to be doctors (108–11). Much ofthe imagery is military or political, indicating something of the social role(as legislator in the universal empire of poetry) the critic is expected toadopt; we are also reminded of the decay of empires, and the potentialdecay of cultures (there is something of The Dunciad in the poem). Muchof it is religious, as with the most famous phrases from the poem (‘For Fools rush in where angels fear to tread’; ‘To err is human, to forgive, divine’), indicating the level of seriousness which Pope accords the matterof poetry. Much of it is sexual: creativity is a kind of manliness, wooing Nature, or the Muse, to ‘generate’ poetic issue, and false criticism, likeobscenity, derives from a kind of inner ‘impotence’. Patterns of suchimagery can be harnessed to ‘organic’ readings of the poem’s wholeness. But part of the life of the poem, underlying its surface statements andmetaphors, is its continual shifts of focus, its reminders of that which liesoutside the tidying power of couplets, its continual reinvention of the ‘you’opposed to the ‘they’ of false criticism, its progressive displacement of theopposition you thought you were looking at with another one whichrequires your attention.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Atkins, G. Douglas (1986): Quests of Difference: Reading Pope’s Poems (Lexing-ton: Kentucky State University Press) Barnard, John, ed. (1973): Pope: The Critical Heritage (London and Boston:Routledge and Kegan Paul) Bateson, F.W. and Joukovsky, N.A., eds, (1971): Alexander Pope: A Critical Anthology (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books) Brower, Reuben (1959): Alexander Pope: The Poetry of Allusion (Oxford: Clarendon Press) Brown, Laura (1985): Alexander Pope (Oxford: Basil Blackwell) Davis, Herbert ed. (1966): Pope: Poetical Works (Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress Dixon, Peter, ed. (1972): Alexander Pope (London: G. Bell and Sons) Empson, William (1950): ‘Wit in the Essay on Criticism ’, Hudson Review, 2: 559–77 Erskine-Hill, Howard and Smith, Anne, eds (1979): The Art of Alexander Pope (London: Vision Press) Erskine-Hill, Howard (1982): ‘Alexander Pope: The Political Poet in his Time’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 15: 123–148 Fairer, David (1984): Pope’s Imagination (Manchester: Manchester University Press) Fairer, David, ed. (1990): Pope: New Contexts (Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf) Morris, David B. (1984): Alexander Pope: The Genius of Sense (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press) Nuttall, A.D. (1984): Pope’s ‘ Essay on Man’ (London: George Allen and Unwin) Rideout, Tania (1992): ‘The Reasoning Eye: Alexander Pope’s Typographic Vi-sion in the Essay on Man’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 55:249–62 Rogers, Pat (1993a): Alexander Pope (Oxford: Oxford University Press) Rogers, Pat (1993b): Essay s on Pope (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) Savage, Roger (1988) ‘Antiquity as Nature: Pope’s Fable of “Young Maro”’, in An Essay on Criticism, in Nicholson (1988), 83–116 Schmitz, R. M. (1962): Pope’s Essay on Criticism 1709: A Study of the BodleianMS Text, with Facsimiles, Transcripts and Variants (St Louis: Washington University Press) Warren, Austin (1929): Alexander Pope as Critic and Humanist (Princeton: PrincetonUniversity Press) Woodman, Thomas (1989): Politeness and Poetry in the Age of Pope (Rutherford,New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press)

Share this:

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Alexander Pope , Alexander Pope An Essay on Criticism , Alexander Pope as a Neoclassical Poet , Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , An Essay on Criticism , An Essay on Criticism as a Neoclassical Poem , Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Analysis of An Essay on Criticism , Bibliography of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Bibliography of An Essay on Criticism , Character Study of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Character Study of An Essay on Criticism , Criticism of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Criticism of An Essay on Criticism , English Literature , Essays of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Essays of An Essay on Criticism , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Neoclassical Poetry , Neoclassicism in Poetry , Notes of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Notes of An Essay on Criticism , Plot of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Plot of An Essay on Criticism , Poetry , Simple Analysis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Simple Analysis of An Essay on Criticism , Study Guides of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Study Guides of An Essay on Criticism , Summary of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Summary of An Essay on Criticism , Synopsis of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Synopsis of An Essay on Criticism , Themes of Alexander Pope’s An Essay on Criticism , Themes of An Essay on Criticism

Related Articles

- Analysis of Alexander Pope's An Essay on Man | Literary Theory and Criticism

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Humanities ›

- English Grammar ›

How to Write a Critical Essay

Hill Street Studios / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

Olivia Valdes was the Associate Editorial Director for ThoughtCo. She worked with Dotdash Meredith from 2017 to 2021.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Olivia-Valdes_WEB1-1e405fc799d9474e9212215c4f21b141.jpg)

- B.A., American Studies, Yale University

A critical essay is a form of academic writing that analyzes, interprets, and/or evaluates a text. In a critical essay, an author makes a claim about how particular ideas or themes are conveyed in a text, then supports that claim with evidence from primary and/or secondary sources.

In casual conversation, we often associate the word "critical" with a negative perspective. However, in the context of a critical essay, the word "critical" simply means discerning and analytical. Critical essays analyze and evaluate the meaning and significance of a text, rather than making a judgment about its content or quality.

What Makes an Essay "Critical"?

Imagine you've just watched the movie "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory." If you were chatting with friends in the movie theater lobby, you might say something like, "Charlie was so lucky to find a Golden Ticket. That ticket changed his life." A friend might reply, "Yeah, but Willy Wonka shouldn't have let those raucous kids into his chocolate factory in the first place. They caused a big mess."

These comments make for an enjoyable conversation, but they do not belong in a critical essay. Why? Because they respond to (and pass judgment on) the raw content of the movie, rather than analyzing its themes or how the director conveyed those themes.

On the other hand, a critical essay about "Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory" might take the following topic as its thesis: "In 'Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,' director Mel Stuart intertwines money and morality through his depiction of children: the angelic appearance of Charlie Bucket, a good-hearted boy of modest means, is sharply contrasted against the physically grotesque portrayal of the wealthy, and thus immoral, children."

This thesis includes a claim about the themes of the film, what the director seems to be saying about those themes, and what techniques the director employs in order to communicate his message. In addition, this thesis is both supportable and disputable using evidence from the film itself, which means it's a strong central argument for a critical essay .

Characteristics of a Critical Essay

Critical essays are written across many academic disciplines and can have wide-ranging textual subjects: films, novels, poetry, video games, visual art, and more. However, despite their diverse subject matter, all critical essays share the following characteristics.

- Central claim . All critical essays contain a central claim about the text. This argument is typically expressed at the beginning of the essay in a thesis statement , then supported with evidence in each body paragraph. Some critical essays bolster their argument even further by including potential counterarguments, then using evidence to dispute them.

- Evidence . The central claim of a critical essay must be supported by evidence. In many critical essays, most of the evidence comes in the form of textual support: particular details from the text (dialogue, descriptions, word choice, structure, imagery, et cetera) that bolster the argument. Critical essays may also include evidence from secondary sources, often scholarly works that support or strengthen the main argument.

- Conclusion . After making a claim and supporting it with evidence, critical essays offer a succinct conclusion. The conclusion summarizes the trajectory of the essay's argument and emphasizes the essays' most important insights.

Tips for Writing a Critical Essay

Writing a critical essay requires rigorous analysis and a meticulous argument-building process. If you're struggling with a critical essay assignment, these tips will help you get started.

- Practice active reading strategies . These strategies for staying focused and retaining information will help you identify specific details in the text that will serve as evidence for your main argument. Active reading is an essential skill, especially if you're writing a critical essay for a literature class.

- Read example essays . If you're unfamiliar with critical essays as a form, writing one is going to be extremely challenging. Before you dive into the writing process, read a variety of published critical essays, paying careful attention to their structure and writing style. (As always, remember that paraphrasing an author's ideas without proper attribution is a form of plagiarism .)

- Resist the urge to summarize . Critical essays should consist of your own analysis and interpretation of a text, not a summary of the text in general. If you find yourself writing lengthy plot or character descriptions, pause and consider whether these summaries are in the service of your main argument or whether they are simply taking up space.

- Critical Analysis in Composition

- Writing About Literature: Ten Sample Topics for Comparison & Contrast Essays

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- A Critical Analysis of George Orwell's 'A Hanging'

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- literary present (verbs)

- Book Report: Definition, Guidelines, and Advice

- personal statement (essay)

- Definition Examples of Collage Essays

- Definition and Examples of Evaluation Essays

- Composition Type: Problem-Solution Essays

- What Is Plagiarism?

- The Power and Pleasure of Metaphor

- Quotes About Close Reading

- What Is a Compelling Introduction?

Writing Critiques

Writing a critique involves more than pointing out mistakes. It involves conducting a systematic analysis of a scholarly article or book and then writing a fair and reasonable description of its strengths and weaknesses. Several scholarly journals have published guides for critiquing other people’s work in their academic area. Search for a “manuscript reviewer guide” in your own discipline to guide your analysis of the content. Use this handout as an orientation to the audience and purpose of different types of critiques and to the linguistic strategies appropriate to all of them.

Types of critique

Article or book review assignment in an academic class.

Text: Article or book that has already been published Audience: Professors Purpose:

- to demonstrate your skills for close reading and analysis

- to show that you understand key concepts in your field

- to learn how to review a manuscript for your future professional work

Published book review

Text: Book that has already been published Audience: Disciplinary colleagues Purpose:

- to describe the book’s contents

- to summarize the book’s strengths and weaknesses

- to provide a reliable recommendation to read (or not read) the book

Manuscript review

Text: Manuscript that has been submitted but has not been published yet Audience: Journal editor and manuscript authors Purpose:

- to provide the editor with an evaluation of the manuscript

- to recommend to the editor that the article be published, revised, or rejected

- to provide the authors with constructive feedback and reasonable suggestions for revision

Language strategies for critiquing

For each type of critique, it’s important to state your praise, criticism, and suggestions politely, but with the appropriate level of strength. The following language structures should help you achieve this challenging task.

Offering Praise and Criticism

A strategy called “hedging” will help you express praise or criticism with varying levels of strength. It will also help you express varying levels of certainty in your own assertions. Grammatical structures used for hedging include:

Modal verbs Using modal verbs (could, can, may, might, etc.) allows you to soften an absolute statement. Compare:

This text is inappropriate for graduate students who are new to the field. This text may be inappropriate for graduate students who are new to the field.

Qualifying adjectives and adverbs Using qualifying adjectives and adverbs (possible, likely, possibly, somewhat, etc.) allows you to introduce a level of probability into your comments. Compare:

Readers will find the theoretical model difficult to understand. Some readers will find the theoretical model difficult to understand. Some readers will probably find the theoretical model somewhat difficult to understand completely.

Note: You can see from the last example that too many qualifiers makes the idea sound undesirably weak.

Tentative verbs Using tentative verbs (seems, indicates, suggests, etc.) also allows you to soften an absolute statement. Compare:

This omission shows that the authors are not aware of the current literature. This omission indicates that the authors are not aware of the current literature. This omission seems to suggest that the authors are not aware of the current literature.

Offering suggestions

Whether you are critiquing a published or unpublished text, you are expected to point out problems and suggest solutions. If you are critiquing an unpublished manuscript, the author can use your suggestions to revise. Your suggestions have the potential to become real actions. If you are critiquing a published text, the author cannot revise, so your suggestions are purely hypothetical. These two situations require slightly different grammar.

Unpublished manuscripts: “would be X if they did Y” Reviewers commonly point out weakness by pointing toward improvement. For instance, if the problem is “unclear methodology,” reviewers may write that “the methodology would be more clear if …” plus a suggestion. If the author can use the suggestions to revise, the grammar is “X would be better if the authors did Y” (would be + simple past suggestion).

The tables would be clearer if the authors highlighted the key results. The discussion would be more persuasive if the authors accounted for the discrepancies in the data.

Published manuscripts: “would have been X if they had done Y” If the authors cannot revise based on your suggestions, use the past unreal conditional form “X would have been better if the authors had done Y” (would have been + past perfect suggestion).

The tables would have been clearer if the authors had highlighted key results. The discussion would have been more persuasive if the authors had accounted for discrepancies in the data.

Note: For more information on conditional structures, see our Conditionals handout .

Make a Gift

23 Constructive Criticism Examples

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Constructive criticism refers to providing feedback to a person or group that is delivered in a positive tone with the intent of helping others improve.

Examples of constructive criticism include the sandwich method of feedback, using the 3×3 method, and ensuring you provide genuine suggestions for improvement.

The distinguishing characteristic of constructive criticism is that:

- The goal is to provide support for growth.

- You avoid damaging a person’s self-esteem.

Constructive Criticism Definition

Constructive criticism is honest, genuine, well-meaning feedback that provides a critique of the strengths and weaknesses of something or someone.

The criticism should be specific and offers clear suggestions on how to address deficiencies. Remarks should are clear and the suggestions provided should be feasible and reasonable.

Professionals working in a management capacity need to be masters of delivering constructive criticism.

As Nash et al. (2018) point out:

“In almost any profession or pastime—from education, to business, to sports and the performing arts—being able to improve our skills can hinge on receiving good quality feedback from others.” (Nash et al., 2018, p. 1864)

Constructive Criticism Examples

1. being specific in your feedback.

To ensure your feedback is constructive , focus on specific actions or behaviors that could be improved. If you fall into the trap of making generalized statements or personal attacks, the criticism stops being constructive because there’s no clear path for improvement.

Examples could be:

- “At the five-minute mark of your presentation, you stopped making eye contact with the audience.”

- “The problem with your golf swing is your hip placement. If you square your hips, you may find more success.”

- “The third paragraph of the essay is where it goes off track. I would recommend re-writing that paragraph to make sure it clearly links to the previous paragraph.”

2. Using “I” Statements

The use of “I” statements tends to help frame critique more gently. “You” statements, on the other hand, tend to come across as aggressive and accusational. Expressing your feelings and observations allows room for discussion rather than conflict.

- “I feel like you interrupted me during my presentation and it led to a less productive meeting. Can we implement a strategy for minimizing interruptions in the next meeting?”

- “I liked what you said, but I wonder if you’d consider making a quick change to improve your output. Would you like to discuss it?”

3. Offering Suggestions for Improvement

If you simply criticize, you’re not being constructive . Rather, you’re being destructive. To be constructive, you need to think up ways to build the person up. After all, constructive comes from the concept of “to build”.

- “Great job at the beginning, but in the middle of your presentation your voice started getting soft. Can I suggest you focus on maintaining voice projection throughout the presentation next time?”

- “I have written down three ideas for improvement of your essay. First, make sure you provide references to academic sources in each paragraph. Second, I’d suggest you write a conclusion that sums up your arguments. Third, make sure you edit your work before submitting to remove spelling errors.”

4. Encouraging Open Communication during Criticism

People who offer constructive criticism aren’t there just to criticize then walk away. They want to help the person improve. So, it’s important for you to let the person ask questions or give responses so you can engage in communication.

- “Okay, I will tell you what it looked like you did from my perspective and then can you tell me if you agree?”

- “I’m going to make a few suggestions then after that can you let me know how you feel about implementing the changes I suggest?”

5. Offering Opportunities for Growth

You might be noticing a theme: constructive criticism is always about helping someone get better. It’s not about cutting them down or making you feel good about being better than someone else. So, reflect on your criticism and have a think about whether it’s provided the person with opportunities to grow.

- “I think there’s potential for improvement here. Let’s talk about some steps you can take so you do better next time.”

- “This wasn’t your best work, so let’s go back to basics and talk about getting those fundamentals right again.”

6. Providing Praise along with Criticism

If all you do is give negative feedback, the person you’re giving the feedback to is going to feel deflated. So, good constructive criticism looks at both the positives and areas for improvement so the person feels you’re not there to bring them down, but there to help.

- “I found 2 things I felt you did really well and 2 that you could improve on. Let’s start with the strengths.”

- “You did a great job with your tone of voice in the presentation, but the subject matter needs a bit of work. If you can improve on the subject matter, your presentation could end up really strong.”

- “I really appreciate that you had the courage to give this a go. I have some feedback for you that will make next time you try even better.”

7. choosing an Appropriate Time and Place

Make sure your feedback is given in a context that won’t embarrass the person or make them feel confronted. For example, you could try to give the constructive criticism in private. Or, you might want to take a break between the task and the feedback to make sure the person is relaxed and has some objective space.

- A professor asks a student to stay back after class to give the constructive criticism rather than doing it in front of the rest of the class.

- A wife is frustrated at her husband, but doesn’t express it in front of the kids. Instead, she waits until they’re in bed that night and having a debrief to gently discuss the issue.

8. Maintaining a positive and supportive tone

Anger, sarcasm, or condescension have no place in constructive criticism. This is because aggressive tones and postures are not constructive . Rather, they will lead to conflict.

- Harry is really angry that John said something offensive. But instead of yelling or retaliating in anger, he stops, takes a breathe, and uses an “I” statement to express his feelings.

- A teacher is frustrated at a misbehaving student, but she puts on a big smile and says “Sam, I know you’re better than that! Remember last week when you sat politely through the class presentations? I know you can do that again this week.”

9. Focusing on the Behavior Rather than a Person’s Character

Personal attacks or criticisms of a person’s core character are not conducive to positive feedback . Constructive criticism focuses on the task or behavior that needs to be improved upon, not on the person themself. This is fundamental to the concept of unconditional positive regard .

- “Okay, let’s talk about the task at hand and push other things out of the conversation for now. I believe you can improve on the task with a few simple steps.”

- “This assessment task wasn’t done to the best of your ability. I know you have the right growth mindset to see some improvements, so let’s talk about some ways to improve your work.”

10. Following up on your Feedback

Constructive criticism is supportive. One of the best ways to be supportive is to let the person receiving the feedback to know you’re there to help them through the process of improving. To do this, tell them you’ll follow-up, then actually do it.

- “Now that we’ve talked about three ways to improve, let’s put in place a timeline. Could you suggest one thing you could do this week before our meeting again next Monday?”

- “Hey Tracy, I’m just following up on the feedback I gave the other day. Did you have any more thoughts about those weaknesses we discussed?”

- “Okay, let’s focus on the first step for improvement and push the other two aside for now. Could you drop me an email once you’ve fixed the first issue we discussed so I can give you some feedback on the improvements?”

Strategies for Providing Constructive Criticism

1. the 3×3 method.

One key to providing effective constructive criticism is to not overwhelm the recipient. Instead of listing all 17 things you saw wrong in their report, it is better to prioritize the feedback and narrow that list. It is much easier for a person to remember 3 key points than a long list.

The 3×3 method takes this basic principle one step further by recommending highlighting 3 strengths and the 3 ways that each of those strengths could have worked better.

For example, highlighting the organization of the presentation, and then following up with suggesting that it could have had greater impact if delivered with better intonation and emotional appeal.

The first half of the statement is positive, and accurate, and the second half offers a suggestion to make the first element even better.

Limiting this to a total of 3 statements gives the employee something to focus on, as opposed to them trying to do too much.

2. The STAR Method

The STAR method identifies 4 main components that each feedback session should include. The acronym stands for: Situation, Task, Action, and Result.

This method is effective because it is clear, specific, and offers a feasible suggestion on how the employee can improve the situation. The systematic nature of the process takes some of the negative emotional impacts out of delivering bad news.

Here is a breakdown of each component.

Situation/Task: the supervisor describes the situation or task being evaluated

Action: the supervisor then describes the action, specifically, either positive or negative, the employee displayed

Result: the employee then hears an explanation of the consequences of those actions so they understand fully

If the actions were negative, then a follow-up statement regarding how the employee can improve should be explained. Of course, being specific and reasonable is helpful.

3. The “No Feedback” Approach to Providing Feedback

When a supervisor is working with staff that are responsible and motivated, it is much easier to offer suggestions on how to improve. Because the personnel are professional, their priority is to improve and help the organization prosper.

In this scenario, it may not be necessary for those in a leadership position to deliver any criticism at all. Experienced professionals, that take their responsibilities seriously, tend to be reflective and self-critical.

Therefore, sometimes the best approach to delivering feedback is to not take the first step. For example, a supervisor can simply start the performance evaluation meeting by asking the employee to identify their strengths and weaknesses.

What follows can be quite enlightening. In fact, the employee may be more cognizant of their own shortcomings than what an observant supervisor is able to identify.

4. Use Reflective Questioning

Teachers deliver feedback to students on a routine basis. For instance, teachers make brief comments as they walk around the classroom monitoring students’ progress.

The results of quizzes, exams, term papers and oral presentations are graded and often include evaluative statements. Ideally, teachers can present that feedback in a constructive manner.

Teachers can deliver effective feedback by considering three reflective questions:

1. Where is the learner going?

Both teacher and student need to have a clear understanding of the learning goals and make sure they are achievable and challenging.

2. Where is the learner right now?

Student progress should be assessed and carefully tracked in relation to goals so that both teacher and student know the current situation.

3. How does the learner get there?

The teacher should be specific about the steps the student needs to take to accomplish the learning goals.

As Black and Wiliam argue:

“Feedback to any pupil should be about the particular qualities of his or her work, with advice on what he or she can do to improve, and should avoid comparisons with other pupils” (Black and Wiliam, 1998, p. 143).

Constructive criticism is a way of communicating to students and staff that takes a positive tone when identifying ways to improve. The goal is to facilitate growth so the individual has a greater chance of achieving success.

There are several structured techniques that can be applied in a feedback situation. Most have several common characteristics. For instance, starting out by identifying the individual’s strengths helps establish positive rapport.

This is followed by identifying specific errors, being sure to not use personal statements or strong language.

The path to success will point to specific actions that can produce better outcomes. It is important that those suggestions are reasonable and suitable for the individual receiving the feedback.

Constructive criticism can foster a positive environment and encourage continued effort towards improvement.

AbdulAzeem, A., & Elnibras, M. (2017). The criteria of constructive feedback: The feedback that counts. Journal of Health Specialties, 5 , 45-48.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards through Classroom Assessment. The Phi Delta Kappan, 80 (2), pp. 139-144, 146-148.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2005). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment . Granada Learning.

Fong, C., Warner, J., Williams, K., Schallert, D., Chen, L., Williamson, Z., & Lin, S. (2016). Deconstructing constructive criticism: The nature of academic emotions associated with constructive, positive, and negative feedback. Learning and Individual Differences, 49 , 393-399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.05.019

Lashley, F.R., & de Meneses, M. (2001). Student civility in nursing programs: a national survey. Journal of Professional Nursing: Official Journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 17(2) , 81-86.

Luparell, S. (2005). Why and how we should address student incivility in nursing programs. Annual Review of Nursing Education , 3 (2015), 23-36.

Nash, R. A., Winstone, N. E., Gregory, S. E. A., & Papps, E. (2018). A memory advantage for past-oriented over future-oriented performance feedback. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 44 (12), 1864–1879. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000549

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Niederriter, J. E., Eyth, D., & Thoman, J. (2017). Nursing students’ perceptions on characteristics of an effective clinical instructor. SAGE Open Nursing , 3 , 2377960816685571.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Write, learn, make friends, meet beta readers, and become the best writer you can be!

Join our writing group!

Critique vs. Criticism: How to Write a Good Critique, with Examples

by Daniel Rodrigues-Martin

Understanding critique vs. criticism

We all assign merit to the information we experience daily. We “judge” what we hear on the news. We “evaluate” a university lecture. We “like” or “dislike” a movie, a meal, a photo, a story. We’re all critics.

Some writer-readers struggle with this point, especially if they are young to writing and editing. Sitting in a judgment of another writer’s work often feels distasteful, and doing so may conjure negative memories of when we were misunderstood or dismissed by others.

Conversely, we might be willing to share our opinions with other writers while struggling with our competence. We can’t seem to say anything constructive. If we’re critiquing on Scribophile, we may feel that we are wasting one of the author’s coveted “spotlight” critiques.

Having used Scribophile on-and-off since 2009, I’ve seen countless readers qualify their commentary on my own work (“I don’t read your genre,” “I haven’t read your previous chapters,” “I’m not good with grammar,” etc.) and I’ve seen even more cry woe on the forums about how they can’t critique because they’re not experienced enough, not educated enough, or not talented enough. Others decry the very sort of criticism writers’ groups and workshop sites like Scribophile foster, suggesting that the perfunctory nature of such criticism is ultimately more harmful than helpful.

Scribophile as a community thrives on the principle of serious commitment to serious writing, and the foundation of that commitment is reading and responding to others’ work. If you want to explore some elements helpful to improving your critiquing skills, I invite you to get yourself some hot caffeine, strap on your thinking cap, and read on.

How to write a great critique in 3 steps

Listed here are some ideas I’ve found helpful for approaching others’ work; these tips are about your mindset as a critic. These ideas are by no means exhaustive. The best teacher is experience, and I encourage all writers to reflect on the ways in which they approach others’ work as well as how they can best contribute to the growth of others on and off of Scribophile.

1. If you’re genuine, you’ll be constructive

Being constructive means coming to the critique with the ultimate goal of helping the writer improve. It means always criticizing with good intentions for the writer. It does not equate to coddling—being so nice you’ll never say a hard thing—nor does it equate to browbeating—being so hard you’ll never say a nice thing.

Being dishonest or refusing to offer valid criticism where you’re able is a disservice to the writer. Don’t shy away from honesty. Few things are more constructive than hard truths delivered by critics who genuinely want to help and who tailor their criticism with an attitude of genuine interest.

As you interact with works on Scribophile or elsewhere, remember to always approach the task of criticism with a desire to be genuinely helpful. If your criticism is built on this foundation, your commentary will be constructive regardless of your competence and experience.

2. No jerks

As for literary criticism in general: I have long felt that any reviewer who expresses rage and loathing for a novel or a play or a poem is preposterous. He or she is like a person who has put on full armor and attacked a hot fudge sundae or a banana split. —Kurt Vonnegut

Few things will more quickly deflate a writer than unnecessarily harsh criticism. Being honest and being brutal are not the same thing. Critics must learn to express hard truths without coddling and without being jerks.

Even rude people can be good writers with valuable insights into the craft. The problem is that if you express valid insights obnoxiously, the author won’t care. In order for people to listen, they must feel that the person criticizing them has their best interest in mind, and being harsh doesn’t communicate your best interest.

In my earliest days writing, I received some negative criticism from a writer who decided to berate me for penning a bad phrase rather than explaining to me why the phrase didn’t work. Because he was rude, I insulated myself to his criticism. Years later, I reviewed the work and realized his criticism was valid. The problem was not the content of his criticism, but its malicious delivery. Had he come to my work with the desire to be genuinely helpful, I would have listened to what he had to say, and I might even have gained some enlightenment during a formative time in my writing career. The critic did me doubly wrong not only by being obnoxious, but by retarding my growth as a writer.

Unnecessarily harsh criticism is a sign of literary and personal immaturity. Don’t be a jerk.

3. Don’t be too timid

Flattering friends corrupt. —St. Augustine

Every writer likes to be praised, especially by those not obligated to praise them due to marital status or having given birth to them. But depthless praise can be just as damaging as heartless criticism. The reason for this is that it offers no real commentary on the work.

Refusing to offer criticism where it’s needed is one of the greatest disservices you as a critic can do for other writers. Some critics may fret that their criticism might be too discouraging if fully disclosed. Critics must contend with the reality that writing is art, people have opinions about art, and those opinions are not always going to be eruptions of praise. There is no safer environment to honestly and succinctly point out problem areas in a piece of writing than a forum designed for that very purpose.

None of this is to say that you shouldn’t commend a piece of work if it truly is fantastic or that you should not highlight the gems within a work. Again: constructive criticism is honest criticism. If a work is so well-crafted in your eyes that nothing worse than grammatical hiccups are present, tell the writer. They deserve to know they’ve done a fine job. Sometimes people genuinely deserve a “well done.” Don’t skimp on encouragement where it can be authentically offered. Even if a piece is messy, do your best to find a few strong points to highlight. It will express your best interest—especially if you had a lot of hard things to say.

The difference between a critique vs. criticism is whether it’s constructive

Be constructive , meaning, have the best intentions for helping the writer. This may mean telling hard truths. If hard truths must be told, do so respectfully. If praise is deserved, offer it. Highlight the strong points of a piece—even if they are far outweighed by the negative points. Be genuine in your motivations, and genuine action will follow.

Considering authorial intent while critique writing

This section concerns authorial intent and has as its purpose the critic’s growth as an interpreter of that intent. This section is not so much about judging an author’s intent as it’s about being aware of that intent and factoring that awareness into your commentary.

1. Context is king

It is important to appreciate the amount of subjectivity and pre-understanding all readers and listeners bring to the process of interpreting acts of human communication. But unless a speaker or author can retain the right to correct someone’s interpretation by saying ‘but that’s not what I meant’ or ‘that’s not even consistent with what I meant,’ all human communication will quickly break down. —Craig L. Blomberg

While interpreters are always within their rights to read whatever they want however they want to, what they are not at liberty to decide is authorial intent —what the author desired the audience to receive from their work.

As a reader and a critic, you must be careful to understand an author’s work on their own terms while also interpreting those words. There is a substantial difference between, “This is how I’m hearing what you’re saying,” and, “This is what I say your words mean.” Don’t presume to tell an author what their work is supposed to mean, but do tell them how you’re interpreting what they’ve written.

A work-in-progress can suffer from a variety of ailments. Contextual questions are not cut-and-dry like questions of syntax, grammar, or, to a degree, plotting. Questions of context have to do with the interaction of author intent and reader interpretation. They’re murky waters to navigate because you as the reader have to exercise a bit of telepathy; you have to try and get inside the author’s head, ultimately “What is the author trying to convey with this sentence, this piece? Who is this piece for, and will it successfully communicate with that target audience? Is it clear that there is a target audience?”

Some authors are great at genre pieces; they know all the chords to strike, they know what the tone of the piece should be, the kinds of characters who should appear. Other authors can completely muck it up. They’ll write a romance piece that reads like a technical manual or a flowery memoir with a tangle of dead-ending tangents. It’s not always easy and natural for new critics to explain why something does or doesn’t work, but innately, we know. When those moments come up, let the author know.

2. The unintended/unspoken

Asking the question, “Is that really what you meant?” isn’t always bad. All of us have been misunderstood. Sometimes the results are humorous, but other times, we’re grateful for the opportunity to correct misunderstandings.

If in your criticism you find yourself questioning the use of a word or phrase, or even of a character, idea, or plot point, it’s advisable to bring such questions to the writer’s attention. It may just be you, but it may not just be you. Unless the writer has a philosophical axe to grind, they probably mean to communicate clearly, and it should at least be made known that they may have botched it up.

Conversely, there are instances where things left unwritten speak volumes. Perhaps a character “falls off the radar” in mid-scene, and it leaves you scratching your head? It may be appropriate to point out confusing instances of the unwritten for the author’s consideration.

Because my own novel employs many neologisms, critics jumping in mid-story often highlight those neologisms to make sure I’m using them as intended. While it can get tedious to say to myself, “Yes, that is what it means,” I am always thankful for keen eyes. This is the kind of sharp, considerate criticism each of us should aim for and be thankful for if we receive it.

3. Accounting for genre and intended audience

A genre is “A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, marked by a distinctive style, form, or content.” When reading an author’s work, it’s crucial to take into account its genre and intended audience. If you’re even-handed in your critiquing, you’ll at some point be reading a story in a genre you might not otherwise touch, and while you might wish Twilight had been a one-off rather than a worldwide phenomenon, it’s inappropriate to harshly judge an author’s work simply because you don’t like their sort of story.

Consider the question of author intent and how that intent will resonate with an intended (or unintended!) audience. Sometimes, you must ignore whether or not a story resonates with you personally. Instead, ask yourself if it would resonate with your vampire-novel-loving daughter. Are the story, plot devices, characters, and verbiage appropriate for the intended audience? If yes, why or why not? If no, why or why not? Your personal tastes should not dictate the quality of your criticism. Train yourself to offer valuable insight even on writing you’d never pay money to read.

Remember these principles when reading work outside your sphere of interest. Being constructive doesn’t mean you have to love or even like the work. If something is written well, it’s written well—prejudices aside. If you’re truly unable to be objective, you would do the writer a better service by moving on.

4. Don’t pretend to be a non-writer

A film director watches other films differently than a moviegoer. A chef tastes a meal differently than the average person. As a writer, you necessarily see stories differently than non-writers. That’s not a bad thing.

We can be helpful to other writers by sharing our gut reactions no differently than an unversed beta reader. On the other hand, writers should be able to explain with more clarity than the average person why something does or doesn’t work in a story. A writer’s insight is of a different quality than a non-initiate’s insight. Both are needed for success, because if a writer one day moves on to pitch their work to those in the literary establishment, that work will not be judged by average readers until after it has survived the professional gauntlet.

All readers have the ability to share their gut reactions, but not all readers can slip on their “writer glasses” and offer critique on that level. Good critiques provide both types of insight, so as a fellow writer, bring your full experience to bear in helping others embarking on the same journey.

Understanding intent is part of a good critique

As best as you’re able, judge an author’s work on the basis of their intent—this includes noting instances of the unintended! In consideration of genre, judge the work not on the basis of your interest in the genre, but on the author’s skill at writing a piece that strikes the proper chords within the genre they’ve chosen. It’s not possible for you to read as a reader only, so don’t pretend to be something you’re not.

What makes a good critique?